Sports Medicine Dermatology

Rodney S.W. Basler MD

Parallel to the burgeoning interest of the general population in establishing personal fitness programs, sports-related conditions of the skin resulting from injury, infection, and exacerbation of preexisting dermatosis are presenting with increasing frequency in the offices of dermatologists across the country. In addition, athletes at all levels of competition from junior high school through professional sports are in need of the services of dermatologic practitioners who are well-informed in this subset of cutaneous problems. By classifying the various categories of dermatologic issues related to sports medicine into these groupings, a problem-oriented approach to dermatology and sports medicine emerges that will enable the clinician to evaluate these problems in a direct organized manner (Table 46-1).

Athletic Injuries

The integument, positioned at the interface between the athlete and the sporting environment, experiences disruption both from acute and long-term application of sports-related external forces. Preventing these injuries, or treating them aggressively to bring about an immediate resolution, greatly enhances a participant’s ability to quickly return to workouts and competition.

Friction Injuries

Abrasions

Presentation and Characteristics. Abrasions occur when the granular and keratinized cells of the outer layers of skin are abruptly removed from the underlying dermis or “true skin.” This trauma exposes the lower papillary and reticular dermis, causing punctate bleeding from the severed arterials of the dermal papilla. These pinpoint areas of bleeding within a larger patch of tissue exudate produce the appearance of a lesion referred to in the vernacular as a “raspberry” or “strawberry.”

Treatment. The treatment of acute abrasions, as with all other forms of injury, is determined by its severity. Minor abrasions can be treated by gentle cleansing with a mild detergent or soapless cleanser such as Cetaphil antibacterial bar. A trick used by many trainers is to have a can of mentholated shaving gel in their treatment kit, which also works well for cleansing minor lesions and precludes the need for having clean water on the sideline, although the latter is usually present for preventing dehydration. Bacitracin ointment and a dry dressing can then be applied.

TABLE 46-1 ▪ Classification of Dermatologic Issues Related to Sports Medicine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This provides a moist environment promoting healing with a minimum of scarring. Larger abrasions, especially those that have been contaminated by the environment, require more aggressive immediate care. Treatments must minimize additional trauma, and aggressive scrubbing, especially with cleansers such as hydrogen peroxide or povidone iodine (which may be cytotoxic), should be avoided. A large “pistol-type” or plunger syringe should be used to irrigate the lesion. Nontoxic surfactant cleansers are the wash of choice.

Proper cleansing is followed by the application of a hydrocolloid or semiocclusive hydrogel dressing that provides a moist healing environment allowing for epithelial migration and prevents the formation of crust or eschar (Fig. 46-1) These artificial barriers can remain in place for 5 to 7 days, and may be covered with padding and tape to allow for continued participation in practice or competition.

Prevention. Preventing abrasions requires little more than a commonsense approach to protecting skin potentially exposed to acute trauma. Areas at risk should be covered with protective equipment such as sliding pads, long-sleeved shirts, long socks, “biker” shorts, or a self-adhesive bandage such as Coban.

Turf Burn

Presentation and Characteristics. Turf burn is a related injury that develops when an athlete, most commonly a football or soccer player, has an exposed area of skin slide across artificial turf. Interestingly, the injury is also seen, with some frequency in an ancillary group of athletes, particularly at a collegiate or professional level, namely cheerleaders. As the name implies, the injury results as much from the generation of heat in the skin as from friction, producing an injury that is part abrasion and part burn; artificial turf has a lower coefficient of friction than natural grass, especially when wet.

Treatment. Because the injury is not as deep as seen with most acute traumatic abrasions, treatment can be less aggressive with cleansing of the area and the application of an antibiotic ointment such as mupirocin or silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene).

Prevention. As with other forms of abrasion, turf burns are best prevented by having specialized equipment, athletic tape, or Coban applied to areas of potential injury.

Chronic Friction Injury

Calluses

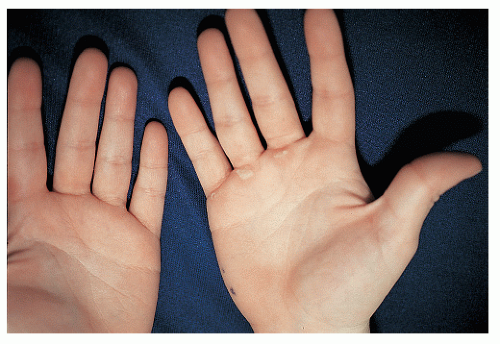

Presentation and Characteristics. Calluses present as thick hypertrophied stratum corneum without the characteristic puncta noted with clavi or “hard corns.” They represent a compensatory protective response that forms a keratin shield between the outer layers of the skin and an article of equipment, by far the most common being athletic shoes. There often is a history or recently appearing clinical evidence of an anatomic defect underlying the callus. Significant calluses also may be observed on the palmar surface of the hands of golfers, oarsmen, tennis players (Fig. 46-2), and gymnasts. The latter usually consider calluses to be a competitive advantage, and for that reason, generally do not treat them.

Treatment. Because calluses often represent a protective mechanism of the skin, treatment is usually not necessary. The main reason to approach the lesions is to prevent the formation of painful blisters near the edges of the calluses. Careful paring, usually after soaking, followed by smoothing with a pumice stone or file, usually eliminates the calluses.

Prevention. To a certain extent, calluses are not preventable, and there is no particular reason for concern, unless they interfere with athletic performance or blister formation is a problem. Modification of footwear and the addition of gloves for tennis players and weightlifters are sometimes helpful.

Blisters

Presentation and Characteristics. The appearance of a tender vesicle or bullae, sometimes tinged with blood, over the site of the application of applied force does not usually represent a diagnostic quandary (Fig. 46-3). Unfortunately, especially when unroofed, these lesions cause significant pain and tenderness to the athlete, and may seriously curtail the length or level of competitive activity. During a recent playing of the US Open tennis tournament, it was noted that more participants visited the first aid tent for skin-related problems than for all other injuries combined, and the great majority of the problems were blisters.

Treatment. As with most injuries, treatment depends on the size and location of the blister. Small blisters are usually self-limiting and respond to conservative management. It has been shown that the optimal approach to the epidermal “roof” is to leave it intact when possible. The blister should be drained three times at 12-hour intervals for the first 24 hours by using a flamed needle or scalpel. The blister is then covered with a hydrocolloid membrane or tape, either of which can be left in place for 5 to 7 days, allowing for repair of the epithelim.

Prevention. In general, to help prevent blisters, athletes should increase the length and intensity of exercise workouts gradually, especially when breaking in new shoes or rackets. Early studies in the military proved, unequivocally, that moisture is a major contributory factor, and needs to be minimized, especially over the feet. Newer acrylic-composition socks are designed to wick perspiration from the skin at the same time that they diminish friction and should be changed every 30 to 60 minutes if they become drenched in sweat. Some athletes also find the application of petroleum jelly or Aquaphor over pressure points to be of considerable benefit.

Chafing

Presentation and Characteristics. Chafing is produced by the mechanical friction between the skin covering two apposing body parts or between the skin and an article of clothing. It is a common problem, familiar to participants of nearly all sports, and presents as bright red, inflamed, abraded patches that are sensitive to the touch. In extreme cases, bleeding may be noted from the area of involvement. Although it is annoying and distracting, the condition usually does not lead to cessation of play. The upper inner thighs and axillae represent the most common distribution, and excess muscle or fat may contribute to the problem.

Treatment. The application of both a lubricating ointment such as triple antibiotic and Aquaphor relieves the symptoms and helps prevent further friction injury.

Prevention. Merely changing the athletic clothing to a fabric that generates less friction may bring about very significant improvement. Any adjustment in the area of involvement that eliminates or diminishes the friction applied to the skin surface ameliorates chafing. As already mentioned, the application of petrolatum or Aquaphor may be very helpful. To decrease moisture, which may play a causative role, some athletes favor absorbent powders.

Jogger’s Nipples

Presentation and Characteristics. A painful problem caused by long-term friction applied to a specific body part is the erosions that occur over the areolae and nipples of certain athletes. In extreme cases, the resulting injury may even cause hemorrhage into the clothing or uniform covering the area of involvement. Because the condition is particularly common in long-distance runners, it is usually referred to as jogger’s nipples. Because most women athletes wear some type of soft protective sports bra, the problem is more common among men than women.

Treatment. Treatment is essentially the same as for all forms of superficial abrasion. The application of an antibiotic ointment covered by a simple dressing such as a Band-Aid is usually sufficient.