differentiation in black patients with hypopigmentation as a postinflammatory sequelae of the original inflammatory condition, for example, eczema or psoriasis. Pityriaisis versicolor enters the differential diagnosis at extragenital sites. The main diffential diagnosis in the anogenital area is lichen sclerosus. This has a similar marble white color, but the crinkled, rough textural changes in the skin help to differentiate this condition. A confusing picture arises with the relatively common coexistence of both vitiligo and lichen sclerosus. The anesthetic, hypopigmented patches of leprosy may also mimic vitiligo, but testing for sensation within the white skin is normal in vitiligo. Vitiligo-like change can be induced by the topical immunonmodulatory cream, imiquimod, used for treating genital warts (3).

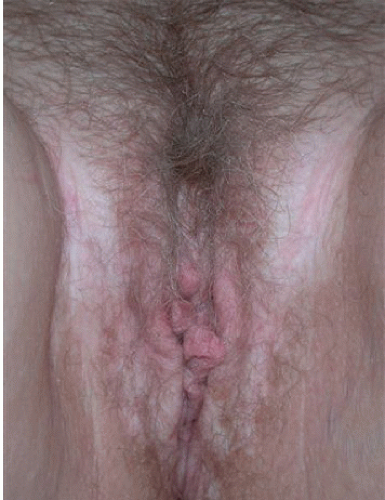

FIG. 11-1. This patient with vitiligo has depigmented patches without surface texture change and associated patchy peripheral hyperpigmentation. |

VITILIGO: | Diagnosis |

| |

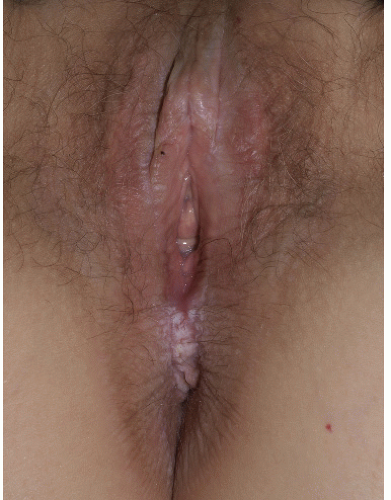

FIG. 11-2. Vitiligo tends to occur first on the glans, and patchy hyperpigmentation may or may not occur. |

VITILIGO: | Management |

| |

POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPOPIGMENTATION: | Diagnosis |

| |

that caused the problem is still present, this should be treated to prevent further hypopigmentation.

FIG. 11-4. This child still shows remaining erythema and roughness from her diaper rash; the area of pigment lightening is characteristic of postinflammatory hypopigmentation. |

POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPOPIGMENTATION: | Management |

| |

stratified epithelium. There can be involvement of the modified mucous membrane at junctional zones such as the vestibule, but the vagina is never involved. Perianal involvement appears to occur exclusively in female patients.

FIG. 11-5. Although at first glance, these very light papules mimic vitiligo, the crinkled texture change is pathognomonic for lichen sclerosus rather than vitiligo. |

FIG. 11-6. This woman presented with severe itching, so scratching in the setting of the fragility typical of lichen sclerosus resulted in the classic finding of purpura. |

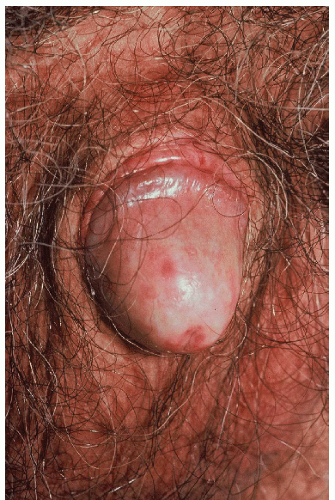

FIG. 11-9. The texture change of lichen sclerosus in this patient is manifested by shininess. The glans and inner prepuce are the most commonly affected areas. |

cornified epithelium surrounding the urethral meatus and lower part of the urethra (Fig. 11-16).

FIG. 11-11. Very early lichen sclerosus can be quite subtle, with mild hypopigmentation, poorly demarcated borders, and even a more waxy texture as pictured here in the anterior, interlabial fold. |

sclerosus are extremely uncommon, and most of the lesions seen involve the frictional sites which can become cornified, on the buccal mucosae, dorsal aspect of the tongue, and attached gingivae (6).

FIG. 11-13. Severe scarring occurs in some women as well as men; all vulvar architecture has been obliterated in this elderly woman with longstanding disease. Urinary obstruction occasionally occurs. |

FIG. 11-14. Lichen sclerosus can produce phimosis, and it is the most common cause of phimosis in boys. (Courtesy of Errol Craig, MD.) |

FIG. 11-15. Lichen sclerosus in male patients occurs most often on the glans, corona, and inner prepuce; scarring of the corona to the shaft has begun in this man. |

FIG. 11-17. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) can present as red plaques within lichen sclerosus. |

overlies a band of hyalinization in the upper dermis with a mixed lymphocytic infiltrate immediately below it. In some areas, small foci of lichenoid change are found where the infiltrate abuts the dermoepidermal junction. Rarely, the epidermis exhibits the histologic features of squamous cell hyperplasia, that is, it is thickened (acanthotic). This is important as there seems to be an association with this kind of change and development of squamous cell carcinoma.

LICHEN SCLEROSUS: | Diagnosis |

| |