Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection that is characterized by asymptomatic periods of varying duration, interrupted by three stages of clinical disease. In primary syphilis, a painless and nontender ulcer (“chancre”) develops, most often in or around the genitalia. The major discussion of syphilis will be found in this chapter with brief mention made of secondary syphilis in

Chapter 12. Although syphilis is a global problem, the data in this chapter refer primarily to syphilis in Western countries.

Clinical Presentation

According to the 2007 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) report, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States declined 90% from 1990 to 2000 at which point it reached its nadir (

1). Since then the rate has been steadily increasing. Most of this increase has been in men, primarily among men who have sex with men (MSM) (

1). This population now accounts for about 65% of all of the cases of early syphilis. In 2007, the incidence of syphilis was 6.6 per 100,000 for men and 1.1 per 100,000 for women. The rate is appreciably higher in Hispanic and African American men than that in non-Hispanic white men. Syphilis occurs most frequently between the ages of 20 and 24 in women and 20 and 30 in men. The data for Australia and European countries is quite similar to that found in the United States (

2,

3). Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is encountered frequently.

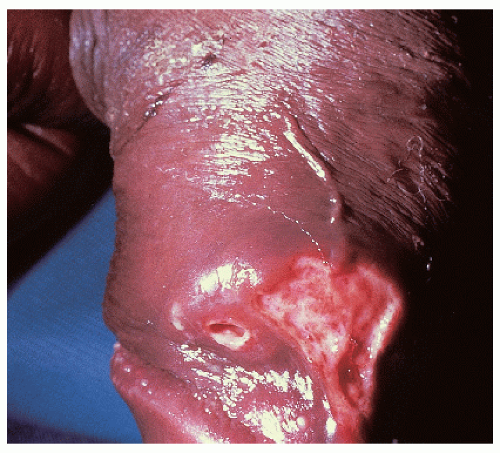

After an incubation period of 9 to 90 days (average of 3 weeks), the primary lesion occurs at the original site of inoculation. It begins as a small red papule that quickly enlarges and ulcerates to form a painless ulcer (“chancre”) that may be up to 2 cm in diameter. A chancre has a clean, red, glistening base (

Figs. 10-1 and

10-2). A small amount of nonpurulent, watery exudate may be present. The ulcer borders are sharply demarcated and are characteristically raised and indurated. The chancre is painless and usually nontender. The base feels firm on palpation. Most patients present with a solitary ulcer, but two or even multiple lesions are possible. Chancres are located most often at the distal tip of the penis in men and on the labia majora or vestibule in women. However, it is likely that many chancres in women are never observed due to a location within the vagina or on the cervix. For this reason, the first clinical presentation of syphilis in women is more likely to be at the secondary stage than is true for men. Individuals who have receptive anal intercourse may develop chancres within or around the anus. Secondary bacterial infection of ulcerative lesions may distort the clinical presentation, causing tenderness and purulent discharge. Within about 1 week of chancre formation in the anogenital area, unilateral or bilateral inguinal regional lymphadenopathy develops as nontender, firm, rubbery, mobile lymph nodes.

Diagnosis

The presence of a solitary, nontender ulcer with a clean, firm base is highly likely to represent primary syphilis. Nevertheless, a clinical diagnosis must be confirmed by laboratory means. In years past, the quickest confirmation could be obtained by a dark-field examination carried out on site by the clinician. Unfortunately, this test has almost completely disappeared due to the lack of dark field microscopes in clinicians’ offices and the declining skills in carrying out this test. For this reason, a serologic test for syphilis needs to be obtained. The most commonly used nontreponemal serologic tests are the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and the rapid plasma regain (RPR) tests, both of which detect antibodies to cardiolipin. These are readily available, cheap, and reliable. In addition, positive results can be titrated providing a valuable tool for determining response to

therapy. Unfortunately, there are several drawbacks to these tests: (1) the test may not become positive until 1 or 2 weeks after the chancre has appeared; (2) false-positive tests occur with some frequency; and (3) false-negative tests may occur due to the prozone phenomenon especially in those patients who are coinfected with HIV.

Because of these drawbacks, treponemal-specific tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed test (FTA-ABS), the

Treponemal pallidum particle agglutination test (TP-PA), the

T. pallidum hemagglutination assay (TP-HA), and Western blots are available. These tests offer nearly 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity. Interestingly, some large laboratories are reversing the algorithm and are using automated enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) for initial screening followed by a VDRL or RPR if positive results are obtained. This latter approach may offer some cost savings but can cause difficulties due to both occasional false-positive results with EIAs and the fact that unlike the nontreponemal tests, they may remain positive after previous effective treatment and thus cannot be used for determining a response to therapy (

4).

Both the nonspecific and the specific serologic tests can remain negative for 7 to 14 days after a chancre appears. In this situation, biopsy should be considered for any lesion that is clinically suspicious for syphilis. The histologic presence of numerous plasma cells would then be followed by the use of a silver stain (e.g., Warthin-Starry stain) to identify the presence of spirochetes. Patients with syphilis are likely to have been exposed to other sexually transmitted diseases. For this reason, patients should be examined and tested for other infections when a diagnosis of syphilis has been established.

The two main considerations in the list of differential diagnoses are aphthous ulcers and genital herpes (HSV) infection, especially when the latter occurs in an immunosuppressed individual. Genital herpes occurring in those who are immunosuppressed may present with fairly deep, persistent, and relatively less painful ulcers rather than the more typical, transient, painful erosions seen in immunocompetent persons. Individual aphthous ulcers (as occur in complex aphthosis and Behçet disease) are similar in appearance to a chancre but, in contrast, several ulcers are usually present, they are extremely painful, and they tend to occur mostly in adolescent women. Chancroid is vanishingly rare in Western countries and is associated with a crusted base along with considerable pain and tenderness. Anogenital ulcers occur with Crohn disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, and granuloma inguinale, but the morphology is different as is the histopathology.

PRIMARY SYPHILIS: |

Diagnosis |

One or two relatively painless genital ulcers

Ulcer base is clean without crust or eschar

Base of the ulcer is firm and nontender on palpation

Positive RPR or VDRL; confirmed by positive FTA-ABS

If serology is negative, repeat tests in 1 week or biopsy

|

Pathophysiology

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete,

Treponema pallidum. The level of contagion for syphilis is very high; it has been estimated that about one third of individuals having direct contact with a chancre will develop syphilis. The likelihood of infection is further enhanced in the presence of even minor breaks in the skin as well as in a setting of immunosuppression such as occurs with HIV infection (

5). The reverse is also true. There is an increased risk for the acquisition of HIV in patients with chancres. Many (

6), but not all (

7), studies suggest that circumcision in males reduces the likelihood of acquiring

syphilis. The incubation period after exposure to

T. pallidum is quite variable but averages about 3 weeks. Unfortunately, before the end of the incubation period and therefore before the development of a chancre, spirochetes have already gained access to the regional lymph nodes. For this reason, syphilis can be viewed as a systemic infection from its earliest inception.

Management

If untreated, a chancre undergoes spontaneous, nonscarring resolution within about 1 to 2 months. This leads the patient to the misconception that the process has healed and that it is not necessary to seek medical attention. However, as indicated above, syphilis becomes a systemic infection soon after the initial inoculation with the result that after a short latent period the generalized lesions of secondary syphilis are highly likely to appear. Rarely, secondary lesions may appear, without a latent period, while the chancre is still present. If the symptoms and signs of secondary syphilis are unrecognized and the patient remains untreated, the patient enters another latent period, leading some years later to the possibility of tertiary syphilis.

Most clinicians in the United States follow the treatment guidelines published by the CDC. The most recent update is from 2006 where benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units, administered intramuscularly in a single dose, is the recommended therapy for primary and secondary syphilis (

8). Note that Bicillin L-A (containing only benzathine penicillin) is to be used rather than Bicillin C-R that contains a combination of benzathine penicillin and the short-acting procaine penicillin. No penicillin resistance has yet been noted. Guidelines that are somewhat similar to those of the CDC have been developed for the United Kingdom and Europe (

9,

10). Because of their similarity, they will not be reviewed here.

For those who are allergic to penicillin, the CDC recommends desensitization rather than use of a second-line treatment with a nonpenicillin product. However, where desensitization is not feasible, it is appropriate to use alternative antibiotics such as doxycycline (100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days), ceftriaxone (1 g IM daily for 10 days), or azithromycin (2 g in a single oral dose) (

8). The CDC recommendation for desensitization stems from a relative lack of published experience with all three of these agents together with some reports of azithromycin resistance. Patients who are pregnant should be treated with penicillin. Limited evidence suggests that in HIV infected persons, the response to therapy may be somewhat diminished. For this reason, some clinicians choose to repeat the 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin weekly for 3 weeks.

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile reaction that may occur within 24 hours of treatment for syphilis, regardless of the treatment regimen used. Symptoms include headache, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, and fever. This transient reaction occurs most commonly after treatment for early syphilis and requires only reassurance, bed rest, and antipyretics for management.

Patients who are treated for primary or secondary syphilis require follow-up documentation of response. This is done by determining the titer of the RPR or VDRL antibodies at periodic intervals until at least a fourfold drop in titer has been obtained. Note that although either the RPR or the VDRL can be used, the same test must be used consistently as the titer levels differ between the two tests. Nearly all patients with early syphilis will eventually develop a negative RPR or VDRL test. However, this is not true for the treponemal specific tests (see above) where lifelong positivity usually continues.

PRIMARY SYPHILIS: |

Management |

Benzathine penicillin (Bicillin L-A) single dose 2.4 million units IM

Consider repeating the dose if the patient is HIV positive

Desensitize if the patient is allergic to penicillin

Or, doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. × 14 days, azithromycin 2 g as single dose

Follow RPR or VDRL titer until negative

|

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access