Red Plaques and Patches

Libby Edwards

The usually characteristic appearance of individual skin diseases is modified by the environment in skin folds, so that diagnosis by morphology is challenging. Moisture and heat obscure scale. Subtle lichenification (thickening from rubbing) sometimes appears white due to hydration. Normally well-demarcated borders of lesions may appear fuzzy as friction irritates the skin. Also, genital skin, even more than dry, keratinized skin, often is affected by more than one disease process, so secondary infection and irritation from sweat, urine, feces, and overwashing can change the appearance of the skin. In addition, redness is difficult to detect when occurring in a patient with a naturally dark complexion; erythema is generally perceived as hyperpigmentation in this population.

Often, the correct diagnosis of red genital plaques and patches depends on the identification of more typical morphology on other areas of the body, and, when in doubt, a skin biopsy is sometime helpful. Unfortunately, a skin biopsy of nonspecific erythema often yields a nonspecific result. Often, empiric corticosteroid therapy while monitoring or treating for likely infections is necessary. Red plaques and patches that are not diagnosed clinically or do not respond to therapy as expected should be biopsied to rule out the occasional extramammary Paget disease or intraepithelial neoplasia (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ, Bowen disease, or erythroplasia of Queyrat).

ATOPIC DERMATITIS, ECZEMA, AND LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS (discussed primarily in Chapter 4)

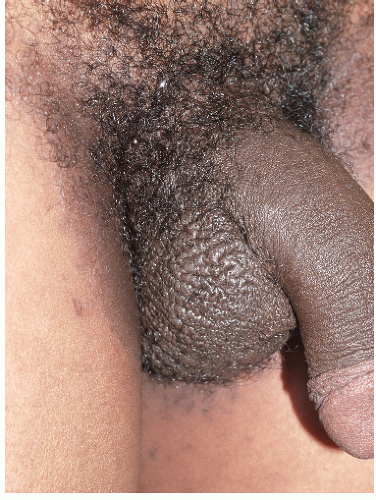

Because rubbing and scratching produce the visible signs of eczema, the appearance varies, depending on the individual tendency to rub, scratch, or both, and any tendency of the patient’s skin to thicken in response to rubbing or scratching. A person who rubs exhibits thickened, lichenified skin with increased skin markings or occasionally excessive smoothness, as though the skin has been polished by rubbing (Figs. 6-1, 6-2 and 6-3). Skin that has been scratched is red with excoriations (Fig. 6-4). Usually, the plaques are poorly demarcated since a general area is rubbed or scratched, and the area may simply show a generalized area of irritation.

Scale and excoriation are often subtle because of moisture and thin skin, and erythema may be relatively unremarkable because the genitalia are frequently pink normally. Erythema can be especially difficult to detect in patients with normally dark skin, when inflammation often appears hyperpigmented rather than red.

The diagnosis of eczema in the genital area is normally made by a combination of a history of itching with intense pleasure on scratching, morphology, and the exclusion of infection that can produce itching, especially candidiasis and dermatophytosis. The diagnosis is confirmed by the excellent response to standard therapy.

A mainstay in the treatment of eczema includes the elimination of irritants, especially overwashing; protection from urine, feces, and perspiration; avoidance of irritating lubricants and topical medications; and the discontinuation of panty liners. Scratching is a potent irritant, and bedtime sedation to prevent nighttime scratching is crucial. The specific medication of choice is the application of a potent topical corticosteroid ointment such as clobetasol sparingly twice daily initially, tapering the frequency or the potency when the skin becomes normal. Topical tacrolimus (Protopic) ointment 0.1% and pimecrolimus (Elidel) cream are calcineurin inhibitors approved for use in eczema (1,2). These can be irritating on the genitalia, are expensive, and are less effective than potent corticosteroids for eczema. Although these characteristics make these medications second-line therapy for genital eczema after corticosteroids, these can be useful for some patients who require chronic therapy. As with other chronic skin diseases, an ongoing high index of suspicion for and therapy of infection is important (3). Finally, patient education is extremely important in the treatment of eczema. Patients must realize that this is a chronic skin disease that often requires chronic or intermittent therapy.

CONTACT DERMATITIS (discussed primarily in Chapter 4)

Contact dermatitis is an eczematous reaction in response to either an irritant or an allergen. Although any patient will develop skin changes and symptoms after contact with a sufficiently irritating substance, only patients specifically sensitized to an allergen develop allergic contact dermatitis. The poorly keratinized nature of much of the genitalia and the damp environment result in increased permeability of the skin, and a resulting

increased risk for contact dermatitis compared to other skin surfaces (4).

increased risk for contact dermatitis compared to other skin surfaces (4).

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

This extremely common dermatitis is a frequent secondary factor in patients with genital symptoms, often associated with overwashing, use of topical medications, and chronic moisture from incontinence or sweat.

FIG. 6-2. Deep erythema, edema, and scale of this eczematized scrotum are characteristic of chronic rubbing and scratching. |

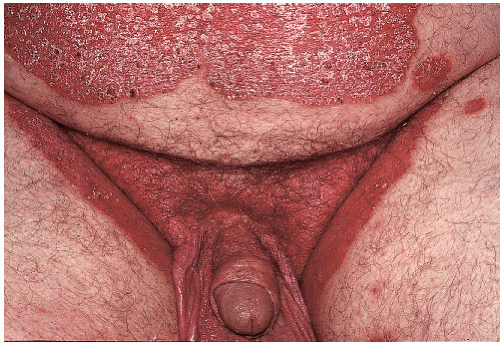

Chronic irritant contact dermatitis is usually manifested by symptoms of irritation, soreness, or rawness. If the patient is atopic, the irritant can precipitate itching and can initiate an itch-scratch cycle. Morphologically, the area affected depends on where the contact occurred. Generally, this is manifested by a poorly demarcate

erythematous or dusky plaque with scale that may be subtle (Fig. 6-5). Patients who have experienced itching frequently have superimposed excoriations or lichenification. In these patients, the morphology is indistinguishable from that of atopic dermatitis, and indeed the irritant can be viewed simply as a precipitating factor for atopic dermatitis or eczema. Acute irritant dermatitis is essentially a chemical burn. The rapid appearance of erythema, edema, and blistering is typical. Poorly keratinized skin such as the modified mucous membranes of the vulva, the glans penis, and the inner aspect of the prepuce is very fragile, and blister roofs are shed quickly, forming erosions.

erythematous or dusky plaque with scale that may be subtle (Fig. 6-5). Patients who have experienced itching frequently have superimposed excoriations or lichenification. In these patients, the morphology is indistinguishable from that of atopic dermatitis, and indeed the irritant can be viewed simply as a precipitating factor for atopic dermatitis or eczema. Acute irritant dermatitis is essentially a chemical burn. The rapid appearance of erythema, edema, and blistering is typical. Poorly keratinized skin such as the modified mucous membranes of the vulva, the glans penis, and the inner aspect of the prepuce is very fragile, and blister roofs are shed quickly, forming erosions.

FIG. 6-4. Excoriations as well as inflammation and lichenification are additional signs of scratching. |

FIG. 6-5. Overwashing produced this inflamed, edematous, red plaque of irritant contact dermatitis with interlabial fissures. |

Irritant contact dermatitis can be caused either by repeated exposure to a weak irritant or by one or few exposures to a very strong irritant. Common irritants are listed in Table 6-1. A diaper rash is a typical example of chronic irritant contact dermatitis, although in this case superimposed candidiasis is sometimes a complicating factor. Because repeated exposure is often necessary for the development of irritant contact dermatitis and the symptoms and signs occur gradually, the patient is frequently unaware that the substance is irritating and is playing a role in symptoms.

Acute irritant contact dermatitis, however, is produced by one or a few exposures to a very strong irritant, and this exposure is often accompanied by immediate burning and stinging. The patient usually is aware of the cause of the symptom and frequently misinterprets this as allergy. The most common causes of acute irritant contact dermatitis include treatment for external genital warts, such as trichloroacetic and bichloroacetic acids, podophyllum resin, and cantharidin. Some patients with very sensitive skin can experience acute irritant contact dermatitis to alcohol-containing creams, most often antifungal medications used in a setting of pre-existing inflamed skin.

TABLE 6.1 Common irritants | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The diagnosis of irritant contact dermatitis is made by correlation of the symptoms and physical findings with a history of possible contactants. The diagnosis is confirmed when the contactants are eliminated and the eruption and symptoms resolve. Dermatoses with similar morphology include eczema/lichen simplex chronicus and allergic contact dermatitis. Psoriasis, vulvar/penile/anal intraepithelial neoplasia (Bowen disease) and Paget disease can also resemble irritant contact dermatitis. Acute irritant dermatitis can be confused with other blistering or ulcerative conditions, including acute allergic contact dermatitis, herpes simplex virus infection, a fixed drug eruption, or candidiasis. Autoimmune blistering diseases are slower in onset and are less likely to produce diagnostic confusion.

The most important aspects of therapy are the identification and elimination of all irritants. A midpotency topical corticosteroid ointment, such as triamcinolone 0.1% twice a day is often useful. The pain and burning of acute irritant contact dermatitis are minimized by cool or tepid tap water sitz baths several times a day for the first few days, followed by the application of petrolatum on open erosions. Nighttime sedation provides comfort and sleep to those with pain and itching and minimizes ongoing irritation from nighttime scratching.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs as a result of contact of an allergen to the skin of a patient who has specifically developed a hypersensitivity to that allergen.

FIG. 6-6. Benzocaine obtained over the counter and applied for itching has resulted in these tiny, coalescing vesicles of allergic contact dermatitis. |

Chronic allergic contact dermatitis is characterized by itching as well as by a poorly demarcated erythematous, scaling plaque that often shows linear erosion from scratching and lichenification. Often, chronic allergic contact dermatitis cannot be distinguished clinically from irritant contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis and its variants. Acute allergic dermatitis, however, presents with cutaneous edema that produces tiny, monotonous, closely set vesicles in the areas of the contact (Fig. 6-6). Often, there are linear or irregular plaques in which the contactant was spread on the skin, such as by fingers for medication or brushed on by the leaves of a plant.

The allergen is rarely recognized by the patient, because symptoms follow exposure by one or several days. Allergic contact dermatitis has been found by European clinicians to play a significant role in chronic vulvovaginal symptoms, whereas American physicians have not found allergy to be a common factor (5). More common allergens are listed in Table 6-2.

The diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis is made by correlation of symptoms and physical findings with a history of a likely contactant. The diagnosis is confirmed when the contactant is eliminated and the eruption and symptoms resolve. Sometimes, allergic contact dermatitis is suspected when atopic dermatitis does not respond to therapy, but an allergen is not identified. In these cases, patch testing by a dermatologist is warranted to identify any offending allergens.

TABLE 6.2 Causes of allergic contact dermatitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The differential diagnosis of chronic allergic contact dermatitis includes irritant contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis/lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, secondarily rubbed or scratched tinea cruris, candidiasis, seborrheic dermatitis, vulvar/penile/anal intraepithelial neoplasia (Bowen disease), and Paget disease. Acute allergic contact dermatitis can be confused with other blistering or erosive diseases, especially acute irritant contact dermatitis, candidiasis, and herpes simplex virus infection.

Most important in the treatment of contact dermatitis is the elimination of the contactant. Sometimes, the contactant cannot be identified, and the patient is counseled to avoid all topical agents other than clear water and petrolatum (petroleum jelly). After the elimination of the contactant, acute, blistering, or exudative contact dermatitis can be improved with cool soaks or sitz baths for the first few days. Oral prednisone for severe disease and topical corticosteroids for less erosive dermatitis are useful as well. Topical corticosteroids should be continued until symptoms are clear and the skin is normal. Nighttime sedation and control of secondary infection are important to minimize symptoms while the skin heals.

SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS (also discussed in Chapter 4)

Seborrheic dermatitis is an uncommon cause of genital skin disease in adults, although seborrhea of the scalp is extraordinarily common (see also Chapter 12).

Clinical Presentation

Seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp is a common disease, occurring at all ages. However, seborrheic dermatitis is most common in newborns and after puberty. In addition, this condition is most severe in those who cannot shampoo regularly, such as the homeless and those with neurologic disease or other infirmities that interfere with activities of daily living. Finally, patients of African background cannot shampoo daily because of the excessive dryness of their hair with frequent washing.

Seborrheic dermatitis generally affects the scalp first and most remarkably. Erythematous plaques at the hairline exhibit yellowish scale with a slightly greasy texture, hence the term seborrhea. As the disease worsens, the entire scalp becomes involved, and erythema and scale spread to other areas, preferentially affecting the ears, posterior auricular folds, eyebrows, and the nasolabial folds. Most often, seborrheic dermatitis does not extend beyond these areas. Occasionally, however, severe seborrheic dermatitis can involve the entire face, and the eruption can spread to the chest and to skin folds including the axillae, umbilicus, and genital skin (Fig. 6-7).

Seborrheic dermatitis of the genital area is accentuated within the skin folds. A classic but not unique characteristic of genital seborrheic dermatitis is a glazed, shiny texture to the affected skin.

Infants often develop seborrhea of the scalp, also called cradle cap. Spread of the eruption to the face, trunk, and genitalia is much more common in infants than in adults.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis can generally be made by the pattern of red, scaling plaques that include the scalp, central face, and other skin folds and by the absence of negative culture or skin scrapings for candidiasis. A biopsy is generally not required to make this diagnosis, but histology is characterized by varying degrees of acanthosis and elongation of the rete ridges, with hyperkeratosis and spongiosis. There is an underlying perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, with some migration into the epidermis. Neutrophils can be seen in the stratum corneum. The diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis is confirmed by the rapid and complete response to therapy.

Most causes of generalized red patches and plaques of the genitalia are in the differential diagnosis. This includes atopic dermatitis and its variants, allergic and irritant contact dermatitis, fungal infection, and psoriasis. The accentuation of disease in the skin folds especially mimics cutaneous candidiasis. Generally, these diseases can be differentiated by their pattern of involvement on other parts of the body, as well as by the characteristic yellowish, greasy scale on the scalp and face seen in seborrhea. Psoriasis, however, frequently exhibits the same distribution, but the thicker nature of the plaque, the more discrete rather than generalized scalp plaques, the psoriatic nail changes, and the typical lesions of psoriasis of other skin surfaces usually differentiate these two diseases.

SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS: Diagnosis

Morphology of red plaques in skin folds in a setting of red plaques in a typical distribution for seborrhea; scalp, central face, ears, chest, axillae

Patient who is an infant or unable to wash regularly; homeless, debilitated

Pathophysiology

The cause of seborrheic dermatitis is not known. Some evidence suggests that Malassezia yeasts, the causative organism of pityriasis (tinea) versicolor, play a role in the development of seborrheic dermatitis. Unencapsulated yeast forms stimulate cytokine production by keratinocytes (6). This yeast has been identified in the scalp of patients with seborrhea, and the antifungal cream ketoconazole topically is effective for the treatment of pityriasis versicolor and scalp seborrheic dermatitis. However, this organism is a frequent colonizer, and other equally effective antifungal medications have not been reported to be beneficial for the treatment of seborrhea; both of these facts suggest an alternate or additional etiology. Other clinicians believe that seborrhea is an inflammatory response to perspiration, heat, and sebum trapped under normal stratum corneum that is not normally shed from skin folds and hairy areas because of anchoring hair shafts. This theory is also used to explain the distribution of seborrhea, which includes the scalp, eyebrows, beard area, nasolabial and retroauricular folds on the head and neck, and other skin folds such as the axillae and groin (Fig. 6-7). Inflammation from heat, sweat and scale held against the skin by scale result in increased epidermal turnover and the production of even more scale.

Management

The treatment of anogenital seborrheic dermatitis requires the control of disease on the scalp and other areas as well. This involves the removal of scale from the scalp and any other affected hairy areas, as well as administration of topical corticosteroids. Vigorous and irritating

means of scale removal is not indicated in the much more sensitive skin folds and genital regions.

means of scale removal is not indicated in the much more sensitive skin folds and genital regions.

Brisk shampooing of the adult scalp with antiseborrheic shampoos containing antiproliferative agents such as tar zinc pyrithione or selenium sulfide or keratolytic substances such as salicylic acid aids in the debridement of scale from the scalp. Medication is scrubbed into the scalp and is allowed to stay on the skin for 5 to 10 minutes before it is rinsed. Generally, use of these shampoos in the genital area is not recommended because of their irritant properties and because they are not required for clearing. Again, because of the irritant properties of these shampoos, infant seborrhea is not treated with these agents. The scalp scale is softened with baby oil or mineral oil and is then removed with a soft brush or gentle use of fingernails.

Otherwise, topical corticosteroids are primary therapy for seborrhea, both on the scalp and on genital skin. Patients with mild disease and infants are easily treated with a lowpotency medication such as hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5%. For more severe disease, a midpotency topical corticosteroid such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream generally produces marked improvement quickly. An inexpensive, cosmetically pleasing, and effective corticosteroid for use in the scalp is betamethasone valerate 0.01% lotion, but this alcohol-based therapy should not be used on easily irritated genital skin.

For those patients who do not improve adequately with this safe and relatively inexpensive therapy, ketoconazole (Nizoral) cream or shampoo can be a beneficial treatment. The cream is applied twice a day, and the shampoo is used daily on the scalp.

The treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in patients of African descent must be modified because of the tendency for the hair of these patients to dry excessively and to break with overwashing. Twice-weekly vigorous shampooing of the scalp initially with careful attention to moisturizing the hair afterward is usually a reasonable compromise. However, moisturizers should be applied to the hair only, with the patient’s taking care to avoid application to the scalp itself because this can exacerbate retention of scale and occlusion.

Scalp seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic skin condition with a tendency to wax and wane in severity. Usually, the regular and proper use of an antiseborrhic shampoo controls scalp disease, although some patients require intermittent application of a corticosteroid solution to the scalp. Because the groin generally is the last area involved with severe seborrhea, control of scalp disease usually prevents the recurrence of anogenital seborrheic dermatitis.

SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS: Management

Ongoing removal of excess scale of the scalp by shampooing with keratolytic (salicylic acid) or tar shampoos

Topical corticosteroid cream (triamcinolone 0.1%) very sparingly twice a day until clear

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is a relatively common skin disease that frequently affects genital skin in addition to the elbows, scalp, and knees as classic locations.

Clinical Presentation

Psoriasis is a very common skin condition, occurring in 2% to 3% of people. Males and females are affected equally, and persons of African ancestry are less often affected than white individuals. This condition occurs at all ages but begins most often in young adults. There is a familial predisposition, with one in three patients reporting a family history of psoriasis.

Classic psoriasis vulgaris (common psoriasis) exhibits well-demarcated thickened, red plaques with dense, silvery scale (Figs. 6-8, 6-9 and 6-10). Often, patients report severe itching, but this is not universal. Plaques typically occur on the scalp, elbows, knees, umbilicus, and gluteal cleft. Genital involvement is common, and plaques are more generalized in patients with more severe disease. The face is usually relatively spared.

About 20% of patients exhibit Koebner phenomenon, in which psoriasis is precipitated in skin by irritation or injury. This partially explains the distribution of lesions, including the elbows and knees, as well as the frequent involvement of the genitalia, an area subject to friction and occlusion.

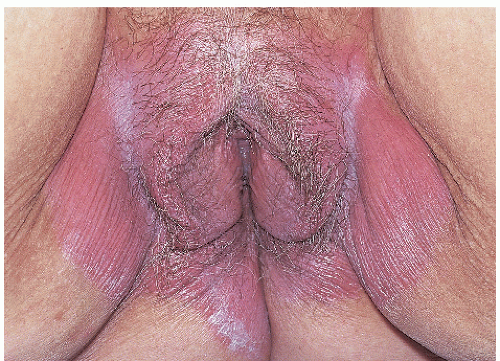

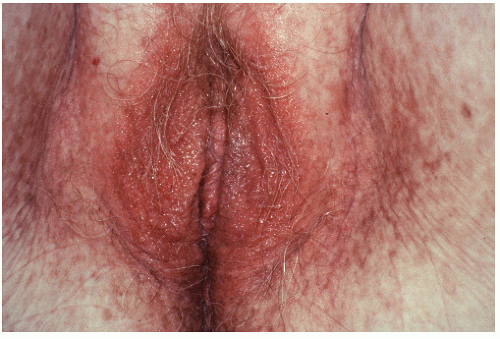

A variant of psoriasis that presents with prominent genital involvement is inverse psoriasis (Figs. 6-11, 6-12 and 6-13, 6-15, 6-17, 6-18 and 6-19). Inverse psoriasis involves skin folds preferentially and often spares the classic dry, keratinized knees, elbows, and scalps. The axillae, inframammary skin, umbilicus, gluteal cleft, crural creases, and genitalia are affected. Psoriasis occurring in skin folds exhibits very subtle scale as well as plaques that are far

thinner than psoriasis on other skin surfaces (Figs. 6-14, 6-15, 6-16 and 6-17). In addition, the borders frequently are less well demarcated (Fig. 6-18). Not uncommonly, yeast or dermatophyte infection may coexist with or may mimic intertriginous psoriasis (Fig. 6-19). Psoriasis predominantly affects the hairbearing vulva of women, mostly sparing the modified mucous membranes and vagina. However, psoriasis often is located on the glans penis in addition to the penile shaft, scrotum, and groin.

thinner than psoriasis on other skin surfaces (Figs. 6-14, 6-15, 6-16 and 6-17). In addition, the borders frequently are less well demarcated (Fig. 6-18). Not uncommonly, yeast or dermatophyte infection may coexist with or may mimic intertriginous psoriasis (Fig. 6-19). Psoriasis predominantly affects the hairbearing vulva of women, mostly sparing the modified mucous membranes and vagina. However, psoriasis often is located on the glans penis in addition to the penile shaft, scrotum, and groin.

FIG. 6-8. Classic psoriasis exhibits well-demarcated coalescing plaques with distinctive, heavy, silvery scale. |

FIG. 6-9. The circumcised penis shows scaling plaques that are thinner than those occurring on dry, fully keratinized skin. |

FIG. 6-10. Genital psoriasis often exhibits scale that is less dense than psoriatic scale on dry extragenital skin. |

FIG. 6-11. The gluteal cleft is a common location for psoriasis; redness is often marked in skin folds. |

Psoriasis sometimes can become generalized, so that confluent erythema, scale, and sometimes exudation are indistinguishable from generalized eczema or generalized seborrhea. A final form of psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, is characterized by plaques of pustules or crusting. This variant is discussed in Chapter 8.

Psoriasis produces nail abnormalities in addition to inflammatory skin lesions (Fig. 6-20). Most common are small nail pits, not to be confused with simple irregularity or rippling of the surface. Also fairly specific are “oil-drop spots.” These are brownish-red discolorations of the nail plate. A third form of nail psoriasis, onycholysis, is much

less specific. Onycholysis refers to lifting of the nail from the underlying surface, in this case from psoriasis of the nail bed. The scale and keratin debris collect under the nail, with the final picture nearly identical to that of a fungal nail infection.

less specific. Onycholysis refers to lifting of the nail from the underlying surface, in this case from psoriasis of the nail bed. The scale and keratin debris collect under the nail, with the final picture nearly identical to that of a fungal nail infection.

FIG. 6-12. Thick scale in moist skin folds appears as white, macerated skin, whereas the shiny, glazed red skin of the labia majora actually represents adherent scale. |

FIG. 6-14. Psoriasis of thin genital skin sometimes exhibits erosions as well as scale, which can be yellowish from serous exudate. |

FIG. 6-16. This poorly demarcated, thickened scrotal plaque is consistent with lichen simplex chronicus; however, the white, dense quality of the scale suggests the correct diagnosis of psoriasis. |

FIG. 6-18. Vulvar psoriasis is often poorly demarcated without psoriasiform scale, mimicking lichen simplex chronicus or contact dermatitis. |

The primary extracutaneous manifestation of psoriasis is arthritis. A significant minority of patients experience joint disease that ranges from pain with minimal inflammation to severe, deforming, and mutilating arthritis.

FIG. 6-20. In confusing diagnostic cases, the identification of typical psoriasis on other skin surfaces such as the scalp, elbows, or nail pits, such as these, can be very useful. |

There are also several comorbidities associated with psoriasis, suggesting that psoriasis is actually a complex constellation of systemic conditions. Patients with psoriasis are more likely to be obese, and alcoholism and depression are recognized as common occurrences. Cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and even osteoporosis have been reported more recently to occur more often (7,8). Autoimmune diseases also are increased in this group (9).

Diagnosis

Psoriasis of the genitalia can be diagnosed with confidence when morphologically consistent plaques in this area are associated with typical psoriasis of the elbows and knees, scalp, and nails. If the distribution and morphology are atypical, the diagnosis can often be confirmed on biopsy, but a nondiagnostic biopsy does not rule out psoriasis as a cause of the eruption.

The classic but nonspecific histologic picture of psoriasis includes marked thickening of the epidermis with regular elongation of the rete pegs and suprapapillary thinning. Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis are prominent, and there is an absence of the granular layer. More specific histologic findings are collections of neutrophils just under the stratum corneum of the thinned suprapapillary epidermis (spongiform pustules of Kogoj) and in the overlying parakeratotic layer (Munro microabscesses). A biopsy of an older lesion is often nonspecific and may be interpreted as psoriasiform dermatitis.

Tinea cruris is the most common disease confused with psoriasis, and they often coexist. However, in immunocompetent patients, tinea cruris usually spares the scrotum and penis, whereas these structures are often prominently affected with psoriasis. In addition, tinea

cruris is uncommon in women. Cutaneous candidiasis frequently shows satellite pustules or erosions but can also resemble and coexist with psoriasis. Lichen simplex chronicus, Bowen disease (also called squamous cell carcinoma in situ, as well as erythroplasia of Queyrat in men and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia on the vulva), and Paget disease are all red, scaling diseases that can be confused with psoriasis, and lichen planus on the glans penis is sometimes indistinguishable from smaller papules of psoriasis of this area. Seborrheic dermatitis, especially in infants, can appear very similar to psoriasis and shows the same pattern of distribution as inverse psoriasis.

cruris is uncommon in women. Cutaneous candidiasis frequently shows satellite pustules or erosions but can also resemble and coexist with psoriasis. Lichen simplex chronicus, Bowen disease (also called squamous cell carcinoma in situ, as well as erythroplasia of Queyrat in men and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia on the vulva), and Paget disease are all red, scaling diseases that can be confused with psoriasis, and lichen planus on the glans penis is sometimes indistinguishable from smaller papules of psoriasis of this area. Seborrheic dermatitis, especially in infants, can appear very similar to psoriasis and shows the same pattern of distribution as inverse psoriasis.

PSORIASIS: Diagnosis

Presence of well-demarcated red plaques in skin folds

Usually, more typical, heavily scaling plaques on other skin surfaces including elbows, knees, and scalp

Negative scrapings or cultures for Candida and dermatophytosis

In the absence of classic extragenital disease, biopsy, which shows acanthosis with regular elongation of the rete pegs and suprapapillary thinning, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis are prominent, absence of the granular layer. More specific are collections of neutrophils just under the stratum corneum of the thinned suprapapillary epidermis and within parakeratotic stratum corneum. Nonspecific “psoriasiform dermatitis” result is common

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree