Abstract

Modern facelift techniques utilize the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) to reposition facial fat from the anterior cheek into regions of lateral cheek and malar deflation, restoring the volumetric highlights noted in youth. In this chapter, we discuss the extended SMAS technique and methods to avoid inadvertent injury to the motor branches of the facial nerve.

7 Extended Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Technique

Key Points

Facial aging is due to intrinsic and extrinsic changes in skin, loss of ligamentous support, and volume deflation due to fat atrophy.

The extended superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) technique for facelifting repositions facial fat from the anterior cheek into regions of deflation in the lateral cheek and malar region, restoring the volumetric highlights noted in youth.

7.1 Preoperative Planning

7.1.1 Analysis

A comprehensive and systematic facial analysis is the most critical initial step in establishing goals and formulating a precise surgical plan for facial rejuvenation.

Areas of volume deflation are noted and marked preoperatively in the dependent position.

7.1.2 Standardized Photography and Digital Imaging

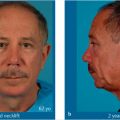

Standardized photographs including frontal, lateral, oblique, and basal views should be obtained for every patient.

Digital imaging is an excellent tool for communicating with the patient and evaluating patient’s expectations.

7.1.3 Managing Expectations

Review all photographic views with the patient.

It is extremely important to discuss with the patient what can and cannot be achieved with surgery.

7.2 Anatomy

7.2.1 Facial Soft Tissue Layers

From the superficial to the deep, the layers of the facial soft tissue are: (1) Skin, (2) subcutaneous fat, (3) superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), (4) mimetic muscle, (5) parotidomasseteric fascia (deep facial fascia), (6) plane of facial nerve, (7) parotid duct, and (8) buccal fat pad.

7.2.2 Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System

The SMAS represents a discrete fascial layer that separates the overlying subcutaneous fat from the underlying parotidomasseteric fascia (deep fascia) and facial nerve branches.

The SMAS represents a continuation of the superficial cervical fascia cephalad into the face; the corresponding deeper layer of cervical fascia (the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia) continues into the face and has been termed the parotidomasseteric fascia or deep facial fascia.

Within the cheek, the facial nerve branches, and the parotid duct, lie deep to the parotidomasseteric fascia after exiting the parotid. Therefore, when performing sub-SMAS dissection, if deep facial fascia is not violated, facial nerve injury will be prevented. The exceptions to this anatomic rule are along the lateral malar eminence and along the caudal masseter, both locations where facial nerve branches penetrate the deep fascia and lie within the plane between the SMAS and the deep fascia (see Staying Safe).

7.2.3 Retaining Ligaments

Zygomatic and mandibular ligaments are examples of osteocutaneous ligaments that originate from periosteum and insert directly into the dermis.

The masseteric cutaneous ligaments and parotid cutaneous ligaments are formed as a condensation between the superficial and deep fascia.

Attenuation of the retaining ligaments is responsible for many of the stigmata that occur with aging.

7.3 Staying Safe to Prevent Injury to the Facial Nerve during Subcutaneous Undermining

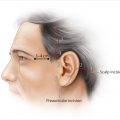

7.3.1 Frontal Branch

Must stay superficial to the temporoparietal fascia in the subcutaneous fat when dissecting inferior to superior.

The sentinel vein, noted when dissecting from the forehead toward the superior orbital rim, can be used as a landmark indicating proximity to the nerve while dissecting within the temporal region.

When using a lateral or superior approach, staying right on the superficial leaf of the deep temporal fascia is a safe plane of dissection.

7.3.2 Zygomatic and Buccal Branches

Be aware of the relative danger zones adjacent to retaining ligaments along the lateral malar eminence.

It is helpful to dissect both cephalad and caudal to the retaining ligaments to establish the proper plane of dissection superficial to the SMAS.

The zygomatic and upper masseteric retaining ligaments just lateral to the zygoma can then be safely divided in the subcutaneous plane superficial to the SMAS.

Some of the zygomatic and buccal branches can be less than 1 mm deep to the SMAS in the region adjacent to the upper masseteric ligaments, and therefore this region must be approached with extreme caution.

A relatively safe area of dissection is directly over the zygomatic eminence, an area that is relatively free of facial nerve branches.

7.3.3 Marginal Mandibular Branch

Always stay superficial to the platysma-SMAS.

It is important to note that the platysma can be particularly atrophic, thin, and lax, making the dissection at times difficult as the proper plane is not clear when dissecting in the lower cheek.

When transitioning from the preplatysmal plane caudally in the neck and along the jaw line, careful dissection is necessary to avoid getting deep to the platysma along the caudal border of the masseter.

Caution should be taken around the region where the facial vessels cross the mandible anterior to the mandibular tuberosity as the marginal mandibular nerve becomes more superficial while crossing over the vessels.

7.3.4 Cervical Branch

Staying superficial to the platysma will protect the cervical branches.

7.4 Staying Safe to Prevent Injury to the Facial Nerve during SMAS Elevation

The majority of SMAS elevation occurs overlying the parotid, the accessory lobe of the parotid, and the lateral zygoma, all regions where facial nerve branches are protected.

Anterior to the parotid and along the region lateral to the zygomatic eminence are the areas where the facial nerve branches are susceptible.

Limiting the dissection within the mobile region of the SMAS minimizes the risk to motor nerve injury, which are more exposed in the anterior region of the cheek.

Directly lateral to the zygoma, the SMAS requiring dissection tends to become thin as it transits from the lateral cheek superiorly along the superficial surface of the zygomaticus major.

Accurate plane identification is essential in this region of the dissection, for both motor branch protection as well as to not tear the SMAS flap as it is dissected from the upper masseteric ligaments.

Once the SMAS is dissected from the upper masseteric ligaments, the mobile region of the SMAS is encountered, and dissection should be terminated. This limits the dissection just cephalad to the juxtaposed zygomatic nerve branches, which are commonly found in the plane between the SMAS and the deep fascia in this region.

Dissection anteriorly along the superior malar eminence, superficial to the zygomaticus major, is critical for malar pad repositioning. Facial nerve branches are protected (deep to the zygomaticus major) in the region directly overlying the zygoma.

The inferior SMAS dissection should extend along the lateral boarder of the platysma and free the lateral platysma from its ligamentous attachments to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) to ensure adequate flap mobility. Once the SMAS/platysma is free from the SCM, an areolar plane is encountered, which can dissected bluntly, minimizing risk to the underlying cervical and marginal branches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree