Erosive and Vesiculobullous Diseases

Libby Edwards

The various erosive and blistering disorders are often morphologically indistinguishable when occurring on genital skin. Blisters are skin lesions that are filled with fluid. However, when blisters occur on fragile skin such as the genital area, the blister is unroofed quickly. This loss of epithelium results in a shallow area of denuded skin called an erosion, as distinguished from an ulcer, which is a deeper lesion, extending into or even through the dermis. Erosions can occur not only from ruptured blisters, but also from trauma, from epithelial necrosis produced by intense inflammation, or from necrosis resulting from tumor. Erosions resulting from a blister are usually well demarcated and round, or when blisters coalesce before eroding, arcuate erosions can result. Those resulting from trauma such as an excoriation are usually linear or angular. Erosive skin diseases can be infectious, immunemediated, or malignant or can arise from excoriations from scratching, as in vulvar dermatoses. Ulcers are discussed in Chapter 10. There is overlap between erosive and ulcerative diseases, and many conditions may cause both together or sequentially.

NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DERMATOSES THAT SOMETIMES ERODE

Erosive Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a skin disease that exhibits variable morphologies on genital skin. Erosive lichen planus is the most common noninfectious erosive condition occurring on the vulva, although it is less common on the penis and almost nonexistent in circumcised men. Red papules (Chapter 3) are more common than erosions in men, and wet skin often exhibits white skin lesions (Chapter 11). Many patients exhibit more than one form of lichen planus.

Clinical Presentation

Erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus affects adults only, and women are far more often affected by the erosive form, particularly in the United States where circumcision is regularly performed on most newborn boys. Fewer than 25% of women with genital lichen planus have concurrent cutaneous involvement. Patients often report pruritus, but no pleasure with scratching, although the predominant complaint is that of burning, irritation, rawness, dysuria, dyspareunia, and postcoital bleeding. Many patients with erosive genital lichen planus also report mouth pain, especially with hard food such as chips, spicy foods, and acidic foods.

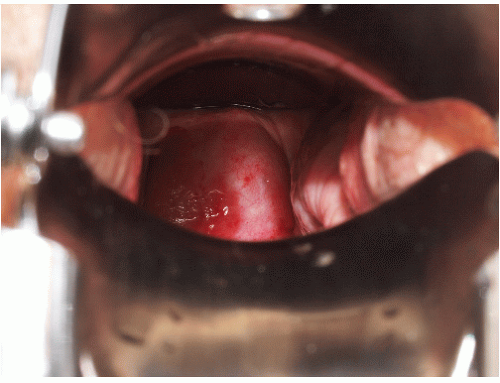

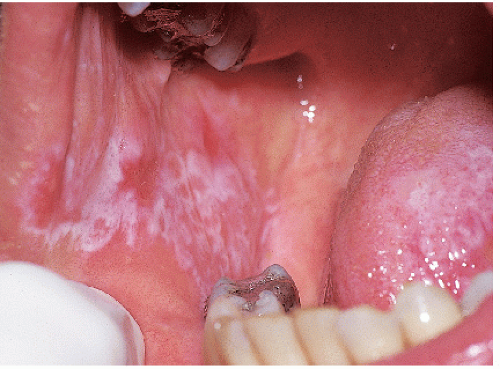

Although lichen planus manifests with many different morphologic appearances, classic lesions on keratinized skin are pruritic, violaceous, flat-topped papules (see Chapter 3). However, on mucous membranes, the most common morphologies are white lacy papules and plaques (see Chapter 11) or erosions. The white and eroded lesions can present separately or together. In 1982, Pelisse and associates described the vulvovaginalgingival syndrome, introducing erosive lichen planus as a separate subgroup in women. Characteristically, these patients suffer erosions of the vulva, vagina, and oral mucosa at some stage of the disease, although not necessarily initially. Involvement of the modified mucous membranes of the vulva is usual, with bright red, thin epithelium and erosions most marked in the vestibule. These can be nonspecific, but often surrounding white epithelium and reticulate white lacy plaques reveal the diagnosis of lichen planus (Figs. 9-1, 9-2, 9-3, 9-4 and 9-5). With chronic erosive lichen planus, scarring occurs (Fig. 9-6). Labial resorption and scarring of the clitoral hood over the clitoris are common. Narrowing of the introitus is also a frequent complication.

Vaginal erosions are usual with erosive vulvar lichen planus (Fig. 9-7). Even when vulvar lichen planus is papular rather than erosive, accompanying inflammatory vaginitis produced by lichen planus is common (see Chapter 15). Erosive vaginal lichen planus is tender and chronic and produces purulent vaginal secretions that incite an irritant contact dermatitis in the vestibule. Vaginal adhesions occur with severe disease, sometimes producing obliteration of the vaginal space that make sexual intercourse or the introduction of a speculum impossible.

Gingival lesions may be localized or generalized, primarily manifested by tender erosions and desquamative gingivitis, sometimes with surrounding solid or reticulate white papules (Fig. 9-8). Often, linear reticulate papules or erosions occur on the buccal mucosa (Fig. 9-9). Esophageal lichen planus is increasingly recognized and is more common than the literature suggests. Strictures

producing dysphagia and weight loss are suggestive of this involvement, and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is a serious complication (1).

producing dysphagia and weight loss are suggestive of this involvement, and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is a serious complication (1).

FIG. 9-2. Lichen planus is by far the most common cause of nonspecific chronic erosions, especially those that involve the vestibule. |

Penile lichen planus is more commonly associated with lichen planus at other cutaneous sites than is vulvovaginal

lichen planus. Lesions are less often eroded, but when erosions occur, they are very painful (Figs. 9-10 and 9-11). These erosions may be associated with oral lesions and run a similar prolonged clinical course to that seen in women (2). Men with erosive penile lichen planus also experience scarring, with phimosis if uncircumcised, or obliteration of the sharp distinction of the glans from the

shaft in the circumcised penis. Perianal lesions sometimes occur in both genders (Fig. 9-12).

lichen planus. Lesions are less often eroded, but when erosions occur, they are very painful (Figs. 9-10 and 9-11). These erosions may be associated with oral lesions and run a similar prolonged clinical course to that seen in women (2). Men with erosive penile lichen planus also experience scarring, with phimosis if uncircumcised, or obliteration of the sharp distinction of the glans from the

shaft in the circumcised penis. Perianal lesions sometimes occur in both genders (Fig. 9-12).

FIG. 9-3. This erosion is pathognomonic for lichen planus because of the surrounding white, interlacing papules. |

FIG. 9-5. Severe lichen planus is extremely painful and requires systemic as well as topical therapy. |

FIG. 9-6. Even relatively inactive lichen planus can eventuate in remarkable scarring, as has occurred in the patient with a 2 mm vaginal opening and urinary obstruction. |

FIG. 9-8. Posterior buccal mucosal lesions regularly accompany genital lichen planus and occur often in any patient with any form of lichen planus on any skin surface. |

FIG. 9-10. The uncircumcised penis with erosive lichen planus, like the vulva, exhibits nonspecific erosions. |

FIG. 9-11. Erosive lichen planus on an uncircumcised glans may appear crusted because of the dry environment. |

There are rare reports of squamous cell carcinoma occurring in both vulvar and penile lichen planus. Indurated erosions and ulcers should be biopsied, as should chronic hyperkeratotic areas.

There have been reports of lichen planus occurring more often in patients with hepatitis C, and reports discounting this association. A recent meta-analysis reports that this association is real, at least in some geographic locations (3).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of lichen planus can be made with confidence when erosions are accompanied by white, lacy, reticulate, or fernlike papules of the genitalia or mouth. Otherwise, a biopsy is required, although most often the histology is returned as “lichenoid dermatitis” consistent with but not diagnostic of lichen planus. The biopsy should be taken from the edge rather than the center of an erosion, and it should be submitted for routine histology. If the biopsy is very nonspecific or is suggestive of an autoimmune blistering disease such as cicatricial pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris, an additional biopsy submitted for direct immunofluorescence will be necessary. This biopsy should be obtained from normal, perilesional skin and stored in transport media rather than formalin.

Histologic features of erosive lichen planus include a dense, lymphocytic, dermal bandlike infiltrate extending to and damaging the basal layer. A prominent granular cell layer, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis are common, but erosive mucous membrane lichen planus often exhibits epithelial thinning and flattening. A biopsy of eroded skin that does not include epithelium cannot demonstrate a diagnosis of lichen planus, so biopsy sampling should include the epithelialized edge of an erosion. Colloid and Civatte bodies are frequently seen in the lower epidermis and upper dermis, and a direct immunofluorescent biopsy makes these more easily visualized.

Most chronic erosive skin diseases are in the differential diagnosis of erosive genital lichen planus. Pemphigus vulgaris and cicatricial pemphigoid are nearly indistinguishable, but less common and usually more easily diagnosed by routine and direct immunofluorescent biopsy. Often, surrounding white epithelium suggests the diagnosis of erosive lichen planus, but any chronic erosion can induce surrounding nonspecific white epithelium. Sometimes, this white epithelium can resemble lichen sclerosus, but lichen sclerosus never affects the vagina, and it shows a characteristic crinkled or occasionally waxy texture unlike that of lichen planus. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, severe erosive candidiasis, and an irritant contact dermatitis to an agent such as podophyllum resin can mimic erosive lichen planus, but these are acute rather than chronic in onset. Like erosive lichen planus, plasma cell mucositis also exhibits red, moist, glistening papules, and plaques that may appear erosive. The histology differentiates lichen planus from plasma cell vulvitis or balanitis and from the erosive genital lesions of graft versus host disease that may also be associated with lichenoid skin lesions.

Pathophysiology

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition of unknown etiology. However, evidence suggests this disorder may be an autoimmune disease of cellular immunity. Injury of the basement membrane by cytotoxic T cells is

central, and recent investigations report amplification of this injury by interferon alpha derived from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (4). Other autoimmune diseases cluster with lichen planus, including lichen sclerosus (5).

central, and recent investigations report amplification of this injury by interferon alpha derived from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (4). Other autoimmune diseases cluster with lichen planus, including lichen sclerosus (5).

Management

The management of erosive lichen planus often is difficult. Mild disease is often adequately controlled by supportive measures and topical corticosteroids, whereas more severe disease requires the systemic use of systemic antimetabolites and immunosuppressive agents with variable success. Circumcision is sometimes curative in men (6).

Topical emollients such as petrolatum are soothing, as are measures such as air-drying rather than towel-drying. Because vulvovaginal lichen planus occurs primarily in the postmenopausal age group, topical or systemic estrogen replacement can be crucial, avoiding an additional and easily corrected cause for mucosal thinning.

First-line specific therapy for lichen planus is corticosteroid therapy. Potent topical steroid ointments (e.g., clobetasol propionate 0.05%) applied to vulvar or penile lesions twice daily can be beneficial. Creams, gels, lotions, and solutions are to be avoided because of the irritation induced by the alcohols regularly contained in these vehicles. This medication can also be inserted intravaginally at night, as can 25 mg hydrocortisone acetate rectal suppositories or hydrocortisone foam.

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 40 to 60 mg/day) effect significant and rapid improvement in most patients, but the condition recurs when the medication is stopped. The benefit is delayed in onset for all other treatments, and other therapies improve lichen planus less regularly. Methotrexate 25 mg weekly sometimes is beneficial for lichen planus (7). There are reports that oral retinoids such as isotretinoin 40 to 80 mg/day and acitretin at about 25 mg/day have been helpful, but side effects including teratogenicity and altered liver function require careful monitoring, and more evidence is needed from larger clinical trials as to their effectiveness. In addition, the long half-life of some retinoids is problematic. Other systemic treatments tried include oral griseofulvin at 500 mg twice daily, dapsone 100 to 150 mg daily, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenylate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, with anecdotal benefit in some patients; clinician familiarity with these medications for appropriate monitoring is important. Topical cyclosporine (using the oral liquid or solution intended for intravenous administration) four times a day has been useful for occasional patients, but the expense, local irritation, and minimal benefit render it impractical for most (8). Thalidomide at 100 to 150 mg/day is a theoretical potential therapy (9), as are topical tacrolimus (10) and pimecrolimus (11). More recently, topical rapamycin has been suggested as beneficial for refractory oral erosive lichen planus (12). Extracorporeal photochemotherapy has been reported beneficial in a series of patients with refractory oral erosive lichen planus, an expensive therapy not available to most clinicians (13). No one therapy is ideal, and few produce consistent improvement without significant risks or side effects.

Lastly, surgery is occasionally needed to separate vaginal adhesions, reverse tightening of the introitus, or to uncover a buried clitoris. Skin disease should be controlled as well as possible before surgery is contemplated, and great care has to be taken postoperatively to prevent rapid scar reformation. Use of topical steroids and dilators is advisable.

Erosive anogenital lichen planus is chronic and painful, and there are no standard treatment measures that help all patients. Nor are there any controlled trials that evaluate therapy for anogenital lichen planus. However, experience suggests that there are various therapies that help some patients. Occasionally, erosive anogenital lichen planus remits, but this is the exception. Also, because of the risk of squamous cell carcinoma, patients should be checked regularly throughout the course of the disease.

Plasma Cell Balanitis and Vulvitis

The origin of Zoon balanitis or vulvitis (also called balanitis or vulvitis circumscripta plasmacellularis, inflammatory erythroplasia) is unknown, although some physicians believe that plasma cell vulvitis and balanitis are related to lichen planus (see also Chapter 3).

Clinical Features

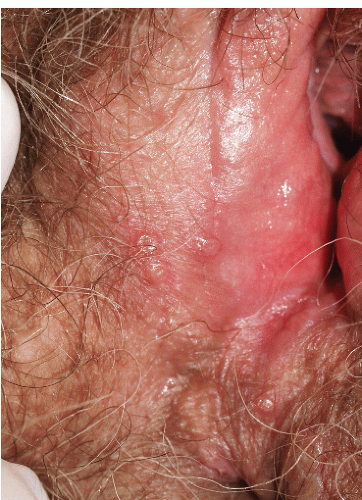

Plasma cell vulvitis and balanitis present as a glistening, red, usually solitary plaque on the glans penis or vulva (Figs. 9-13 and 9-14). This may be asymptomatic or may present with mild pruritus. Erosive and vegetative types may occur, which are more painful. Lesions may

persist for years, but they usually resolve slowly leaving a “rusty stain” resulting from microhemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition. The condition may recur.

persist for years, but they usually resolve slowly leaving a “rusty stain” resulting from microhemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition. The condition may recur.

FIG. 9-13. This brown-red plaque around the urethral meatus is characteristic of plasma cell (Zoon) mucositis; this glistening plaque can be difficult to differentiate from an erosion at times. |

Diagnosis

Plasma cell vulvitis and balanitis are diagnosed by the morphology of characteristic skin lesions, and it is confirmed on biopsy. Histology shows a thinned epidermis, sometimes with upper layers absent or detached from the dermis. Flattened keratinocytes separated by intercellular edema are distinctive. Red blood cells may be seen in the upper dermis and epidermis, and hemosiderin and vascular proliferation are common in the dermis. A dermal bandlike dense infiltrate with a predominance of plasma cells is characteristic.

Other diseases that can be confused with plasma cell vulvitis and balanitis include erosive lichen planus, intraepithelial neoplasia (also called Bowen disease, erythroplasia of Queyrat), and sometimes, Paget disease. Erosive candidiasis also can resemble Zoon vulvitis or balanitis.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of plasma cell mucositis is unknown. Some believe that this may be related to lichen planus, and others suspect it is a nonspecific reaction pattern to an inflammatory process.

Treatment

In men, circumcision is curative. Otherwise, potent topical corticosteroids offer some symptomatic relief and improvement in appearance in many patients, but relapse is the rule on discontinuation of treatment. Topical tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and masoprocol have been useful in some, but reported results of therapy are conflicting (14,15 and 16). Intralesional corticosteroids, imiquimod, and CO2 laser have been reported beneficial at times (17,18 and 19).

There is one report of squamous cell carcinoma in situ (intraepithelial neoplasia) in a patient with plasma cell balanitis, so that ongoing surveillance is recommended (20).

Erosive Lichen Sclerosus (Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus, Hypoplastic Dystrophy)

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic fragile dermatosis characterized by atrophic white plaques, occurring most commonly on the genital skin of both sexes, although there is a female preponderance of 10:1 (see Chapter 11 for primary discussion).

The usual presenting symptom of lichen sclerosus is severe pruritus, often leading to painful erosions as this fragile skin is scratched (Fig. 9-15). These excoriations and other erosions resulting from fragility of the skin can be very painful and can predispose to secondary infection. The atrophic skin fissures more easily, so patients may present with pain on intercourse, and young girls often experience constipation resulting from pain of fissures with defecation (boys do not experience perianal lichen sclerosus). Lichen sclerosus is characterized by pallor and thin, crinkled skin; advanced disease is often associated with resorption of the labia minora, a clitoris covered by scar, and narrowing of the introitus. Purpura and hyperkeratosis are common, and lichen sclerosus may spread to perianal skin in women. Extragenital involvement occurs in about 6% of women of patients (unpublished data), and oral and vaginal mucosal involvement is rare.

Squamous cell carcinoma occurs in about 3% of patients with untreated vulvar lichen sclerosus, but erosive and hyperkeratotic lesions of lichen sclerosus in elderly patients are forms more likely to exhibit malignant change. In addition, lichen sclerosus is found in more than 50% of specimens from vulvectomies performed for squamous cell carcinoma.

Eroded lichen sclerosus is sometimes indistinguishable from erosive lichen planus, and these two diseases are known to coexist in some patients. Erosive and scarring lichen sclerosus can also mimic other chronic erosive or blistering diseases such as cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris, so biopsy and examination of other mucous membranes and skin surfaces may be necessary to make the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

For men, circumcision is usually curative. Otherwise, the main treatment is potent topical corticosteroid ointment such as clobetasol propionate 0.05%, applied twice daily until improvement occurs, and then the frequency is reduced. Eroded lichen sclerosus is more likely than noneroded disease to present with bacterial or candidal superinfection, which should be addressed. In addition, these patients are more likely to develop superinfection after the initiation of an ultrapotent corticosteroid. Early detection and treatment, or even prophylaxis during the first week or so of therapy until the skin improves, can be extremely helpful.

This is a chronic skin disease that requires chronic corticosteroid therapy for ongoing control. Patients should undergo ongoing surveillance to assess the activity of the disease, side effects of medication, and any early signs of malignant transformation.

Lichen Simplex Chronicus (Eczema, Atopic Dermatitis, Neurodermatitis)

This excruciatingly pruritic condition exhibits erosions only secondarily, as a result of excoriation (see also Chapter 4). A genetic tendency to itch in the presence of local irritation initiates an itch-scratch cycle characterized by skin changes produced by rubbing (lichenification, scale, and erythema) and scratching (linear erosions of excoriation) (Figs. 9-16 and 9-17). The diagnosis is generally recognized by the history of scratching and the observation of irregular or linear erosions consistent with excoriations on the vulva or scrotum. Therapy includes topical corticosteroids, infection control, and nighttime sedation to minimize scratching during sleep.

Reiter Syndrome

The skin findings of Reiter syndrome classically include balanitis or cervicitis, often with erosions and crusting (see also Chapter 8). It is genetically determined and often runs a prolonged and relapsing course. This disease appears to be an abnormal host response to infection. Much more common in males, this response can occur either to a preceding enteric (gram-negative) infection or to a genitourinary, sexually transmitted Chlamydia infection.

FIG. 9-16. The itching of lichen simplex chronicus results in rubbing that thickens the skin, producing the white color, and scratching that can produce erosions. |

One characteristic presentation consists of plaques of pustules that occur primarily on the glans penis, but these pustules erode quickly because of their fragile

nature on thin skin. Crusting follows on the dry glans, but the uncircumcised glans exhibits erosions. Plaques with pustules and crusting occur on the vulva; palms and soles are often prominently involved (Fig. 9-18). On the palms and soles, these crusted plaques develop superimposed hyperkeratosis (keratoderma blennorrhagica). Other clinical features include acute oligoarthritis, usually of the knee or ankle, and problems with associated tendons and ligaments, conjunctivitis, mouth ulcers, urethritis or cervicitis, balanitis, and occasionally, cardiac problems.

nature on thin skin. Crusting follows on the dry glans, but the uncircumcised glans exhibits erosions. Plaques with pustules and crusting occur on the vulva; palms and soles are often prominently involved (Fig. 9-18). On the palms and soles, these crusted plaques develop superimposed hyperkeratosis (keratoderma blennorrhagica). Other clinical features include acute oligoarthritis, usually of the knee or ankle, and problems with associated tendons and ligaments, conjunctivitis, mouth ulcers, urethritis or cervicitis, balanitis, and occasionally, cardiac problems.

FIG. 9-17. Erosions with lichen simplex chronicus are most often linear and angular from scratching with fingernails. |

FIG. 9-18. Inflammation and pustules of the glans penis of a patient with Reiter syndrome often develop into erosions. |

The skin findings of Reiter syndrome are usually diagnosed by the clinical appearance and recognition of the constellation of symptoms. Unfortunately, there is no specific test for Reiter syndrome, but histologic confirmation of characteristic cutaneous abnormalities, which are identical to those of pustular psoriasis, is often helpful. Diseases that should be excluded include pustular psoriasis, gonococcal infection, and Behçet syndrome. Reiter syndrome is seen in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients.

Treatment is difficult because there is no one safe agent that dampens the host response overall. Antibiotics are used to shorten the initial infection, and otherwise each organ is treated symptomatically. Topical steroids may be helpful for the balanitis, but systemic steroids are reserved for severe complications such as cardiac involvement. Methotrexate and systemic retinoids such as acitretin are extremely useful for the skin abnormalities.

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

This is a very rare condition that is caused by a glucagonoma, an α-cell tumor of the pancreas which is usually malignant. Serum levels of glucagon are elevated. Patients are usually ill with weight loss, diarrhea, malabsorption, and diabetes.

The rash begins as erythematous papules around orifices and flexures, including those of the genitalia. These papules coalesce into plaques, and central erosions occur and crust, eventually producing a circinate migratory erythema.

Histology of the skin shows superficial necrolysis and infiltration with lymphocytes. Treatment consists of removal of the tumor, if possible. Topical steroids may alleviate symptoms of the rash, but they do not clear it.

PRIMARY BLISTERING OR PUSTULAR INFECTIONS

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection is a common sexually transmitted disease manifested by recurrent, painful, grouped vesicles that quickly erode into superficial coalescing erosions.

Clinical Presentation

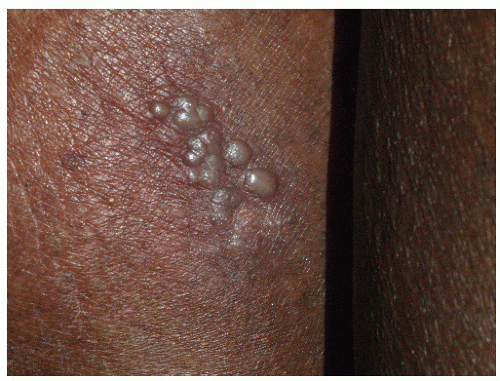

Most common in younger individuals, herpes simplex virus infection is especially likely in those who have higher risks of contagion due to many lifetime sexual partners. HSV produces both primary and recurrent infections. Primary infection with HSV is often subclinical and unrecognized, but the classic primary infection by HSV is much more severe than recurrent episodes. Primary genital HSV infection follows exposure by 2 to 7 days and often exhibits associated fever, malaise, headache, and other constitutional symptoms. Regional lymphadenopathy is usual; pain and edema may cause urinary retention. The lesions initially occur as small (1- to 3-mm), scattered, and grouped vesicles occurring typically on the glans or shaft of the penis or the mucous membrane and modified mucous membrane portion of the vulva, sometimes extending to keratinized skin (Figs. 9-19, 9-20 and 9-21). Because the vesicles are fragile and easily break, well-demarcated, discrete, round, and arcuate erosions (which indicate coalescing of the round erosions) often are seen rather than intact vesicles, especially on modified mucous membrane skin (Figs. 9-22, 9-23 and 9-24). Healing may be complicated by secondary infection and irritation from overwashing or topical agents used empirically by an anxious patient.

After a primary infection, HSV remains latent in neuronal cells located in ganglia. Subsequently, the virus intermittently reactivates, thus producing recurrent disease that is usually milder and shorter in duration. Recurrent genital HSV infections are less painful, more localized, and less often associated with fever, arthralgias, and headache than primary disease. Many patients experience

a prodrome of tingling, burning, or dysesthesias before the onset of skin lesions. Recurrent HSV is most often located on the glans and shaft of the penis and the mucous membranes and modified mucous membrane portion of the vulva, but can occur on any epithelial surface, including the scrotum, perianal skin, and hair-bearing labia majora. Recurrent episodes are characterized by grouped vesicles that quickly develop into well-demarcated, round, and arcuate erosions. On dry, keratinized skin such as the shaft of the penis or the hair-bearing labia majora, round crusts may be the predominant lesion. Linear fissures can appear as a manifestation of HSV infection, occurring most often in skin folds, such as the interlabial sulci of the vulva or within normal skin wrinkling of the penile shaft.

a prodrome of tingling, burning, or dysesthesias before the onset of skin lesions. Recurrent HSV is most often located on the glans and shaft of the penis and the mucous membranes and modified mucous membrane portion of the vulva, but can occur on any epithelial surface, including the scrotum, perianal skin, and hair-bearing labia majora. Recurrent episodes are characterized by grouped vesicles that quickly develop into well-demarcated, round, and arcuate erosions. On dry, keratinized skin such as the shaft of the penis or the hair-bearing labia majora, round crusts may be the predominant lesion. Linear fissures can appear as a manifestation of HSV infection, occurring most often in skin folds, such as the interlabial sulci of the vulva or within normal skin wrinkling of the penile shaft.

FIG. 9-20. This example of recurrent sacral herpes simplex virus infection shows the classic presentation of grouped vesicles occurring after a prodrome of burning or itching. |

FIG. 9-21. Any blister develops a pustular appearance after several days; this does not signify bacterial infection, and the fluid remains clear when the blister is punctured. |

The primary episode of HSV infection for many patients is subclinical, so these people do not experience a classic primary episode of HSV infection and are thus unaware of their infection. Thus, their first clinical episode of infection exhibits the localized grouping of vesicles and

erosions and milder clinical course of recurrent HSV infection. Because the appearance of this nonprimary but first clinical episode is delayed, the time and circumstances of transmission cannot be determined; on occasion, this delay is years long.

erosions and milder clinical course of recurrent HSV infection. Because the appearance of this nonprimary but first clinical episode is delayed, the time and circumstances of transmission cannot be determined; on occasion, this delay is years long.

FIG. 9-23. Uncircumcised men with herpes simplex on the fragile glans generally never see clinical blisters, but only erosions. |

HSV infections often are associated with marked morbidity in immunosuppressed patients (see Chapter 16). Patients with altered cellular immunity, as occurs in those with HIV disease and patients receiving immunosuppressive agents, are at increased risk of ulcerative and chronic HSV infection (Fig. 9-25).

FIG. 9-24. When herpes vesicle rupture, the original blistering nature is recognized by the round, coalescing nature of the erosions. |

Diagnosis

Although the diagnosis usually can be made on the appearance of skin lesions and history, laboratory confirmation of a genital HSV infection is desirable because of the psychologic impact of this disease on the patient and his or her partner. A viral culture from a swab of the base of a fresh erosion is the most common means of detecting HSV. However, false-negative results are a common occurrence in many laboratories, especially when delivery of the sample to the laboratory is delayed. Therefore, a negative culture should not convince a suspicious clinician to eliminate the diagnosis. Recently, the extremely sensitive polymerase chain reaction technique for detecting HSV has become widely available and reasonably priced, so this is now a test of choice (21). Although more uncomfortable, a shave skin biopsy from the edge of an erosion or of an intact vesicle is another very sensitive test to confirm the presence of a herpes virus infection, but a biopsy does not differentiate HSV from VZV. The Tzanck’s preparation, although very quick, is less reliable, even in experienced hands. Direct immunofluorescent antibodies are available for HSV1 and 2 for more rapid diagnosis, although an adequate sample is of utmost importance. Scraping the base of the ulcer with a number 15 blade usually suffices for an adequate cell sample. Serology is not an adequate means of diagnosing an episode of HSV. Positive IgG for HSV varies very widely according to the country, occurring in up to 80% of adults; this denotes exposure, but not active or communicable disease (22). Negative serology indicates no past infection, but does not rule out a primary episode, since about 6 weeks is required for conversion.

The histologic appearance of HSV includes an intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis formed by acantholysis. Individual keratinocytes show intracellular edema (ballooning) and reticular degeneration (intracellular edema causing cell walls to burst). Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies may be present. Multinucleated keratinocytes are pathognomic for herpes virus infections but do not distinguish between HSV and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections.

HSV must be differentiated from several other vesicular and pustular diseases. Occasionally, the differentiation of genital HSV infection from VZV infection can be difficult, because both exhibit grouped vesicles or erosions. However, genital VZV infection usually occurs in the older patient and covers a dermatomal pattern, also affecting the medial thigh or buttock unilaterally. VZV infection occurs only once in the immunocompetent patient, rather than recurrently, as is usual with HSV infection. Another likely disease to confuse with genital HSV infection is candidiasis of the modified mucous membranes of the vulva or the uncircumcised glans penis, in which yeast can cause coalescing erosions when superficial pustules rupture. A fungal smear is positive in that case. Folliculitis, both irritant and staphylococcal, produces discrete red papules and pustules that can mimic HSV. Finally, blistering erythema multiforme both mimics and sometimes follows HSV infection. The most common cause of recurrent erythema multiforme is recurrent HSV infection in a patient with an enhanced immunologic response to this virus. These patients usually exhibit both intraoral and genital erosions that are less well demarcated, whereas HSV does not occur inside the mouth, except for the initial primary outbreak. In addition, the occurrence of red, nonscaling, flat-topped papules on the palms, soles, and sometimes other keratinized surfaces is common.

Pathophysiology

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2 are doublestranded DNA viruses (Herpesvirus hominis) capable of producing vesicular and erosive mucocutaneous disease. Oral mucocutaneous and ocular disease is produced by HSV 1 in most cases, whereas genital HSV infection is caused by HSV 2 in the majority of affected patients. The proportion of HSV 1 occurring on the genital skin is increasing, presumably due to the increase in oral-genital sexual activity.

Management

The management of HSV infection begins with the sensitive and nonjudgmental education of the patient. The patient should be counseled regarding the infectious nature of the disease, its recurrent nature, and the importance of avoidance of sexual intercourse when open lesions are present. Circumcision and condoms have been shown to confer modest protection from infection (23,24). Patients should be aware that intermittent shedding of the virus occurs when there is no evidence of active HSV infection, and the infection can be transmitted even in the absence of blisters and erosions. In fact, most HSV infection is contracted during asymptomatic episodes. This shedding has also been documented in patients receiving long-term suppressive antiviral medication. Therefore, the use of a condom, even when there are no obvious lesions, is wise. The possibility of transmission of HSV to a newborn during delivery should be discussed to ensure the protection of future infants from maternal infection, although most neonatal HSV infections occur due to maternal primary infection.

Both primary and recurrent primary HSV infections are shortened by prompt treatment with specific oral antiviral agents, although some recurrent episodes are so mild that therapy is unwarranted. Three current choices for the treatment of recurrent HSV are as follows: 5 days of acyclovir 200 mg five times a day (or, for primary HSV infection, for 10 days), famciclovir 125 mg twice daily, and valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily (1 g twice daily for 10 days for primary HSV infection). These therapies exhibit equivalent efficacy, with choices made on the basis of cost and convenience of dosing. Side effects are minimal with each. Topical acyclovir exerts only minimal benefit. More recently, topical penciclovir has become available to shorten the course of HSV infection, but the benefit over placebo is minimal.

Intravenous acyclovir is occasionally needed if disease is severe, especially if the patient is immunosuppressed or if gastrointestinal absorption is a major problem, as can occur in the HIV-positive patient. Resistance of HSV to currently available oral medications occurs only occasionally and always in immunosuppressed patients. Foscarnet is an alternative treatment, although it is available only for intravenous use. Several other agents have been reported as beneficial in acyclovir-resistant HSV, including intravenous and topical cidofovir, topical trifluorothymidine, topical interferon-α in dimethyl sulfoxide, and imiquimod (25).

For patients experiencing frequent or severe episodes of HSV infection, chronic prophylactic acyclovir at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, famciclovir 250 mg twice daily, or valacyclovir 500 to 1000 mg/day is a safe, practical, and effective means of preventing most recurrences. Suppressive oral antiviral therapy also decreases asymptomatic shedding and, therefore, probably infectivity, but asymptomatic shedding of virus is not eliminated (26). Transmission of HSV infection still occurs in patients taking these medications and experiencing no clinical outbreaks.

Crucial to the management of anogenital HSV infection is counseling and psychological support. These patients exhibit marked anxiety, depression, fear, and selfesteem issues (27).

Herpes Zoster Infection (Shingles)

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes two diseases: herpes zoster, or shingles, and chicken pox. Both affect the genitalia but present very differently. The first episode of VZV (varicella, chicken pox) presents with generalized distribution of discrete red papules, vesicles, and crusts, but there is a predilection for the genital skin and vagina. Shingles, the second episode of VZV is localized, typically very painful, and with minimal constitutional symptoms. Hopefully, with the availability of the shingles vaccine, this condition will become uncommon.

Clinical Presentation

Herpes zoster occurs primarily in patients with immune deficiency by virtue of age, disease, or medications, but occasionally occurs in young and healthy individuals. The prevalence of this miserable condition should decrease as more older people receive the recently available vaccine.

Many patients experience a localized prodrome of pain, itching, burning, or aching, followed in one or a few days by pink, nonscaling plaques in a unilateral dermatomal distribution (Figs. 9-26 and 9-27) in the symptomatic area. Grouped vesicles overlying these red plaques quickly follow, then coalesce into larger blisters. Often, the blisters become purple or gray due to hemorrhage into the blister. Over the next 3 weeks, the blisters crust and heal. Blisters occurring on mucous membranes and modified mucous membranes of the genitalia are quickly unroofed due to friction on this moist and very thin skin, so that erosions usually predominate. Likewise, the friction from skin folds and clothing often tears blister roofs even on the more keratinized genital skin. Herpes zoster can become ulcerative, chronic, or hyperkeratotic in immunosuppressed patients (see Chapter 16).

FIG. 9-26. Herpes zoster is characterized by red plaques of clustered vesicle that are unilateral and in a dermatomal distribution. |

FIG. 9-27. In addition to the one-sided nature of the blisters of herpes zoster, patients with herpes zoster, unlike those with herpes simplex, do not experience recurrences. |

Sometimes, the eruption is accompanied by mild headache, malaise, and a low-grade fever. However, the primary complication of herpes zoster infection is the development of postherpetic neuralgia, in which chronic pain persists after the eruption resolves. This is more likely in individuals over 60 years of age and in immunosuppressed people. Some clinicians theorize that this may be responsible for some genital pain syndromes such as vulvodynia and scrotodynia, but preceding VZV infection affecting the genitalia is almost never identified in patients with genital pain syndromes. Unlike HSV, VZV does not recur in immunocompetent patients.

Diagnosis

The definitive diagnosis of herpes zoster is usually made on the basis of the presentation and morphology. When necessary, this can be confirmed by a positive culture or the identification of viral DNA with the PCR technique. The virus is rather fastidious, so cultures are sometimes falsely negative, but the PCR technique is very sensitive and now easily available. Tzanck’s preparation from epithelial cells scraped from the base of a blister or erosion shows giant cells when examined microscopically, but the validity of this test is extremely dependent on the examiner, and the results are subjective. A biopsy is extremely sensitive but does not differentiate between HSV infection and herpes zoster, a distinction that can usually be made on clinical grounds. The histologic appearance of herpes zoster infection is identical to that of HSV infection. Keratinocytes swell and burst, and some epithelial cells form giant cells. Occasionally, leukocytoclastic vasculitis underlies these epithelial changes, but this does not indicate a primary or possibly systemic problem of vasculitis.

The differentiation of genital herpes zoster infection from HSV infection may be difficult. HSV is a recurrent disease, whereas herpes zoster is a one-time event, except in significantly immunosuppressed patients. Herpes zoster is unilateral, but vesicles may erode early in both diseases. Bullous impetigo and bullous pemphigoid can sometimes mimic herpes zoster, but these are usually bilateral and are not particularly painful. Bullous pemphigoid generally exhibits distant lesions that exclude the diagnosis of herpes zoster, and impetigo can be differentiated by culture.

Pathophysiology

Herpes zoster infection is a blistering disease that results from reactivation of VZV that has been latent in nerve ganglia since a remote episode of varicella. This condition occurs most often in older individuals whose immune system is less efficient or in immunocompromised patients.

Management

For most patients with herpes zoster, pain control is the most important aspect of care. Narcotic pain analgesia is usually needed for the first few weeks. The early diagnosis and treatment (within 72, but especially 48 hours) with oral antiviral therapy somewhat reduces the duration of an acute infection. This improvement is not striking, so therapy is optional in younger, healthy patients. However, immunosuppressed or very elderly people should be treated. Some studies have shown an arguably significant reduction of postherpetic neuralgia in patients treated early.

Choices include acyclovir 800 mg five times a day, famciclovir 500 mg three times daily, and valacyclovir 1 g every 8 hours. The advantage of the more expensive valacyclovir and famciclovir is the less frequent dosing schedule.

Those patients who experience postherpetic neuralgia deserve medication for neuropathic pain, including amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, venlafaxine, or duloxetine (see Chapter 5). Sometimes, referral to a pain clinic is necessary.

Otherwise, the best current management is prevention. A vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster is now available, approved by the Food and Drug Administration for people over 60 years of age.

Candidiasis

Vaginal and vulvar infection with Candida albicans is common, but genital candidiasis in men is essentially confined to uncircumcised, incontinent, obese, or immunosuppressed men (see also Chapters 4, 8, 11, 14, and 15). Although genital Candida albicans infection is most often erythematous and scaling (see Chapter 3), severe disease sometimes produces erosions. Women present with vaginal discharge, itching, and soreness of the vulva. Erythema, scale, and pustules that shed blister roofs and form coalescing superficial erosions are seen (Figs. 9-28, 9-29 and 9-30). At the edge of eroded plaques are satellite pustules that erode into collarettes and round erosions. In addition, Candida albicans often produces linear erosions, or fissures, in the skin creases between the labia

minora and labia majora. In men, candidal balanitis and intertrigo present with burning and itching, and with papules and pustules that merge to form eroded plaques. Predisposing factors for external and intertriginous genital candidiasis include diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid therapy, pregnancy, treatment with oral contraceptive pills or broad-spectrum antibiotics, an infected sexual partner, and immunosuppression. Local moisture and obesity also contribute.

minora and labia majora. In men, candidal balanitis and intertrigo present with burning and itching, and with papules and pustules that merge to form eroded plaques. Predisposing factors for external and intertriginous genital candidiasis include diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid therapy, pregnancy, treatment with oral contraceptive pills or broad-spectrum antibiotics, an infected sexual partner, and immunosuppression. Local moisture and obesity also contribute.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree