Pediatric Genital Disease

Libby Edwards

Genital complaints produce anxiety in patients generally, with fears of malignancy, sexual functioning, fertility, and sexually transmitted diseases. Genital symptoms and abnormalities in children are fraught with even more anxiety in parents, who feel responsibility for their child’s disease, while being unable to alleviate it. Often, providers have investigated the possibility of sexually transmitted disease, or have broached the subject of sexual abuse, producing even more anxiety, defensiveness, and anger. Or, a parent’s overattention to the child’s symptoms can lead to either anxiety on the part of the child or enjoyment of the attention with subsequent manipulation.

The primary therapy for parents of children with genital complaints is reassurance, and words of caution regarding information they will find on the Internet. Printed handouts are supportive, as the written word is perceived as authoritative, and assures the parent that the problem is one recognized and shared by others. Their child is not alone, and both information and treatment of the condition are available. Specific reassurance that their condition is not the parent’s fault, and that it will not affect fertility, sexual functioning, or the development of malignancy is crucial to many families.

NORMAL GENITALIA

The appearance of the prepuberal external genitalia varies with the age of the child and with the normal differences among individuals. Generally, clinicians do not examine the genitalia carefully after the newborn examination unless there are questions of abuse or disease. Therefore, the range of normal is often not appreciated, and, except for the hymen, there is little information on the normal variants and changes in the external genitalia.

Females

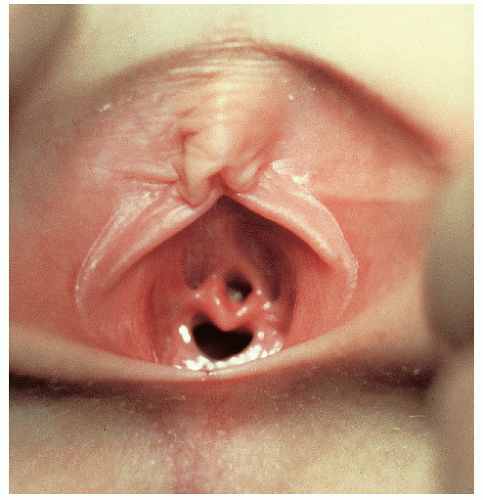

Newborn female genitalia reflect the effects of maternal hormones (Fig. 14-1). The presence of estrogen produces generous labia minora, which extend beyond puffy labia majora. The mucosa is pink, resilient, and moist, with thick hymenal folds covering the small vaginal and urethral openings. Milky, physiologic secretions are often present.

By 8 weeks of life, the effect of maternal hormones has diminished. The labia majora lose the full, puffy appearance, and the underlying labia minora and hymen are thin and flat. The labia minora are vestigial, and generally represent only anterior remnants of the clitoral frenulum. The vaginal opening is easily viewed, without a need for separation of the labia minora. The thin hymenal ring is present within the vaginal opening. There are several normal variations of the appearance and shape of the hymen. The mucosa is now thin and atrophic, often with a red and irritated appearance that worries parents. Friction, urine, stool, over-washing, soaps, etc. produce irritation in this atrophic, fragile skin. Tissues lack elasticity in early childhood, and this contributes to tearing with trauma. I believe that many children also experience adhesions of the clitoral hood to the clitoris simply as a result of this mild vulvar irritation, just as midline labial adhesions occur. Both processes generally reverse in later childhood. However, a recent study has reported that a third of college women exhibit synechiae of variable severity of the clitoris to the clitoral hood (1).

With the onset of puberty, there is thickening of all vulvar and vaginal tissues, and midline hair growth is noted. The labia majora become puffy with fat deposition, and the labia minora develop a rounded, thickened appearance. The clitoris enlarges, and the hymen thickens with enlargement of the central opening. As in infancy, the mucosa becomes pink, soft, elastic, and moist. White discharge is common as endogenous estrogens stimulate vaginal secretions, and puritus occurs in some girls as a result of the constant and unaccustomed wetness.

Males

The influence of maternal hormones on male genitalia is less pronounced. Newborn boys often exhibit swelling of the scrotum resulting from fluid collection in the tunica vaginalis during the birthing process or a hydrocele (see section “Hydrocele”). Hyperpigmentation of the scrotum and penile shaft may be more prominent at birth, especially in darkly pigmented races. A study of 10,421 newborns showed that all exhibited at least partial phimosis, with an inability to retract the foreskin (2). By adolescence, only 6.8% of boys could not retract the foreskin.

Before puberty, the penis is short and thin (Fig. 14-2). Pigmentation is similar to the general body pigment. The scrotum is less pendulous, and the skin is soft, thin, and pink, with few rugae. Both testes are palpable as soft masses within the scrotal sac. Small milia may be present on the scrotum.

At puberty, there is enlargement of the phallus both in length and circumference, with thickening and development of the glans. The scrotal sac and testes also enlarge and become more pendulous. The skin of the scrotum darkens and thickens, developing a coarse texture and folding into rugae. Pubic hair is noted first along the base of the shaft and then extending into the inguinal creases and onto the medial thighs as it becomes darker, coarser, and curlier.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

Hypospadias and Chordee

Hypospadias is a developmental anomaly in which the opening of the urethra is abnormally positioned on the undersurface of the penis. It can also occur in girls, with the urethral canal opening into the vagina. About 1 in 500 newborns are affected with hypospadias.

Hypospadias can be mild, with the urethral meatus opening on the ventral aspect of the glans, or more severe, with a larger opening more proximally on the shaft (Fig. 14-3). When the opening occurs at the penoscrotal junction, the penis is curved ventrally (chordee), and the penile urethra is very short. In the most extreme cases of hypospadias, the urethra opens into the perineum, the scrotum is bifid, and the chordee is extreme.

Testes are undescended in 10% of boys with hypospadias, and there may be an associated inguinal hernia, but other anomalies of the genitourinary tract are rare. However, severe cases of hypospadias can be confused with ambiguous genitalia, especially masculinization of female infants as a result of congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

FIG. 14-3. Hypospadias with the urethral opening at the penoscrotal junction. The penis is curved ventrally (chordee). |

Treatment for hypospadias and chordee is surgical and usually takes place in the first year of life. Mild cases are repaired for cosmetic reasons and to allow the child to void in a standing position. However, repair of severe hypospadias and chordee is essential to allow for normal sexual function. Newborns with hypospadias should not be circumcised because the foreskin will be used for the reconstructive procedure.

Hydrocele

A congenital hydrocele is a collection of fluid in the scrotum surrounding the testes (Fig. 14-4). It occurs when the processus vaginalis remains patent, connecting the abdominal cavity to the tunica vaginalis in the scrotum. If the connection is narrow, only peritoneal fluid collects in the tunica vaginalis, causing scrotal swelling and making the testis difficult to palpate. If it is large, a loop of intestine or the omentum can enter the processus vaginalis, forming an inguinal hernia. When the herniated viscera extend into the scrotum, a complete indirect inguinal hernia is present. Scrotal swelling resulting from a hydrocele can be distinguished from an inguinal hernia by transillumination of the scrotum; the former transilluminates brightly but the latter does not.

Small hydroceles often disappear in the first year of life. If the amount of fluid in the scrotum varies with time, a patent processus vaginalis with connection to the peritoneal cavity is present. This requires surgical correction, which is usually accomplished in the first year of life. Larger hydroceles that do not vary in size often require surgical correction as well.

Ambiguous Genitalia

Either virilization of the female fetus or incomplete virilization of the male fetus in utero produce ambiguous genitalia (Fig. 14-5). There are several different abnormalities that can lead to these developmental anomalies.

Clinical Presentation

Female infants are born as pseudohermaphrodites with varying degrees of masculinization. Enlargement of the clitoris and labial fusion are usual. Sometimes, the clitoris can be so enlarged that it resembles a penis. The urethral opening below is attributed to hypospadias, with cryptorchidism resulting in incorrect gender assignment. In boys, newborns are either phenotypically female or have varying degrees of virilization from labioscrotal fusion to perineal hypospadias and cryptorchidism.

Diagnosis

The identification of ambiguous genitalia is made on the clinical examination, but the diagnosis of the underlying cause requires laboratory testing, and is discussed in section “Management.”

Pathophysiology

The most common cause of female virilization is congenital adrenal hyperplasia. In this condition, there is an inherited enzymatic defect in the production of cortisol, usually resulting from a 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Deficiency of cortisol results in an increased secretion of corticotropin and stimulation of adrenocortical hyperplasia with overproduction of intermediate metabolites in the cortisol pathway. In the classic form of the disease,

patients are also salt losers, a potentially life-threatening condition when not recognized. Four other enzymatic defects of cortisone production as well as virilizing adrenocortical tumors in the mother can also result in ambiguous genitalia in the newborn female.

patients are also salt losers, a potentially life-threatening condition when not recognized. Four other enzymatic defects of cortisone production as well as virilizing adrenocortical tumors in the mother can also result in ambiguous genitalia in the newborn female.

In the male fetus, the situation is even more complex. Male pseudohermaphroditism can result from chromosomal deletion of the male-determining genes that are present on both arms of the Y chromosome, from aplasia or hypoplasia of Leydigs cells, from genetic defects in the synthesis of testosterone or in the production of other androgens such as dihydrotestosterone, or from peripheral cellular resistance to the action of these hormones.

Management

Ambiguous genitalia in a newborn should be addressed immediately. Chromosomal analysis should be undertaken at once. For female patients, studies of adrenal hormones should be done to rule out salt-losing adrenogenital syndrome. Ultrasound of internal organs to determine the presence of uterus and ovaries is indicated, as well as endoscopic examination of the vagina if possible.

For male patients, it is necessary to determine whether testicular androgen production is normal and whether there is normal conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. If a microphallus is present, it may be possible to stimulate growth with testosterone injection. If this is unsuccessful, boys are usually raised as girls. Gender assignment should take place early to avoid psychologic problems. Reconstruction of the external genitalia to create a functional female is more easily accomplished than creating a functional male phallus. Male testes are removed during surgery because of the increased incidence of gonadal malignancy in pseudohermaphrodites.

Labial Adhesions

Clinical Presentation

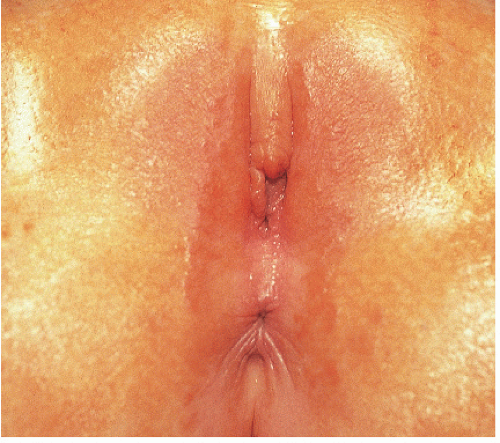

Labial adhesions appear as midline fusion of the introitus. This is the most common form of vaginal obstruction seen in prepubertal girls. Adhesions are posterior in 79% to 93% of affected girls (Fig. 14-6), sometimes with mid-or anterior adhesions forming (3). Uncommonly, the vulvar vestibule fuses entirely, covering the urethra (Fig. 14-7). Patients with labial agglutination are asymptomatic unless urinary retention or infection occurs behind the adhesions. Occasionally, even incomplete adhesions are bothersome as urine can become partially trapped above the synechiae, with dribbling when the child stands.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by the clinical appearance. The smooth, flat surface that overlies the introitus can suggest absence of the vagina, but it is distinguished by the presence of a central thin translucent line of fibrous tissue at the site of fusion.

Pathophysiology

Synechiae caused by chronic inflammation of the vulvar skin, resulting from mechanical trauma, infection, or skin disease, including lichen sclerosus or irritant dermatitis. Some have suggested that, because topical estrogen generally lyses labial adhesions, low estrogen levels may play a role in the formation of these adhesions. However, serum levels of estrogen in girls with labial adhesions are the same as those in girls without adhesions (4). Still, the normal infantile estrogen-deficient (compared to postpubertal girls) vulvar epithelium is thin, easily irritated, and more likely to scar compared to wellestrogenized vulvar skin. Vulvar epithelium scars easily in general, and even more so in atrophic prepubertal skin.

Management

Generally, no treatment beyond robust reassurance is required, as adhesions regularly resolve by puberty. Complete or symptomatic adhesions are treated with local application of estrogen cream combined with gentle massage and good hygiene, or a topical corticosteroid, especially if there is clinical underlying skin disease. Although the classic treatment is a topical estrogen, a recent retrospective chart review showed that a potent topical corticosteroid produced lysis of adhesions in an average of 1.3 months, with a lower recurrence rate, as compared to 2.2 months with the use of estrogen. Side effects with the estrogen were vaginal bleeding and breast budding, as compared to local irritation with the corticosteroid (5). Another chart review reported successful lysis of adhesions in 15 of 43 children treated with topical estrogen, with 19 lost to followup (6), and a third chart review of children treated with topical estrogen showed success in 79% of children, but 41% experienced recurrence of labial adhesions (7). A retrospective survey of girls treated with a potent topical corticosteroid showed success in 68% of children (8). A topical potent corticosteroid ointment (such as clobetasol or betamethasone dipropionate) is applied very sparingly once or twice a day, with monthly followup.

Occasionally, surgical separation is required because of pain, infection, or urinary retention. In a cooperative child, this can be done using topical anesthesia with lidocaine/prilocaine; the frightened child is best treated under general anesthesia/conscious sedation. A well-lubricated cotton swab sometimes can be used to separate the labia. More difficult scarring can be separated by peeling the synechiae apart following a nick of the edge of the line of fusion with a #15 blade. Estrogen cream or a corticosteroid ointment should be applied afterward to prevent reformation of the adhesions that is otherwise likely to occur immediately. The area should be re-evaluated every few days initially by the clinician to detect early recurrence during healing.

RED PLAQUES AND PAPULES

Diaper Dermatitis (napkin dermatitis)

Diaper dermatitis is best viewed as a combination of dermatoses that result from the unique environment of the diaper area. Diaper dermatitis must be differentiated from other skin diseases that preferentially occur in this area.

FIG. 14-8. Irritant diaper dermatitis with relative sparing of the inguinal creases (arrow), and papules on the convex surfaces of the mons and thighs. |

Clinical Presentation

Diaper dermatitis is characterized by scaling, erythematous plaques that sometimes exhibit maceration and erosion when severe. Often, there are several factors that produce this occluded dermatitis, and the features depend on the causes playing a role in that child.

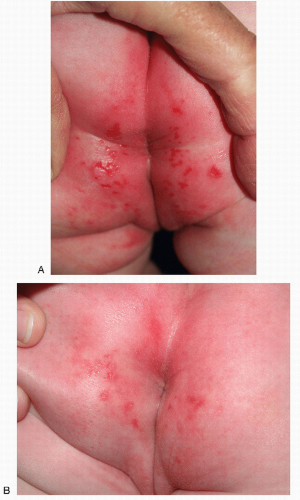

Irritant diaper dermatitis is characterized by dermatitis occurring on the more convex surfaces that directly contact urine and stool, and sparing of the skin creases (Figs. 14-8 and 14-9). The perineum, buttocks, lower abdomen, and upper thighs are most commonly involved. Sharp margination where the diaper ends is typical. The skin is pink to bright red, often with edema and superficial erosions that produce a shiny, glazed appearance. Eroded skin is tender and painful, especially when it is in contact with irritating substances such as alcohol or propylene glycol that are contained in diaper wipes.

FIG. 14-9. Irritant diaper dermatitis with shiny, glazed buttocks, fissures, and erosions that are covered with superficial erosions. |

FIG. 14-10. Jacquet dermatitis is severe irritant diaper dermatitis with characteristic eroded nodules; early changes of this condition are evident here. |

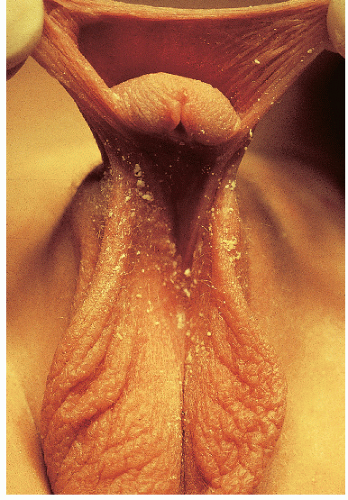

A severe form of irritant dermatitis is termed diaper dermatitis of Jacquet, granuloma gluteale infantum, or pseudowarts (see section “Granuloma Gluteale Infantum”). This is characterized by sharply marginated, red nodules, often with overlying erosion that confers an umbilicated appearance. These typically affect the labia majora, perianal skin, and the glans penis (Figs. 14-10 and 14-11). Crusting of the urinary meatus can make voiding difficult and painful.

Frictional dermatitis is most pronounced on the inner thighs, under the fastening tabs and waistband of the diaper, and on other surfaces that rub against the diaper. It consists of mild erythema and papules that wax and wane and respond quickly to diapering more often so that moisture is minimized.

Intertrigo from moisture and friction occurs within the skin folds of the diaper area, but also can occur in the neck creases, under the axilla, and between the fat rolls on the thighs. A sharp cutoff where the dry skin begins is noted. Affected areas are oozing, macerated, and red. Superficial sloughing of white hydrated skin is common.

When Candida albicans complicates diaper dermatitis, the infection preferentially affects the skin folds, with deep, bright erythema showing surrounding peripheral scale (Fig. 14-12). Satellite collarettes or round erosions are characteristic.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of diaper dermatitis is made by the presence of erythema and scale, with or without erosions and maceration in the diaper area. Specific dermatoses other than irritant dermatitis and candidiasis should be excluded. A biopsy is not indicated, but a fungal preparation of affected skin can help to elucidate the role of C. albicans.

Response to therapy helps to confirm the diagnosis. Any diaper rash that is properly managed with barriers, frequent diaper changes, low-potency corticosteroids, and antifungal agents should resolve over 1 to 2 weeks.

An inflammatory disease that occurs in the diaper area and resembles diaper dermatitis is psoriasis. Silvery scale in drier areas and sharply demarcated borders suggest this diagnosis. Often, typical plaques on other skin surfaces and nail changes support a diagnosis of psoriasis. Seborrhea mimics diaper dermatitis, but these babies have scalp disease as well. The presence of lichenification suggests atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis of the diaper area is generally accompanied by pruritic eczematous plaques on the cheeks, dorsal arms, and legs. The presence of vesicles suggests allergic contact dermatitis, and a history of application of a potential allergen supports this diagnosis.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare disease that is a manifestation of zinc deficiency. This is characterized by diarrhea, alopecia, and well-demarcated red, crusted plaques of the anogenital skin and perioral area.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis and granuloma gluteale infantum occur in the diaper area as well (see section “Granuloma Gluteale Infantum”).

Pathophysiology

Diaper dermatitis is multifactorial but primarily irritant contact, sometimes with candidiasis (Table 14-1). The irritants include wetness and friction of a diaper over skin exposed to urine and stool. Occasionally, atopic dermatitis plays a role (Fig. 14-13).

Irritant contact diaper dermatitis occurs when there is prolonged contact of the skin in the diaper area with irritating substances such as urine and feces. Infrequent diaper changes combined with heat and maceration of the skin under the diaper contribute to the severity of this dermatitis. It is often precipitated by the loose, frequent stools that accompany viral illnesses in infancy. Concentrated urine, proteolytic enzymes, and the high pH of stool that occurs with malabsorption are particularly problematic for sensitive skin. In addition, heightened efforts to cleanse the diaper area using harsh soaps and detergents expose already inflamed skin to further irritation and can set up a vicious cycle that is difficult to break.

TABLE 14.1 Diaper dermatitis: a multifactorial eruption | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Intertrigo, irritant dermatitis from chronic moisture and friction between skin folds, occurs more commonly in hot weather and is often accompanied by miliaria, or prickly heat. It is localized to the skin folds, where sweat and moisture are trapped, causing maceration and oozing.

Management

Treatment of diaper dermatitis is primarily aimed at changing the environment to eliminate common causes and re-evaluating the dermatitis that remains. Regardless of cause, all diaper dermatitis improves with elimination of irritating substances and a decrease in friction and maceration. This can best be accomplished with frequent diaper changes, the use of gel-containing disposable diapers that diminish direct contact of body substances with the skin, and the application of barrier cream to the involved areas. Pastes containing high concentrations of impervious zinc oxide or petroleum jelly are most effective (9). Copious quantities must be applied to the skin with each diaper change, and avoidance of further irritation from cleansing soaps and older, irritating wipes is critical (Fig. 14-14A, B). Newer emollient wipes may be better tolerated than water and a soft cloth (10). However, adherent stool is best removed by gently rinsing the perianal area with warm water and patting the skin dry. The application of a

barrier cream to anogenital skin is more effective than the aggressive removal of feces by rubbing or the use of harsh cleansers. Mild corticosteroid preparations such as 1% or 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment (not cream) hastens resolution of inflammation when applied twice daily and covered with barrier cream or ointment. Potent corticosteroids should not be applied under diaper occlusion, which enhances the effect of the medication. Adrenal suppression and deaths due to immunosuppresion have been reported in several infants treated with ultrapotent corticosteroids under diaper occlusion (11,12). Anticandidal agents should be added if there is a question of yeast. Nystatin is available in an ointment base and is less irritating than the azole creams. When disease is severe and erosions are present, antifungal medication should be administered orally until healing begins.

barrier cream to anogenital skin is more effective than the aggressive removal of feces by rubbing or the use of harsh cleansers. Mild corticosteroid preparations such as 1% or 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment (not cream) hastens resolution of inflammation when applied twice daily and covered with barrier cream or ointment. Potent corticosteroids should not be applied under diaper occlusion, which enhances the effect of the medication. Adrenal suppression and deaths due to immunosuppresion have been reported in several infants treated with ultrapotent corticosteroids under diaper occlusion (11,12). Anticandidal agents should be added if there is a question of yeast. Nystatin is available in an ointment base and is less irritating than the azole creams. When disease is severe and erosions are present, antifungal medication should be administered orally until healing begins.

Persistence of dermatitis when these measures are taken usually indicates an ongoing irritant process or an alternative diagnosis. Chronic diarrhea is a common cause for persistence of dermatitis, and this predisposes to yeast. An evaluation of the child’s diet and growth parameters and a search for underlying disease such as infection or malabsorption are indicated. In the absence of diarrhea, a skin biopsy may be helpful to identify other primary cutaneous disease.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common form of dermatitis in infants and adolescents.

Clinical Presentation

Seborrheic dermatitis first occurs at about 4 to 6 weeks of life, but rarely after a year of age. Scalp seborrhea is common after puberty, but genital involvement does not occur. In infants, the areas most commonly involved are the scalp, the face, the postauricular area, and the intertriginous folds including the neck, axillae, inguinal area, and between fat rolls. The scalp is usually involved first, with greasy, yellow scales with minimal inflammation. The diaper area is the second most common area to develop a rash. Seborrheic diaper dermatitis consists of erythematous, sharply marginated scaling plaques with greasy, macerated scales (Figs. 14-15 and 4-22). Candida frequently superinfects the area. The inguinal creases are more severely affected, but in many cases the groin and perineum are confluently involved. Spread to other flexural areas and even onto the trunk as isolated scaly plaques can occur (Fig. 14-15). Unlike atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis is nonpruritic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree