Facial trauma accounts of 7% to 10% of emergency department visits in the United States every year. The management of facial soft tissue trauma is an essential skill for the facial plastic surgeon. Understanding preoperative evaluation, repair/management of concomitant injuries, postoperative care, and scar treatment help the facial plastic surgeon obtain the best functional and aesthetic results for the patient. Treating the face by subunit and avoiding common pitfalls is the key to achieving optimal results. This article can serve as a basis for surgical pearls and considerations when evaluating and repairing facial soft tissue trauma.

Key points

- •

Adequate preparation and timely treatment of facial wounds is integral for an adequate functional and cosmetic result.

- •

Understanding surgical pearls for each specific facial subunit will help avoid pitfalls and poor results when planning and repairing facial soft tissue trauma.

- •

Otolaryngologist referral and management of auricular hematomas is essential to avoiding recurrence and complications such as cauliflower ear.

- •

The best scar revision techniques are not as efficient as initial injury repair with the eversion of skin edges, avoiding tension on the wound, lining up key landmarks, and closing the wound in layers.

Introduction

Facial trauma is among the most common craniofacial chief complaints encountered in emergency departments every year in the United States. These incidents account for nearly 7% to 10% of all emergency department visits annually. , Although the leading cause of facial soft tissue trauma is motor vehicle accidents, other causes include athletics, industrial accidents, self-inflicted trauma, falls, assault, and bites. , This population accounts for nearly 150,000 visits per year in emergency departments across the United States. , The complexity of facial soft tissue repair arises from its many functional and aesthetic subunits and the long-lasting implications related to a patient’s countenance.

Initially, patients with facial trauma should be evaluated for life-threatening injuries following Advance Trauma Life Support Guidelines, as facial soft tissue trauma can cause significant bleeding, potential airway compromise, or significant vascular injury.

History/initial evaluation

When evaluating facial injuries, the history of the injury and mechanism is integral to successful repair. Mechanisms such as falls, motor vehicle accidents, or gunshot wounds necessitate thorough examination for foreign material since foreign bodies impair wound healing. Bite injuries increase the risk of infection due to their polymicrobial nature and may require prophylactic antibiotics or tetanus prophylaxis. A visibly infected wound, usually from delayed presentation, will require therapeutic antibiotics, often directed by a culture. Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for bite wounds or wounds with foreign material exposure and are not indicated for clean injuries. , Tetanus prophylaxis with a diphtheria-tetanus booster is indicated in those with a clean/minor wound and unknown tetanus history or less than 3 doses. In tetanus prone wounds, unknown/under vaccinated individuals receive both the booster and tetanus immunoglobulin. Tetanus prone wounds include bite wounds/punctures, presence of significant devitalized tissues, burns, associated sepsis, contact with soil/manure, or delayed surgical intervention (past 6 hours). Those with 3 or more doses that are up to date with boosters receive no prophylaxis in clean wounds. If they are not up to date with boosters, patients with dirty wounds receive tetanus immunoglobulin. The patient’s complete past medical history should be obtained. A history of diabetes, radiation therapy, alcohol abuse, or smoking has been shown to inhibit wound healing and should be noted. , Preoperative photographs and inquiring about prior craniofacial surgeries or functional deficits help restore the patient to premorbid status and set realistic expectations. The use of blood thinners or medications that inhibit healing such as immunosuppressives should also be noted.

Physical examination

Following the history, a thorough physical examination is integral. Serious injuries should be addressed before focusing on the wound and reconstructive plan. Ophthalmologic injuries or visual changes require urgent ophthalmology consultation. CT imaging should be obtained if malocclusion, palpable fracture lines, or structural instability is noted. Mental status should also be assessed. One study found that with any element of impaired consciousness, an age greater than 60 years, or symptoms including headache, nausea, and vomiting, CT imaging of the brain is necessary due to the higher likelihood of a concomitant neurologic/brain injury. ,

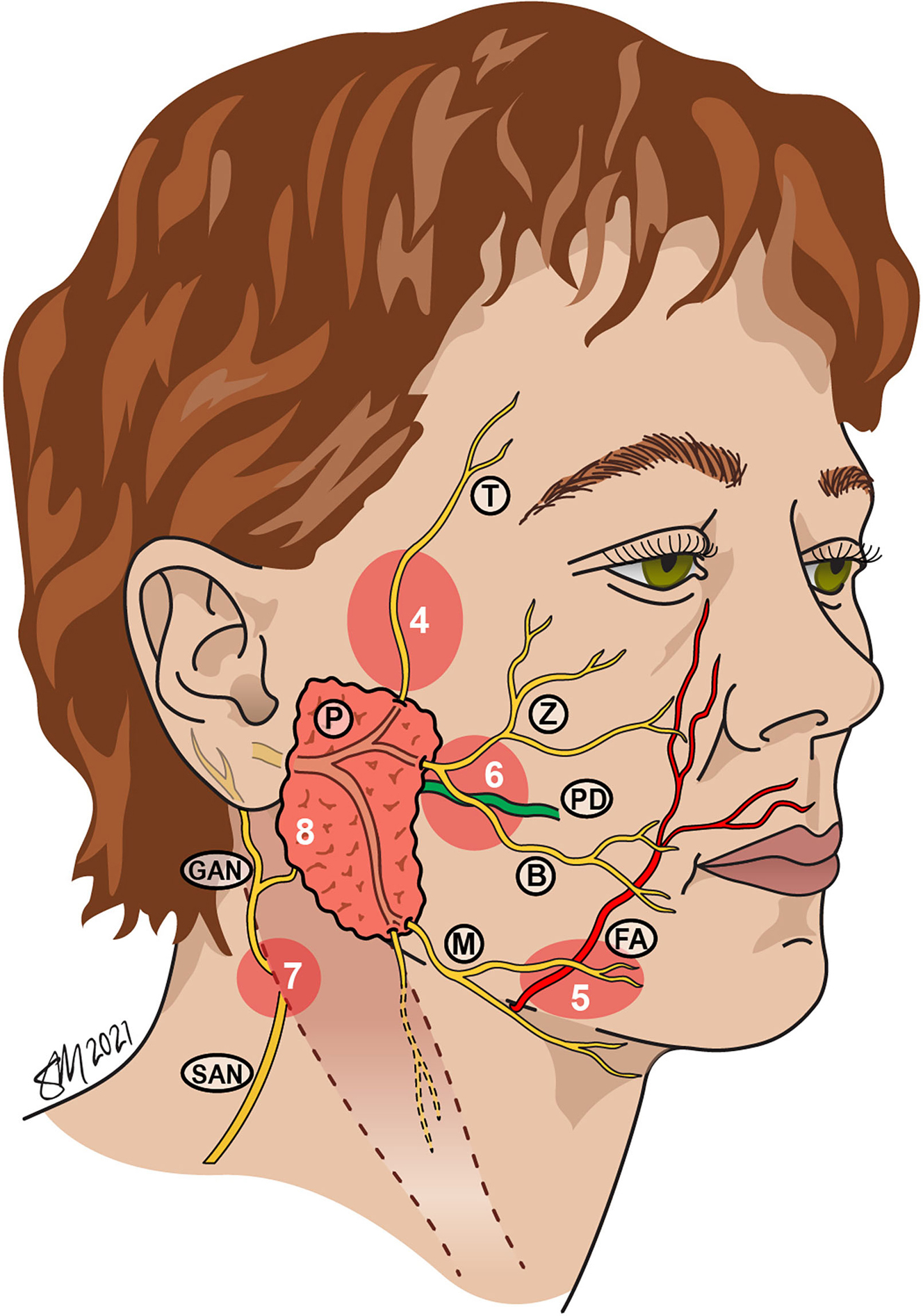

After the initial survey and physical examination, the soft tissue injuries are analyzed. The facial nerve, trigeminal nerve, and parotid duct (PD) integrity should be confirmed. If the patient is conscious, a House-Brackman score of 1 to 6 should be documented and laterality noted. More specifically, the upper, middle, and lower divisions of the nerve should all be documented separately to help localize the injury. Fig. 1 depicts danger zones of the face that should increase suspicion for possible structural damage that may need repair. In the absence of an injury to these specific areas, paralysis or paresis could be due to edema. Complete and immediate paralysis of an area of the face coupled with a penetrating injury dictates immediate operative room repair. Immediate repair in such a scenario is easier than delayed repair. The distal nerve ends can often be stimulated with a nerve stimulator, and a neurorrhaphy can be performed after devitalized edges are trimmed. If there is minimal tension at closure, primary neurorrhaphy can be performed in an epineural or perineural fashion with the aid of microscopy with similar outcomes. This is usually performed with a monofilament, permanent, 8:0 to 10:0 suture. An interposition graft from the great auricular nerve (7 cm of length) or sural nerve (30 cm of length) has similar outcomes to primary neurorrhaphy. Because both are afferent nerves, the polarization should be marked and reversed for reconstruction. Facial nerve injuries distal to a vertical line drawn from the lateral canthus often do not need to be repaired due to anastomotic branches; however, the marginal mandibular branch and temporal branch have little crossover and intervention should be considered.

After facial nerve injury has been ruled out, the wound should be inspected for saliva. As seen in Fig. 1 , the PD travels 1.5 cm below the zygomatic arch, travels with the buccal branch of the facial nerve, turns medially at the border of the masseter, transverses the buccinator muscle, and eventually enters the oral cavity in the buccal mucosa adjacent to the second maxillary molar. If saliva is present in the form of bubbles or viscous fluid, a direct parotid injury could be present opposed to an injury to stensen duct. The distal end of the duct can be located intraorally and a small 22-gauge silastic stent can be placed to locate the tear in the duct or proximal end if suspected. This can be repaired over the stent with a nonabsorbable 4:0 or 5:0 suture; the stent can be sutured to the buccal mucosa and can be removed at 2 weeks. Alternatively, if this cannot be accomplished the proximal duct can be reimplanted into the oral cavity and/or can be ligated. More commonly, saliva present in a wound signifies a parotid gland injury that can be oversewn with a braided absorbable suture and treated with conservative management with a pressure dressing. Despite the aforementioned treatments, literature shows that conservative management is generally well tolerated, and immediate surgical repair is often unnecessary. , If attempted, the patient should go to the operating room for repair.

Wound inspection/Wound preparation

Soft tissue trauma consists of abrasions, contusions, lacerations, and avulsions. An abrasion is a superficial skin injury and should be dressed with antibiotic ointment and covered. A contusion is a deeper ecchymosis that should be examined for underlying hematoma or bony injury. If hematoma is present this should be aspirated and or drained followed by the application of a pressure dressing. A laceration involves a tear that goes through the epidermis and or dermis including possible injuries to deeper tissues. An avulsion is injury with tissue loss. Occasionally an avulsion can be repaired with primary closure but may require grafts, local flaps, regional flaps, or free tissue transfer.

The size, depth, and wound base status including the viability of the wound edges and presence of gross contamination or infection should be investigated. If the wound has foreign bodies, traumatic tattooing, is a bite wound, or has not been repaired within 6 hours, it is considered contaminated. A dirty wound should undergo high-pressure pulsatile irrigation or bulb syringe irrigations with saline or a mixture of 50,000 units of bacitracin in 1 L of saline. This cleansing can be performed after anesthetizing the wound with local field or regional blocks. In an animal model, both bulb and high-pressure techniques are successful at lowering the bacterial load in wounds; however, high-pressure pulsatile irrigation is 3 times as effective. Many practitioners irrigate all traumatic facial wounds before repair despite literature supporting no benefit in clean facial and scalp injuries. Realistically, a psi of 5 to 8 is accepted as adequate for cleansing traumatic wounds, making bulb irrigation sufficient.

Following irrigation of dirty wounds, devitalized tissue and irregular wound edges can be debrided conservatively. Devitalized tissue impairs the wound’s ability to heal and resist postoperative infection. , Extensive debridement can lead to tense wound closure and is often unnecessary due to the vast blood supply to the face. Although the wound should be prepped with povidone iodine or another similar agent, gently scrubbing the area with a high porous sponge has been found to be effective in decontamination and debridement of facial wounds without causing extensive tissue damage.

Surgical considerations

After the wound has been prepared and thoroughly examined, the setting of repair can be determined. Indications for operating room are as follows :

- •

Patient tolerance

- •

Complex tissue rearrangement

- •

Wounds under significant tension

- •

Patient age

- •

Concomitant injuries such as facial fractures or airway compromise

- •

Poor hemostasis or major vascular injury

- •

Facial nerve injury requiring repair

- •

PD injury requiring repair

- •

Prolonged operative time greater than 2 hours

If the patient meets none of the aforementioned criteria and is not a young child, repair should be performed as soon as possible in the office or emergency department setting, as expediency of treatment has been linked to better cosmetic outcomes. , Anesthesia considerations are included:

- •

1% lidocaine plain

- ○

Maximum dose 3 to 4 mg/kg

- ○

Rarely used because of lack of vasoconstrictive properties

- ○

Analgesic onset less than 2 minutes

- ○

Duration 1.5 to 2 hours

- ○

- •

Lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1:100,000

- ○

Maximum dose 5 to 7 mg/kg

- ○

Commonly used due to vasoconstrictive properties

- ○

Analgesic onset less than 2 minutes

- ○

Vasoconstrictive onset 10 to 15 minutes

- ○

Duration 2 to 6 hours

- ○

- •

Bupivacaine 0.25%

- ○

Maximum dose 2.5 mg/kg

- ○

Analgesic onset less than 2 minutes

- ○

Duration 2 to 4 hours

- ○

- •

Ketamine

- ○

Often used in pediatric populations in the emergency department

- ○

- •

EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) cream

- ○

Often used in the pediatric population to limit the need for local infiltration

- ○

Found to decrease the need for local anesthesia infiltration by 85% in extremity laceration repair

- ○

- •

Monitored anesthesia care

- ○

Propofol

- ○

Versed and fentanyl

- ○

Used for shorter complex repair

- ○

- •

General anesthesia

- ○

Reserved for longer, complex repairs involving deeper or concomitant injuries

- ○

Many avoid the use of lidocaine with epinephrine in areas such as the ear and the nose for fear of necrosis and tissue compromise. The evidence supporting such complications is anecdotal and as long an intravascular injection is avoided, vasoconstrictive agents are safe in any area of the face, scalp, and neck. Regional blocks should be used for larger injuries and avoid tissue distortion; however, they do not provide sufficient local vasoconstriction. Local field blocks are superior for smaller lacerations or injuries, especially when hemostasis is a major concern as in most areas of the face.

Surgical technique

For an aesthetically satisfactory result, there are many key principles that should be followed for laceration repair. These key principles are listed here. Specific considerations are addressed in each facial subunit section.

- •

Generously undermine surrounding tissues to avoid trap door deformity from lymphatic disruption.

- •

Gently handle tissues with skin hooks and toothed forceps to avoid crush injury.

- •

Minimize tension with layered closure. Approximate the wound with absorbable inverted suture material deep (3–4:0 Monocryl, PDS, or Vicryl).

- •

Mucosal injuries should be closed with 3 to 5:0 absorbable suture (chromic).

- •

Permanent 5 to 6:0 nylon or prolene on the epidermis.

- •

Avoid complex repair, at least initially, if primary closure will suffice.

- •

Ensure adequate eversion of skin edges to avoid step-offs.

- •

Consider vertical mattress suture technique when eversion is difficult.

- •

Skin sutures should line up epidermis without strangulating the wound edges to avoid track marking.

- •

Long lacerations can be closed in running fashion; shorter lacerations can be closed with simple interrupted sutures.

- •

Consider subcuticular closure or absorbable sutures for superficial closure in children to avoid suture removal.

Perioperative/postoperative management

Antibiotics in the perioperative/postoperative period should be considered for mucosal wounds; contaminated wounds; bite wounds; delayed closure; and in patients with diabetes, immunocompromise, alcoholism, malnutrition, smoking, or other factors known to affect wound healing. Anaerobic coverage is necessary for bite wounds. A period of 7 days is usually adequate. Keeping the epidermal layer closure clean of crusts with hydrogen peroxide and moist with antibiotic ointment has been shown to improve/expedite wound healing. Patients with allergies to topical antibiotics can apply petroleum jelly–based products, and this is equally effective to antibiotic ointment. Sutures are generally removed in 5 to 7 days.

Special considerations by facial subunit

The following sections discuss general principles for each facial subunit as well as surgical pearls.

Scalp/Forehead

- •

Layers of scalp from superficial to deep: skin, connective tissue, aponeurotic tissue (galea), loose areolar tissue, pericranium

- •

Scalp defects less than 3 cm can generally be closed primarily but might require galeotomies.

- •

When closing scalp defects, layered closure is important to avoid wound dehiscence and excessive tension.

- •

Deep-layered closure should include a generous bite of galea.

- •

In the case of a large defect that cannot be closed primarily or with rotational flaps, if pericranium is intact, a skin graft can be used in non–hair-bearing scalp.

- •

Local pericranial, galeal, or temporoparietal fascia flaps can be used to provide a vascularized surface for a skin graft.

- •

Tissue expansion should not be the initial intervention in an open scalp wound but can be used secondarily for better cosmesis.

- •

Forehead repair can usually be accomplished primarily or with local flaps.

- •

If the defect is too large, a skin graft can be a temporary patch for tissue expansion but often gives unsatisfactory long-term cosmetic when used alone.

Ear

- •

Aside from a partial or complete avulsion, the ear can usually be repaired bedside.

- •

Layered closure

- ○

Cartilage should be approximated with a clear 4:0 PDS.

- ○

Anterior or visible lacerations should be closed with 5:0 prolene or nylon.

- ○

Posterior or hidden lacerations can be closed with absorbable suture.

- ○

- •

All cartilage should be covered.

- •

If perichondrium is exposed with skin loss, consider postauricular skin grafting from the other ear.

- •

Small avulsions can be reattached; total avulsions should be microsurgically repaired using superficial temporal artery or postauricular artery.

- ○

The cartilage banking technique should be avoided and is often unsuccessful.

- ○

- •

Although most surgeons use fluoroquinolone antibiotics for cartilage exposure to cover for pseudomonas, this practice is anecdotal and not supported by data.

- •

Bolstering with dental rolls or mattress suturing should be performed to avoid hematoma or fluid accumulation.

- •

Permanent sutures and bolsters can be removed in 5 to 7 days.

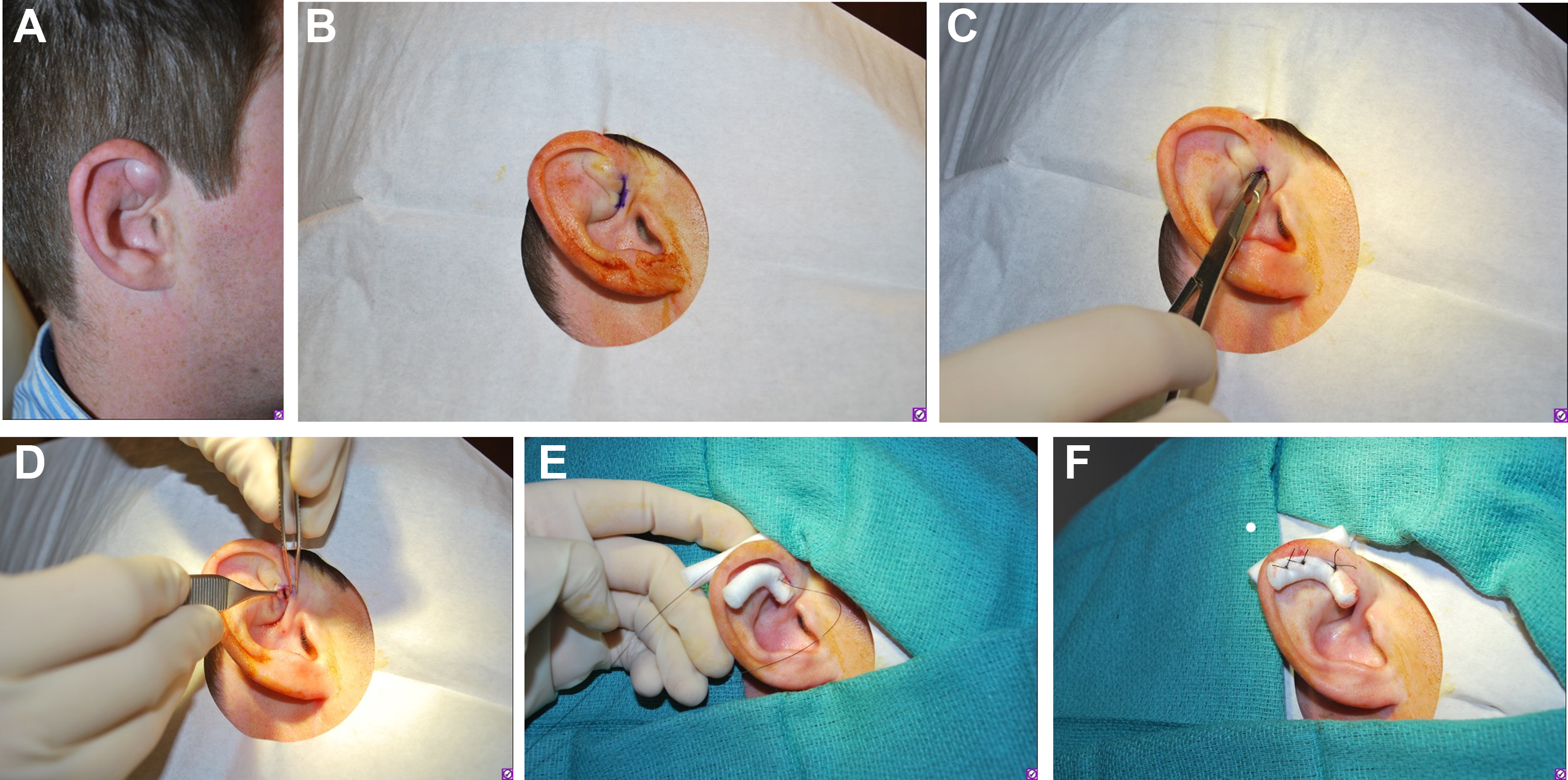

Special Consideration: Auricular Hematoma Management

- •

Shearing forces between the perichondrium and skin can cause auricular hematomas.

- •

These should be drained with sterile technique to avoid cauliflower ear.

- •

If the hematoma or fluid collection is greater than 48 hours old or recurrent, these authors have found that scraping the area with sterile gauze after drainage can help prevent reoccurrence.

- •

Auricular hematomas most often occur in young men in combat sports.

- •

Both an otolaryngology consult and a bolster dressing application have been found to prevent recurrence ( Fig. 2 ).