Genital Pruritus and the Eczematous Diseases

Peter J. Lynch

The sensation of pruritus (itching) is carried from mucocutaneous tissue to the sensory cortex by unmyelinated type C sensory nerve fibers. These same fibers also carry certain types of pain. It is not known precisely why triggering of these twig-like nerve endings, which are located in the epidermis and upper dermis, sometimes results in the perception of itching and at other times the perception of pain. However these sensations are qualitatively different. That is, a quantitative increase in stimulation does not convert itching to pain. Moreover, since the impulses transmitted by these nerves are interpreted in the brain within the sensory cortex, it is apparent that both itch and pain can have a peripheral component, a central component or a mix of these two components.

Genital pruritus occurs in two settings. It may arise from apparently normal appearing tissue (“primary” pruritus) or it may occur as a part of separate disease process on visibly abnormal tissue (“secondary” pruritus). Conceptually it is worth trying to separate the two forms of pruritus, but since scratching occurs in both settings, the clinical appearance at the time of examination often does not allow one to separate the two processes. When that is the case, treatment specifically directed toward the cessation of scratching and/or rubbing will usually allow for separate identification. That is, when the scratching completely stops, the skin will return to its normal appearance if the process is primary or will reveal an underlying disorder if the process is secondary. In both instances, adverse environmental factors in the anogenital area, such as heat, sweating, friction, and irritation from urine, feces, and vaginal secretions, will often initiate or aggravate the degree of pruritus.

When skin is scratched or rubbed on a continual basis over a period of days or weeks, the tissue takes on an appearance classical for the eczematous (dermatitic) diseases. For this reason, “eczema” and “dermatitis” (which are synonyms) can be defined morphologically. The morphologic pattern for the eczematous diseases is represented by the presence of red papules and plaques with poorly marginated borders, overlying scale, and evidence of epithelial disruption and/or lichenification. Epithelial disruption is most often recognized by the presence of excoriations, but other signs of epithelial disruption can include weeping, crusting, fissuring, or the presence of yellow-colored scale. This yellow color is due to the presence of small amounts of plasma that coats and covers the otherwise gray, white, or silver color of scale. When rubbing is more prominent than scratching, the calluslike response of lichenification may supplant much of the evidence for epithelial disruption. Lichenification is recognized clinically by three features: palpably thickened skin, exaggerated skin markings, and lichen-type scale. Note that lichen-type scale, because of its adherence to the epithelium, is more or less colorless when dry but becomes quite white when it absorbs moisture as is likely to happen in the genital area.

Lesions possessing an eczematous clinical appearance as described in the paragraph above have a characteristic histological appearance on biopsy. This microscopic appearance demonstrates spongiotic inflammation (inflammatory cells accompanied by intercellular and intracellular edema within the epithelium) when the process is acute and by acanthosis (epithelial thickening often termed “psoriasiform dermatitis”) when the process is chronic. This is the histological appearance of all of the disorders discussed in this chapter. Since all of these diseases share a common histologic appearance, pathologists are usually unable to separately identify each of the disorders that exist within the general category of eczematous disease. For this reason, when a pathologist makes a diagnosis of “spongiotic dermatitis” or “psoriasiform dermatitis” it is necessary for the clinician to make a clinical-pathologic correlation in order to arrive at a more specific diagnosis (1).

IDIOPATHIC (“ESSENTIAL”) PRURITUS

When itching occurs but leads to only a little rubbing or scratching, the involved tissue may look quite normal on clinical examination. This process, when it develops in the anogenital area, is sometimes termed “pruritus ani,” “pruritus vulvae,” or “pruritus scroti.” However when biopsies are obtained from this normal appearing tissue, there is almost always some evidence of spongiotic dermatitis and/or psoriasiform dermatitis. This microscopic finding, together with the regularly present evidence of the “itch-scratch” cycle, leads me to believe that this represents a subclinical variant of atopic dermatitis (see below).

ATOPIC DERMATITIS AND LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS

The nomenclature regarding atopic dermatitis and its variants is somewhat complex and controversial. The term “atopy” has been defined in many ways, but most often the definition includes a genetic predisposition for the development of hypersensitivity allergic IgE reactions to common environmental antigens. Thus, atopic individuals frequently develop allergic rhinitis (hay fever), asthma, or atopic dermatitis. A semantic problem arises when an eczematous eruption occurs in an individual who lacks a personal or prominent family history of hay fever or asthma. In this setting the eczematous process has alternatively been called neurodermatitis, infantile eczema, childhood eczema, and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). Given the lack of consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (2) and in view of the fact that all of these eczematous eruptions share the presence of the “itch-scratch cycle,” I believe it is appropriate to use the term atopic dermatitis (for the generalized form) and LSC (for the localized form) of the disease regardless of whether or not the individual has other clinical evidence of atopy. Moreover, since genital involvement very often occurs in the absence of eczematous disease elsewhere, it will be referred to as LSC for the purposes of this chapter.

Clinical Presentation

Atopic dermatitis is an extremely common disorder affecting about 15% of the population in Western countries. The localized form of atopic dermatitis, genital LSC, occurs in both sexes and at all ages. It is commonly encountered in those who are adults and in this group it is found in women a little more frequently than in men. In children, boys are affected somewhat more often than girls. The prevalence and incidence of genital LSC are unknown but based on a few older studies and discussion at conferences, it is probably the single most common symptomatic condition involving the anogenital area.

History

Possibly because of embarrassment, patients with genital LSC rarely seek medical attention until the problem has been present for weeks or months. Often the itching arises subtly, but in women a specific event, most often vaginal discharge (perceived to be a yeast infection), will be identified by the patient as the initial trigger. In either setting, once itching has occurred, scratching almost inevitably follows. Most patients describe the itching as severe and find that nothing in terms of home remedies or over-the-counter medications will relieve it. In the most intractable cases, patients will scratch until pain caused by excoriation replaces the pruritus. In instances of long-standing duration, patients will often shift from scratching to rubbing since they find they can alleviate some of the itching without causing the pain and tissue damage that arises with excoriation.

In time, a vicious circle of itching followed by scratching, followed by more itching and more scratching, develops. This is termed the “itch-scratch cycle” and its presence is the pathognomonic and defining characteristic of atopic dermatitis and LSC. Sometimes the patients are conscious of the scratching and many such individuals continue on with the scratching “because I can’t make myself stop” or “because it feels so good to scratch.” Others are unaware of scratching and tend to think that they scratch very little. This is quite analogous to the personal unawareness that develops with fingernail biting, knuckle cracking, and other such “habit tics.”

Scratching during the daytime primarily occurs after using the toilet, when changing clothes after work, and in the evening when one gets undressed for bed. Scratching almost always also occurs episodically at night during the lighter stages of non-REM sleep and it is associated with an abnormal increase in the number of partial awakenings (3,4). I have termed this nocturnal scratching the “Penelope phenomenon” based on Homer’s tale of Odysseus (Ulysses) and his wife Penelope (5). When Odysseus tarried for many years on his voyage home from the Trojan War, Penelope was urged to declare him deceased and marry one of her many suitors. She agreed to do so once she had completed weaving a funeral shroud for her dying father-in-law. During the day she wove the shroud, but at night when everyone was sleeping she would undo most of the previous day’s weaving. The Penelope phenomenon thus represents the nighttime scratching that undoes the benefits of a good daytime therapeutic program.

Examination

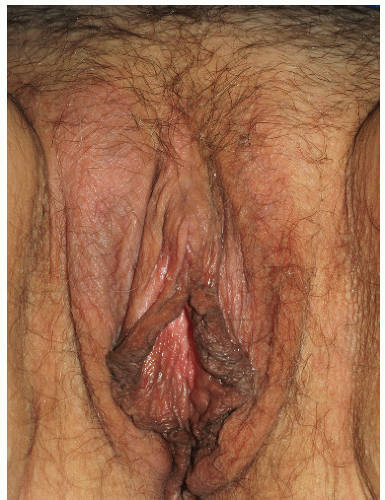

As indicated above, LSC shares the morphological characteristics of all eczematous diseases. This includes erythematous, poorly marginated, scaling papules and plaques with evidence of epithelial disruption and/or lichenification (Figs. 4-1, 4-2, 4-3, 4-4, 4-5 and 4-6). But in contrast to other eczematous diseases, the severity of excoriation and/or lichenification often allows for correct clinical identification. This may not be true in mild cases because the warm, moist environment of the anogenital area may obscure some of the characteristic morphological features. First, scale may not be as visibly apparent (though it can still be recognized by roughness on palpation) as it is with LSC in other locations (Figs. 4-7 and 4-8). Second, scale is hydrophilic and when it takes up water it turns white. This white color can be fairly prominent when a patient first undresses but decreases as evaporation reduces the moisture content (Fig. 4-9). Third, deep scratching may destroy or remove melanocytes, leaving hypopigmented areas when the scratch marks heal (Fig. 4-10). Fourth, the anogenital area pigments easily. When LSC has been

present for a long time, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation often develops. This can decrease the apparentness of erythema, leading one to underestimate the amount of inflammation that is present (Figs. 4-11 and 4-12). This is especially likely in patients with naturally dark skin.

present for a long time, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation often develops. This can decrease the apparentness of erythema, leading one to underestimate the amount of inflammation that is present (Figs. 4-11 and 4-12). This is especially likely in patients with naturally dark skin.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LSC is usually made on the basis of the clinical findings. In some instances it is not clear whether the LSC is arising de novo or is superimposed on another underlying dermatological problem. This is particularly likely to happen with genital psoriasis but is also common with tinea cruris in men and lichen sclerosus in women. One might think that biopsy could identify the underlying problem in the setting of secondary LSC, but this is often not true. In the acute phase of LSC, spongiotic inflammation will be prominent and this finding may obscure the presence of an associated disorder.

FIG. 4-2. Obvious erythema, edema, excoriations, and scale of this vulva are produced by chronic rubbing and scratching. |

FIG. 4-5. This patient has not only poorly demarcated, thickened skin as a result of rubbing, but also excoriations produced by scratching. |

Even more confusion generally occurs when chronic LSC is biopsied. In this situation, the report is often signed out as “psoriasiform dermatitis,” which will not offer the clinician much help in trying to determine whether or not psoriasis is present. If this occurs, the clinician will have to undertake a clinical-pathologic correlation (1). Because candidiasis is the condition most commonly associated with the development of LSC in women, culture and/or KOH examination for associated candidiasis will be worthwhile. In both sexes, if the upper inner thighs are involved it may be useful to obtain a KOH and/or culture for dermatophyte fungi associated with tinea cruris.

FIG. 4-7. Scale is subtle on this vulva due to the moist environment, although thickening from rubbing is remarkable; LSC can sometimes be remarkably unilateral. |

Psoriasis can be very similar in appearance to LSC, especially in the anogenital area where LSC may be

superimposed over psoriasis. Helpful clues to the presence of psoriasis would be the presence of more typical psoriatic plaques in characteristic sites elsewhere, the identification of typical psoriatic nail changes, and the presence of psoriatic arthritis. Unfortunately, as noted above, biopsy may not be helpful in separating psoriasis from LSC.

superimposed over psoriasis. Helpful clues to the presence of psoriasis would be the presence of more typical psoriatic plaques in characteristic sites elsewhere, the identification of typical psoriatic nail changes, and the presence of psoriatic arthritis. Unfortunately, as noted above, biopsy may not be helpful in separating psoriasis from LSC.

FIG. 4-9. The right medial labium majus exhibits excoriations from scratching and thickened epithelium from rubbing; this thick skin appears white due to hydration of this thick epithelium |

FIG. 4-10. Scratching has destroyed and removed melanocytes, so that the skin has areas of hypopigmentation and depigmentation. |

FIG. 4-11. In the presence of lichenification, inflammation in dark complexioned people appears hyperpigmented rather than red. Once again, lichenoid scale appears shiny rather than flaking. |

In women, LSC frequently overlies vulvar lichen sclerosus and may obscure the typical clinical characteristics of this condition. However, architectural damage such as the presence of clitoral hooding, loss of the labia minora, or the presence of purpura would help to identify associated lichen sclerosus. Biopsy is helpful in this situation.

FIG. 4-12. Even patients who are not naturally dark sometimes exhibit hyperpigmentation that obscures the inflammation of lichen simplex chronicus, as seen on this left labium majus. |

At the histological level, LSC can be confused with the often rather mundane appearance of the differentiated (non-HPV related) squamous cell intraepithelial neoplasia (6,7). Moreover the frequent histological presence of epithelial acanthosis, similar to that seen in LSC, immediately adjacent to the carcinoma raises a question of what, if any, relationship might exist between LSC and the development of genital squamous cell carcinoma.

Pathophysiology

The cause of LSC is not known. A large proportion of the patients who develop LSC have a personal or immediate family history of hay fever, asthma, or earlier eczematous skin disease and thus are presumably atopic. But, it is still not clear just how atopy results in the development of LSC. There is increasing appreciation that many, if not most, patients with atopic dermatitis possess genetic defects (notably mutations in the fillagrin gene) that interfere with the normal development of the outer layer of the epidermis (“the barrier layer”). These barrier layer defects allow easier exposure and processing of both irritants and allergens. Presumably these defects in the barrier layer also allow easier triggering of the terminal branches of sensory nerves that carry itch and light pain. Even though peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels are frequently present, atopic dermatitis is different from other atopic disorders in that the immune dysfunction associated with it is T-cell mediated rather than occurring as a type 1 IgE-related humoral dysfunction as occurs in hay fever and asthma. Atopic dermatitis appears to involve the TH2 component of the cell-mediated immune system and this process is presumably responsible for the increased serum IgE levels and peripheral eosinophilia.

In addition to such peripheral abnormalities, it seems likely that there are also important central aspects. Possibly there is a heightened appreciation for itching at the level of the sensory cortex and maybe an innate tendency for the development of an obsessive-compulsive-like scratching that characterizes the itch-scratch cycle in LSC. Some clinicians also believe that patients with atopic dermatitis, and by extrapolation, some of those with LSC, have mild-to-moderate psychological abnormalities such as heightened anxiety levels and stress vulnerability that may lead to worsening of the disease (8,9). Moreover some clinicians, including myself, believe that there is a predilection for internalization of anger and hostility that is distinctive for patients with atopic dermatitis.

At the clinical level it is apparent that factors in the local environment, such as heat and sweating, trigger both the initiation and the continuation of the process. As opposed to this important role for contact irritants, the role of contact allergens is much more controversial. A significant proportion of patients with anogenital dermatitis are reported to have positive patch tests (10,11) that were considered to be clinically relevant. However data indicating that removal of the offending agent leads to resolution of the problem are lacking. Based on our personal experience, patch testing in patients with LSC is rarely necessary or justifiable.

Management

LSC is a chronic disease. Left untreated, the itch-scratch cycle persists indefinitely, although it can be somewhat episodic rather than consistently present. This process is extremely discomforting for the patient and it may lead to a significant decrement in quality of life (12). Other troublesome sequelae may include hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation due to activation or destruction of melanocytes, respectively. At the hypothetical level it has been suggested that chronic scratching might lead to hyperproliferation-type cell signaling for epithelial cells and that in turn might act as “promoter” for the development of squamous cell carcinoma if previous “initiating” events such as genetic mutations should have occurred (6,7,13).

Treatment for LSC can be extremely effective. Approach to therapy includes five basic steps: (1) improvement in the local environment to reduce the triggering that leads to itching and scratching, (2) restoration of normal barrier layer function, (3) reduction in inflammation, (4) cessation of the itch-scratch cycle, (5) identification and treatment for any detrimental psychological factors that may be present.

Improvement in the Local Environment

As mentioned previously, heat and sweat act as provoking factors for the development of both itching and inflammation. Removing or reducing these factors is certainly desirable but is more difficult to do than one might expect. Immediate steps include a change to less occlusive, tight fitting clothing and the use of materials (such as cotton and cotton-blends) that allow for better movement of air. Contrary to decades of physician recommendations, however, the avoidance of dyes in underwear (“use white underwear only!”) lacks any scientific merit. Other approaches include the avoidance of prolonged sitting, the use of cloth rather than vinyl for seating-surfaces, and the use of cooler temperatures in the workspace or home. Weight loss can help those who are particularly obese by way of decreasing intertriginous surface area and reducing frictional rubbing. Note that the use of hair dryers, even on their lowest temperature settings, in an attempt to dry the area is not helpful and in most instances is actually detrimental.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree