Pigmented Disorders

Peter J. Lynch

Pigmented lesions are present on the skin of the genitalia in approximately 10% to 12% of women and a slightly smaller proportion of men. The etiologic basis for these pigmented lesions includes physiologic hyperpigmentation, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, some infections, and benign and malignant neoplasms. The brown and black colors usually arise as a result of melanin pigmentation. Melanin pigment is made within cytoplasmic organelles (melanosomes) in melanocytes that lie along the basement membrane of the epithelium. The amount of color in both normal skin and various lesions is determined by several factors: the density of melanocytes, the amount of melanin produced per melanocyte, and the transfer rate of the melaninized melanosomes to the 30 or so keratinocytes that surround each melanocyte. The density of melanocytes does not vary appreciably in people of different racial backgrounds but it does vary by site. Genital tissue, for instance, has about 50% more melanocytes per unit of area than does trunkal skin. The development of increased pigmentation is partially dependent on genetic factors (variability in racial groups) and partly on acquired factors such as ultraviolet light, the presence of inflammation (especially that involving basal layer damage), and some kinds of infection (notably human papillomavirus [HPV] infection in the genital and perigenital areas). Increased pigmentation also occurs when there is proliferation in the number of normally melanized keratinocytes (epithelial hyperplasia) and/or when there is an increased retention of normally melanized keratinocytes in the stratum corneum. For a few disorders in this chapter, heme pigment rather than melanin explains the presence of a dark color.

PHYSIOLOGIC HYPERPIGMENTATION

Physiologic hyperpigmentation occurs as symmetrical, flat, smooth-surfaced, asymptomatic darkening of the skin. The most commonly affected sites include the scrotum in male patients and the labia majora and outer edges of the labia minora in female patients (Fig. 13-1). The perianal skin in both genders usually displays some degree of physiologic hyperpigmentation. Appreciable variation in hue occurs across racial groups and also from person to person even within a given racial group. The degree of hyperpigmentation can be so light that it is hardly noticeable or may be so dark as to be almost black in color.

The diagnosis of physiologic hyperpigmentation is made on a clinical basis. The differential diagnosis includes postinflammatory hyperpigmentation but the latter tends to be patchier and is often less symmetrically distributed. If biopsy is carried out because of either patient or clinician concern, increased melanin will be found in both the melanocytes and keratinocytes which line the basal layer of the epithelium. Hyperpigmentation occurs preferentially in genital skin because of the greater density of melanocytes in this tissue compared to the surrounding skin. These areas of hyperpigmentation will darken further under the influence of both endogenous and exogenous sex hormones. This is particularly notable during pregnancy. Darkening will also occur due to the presence of increased melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) in neonates and in patients with disorders such as Addison disease due to the marked disturbance in pituitary-adrenal axis function.

Treatment is not necessary or even desirable. However, it is worth noting that obsession with anogenital hyperpigmentation has led to the provision of bleaching services by both licensed and unlicensed practioners.

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

Acanthosis nigricans was an uncommon disorder 50 year ago, but it has become very prevalent in recent years due to the epidemic of obesity, especially in children. In a recent survey of pediatric practices, obesity (body mass index > 95th percentile) was found in about 32% of the children and teenagers. Of these overweight patients, more than 62% were noted to have acanthosis nigricans and it was particularly prominent in the Hispanic and African American children (1). While acanthosis nigricans is most often found in those who are obese, it can also occur with various endocrinopathies, malignancies, and with the use of medications such as niacin, topical fusidic acid, and prednisone.

Acanthosis nigricans appears as poorly demarcated light-brown to dark-brown lesions around the neck, in the axillae, and in the crural folds (Figs. 13-2 and 13-3).

Rarely, it develops in other folded areas of the body. The background of hyperpigmentation may be flat but characteristically there are elevated linear ridges running parallel to one another. The surface of the lesions is slightly “bumpy” and, on palpation, is often velvety or very slightly rough. Acanthosis nigricans is asymptomatic but is very troubling to the patient because it suggests the appearance of dirty skin. The diagnosis is established clinically. The major disorder to be considered in the list of differential diagnoses is those instances of lichen simplex chronicus in which postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has occurred.

Rarely, it develops in other folded areas of the body. The background of hyperpigmentation may be flat but characteristically there are elevated linear ridges running parallel to one another. The surface of the lesions is slightly “bumpy” and, on palpation, is often velvety or very slightly rough. Acanthosis nigricans is asymptomatic but is very troubling to the patient because it suggests the appearance of dirty skin. The diagnosis is established clinically. The major disorder to be considered in the list of differential diagnoses is those instances of lichen simplex chronicus in which postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has occurred.

FIG. 13-1. Physiologic hyperpigmentation of the vulva may be most marked on the labia minora and, sometimes, on the posterior fourchette. |

FIG. 13-2. Acanthosis nigricans is manifested by hyperpigmentation in skin folds, often with a velvety appearance. |

FIG. 13-3. Acanthosis nigricans is most common in overweight individuals, and more severe acanthosis nigricans shows not only more thickened appearing skin but may also be associated with skin tags. |

There is no dermatologic therapy for acanthosis nigricans but the appearance can be improved through weight loss or treatment for any associated endocrinopathy. Medical evaluation of patients with acanthosis nigricans is usually desirable because of the frequently associated presence of insulin resistance, abnormal glucose homeostasis, hypertension, and elevated cholesterol (2). Very rarely acanthosis nigricans is associated with the development of systemic malignancy, especially that involving the gastrointestinal tract. This association should be considered in those individuals who are nonobese, lack endocrinopathy, and/or have a recent history of unintentional weight loss.

POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPERPIGMENTATION

Inflammation affects melanocytes in two ways. Severely damaged melanocytes discontinue the production of melanin with resulting hypopigmentation. Conversely, mildly damaged (“irritated”) melanocytes react with increased melanin production and hyperpigmentation. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops at the site of previous inflammation. This inflammation may be either an inherent component of a skin disease or the inflammation may develop at the site of trauma such as might occur following the use of liquid nitrogen or trichloroacetic acid. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is clinically recognized as light- to dark-brown, nonpalpable macules and patches occasionally displaying hues of gray, blue, or black (Fig. 13-4). The

distribution, location, and intensity of hyperpigmentation are dependent on the underlying cause.

distribution, location, and intensity of hyperpigmentation are dependent on the underlying cause.

FIG. 13-4. This patient has been picking at her skin, and the open excoriation is accompanied by healed lesions that show poorly demarcated brown-pink macules of postinflamamtory hyperpigmentation. |

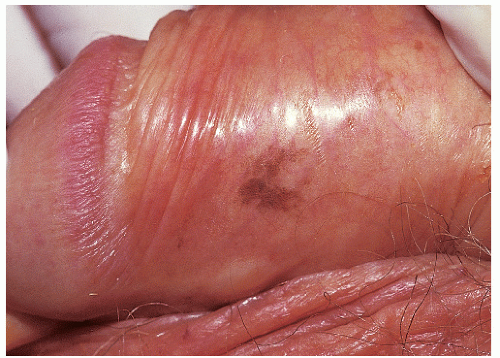

Diseases such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, in which inflammation preferentially damages the epithelial basal layer, are likely to develop darker pigmentation than occurs with other inflammatory disorders (Figs. 13-5 and 13-6). Not surprisingly, patients with racially or nationally darker skin are more likely to develop exaggerated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Similarly, because normal genital color is often darker than surrounding skin, inflammation in genital tissue is particularly likely to cause postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Although a history of prior trauma or inflammation is an important diagnostic clue, often such a history cannot be evoked. This is particularly true in lichen planus and lichen sclerosus where the extraordinarily long-lasting hyperpigmentation may first be noted a very long time after the inflammation has resolved. In this situation, the coexistence of architectural damage and pigmentation may identify the nature of the process. In some instances, a biopsy will be necessary to confirm a clinical diagnosis of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. This is particularly true for pigmented macules or patches where the pigment is variable in density or where gray or black hues are present (see the sections on melanosis and nevi).

Because postinflammatory hyperpigmentation usually resolves over several months, no treatment is necessary. However, the hyperpigmentation sometimes obscures continuing low-grade inflammation and when there is any suspicion of this possibility, anti-inflammatory treatment, such as with topical steroids, should be administered. Topical fading agents, such as hydroquinone, may improve pigmentation where the excess melanin is confined to the epidermis but are of no use

for pigment lying below the epithelium in dermal melanophages.

for pigment lying below the epithelium in dermal melanophages.

FIG. 13-5. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs occasionally on modified mucous membranes following lichen planus or lichen sclerosus. This woman has partially treated lichen sclerosus. |

SEBORRHEIC KERATOSES

Seborrheic keratoses are extremely common benign growths. Most individuals over the age of 40 have at least one lesion and often 50 to 100 are present. Most are located on the trunk but occasionally they are noted on the proximal limbs and genitalia. Seborrheic keratoses present as sharply marginated, square-shouldered, tan, brown, or black papules 10 to 15 mm wide and 2 to 10 mm tall (Figs. 13-7 and 13-8). These attributes contribute to a characteristic “stuck on” appearance. The surface often contains visible scale and is usually rough on palpation. However, in some instances, the surface has a smooth and “waxy” feeling. In these smooth lesions, the presence of scale can be identified when the surface is gently scraped with a blade held perpendicular to the top of the lesion. The presence of scale is a very helpful point in distinguishing seborrheic keratoses from nevi, lentigines, and melanomas. Small characteristic surface pits may be found when magnification is used in the course of examination.

Genital seborrheic keratoses may be quite difficult to differentiate from both pigmented genital warts and HPV-related intraepithelial neoplasia. The number of lesions present is a helpful clue. Genital seborrheic keratoses are generally solitary, whereas HPV-related lesions are almost always more numerous. Seborrheic keratoses may also resemble pigmented basal cell carcinomas, normal nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. Scale is, of course, not present in these latter lesions, but when scale is absent or sparse, differentiation is not easy. For all of these reasons, unless they are completely typical in appearance, there ought to be a low threshold for biopsy. Support for this statement is offered by the observation that in a large study of biopsied lesions thought to be seborrheic keratoses, 0.5% turned out to be melanomas (3).

FIG. 13-7. The seborrheic keratosis on the penile shaft shows typical well-demarcated borders, and the surface is slightly stippled with pinpoint dark keratin plugs. |

The cause of seborrheic keratoses is unknown but frequent presence of familial patterns regarding both age at onset and number of lesions suggests that both genetic and aging factors play a role. Growth factors may also be important even as they are in many other cutaneous neoplasms. Specifically, a small proportion of seborrheic keratoses contain mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene and a larger proportion demonstrates activation of the same normal (nonmutated) gene (4). Beta-type (epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated) HPV is found more commonly in seborrheic keratoses than in normal skin but the meaning of this is not clear (5). In many previous reports, seborrheic keratoses occurring in and around the genitalia were found to contain alpha-type HPV (mucocutaneous wart type) and thus presumably were in reality pigmented genital warts (6).

No therapy is necessary for clinically typical seborrheic keratoses. Lesions that are irritated by clothing and those that are particularly bothersome to the patient may be treated with liquid nitrogen.

PIGMENTED WARTS

Genital warts of the flat-topped type are frequently tan, brown, or black in color (Figs. 13-9 and 13-10). These lesions are covered along with other morphologic types of warts in Chapter 12.

GENITAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA

HPV-related vulvar, penile, and scrotal intraepithelial neoplasia is frequently tan, brown, or black in color (Figs. 13-11 and 13-12). These conditions are discussed in Chapter 12.

PIGMENTED BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

Basal cell carcinomas are normally skin colored but a small proportion contain sufficient melanin to be at least partially brown, blue, or black in color (Fig. 13-13). These lesions are covered in Chapter 12.

ANGIOKERATOMAS

Genital angiokeratomas are usually light to dusky red in color but those occurring on the vulva are sometimes blue, purple, or black (Figs. 13-14 and 13-15). These lesions are covered in Chapter 7.

FIG. 13-12. When a person of light complexion has hyperpigmented, flat-topped genital warts, intraepithelial neoplasia is extremely likely, as is true in this patient. |

KAPOSI SARCOMA

The nodules of Kaposi sarcoma occurring on the trunk and genitalia are usually medium to dusky red in color. Less often they are darker in color and may have blue, purple, or even black hues (Fig. 13-16). This neoplasm is discussed in Chapter 7.

GENITAL VARICOSITIES

Varicose veins occur on the vulva with some frequency in pregnant women and they often resolve following parturition (7). Varicosities are less common on the penis and scrotum. The varicosities may be small or large. Larger lesions are usually blue in color (Figs. 13-17 and 13-18). Very small diameter vessels (“spider veins”) are more likely to be medium to dark red. On the scrotum, tiny angiokeratomas may overlie these fine, red telangiectatic vessels. Varicosities are identified by their disappearance following compression with a glass slide (diascopy). No treatment is ordinarily necessary but bleeding following trauma may require electrosurgery or even excision.

FIG. 13-14. An angiokeratoma is often so deeply purple that it appears black. This lesion must be differentiated from a nodular melanoma. |

FIG. 13-15. When multiple lesions are present, angiokeratomas are more easily diagnosed, as at least some lesions usually reveal the underlying vascular nature by red or purple color. |

GENITAL MELANOSIS (LENTIGINOSIS)

Clinical Presentation

The terms genital melanosis and genital lentiginosis are often used interchangeably by clinicians but, strictly speaking, the latter term is only applicable to those lesions that demonstrate a lentigo-like histologic pattern on biopsy. Since this is not present in all cases, we prefer the term genital melanosis. Pigmented lesions of melanocytic type are common on the genitalia, with a prevalence estimated to be about 10% to 15% in women and in a slightly lower percentage in men (8). In women, histologic examination of flat pigmented patches reveals that about one third of the lesions are nevi with the remainder representing vulvar melanosis (9,10).

FIG. 13-19. Genital lentiginosis is characterized by poorly demarcated or irregular, macular hyperpigmentation. |

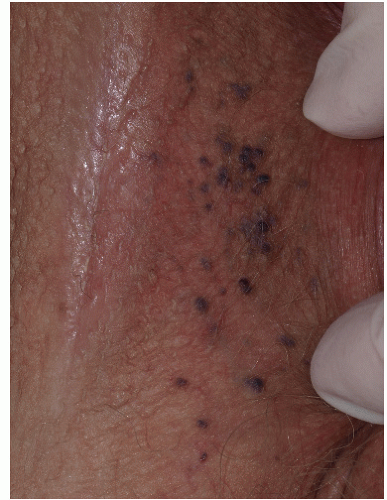

Genital melanosis consists of nonpalpable, nonelevated macules and patches of dark, usually black, pigmentation (Figs. 13-19, 13-20 and 13-21). This pigmentation occurs on both keratinizing skin and mucous membranes but is more common at the latter site. Genital melanosis is particularly likely to arise from a background of lichen sclerosus (Fig. 13-22). Lesions may be either solitary or

multifocal with the latter occurring more frequently. Lesions may be as small as 5 mm but most are considerably larger with diameters up to 2 cm. Asymmetry in distribution is common and the configuration is at times quite angular. The color may be tan, brown, blue, or, most commonly, black. Often there is considerable variation in pigment density within the lesions. The borders may be either diffusely or sharply marginated. In men, given the ready visibility of the penis, there may be a history of long duration with little or no change in appearance but for women the duration is often unknown. In women, the pigmented patches are most often found on the labia minora. The labia majora are less frequently involved and vaginal and perineal lesions are only rarely encountered. In men, most lesions occur on the glans and inner aspects of the prepuce but penile shaft involvement is possible.

multifocal with the latter occurring more frequently. Lesions may be as small as 5 mm but most are considerably larger with diameters up to 2 cm. Asymmetry in distribution is common and the configuration is at times quite angular. The color may be tan, brown, blue, or, most commonly, black. Often there is considerable variation in pigment density within the lesions. The borders may be either diffusely or sharply marginated. In men, given the ready visibility of the penis, there may be a history of long duration with little or no change in appearance but for women the duration is often unknown. In women, the pigmented patches are most often found on the labia minora. The labia majora are less frequently involved and vaginal and perineal lesions are only rarely encountered. In men, most lesions occur on the glans and inner aspects of the prepuce but penile shaft involvement is possible.

FIG. 13-20. The irregular nature of genital lentiginosis or melanosis is often suggestive of melanoma, so any lesion with this appearance should undergo biopsy. |

FIG. 13-21. Although brown, black, and gray patches are rather wild in appearance, large number of discrete lesions suggests a benign nature. |

Most cases of genital melanosis develop in adult life with an average reported age of about 40 (8). When young patients present with genital melanosis, the oral mucous membranes should be inspected for the presence of similar pigmentation. When this is found, consideration should be given to the possibility of any one of a number of rarely encountered conditions such as Peutz-Jehgers syndrome, Laugier-Hunziger syndrome, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, LEOPARD syndrome, and the several syndromes in which lentigines and cardiocutaneus myxomas are found.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made on a clinical basis in many cases but, unless a long history of stable appearance is available, biopsy should be undertaken to rule out postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, pigmented intraepithelial neoplasia, dysplastic nevus, lentigo maligna, lentigo maligna melanoma, and superficial spreading melanoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree