Disorder |

Inheritance |

Basic Defect |

Major Dermatologic Findings |

Associated Features |

Miscellaneous |

Ichthyosis vulgaris |

AD |

Unknown |

Mild-to-moderate white scales

Spares flexures and neck; involves face Keratosis pilaris Atopic dermatitis (50%) |

None |

Improves with age and warm weather |

X-linked ichthyosis (sterol sulfatase deficiency) |

XLR |

Mutation/deletion of steroid sulfatase gene |

Moderate-to-severe white-brown scale Spares face; involves neck |

Corneal opacities Possible increased risk of testicular malignancy |

Pregnancies with affected males have low to absent estriol levels; failure of spontaneous initiation of labor is common |

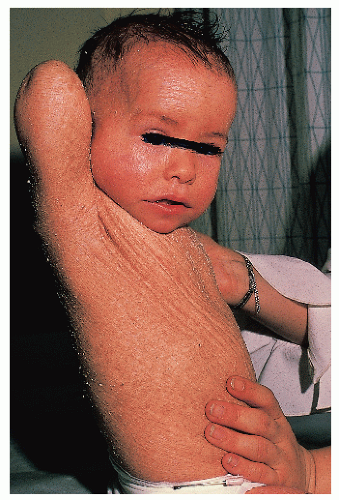

Bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (epidermolytic hyperkeratosis) |

AD |

Mutations in K1 or K10 (suprabasal keratins) |

Red skin with blisters and scale evident at birth

Marked hyperkeratosis

Face usually least affected

Inter- and intrafamilial variability |

Secondary skin infection, bacterial and fungal common |

Skin is tender; skin fragility improves with age |

Lamellar ichthyosis/nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma/congenital autosomal recessive ichthyosis |

AR |

Heterogenous. Some caused by mutations in transglutaminase 1 (TGM1), 12-R lipoxygenase (ALOX12B), lipoxygenase-3 (ALOXE3), ATP-binding cassette transporter 2 (ABCA2) |

LI: mild erythroderma; brown, adherent plate-like scale

NCIE: Erythroderma; fine, white scale

Many cases with overlap in phenotype |

Secondary tinea infection common |

Collodion membrane common at birth

Ectropion/ecla-bium common |

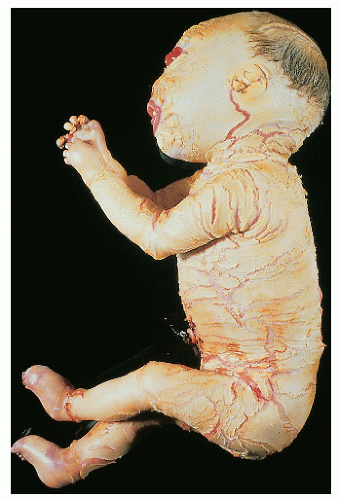

Harlequin fetus |

AR |

Unknown; probably heterogenous |

Severe, armor platelike hyperkeratosis In survivors, phenotype becomes similar to BCIE |

Among survivors, mental retardation has been noted in a few |

Rare spontaneous survival; handful of survivors treated with oral retinoids |

Conradi

Hunermann |

XLD

AR |

XLD: mutation in gene encoding delta(8)-delta(7) sterol isomerase emopamilbinding protein

AR: mutations in PEX7 gene |

Feathery scale on erythrodermic base

Follicular atrophoderma |

Seizures; MR

Chondrodysplasia punctata

Cataracts |

Asymmetry typical in XLD form |

Sjögren-Larsson syndrome |

AR |

Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency |

Mild-to-moderate fine, adherent scale

Pruritus |

Progressive spastic paraparesis

Mild retardation

Glistening white dots on retina |

Netherton syndrome |

AR |

Mutations in SPINK5 gene |

Variable erythroderma and scale

Classic pattern of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa |

Trichorrhexis invaginata (bamboo hair) |

Failure to thrive

Food allergies |

Collodion baby |

AR if isolated Otherwise, depends on underlying disorder |

Heterogenous |

Plastic wrap-like membrane peels within few weeks after birth, revealing underlying skin, which may range from minimally xerotic to lamellar ichthyosis |

This is a feature of many disorders including lamellar ichthyosis, hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, Gaucher disease and lamellar exfoliation of the newborn |

|

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; BCIE, bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma; XLR, X-linked recessive; K, keratin; MR, mental retardation. |