Abstract

This chapter covers the various issues involved in soft-tissue reconstruction of the hand due to defects from various etiologies, such as trauma, tumor extirpation, thermal injuries, and infectious complications. The primary concerns of stable coverage, mechanical loading, pliability, sensation, and aesthetics are individually addressed. Diagnostic options for assessing injuries are listed and surgical techniques—skin grafts and local, regional, chest, and free flaps—are reviewed. Three case examples help illustrate the techniques presented, and seasoned advice on postoperative care and outcomes is provided.

25 Soft-Tissue Reconstruction of the Hand and Upper Extremity

25.1 Goals and Objectives

Help the reader learn the anatomy and functional needs of the hand that must be considered when planning soft-tissue reconstruction.

Identify the important information the reconstructive surgeon must gather to plan coverage.

Understand how the nature and site of the defect lends itself to various reconstructive options.

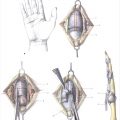

Comprehend the surgical technique for some of the more commonly used reconstructive modalities.

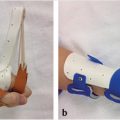

Know the appropriate postoperative regimen to improve outcomes for these reconstructive patients.

25.2 Patient Presentation

25.2.1 Hand Soft Tissue and Function

The hand is the most commonly injured part of the body; as such the surgeon who treats the hand is frequently asked to reconstruct soft-tissue injuries. Soft-tissue deficits of the hand arise from a variety of etiologies including trauma, tumor extirpation, thermal injuries, and infectious complications. The resultant defects can range from only localized skin loss to extensive exposure of tendons, joints, and bone with varying degrees of involvement of these structures. The goal of treatment is not only to provide soft-tissue coverage but also to restore optimal function and appearance. A reconstructed hand that is insensate and does not move is of little benefit to a patient. Limiting long-term sequelae of scarring and hypersensitivity is a priority. At the same time, patients now have a heightened awareness of aesthetic outcomes, and this has been shown to be an important factor in satisfaction of reconstruction. 1 , 2 , 3

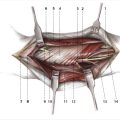

The hand has three anatomical structures that make reconstruction a unique challenge. First, the glabrous skin on the volar surface is thicker and has a higher density of sensory end organs than does most skin. Second, the vital structures of the hand are padded by a layer of mechanical fat directly beneath the skin. This adipose tissue has smaller globules, more fibrous tissue, and is tethered to its position, thereby absorbing force and resisting migration. Third, the palmar fascia holds the overlying skin and mechanical fat in place with multiple fibrils which allows the hand to grip firmly and resist shear stress.

Ideal reconstruction of these structures when missing provides stable coverage, allows mechanical loading, does not restrict movement, provides protective sensation, and does not draw visual attention to itself, all with minimal donor-site morbidity (Table 25‑1). Achieving all these goals can be challenging; however, attention to the primary treatment effort will help avoid the need for later complex procedures to treat unstable wounds, painful function, or scarred coverage. In addition, the choice of treatment must be practical for the patient and this will vary based on culture, age, and patient demographics such as smoking. The same defect presenting in a young female with high aesthetic goals could be managed differently than in an older male manual laborer. Technically demanding retrograde facial flaps in smokers have higher failure rates and poorer outcomes. Thus, the reconstructive choices for soft-tissue defects of the hand and upper extremity must take into account all of these variables.

From the aforementioned information, the wide range of possible defects, multiple goals that must be achieved, and numerous patient considerations combine to make standardized cookbook approaches to hand soft-tissue deficits limited in their applicability. This chapter aims to provide the reader with practical options that offer reliable outcomes. The reconstructions described are a way to address the challenge and demonstrate the applicability of a specific technique. More important is to see how the surgical choice addresses the underlying needs of the hand within the parameters of a particular patient. Each surgeon will develop his or her own algorithm and tools to manage their particular patient population.

25.2.2 Evaluation of the Patient

Clinical Presentation

Patients with hand and upper extremity soft-tissue deficits can present in both an urgent or elective manner based on their etiology. The mechanism of soft-tissue loss should be described as precisely as possible as it may give information as to the extent of the deficit and potential reconstructive needs. The history may include symptoms of pain, loss of extensor or flexor function, joint or bone instability, and/or sensory disturbance. Questions should also be answered regarding any previous trauma or functional deficits, prior radiation, and functional demands the patient places on the hand.

During the initial evaluation, a surgeon has the advantage of temporizing care with dressings until formal evaluation of the defect is made and a reconstructive plan can be agreed upon with the patient. The primary means of evaluating the deficit is by a thorough motor and sensory exam including tissues proximal and distal to the zone of injury. The exam should note the surface area of soft-tissue loss as well as the location, paying particular attention to joint creases that are involved. Depth and degree of involvement of the glabrous skin, mechanical fat, and palmar fascia should also be assessed and documented (Table 25‑2).

25.3 Preparation for Surgery

25.3.1 Diagnostic Adjuncts

Standard 3 view radiographs are obtained for all patients with traumatic etiology. These are also used selectively in tumor extirpation, thermal injuries, and infectious complications as there may be bone involvement. Other imaging modalities such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography may be of value in select cases where bone reconstruction may accompany soft-tissue coverage or free tissue transfer is being considered. Photographic documentation of the original and subsequent examinations is helpful for providing a more objective basis for comparisons over time and among providers.

In large traumas where significant blood loss was encountered, a hemogram may be valuable if large immediate reconstructive efforts are planned. As the time from creation of the defect to planned reconstruction increases, a nutrition workup including albumin and prealbumin is indicated to ensure the patient will be able to heal after the surgery.

25.4 Treatment

25.4.1 Anatomic Classification

Understanding the anatomic nature of the defect and its location will provide the surgeon the key elements in choosing an appropriate reconstructive option for soft-tissue coverage of hand and upper extremity defects. Table 25‑3 describes four anatomic sites or zones of injury requiring soft-tissue reconstruction. Alternatives for care for each of these sites are listed in the right column. The actual reconstruction chosen will depend on the volar or dorsal nature of the defect as well as the degree of tissue loss.

Specific Considerations

Secondary Intention

For most skin-only tissue loss, particularly those wounds 1 to 2 cm2 or less and not involving a volar joint crease, allowing the wound to heal by secondary intention is a good option. The resultant scar is sufficiently durable for long-term function, and the contracture pulls normally sensate skin into the area. This is particularly a useful way to treat volar zone 1 injuries.

The patient is instructed to wash the wound twice a day with plain soap and water (hydrogen peroxide should be specifically prohibited as many people habitually use it on open wounds of the hand). The wound is then dressed with antibiotic ointment and a nonadherent dressing. Most wounds should close within 2 to 3 weeks.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree