Disorder |

Cutaneous Findings |

Associated Malignancies |

Acanthosis nigricans |

Velvety hyperpigmentation of flexures and, less commonly, mucosal surfaces and palms (tripe palms) |

Adenocarcinoma of genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract. Most commonly associated with adenocarcinoma of the stomach (55.5%)* |

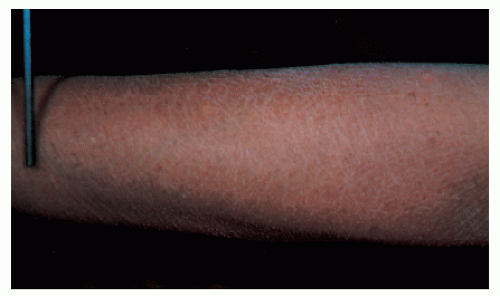

Acquired ichthyosis |

Adult onset hyperkeratosis indistinguishable from ichthyosis vulgaris |

Hodgkin’s lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, multiple myeloma, leiomyosarcoma |

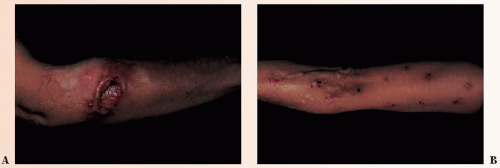

Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) |

Acral psoriasiform plaques with nail dystrophy |

Carcinomas of upper digestive and respiratory tracts. Also described in association with transitional cell bladder carcinoma† |

Carcinoid syndrome |

Deeply erythematous or violaceous flushing of upper body associated with pruritus, diaphoresis, lacrimation, and facial edema |

Foregut, midgut, and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors |

Cushing’s syndrome |

Generalized hyperpigmentation, including areolae, palmar creases, and scars; hirsutism; central obesity; moon facies, striae |

Ectopic ACTH production by small cell lung cancer, bronchial carcinoid tumors and cancers of the thyroid, pancreas, and adrenals |

Dermatomyositis |

Heliotrope dermatitis, proximal nail fold telangiectasias, Gottron’s papules, cutaneous necrosis |

Ovarian, gastrointestinal, and nasopharyngeal carcinomas; adenocarcinomas of the lung and prostate; hematologic malignancies |

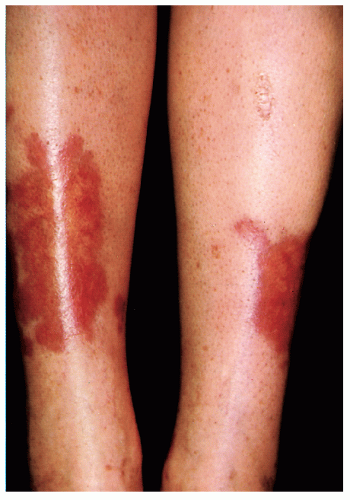

Erythema gyratum repens |

Migratory figurate erythema with “wood grain” pattern |

Malignancies of the lung, breast, female reproductive tract, gastrointestinal tract, and prostate |

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa acquisita |

Excessive growth of vellus hairs on neck and face, but can involve any body surface |

Most commonly observed with colorectal, breast, and lung cancers |

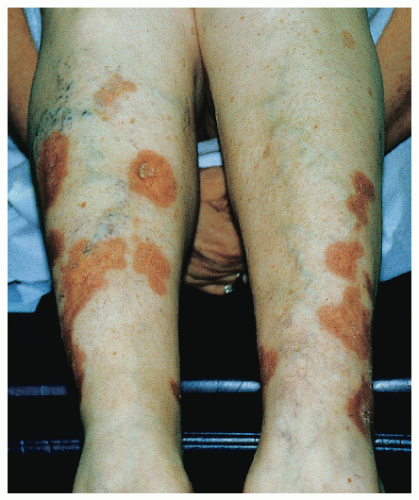

Necrolytic migratory erythema |

Acral and intertriginous papulosquamous dermatitis with occasional vesiculation |

Pancreatic α-cell tumor presents with glucagonoma syndrome |

Paget’s disease |

(1) Unilateral eczematous nipple plaque (2) Eczematous plaque of the anorectal, genital, and axillary regions (extramammary Paget’s disease) |

(1) Associated with ductal adenocarcinoma (2) Regional associations are (a) anorectal—adenocarcinoma of the anus and colorectum, (b) vulvar—epithelial, eccrine, and apocrine neoplasms, and (c) male genitourinary reproductive tract malignancies |

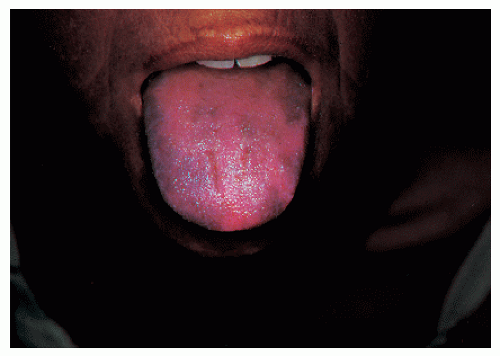

Paraneoplastic pemphigus |

Diffuse mucocutaneous involvement with blisters, erosions, lichenoid, and erythema multiforme-like lesions. Head and neck skin is usually spared. Extensive oral erosions are notable. |

Hematologic malignancies |

Porphyria cutanea tarda |

Vesicles and bullae with subsequent scarring, skin fragility on the dorsal hands, milia formation, and hypertrichosis on sun-exposed surfaces |

Hepatocellular carcinoma, hematologic malignancies, myelodysplastic syndromes |

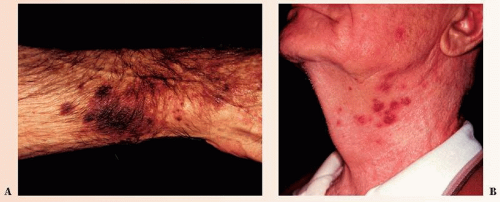

Sweet’s syndrome—atypical bullous pyoderma gangrenosum overlap |

Indurated erythematous to violaceous plaques with or without bulla formation and ulceration |

Hematologic malignancies, myeloproliferative disorders |

Sign of Leser-Trélat |

Eruptive multiple seborrheic keratoses |

Adenocarcinomas of the lung and gastrointestinal tract |

* From Rigel DS, Jacobs MI. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6(11):923-927.

† From Arregui MA, Raton JA, Landa N, et al. Bazex’s syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica)—first case report of association with a bladder carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18(5):445-448. |

Abbreviations: ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone. |