Tropical Diseases of the Skin

Francisco G. Bravo MD

Salim Mohanna MD

A chapter on tropical diseases is a must in this era of globalization. By tropical diseases, one may think of diseases limited to the tropical and subtropical areas of the world. The term actually implies the study of infectious diseases endemic to specific areas of the world, not always located in the tropics (i.e., human T-cell lymphotropic virus [HTLV]-1 in Japan). Once a domain of European doctors traveling to colonies in the 19th century, tropical disease now has implications for every specialty in medicine, including, of course, dermatology. Traveling, either for tourist, business, or military purposes or just as immigrants in search of a better future for their families, has expanded the limits of where diseases discussed in this chapter can be seen. Let’s keep an open mind and not forget to ask where the patient was born and where he or she is coming from.

Viral Diseases

HTLV-1

The HTLV-1 is a retrovirus of the subfamily Oncovirinae, with the ability to infect CD4 cells and induce different degrees of immunosuppression. An estimated 10 to 20 million persons are infected with the virus worldwide. There are multiple endemic areas in the world, in Africa (Gabon, Zaire, Ivory Coast), Asia (Japan, Iran), and Australia (the aborigines group). In the American continent its presence is well established in Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados, and Haiti. In South America, countries affected include Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. In the United States, Canada, and Europe, the incidence of seroprevalence is low, but when one looks at specific migratory populations, the number can increase dramatically.

The infection was disseminated to the Americas from three different sources: early migration of Mongoloid population to the American continent in ancient times, the trade of African slaves in the 19th century, and migration of the Japanese as a labor force in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Presentation and Characteristics

The most common routes of transmission are breast-feeding, sexual contact, and blood transfusions. As opposed to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (the other well-known retrovirus), most HTLV-1-infected patients will remain asymptomatic for the rest of their lives and no more that 5% will develop some clinical manifestations.

HTLV-1 infection can induce disease due to an altered immune system (infective dermatitis, crusted scabies, and disseminated dermatophyte infections), autoimmunity (tropical spastic paraparesis, uveitis), and neoplasia (leukemia/lymphoma). Most dermatologists may have heard of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, but, in fact, cutaneous disease due to immune dysfunction may be more common.

Infective dermatitis was first described in Jamaican children in 1966. Louis La Grenade described its relation to HTLV-1 infection in 1970. The clinical picture is that of a chronic, eczematous dermatitis affecting the scalp and intertriginous areas, such as the neck folds, axillae, and groin (Fig. 45-1). On the face it may follow a seborrheic dermatitis-like distribution. The main affected population is children, although the disease may be seen in adulthood. An important component is the constant degree of superinfection by Staphylococcus aureus and β-hemolytic Streptococcus. This condition can be described as an “oozing, honey-crusted seborrheic dermatitis or intertrigo,” as an “always

impetiginized scalp psoriasis,” or as “atopic dermatitis with predominant scalp involvement.” This is, in fact, a viral-induced dermatitis and a model for atopic dermatitis. Most patients with infective dermatitis clear when treated with antibiotics, but the disease recurs when the treatment is discontinued, adopting a chronic course. Many affected children will go into remission when reaching puberty, in a way similar to atopic patients. Some consider infective dermatitis a marker for a higher risk of developing lymphoma.

Crusted scabies have been described in populations that are known to be endemic for HTLV-1, such as Australian aborigines. Also, in places with high prevalence, like Lima and Peru, most cases are related to the retrovirus infection, even more commonly than immunosuppression secondary to HIV infection or chronic steroid therapy.

Pruritus, xerosis, and ichthyosis are considered by some researchers as the most common HTLV-1 manifestations, although they are not very specific.

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma was linked to HTLV-1 in the Japanese population in 1977 and is actually seen in all endemic areas. Between 25% and 40% of cases will have cutaneous involvement. Five subtypes have now been recognized including acute leukemia, chronic leukemia, lymphoma, smoldering, and a purely cutaneous form. The skin lesions may vary: a number of cases will be indistinguishable from mycosis fungoides and others will present with a more varied morphology including papules, nodules, tumors, and even erythroderma and ichthyosiform eruptions.

Dengue

Presentation and Characteristics

Dengue, or breakbone fever, is one of the most prevalent viral diseases in the world, causing a systemic illness expressed as a neurologic infection, an acute febrile disease with arthropathy, or a hemorrhagic fever. It is caused by an RNA flavivirus, with four described serotypes. It is present around the world (one hundred million cases per year), in tropical and subtropical areas of Africa and Asia, and it is also becoming an increasing public health problem for some countries in South and Central America.

The disease is transmitted by the bite of mosquitoes belonging to the genus Aedes, mainly A. aegypti, which is also a carrier of yellow fever. Dengue is present most commonly in urban areas with poor sanitary systems. The mosquitoes thrive whenever they find open water reservoirs. Aedes is also the main living reservoir for the virus.

The disease may adopt various clinical forms, from mild to classic to a more severe and dangerous hemorrhagic form, the so-called dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). Whereas the classical form is more common in new arrivals to endemic areas, the more severe DHF is more likely to affect children, residents of endemic areas, and those who have already had dengue in the past.

Clinical Appearance

The classical form starts as a sudden fever, lasting 2 to 5 days, and is associated with headache, intense myalgias and arthralgia, and retro-orbital pain. Cutaneous involvement varies, from facial flushing to a more diffuse macular or maculopapular morbilliform eruption. The erythematous areas become confluent, leaving small spared areas of normal skin, similar in a way to what is seen in pityriasis rubra pilaris, although lacking its roughness; this image is described as “white islands on a red sea” (Fig. 45-2). The main area of involvement is the trunk, with the eruption spreading centrifugally toward the extremities. Petechial eruptions affecting the lower extremities are also seen. Pruritus may be present, and a later state of desquamation may follow.

DHF presents with a more severe course, including vomiting, facial flushing, perioral cyanosis, and weakness with cool and clammy extremities. Hemorrhagic complications, such as gastrointestinal (GI) and genital bleeding, appear, and the patient may go into a dengue shock syndrome. This state may have a mortality rate as high as 10% if not given the appropriate support.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

These febrile diseases result from infection by viruses from these viral families: Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, Filoviridae, and Flaviviridae. Not all viruses in these families cause hemorrhagic fever. These viruses have a higher occurrence in tropical areas, such as South America, Africa, and the Pacific Islands. Clinical manifestations of hemorrhagic fever include capillary permeability, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Hemorrhagic fever is manifested by sudden onset, fever, headache, generalized myalgia, backache, petechiae, conjunctivitis, and severe prostration. Intensive supportive care is necessary for most cases of hemorrhagic fevers.

Bacterial Infections

Bartonellosis, Including Carrion’s Disease and Bacillary Angiomatosis

Until the AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) era, bartonellosis was one of those exotic diseases only studied for board examinations. The first description of Carrion’s disease was made at the beginning of the 20th century and came from endemic areas in the Peruvian Andes; the causal agent was identified as Bartonella bacilliformis. The bacteria, a gram-negative rod, was transmitted from the natural reservoirs to humans by the bite of mosquitoes belonging to the Lutzomyia family.

Presentation and Characteristics

The disease has two characteristic phases, one systemic and another purely cutaneous. The first phase, known as Oroya fever, produces an impressive bacteremia and parasitism of the reticuloendothelial system, in which microorganisms may be seen inside red blood cells on peripheral smears. The clinical picture is a systemic disease with fever, malaise, and high susceptibility to other bacterial infections, such as salmonellosis.

The most distinct and relevant phase for the dermatologist is the eruptive phase, known as verruga peruana. It may follow the bacteremia or it may present de novo. Characteristically, an eruption of multiple papules, nodules, and tumors appears over a period of weeks. The more superficial lesions have an angiomatous appearance, resembling pyogenic granulomas (Fig. 45-3). The natural course of the disease is toward spontaneous involution, although antibiotic treatment may induce a more prompt remission.

At the beginning of the 1980s, some patients with AIDS presented with a clinical picture very similar to the eruptive phase of verruga peruana. This new disease was named bacillary angiomatosis. The histologic descriptions of the eruptive lesions of bacillary angiomatosis were identical to those described in verruga peruana, which was the only bartonellosis known at the time. The initial thought was to associate this new entity with catscratch disease. At a later time, isolation of a gram-negative rod from the lesions led to classifying it under a new family of bacteria called Rochalimaea. Genetic studies demonstrated a close relation between Rochalimaeas and Bartonellas, resulting in a new grouping under the term Bartonella. The new species include B. henselae, B. quintana (both cause bacillary angiomatosis, catscratch fever, and systemic disease associated with fever), and B. elizabethae, which causes septicemia and endocarditis in alcoholics.

Bacillary angiomatosis is now recognized as a disease characteristic of immunosuppressed patients of all kinds, although it has been reported in immunocompetent patients. The most likely natural reservoir is domestic animals such as cats. It is cosmopolitan, as opposed to verruga peruana, which is still endemic to Andean areas of Peru and Ecuador.

Anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by Bacillus anthracis, an encapsulated gram-positive bacteria capable of surviving up to 20 years in dry grass. The disease is more common in people working with cattle. The infection is acquired either by contact through the skin or by inhalation of spores. The cutaneous lesion, called malignant pustule, is usually located in exposed areas of the skin, especially the face, neck, arms, or hands and is usually solitary. One to five days after the inoculation, a papule grows. A blister then forms on an edematous base that eventually breaks, leaving a hemorrhagic crust. Redness and edema may be very marked (Fig. 45-4). General symptoms appear on the third or fourth day; the condition may result in severe toxicity and even lead to death.

Treatment

Treatment options include penicillin, doxycycline, and quinolones.

Rhinoscleroma

Presentation and Characteristics

Rhinoscleroma, also known as scleroma, is a chronic disease of very slow progression that is potentially fatal. It is caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis (Frish bacillus). Three stages have been recognized:

The initial stage is that of rhinitis. The first symptoms are generally nasopharyngeal; the lesions grow slowly, and often the patient does not seek medical attention for years. This is an exudating stage, with symptoms similar to those of a common cold, including headache and difficulty in breathing. There is a very purulent, fetid secretion with crusts and occasional epistaxis.

The second stage is proliferative, characterized by obstruction and infiltration of nasal tissues by a friable granulomatous tissue. By extending into the pharynx and the larynx, it may cause hoarseness. Later, during a nodular period, the nose increases in size, adopting a “tapir” shape. Respiration becomes difficult, and it may be necessary to do a tracheotomy.

The third stage is fibrotic sclerosis (Fig. 45-5), and although associated with partial improvement and occasionally a spontaneous cure, it usually results in a marked distortion of the anatomic structures. Invasion of the bone and nasal sinuses, with eventual destruction of bone tissue may occur. The diagnosis is based on the clinical and histologic picture and the presence of the Frish bacillus.

Treatment

Treatment includes antibiotics such as tetracycline, azithromycin, cephalosporins, and trimethoprim. It does not respond to sulfa or penicillin. When using tetracycline, 2 g/d should be given for a period of 6 months.

Nonvenereal Treponematoses

Different species of the spirochete Treponema cause different infections in humans. T. pallidum causes venereal syphilis. T. carateum and T. pertenue cause pinta and yaws, respectively. Endemic syphilis or bejel is caused by T. pallidum endemicum.

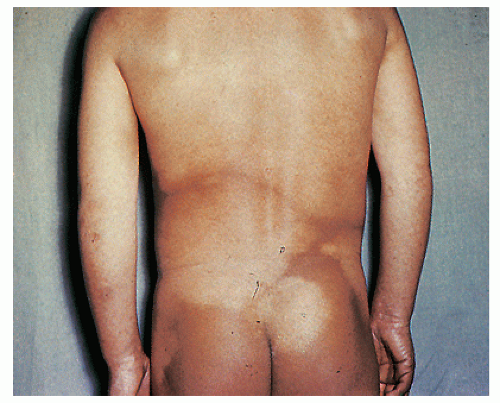

Pinta has been restricted to lowland tropical areas of Central and South America. Transmission occurs during childhood by direct contact with lesions from infected individuals, but it is not transmitted by sexual contact. Patients go through three different stages, with early, secondary, and late lesions. The primary lesion is an erythematous papule that becomes scaly, psoriasiform, and even liquefied. It is usually located on lower extremities and becomes dyschromic with time. Secondary lesions appear about 2 months after the primary lesion. They are multiple and similar to the primary lesion, although smaller. The most prominent change is again the dyschromia, with hyper/ hypopigmentation mixed in single lesions. The late lesions consist of extensive areas of hypopigmentation and achromia, resembling vitiligo (Fig. 45-6). Pinta should be suspected in patients from endemic areas with extensive dyschromias. Treatment is based on penicillin therapy. The changes in color do not reverse with antibiotic therapy.

Yaws, also called “pian” or “frambesia,” is a contagious, nonvenereal disease that mainly occurs in children younger than 15 years. It is endemic to all tropical areas around the world, from Central and South America, to Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands. The clinical manifestations go through the three classical stages of early, secondary, and late lesions. The primary lesion is a chancroid in appearance, whereas the secondary lesions are papillomatous verrucous, similar to condylomas. In skin they resemble raspberries, giving origin to the French name, “frambesia.” Bone involvement can be rather destructive, ending in severe deformities and mutilations. Tertiary lesions can be gumma-like and

achromic, as in pinta, and can produce palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Treatment is based on the use of penicillin.

achromic, as in pinta, and can produce palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Treatment is based on the use of penicillin.

Bejel is still reported in the Middle East, the African Sahara, and some areas of the tropical belt. Like yaws, it is a disease of infants and children. The clinical manifestations are similar to the mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis, with a condylomatous appearance. Tertiary lesions are similar to yaws.

Mycobacterial Infections

Tuberculosis and leprosy are diseases caused by mycobacteria. They are discussed in Chapter 21.

Mycobacterium marinum Infection (Swimming Pool Granulomas)

Mycobacterium marinum (formerly called Mycobacteria balnei) infection is characterized by the presence of an indolent verrucous papule that later evolves into a plaque or a nodule with central scarring that may eventually ulcerate.

Presentation and Characteristics

It is commonly located on the extremities, especially at points of trauma (hands, elbows) that are in contact with fresh water, salt water, or marine animals such as fish or turtles. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 6 weeks. Patients may present with a papule or nodule that subsequently ulcerates (Fig. 45-7). The lesion is usually solitary, and there is no systemic reaction. Satellite lesions may appear and may simulate a localized granuloma or sporotrichotic lymphangitis. Both visualization of the bacteria on skin tissue and its isolation by culture are rather difficult.

Treatment

Minocycline seems to be the drug of choice. Alternatives drugs include rifampin plus ethambutol, tetracyclines, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, clarithromycin, and fluoroquinolones. The duration of therapy is empiric, with recommendations to continue therapy for several weeks following clinical resolution of lesions. Surgical excision, or thermal therapy, has been employed with relative success.

Mycobacterium ulcerans Infection (Buruli Ulcer)

This mycobacterial infection was first described in southern Australia as Bairnsdale ulcer and later in Africa (from the Buruli valley in Uganda) and South America. In west and central Africa, it is considered a public health problem. This is, in fact, the third most common worldwide mycobacterium infection in immunocompetent patients, after only tuberculosis and leprosy.

Presentation and Characteristics

The bacteria lives in the environment and is acquired by humans through contamination of traumatic wounds. The classical clinical presentation is an ulcer, located most commonly on extremities. The cavity extends laterally, undermining the edges of the lesion, so the defect is always larger than what is seen at first glance. The ulceration will continue to enlarge and produce marked destruction and mutilation of the affected areas. The morbidity of the disease is directly related to the skin lesion, with no systemic disease.

On histology, the pattern is of massive necrosis of fatty tissue. With stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen, a huge amount of bacteria is seen in the necrotic areas, in quantities only comparable to lepromatous leprosy. The necrosis is a direct effect of a bacterial toxin, mycolactone, which is a soluble polyketide.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical and histologic findings. The bacteria are difficult to isolate, although it can be done on special mycobacterial media. New diagnostic techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) will allow early diagnosis in smaller lesions. Surgical excision of the whole necrotic area is considered the treatment of choice.

Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria (Mycobacterium fortuitum group)

This group includes a series of microorganisms causing chronic infections after traumatic surgical, cosmetic, or therapeutic inoculation. A growing number of cases are being reported in South America and around the world as late complications of liposuction or mesotherapy. Mycobacterium species implicated include M. fortuitum, M. abscessus, and M. chelonae.

Presentation and Characteristics

Patients present with cold abscesses at the site of trauma, injection, or surgery, weeks to months after the precipitating event (Fig. 45-8). Upon draining, a purulent fluid may be obtained. Direct examination shows the presence of acid-fast staining bacilli. Unless treated, the lesion becomes chronic, with fistula formation and progressive infiltration of surrounding tissues. Although these groups of bacteria are

called rapid growers, their isolation requires special media and low temperatures. M. abscessus is able to grow for more than a year in distilled water; contamination of surgical material or injectable substances is considered a potential source of infection when dealing with epidemic outbreaks.

called rapid growers, their isolation requires special media and low temperatures. M. abscessus is able to grow for more than a year in distilled water; contamination of surgical material or injectable substances is considered a potential source of infection when dealing with epidemic outbreaks.

Treatment

Treatments of choice include clarithromycin and quinolones. Amikacin can be used in deep-seated infections

Parasitic Diseases

Protozoal Dermatosis

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is an infectious process caused by intracellular parasites of the Leishmania genus. The disease is transmitted from natural reservoirs to humans by mosquito bites.

Presentation and Characteristics. The different forms of cutaneous disease are produced by species of Leishmania specific for certain regions in the world, like those seen in the Middle East (L. tropica), Central America (L. mexicana), and South America (L. peruviana and L. braziliensis). There is even an endemic area of leishmaniasis in the state of Texas. Different names are given to the disease depending on the geographical location: Oriental sore in Asia, Chiclero’s ulcer in Mexico, Uta in the Andes, and Espundia in the Amazon basin.

The classical cutaneous lesion consists of a round, isolated ulceration, with slightly elevated and indurated borders (Fig. 45-9). Common locations are areas of the body not covered by clothing and therefore exposed to the mosquito bite such as the face, neck, and extremities. The lesion itself is painless and tends to regress spontaneously.

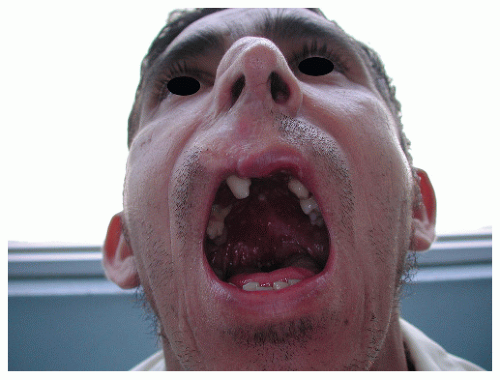

The variety known as mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which is cased by L. braziliensis, is characterized by its ability to produce, after a dormant period, an ulceration on the mucosae of the nasal septum. This can progress externally, mutilating the whole nose and nasolabial area (Fig. 45-10). When the progression is on the mucosal side, it may destroy the palate, producing a granulomatous infiltration of the pharynx, the larynx, and even the upper respiratory airway.

The tissue destruction seen in leishmaniasis is in fact a result of the great inflammatory reaction induced by the parasite, rather than the virulent effect of the microorganism

itself. In an early lesion, a heavy infiltration of histiocytes, many of them engulfing the Leishmania

itself. In an early lesion, a heavy infiltration of histiocytes, many of them engulfing the Leishmania

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree