Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures

Libby Edwards

The evaluation and diagnosis of anogenital diseases are a process that generally requires only a limited history, careful observation, and minor office procedures. Although there are several diagnostic procedures useful for the diagnosis of anogential procedures, the crucial aspects of evaluation are a careful visual examination, microscopy of vaginal fluid and some scaling skin conditions, and, at times, skin biopsy. The careful inspection of the skin requires a good light and, sometimes, simple magnification. The degree of magnification afforded by a colposcope is not required (1).

At times, the diagnosis of skin disease on the genitalia is obvious, with classic signs. However, the typical morphology of skin disease often is modified in the folds of genital skin, where the skin is often normally somewhat red, and where moisture, heat, and friction obscure scale and change the appearance of dermatoses. For those diseases that display objective abnormalities, the cause is nearly always infection, tumor, or noninfectious inflammation that is often immune mediated. Even when the exact diagnosis cannot be ascertained by examination or biopsy, infection and tumor can be ruled out by cultures and biopsies (Table 3-1). Those remaining diseases are categorized by the histologic description (see Appendix 1), and correlated with physical findings to generate a differential diagnosis. Most visible skin disease that is not tumor or infection is corticosteroid responsive. Sometimes a definitive diagnosis cannot be made, and when easily diagnosed and dangerous conditions have ruled out, presumptive therapy is reasonable and often beneficial.

Treatment of skin diseases is often time-consuming, because careful and sensitive patient education generally is required, and attention to multifactorial processes such as secondary infection and irritant contact dermatitis is important. Except for radiation therapy and the surgical removal of growths, the therapy of most genital disorders is medical, consisting of self-administered oral and topical medications. There are several office procedures, however, including intralesional therapy, cryotherapy, and the application of topical chemotherapy such as trichloroacetic or bichloroacetic acid, phodophyllum resin, or cantharidin.

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

In genital dermatology, most diagnostic procedures are performed in an outpatient setting or at the bedside. Required are only a microscope, glass slides and coverslips, 10% to 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH), and normal saline. Although these procedures are easy to perform, the interpretation of the microscopic findings requires extensive experience. Unexpected results or poor response to therapy should be followed by cultures or biopsies to corroborate the microscopic findings. Clinicians who care for patients with vulvar dermatoses or vulvar pain should invest in a narrow, straight Pederson speculum, which produces far less distention of the introitus and less pain on insertion than does the standard Graves speculum with its bulbous tip. However, visualization of the cervix is much more difficult with the Pederson speculum. The use of a speculum allows for visualization of the vaginal walls and sampling of vaginal fluid for microscopic examination and culture. Occasionally, biopsy specimens are obtained and sent to the laboratory for histologic evaluation. When biopsies are performed, the most likely diagnoses should be indicated on the pathology requisition, to provide the pathologist with information and to narrow the clinically possible diagnoses. Often, the “diagnosis” on the final laboratory report is a microscopic description (see Appendix 1) rather than a specific disease name, so that correlation of this description with the appearance of the skin is required to formulate the most likely diagnosis. Sometimes, one firm diagnosis is not possible, but possibilities can be narrowed to allow for initiation of therapy.

Cytologic Smears

Fungal Preparations

Fungal preparations are essential to the diagnosis of anogenital disease. Men generally interpret all anogenital itching as produced by “jock itch,” or tinea infection, whereas women assume all vulvovaginal itching to result from candidiasis. The confirmation or elimination of these conditions is vital.

TABLE 3.1 Diagnosis of unknown skin disease | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KOH 10% to 20% solution is a basic agent that dissolves the keratin of epithelial cells, allowing spores and fungal hyphae and pseudohyphae to be seen more clearly. The reliability of this test depends on the choice of the lesion to be sampled, adequate dissolution of cells so fungal elements are best visualized, and the experience of the examiner in distinguishing fungal elements from artifacts such as hair, fabric fibers, cell membranes, and fractures in crusts.

The specimens most likely to yield fungi include the peripheral scale from plaques of possible dermatophyte infection, pustule roofs, and white, cheesy material produced by suspected yeast. These elements are removed by scraping with the rounded surface of a number 15 scalpel blade. In the damp areas of the genitalia, the sample usually adheres to the scalpel blade and can be wiped onto the glass slide. Dry, hairbearing skin can be moistened with water so that the moistened specimen sticks to the blade until it is smeared onto the slide. Vaginal secretions are collected with a cotton-tipped applicator from secretions remaining on the blade of the withdrawn speculum, from a pool of secretions within the vagina (avoiding the cervical os) or by gently rolling the cotton tip along the vaginal walls.

Once the specimen is applied to the glass slide, a drop of KOH is placed on the material to dissolve the keratin from cells and to enhance the visibility of fungal elements. A coverslip is applied, and firm pressure to the coverslip with the back of a fingernail or a pencil eraser (to avoid distracting fingerprints on the coverslip) flattens and augments the dissolution of keratin. Although the unkeratinized epithelial cells in vaginal smears deteriorate quickly after exposure to KOH, the scale of keratinized skin requires further attention to dissolve so that fungi and yeasts can be easily detected. The examiner can use KOH mixed with dimethylsulfoxide to enhance dissolution or can simply allow 10 to 15 minutes for the KOH to disintegrate the cells. In addition, gentle warming of the specimen over an alcohol flame dissolves cells from keratinized skin more quickly.

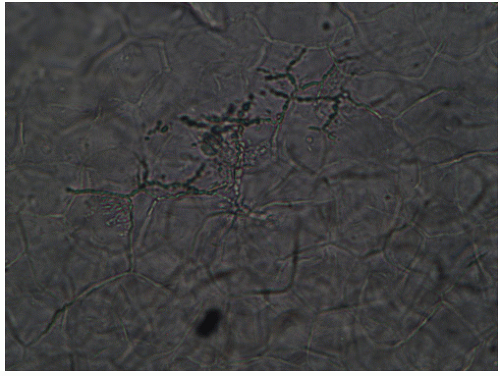

FIG. 3-1. Dermatophytosis of tinea cruris shows hyphae similar to candidiasis, but there are no budding yeast; the hyphae are long, branching, and cross cell membranes. |

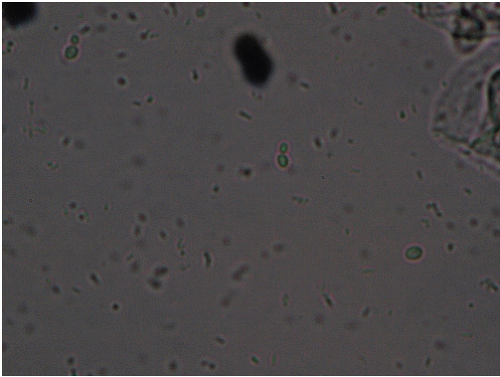

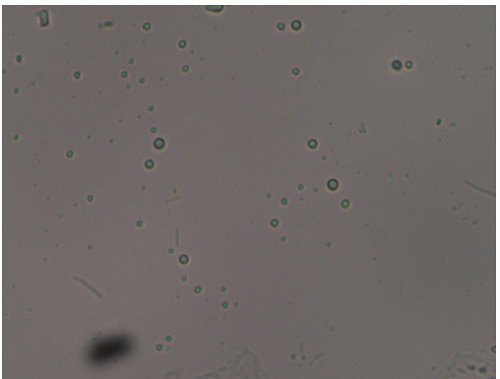

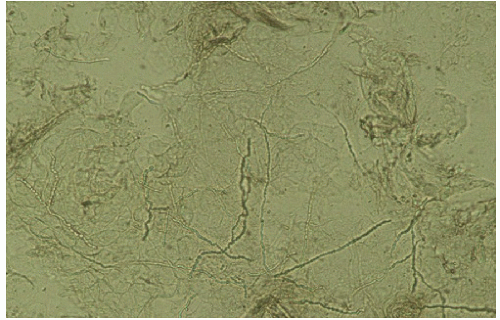

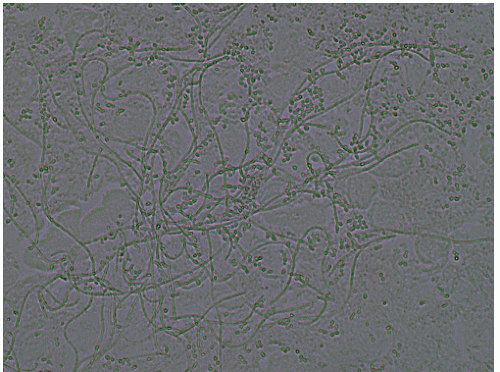

Fungal elements are best visualized by lowering the condenser and decreasing the light to increase the contrast between fungi elements and epithelial cells. Spores, buds, and hyphal elements appear refractile and sometimes very slightly green, and these are much smaller than common artifacts, such as hair and fibers. Dermatophytes appear as branching, septate hyphae that cross over cell membranes (Fig. 3-1). Candida appears as budding yeasts with or without hyphae or nonseptate, branching pseudohyphae (Fig. 3-2). At times, cell membranes in the process of dissolving resemble hyphae or pseudohyphae (Fig. 3-3). Pressure on the cover slip generally disrupts the cells and these partially dissolved membranes. The specific dermatophyte species cannot be recognized from the smear, and Candida species can be divided only into those characterized by hyphae or pseudohyphae (C. albicans or C. tropicalis) or yeast forms

that exhibit budding yeast only (e.g., C. glabrata or C. parapsilosis) (Fig. 3-4). A culture is required to confirm the species if needed. Oil droplets and air bubbles can be confused with yeast buds at times, but the variability in size and very round shape distinguish these from yeast buds (Fig. 3-5). “Tinea” versicolor (which occurs uncommonly in the genital area) is a misnomer because it is a yeast rather than a dermatophyte or “tinea.” It exhibits short, curved hyphae and spores/buds (“spaghetti and meatballs”) microscopically.

that exhibit budding yeast only (e.g., C. glabrata or C. parapsilosis) (Fig. 3-4). A culture is required to confirm the species if needed. Oil droplets and air bubbles can be confused with yeast buds at times, but the variability in size and very round shape distinguish these from yeast buds (Fig. 3-5). “Tinea” versicolor (which occurs uncommonly in the genital area) is a misnomer because it is a yeast rather than a dermatophyte or “tinea.” It exhibits short, curved hyphae and spores/buds (“spaghetti and meatballs”) microscopically.

FIG. 3-2. The hyphae and pseudohyphae of dermatophytosis and candidiasis are nearly indistinguishable, but on this higher power, budding yeast often can be seen in candidiasis. |

Saline “Wet Drop” Preparation (see also Chapter 15)

A microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions using normal saline under a coverslip permits an evaluation of the morphology of cells, a screen for inflammation and estrogen effect, and a crude survey of colonizing and infecting organisms. Information from an examination of vaginal secretions is sometimes extremely important in the evaluation of the vulva and vagina (Table 3-2). Secretions are collected as described above for evaluation for Candida spp. However, the secretions are transferred from the cotton tipped applicator by touching (if abundant) or gently rolling (if scant) onto the glass slide. Care should be taken to avoid the thick application of secretions, which interferes with visualization.

In order to evaluate vaginal secretions for abnormalities, the examiner should be aware of the ranges of normal (Fig. 3-6). Mature epithelial cells shed from a well-estrogenized vaginal epithelium appear as large, often folded, polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm and a small, condensed nucleus. A crude maturation index can be performed, in which the degree of maturation of epithelial cells is estimated. Immature epithelial cells, or parabasal cells, are much smaller and rounder than mature cells, with proportionately larger nuclei (Fig. 3-7). These less mature cells are seen in several settings and serve as a marker for atrophic, estrogen-deficient vaginal epithelium, erosions within the epithelium, and rapidly proliferative inflamed skin. Epithelial cells also appear abnormal in the setting of bacterial vaginosis and are pathognomonic for that condition. These clue cells occur when non Lactobacillus bacteria adhere to epithelial cells and obscure the sharp borders of the cells so that the edge appears ragged and the cytoplasm appears granular (Fig. 3-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree