Crooked or deviated noses pose a specific challenge as many of the elements in a deviated nose are not symmetric and therefore not ideal for preservation techniques. Deviated noses are often where a hybridization between preservation and structural rhinoplasty is required. Careful preoperative evaluation of the soft tissue and bony anatomy of the patient is very important and congenital or post-traumatic asymmetry may involve more than the nasal pyramid. Full exposure of the nasal pyramid allows for visualization and appropriate osteotomy or rhinosculpture.

Key points

- •

Crooked noses are among the most difficult cases in rhinoplasty.

- •

A partially structural approach may be required while adhering to preservation techniques.

- •

Careful examination of facial bony asymmetry is paramount.

Introduction

The principles of preservation rhinoplasty are to respect conserve or restore the soft tissue envelope ligaments, minimize the resection of cartilage through reorientation and to keep the dorsal continuity of the patient’s own bridge. The origins of the operation date back to the beginning of the 20th century. Although initially described as an endonasal procedure, preservation rhinoplasty can be performed via open or closed approaches.

Crooked or deviated noses pose a specific challenge, as many of the elements in a deviated nose are not symmetric and therefore not ideal for preservation techniques. Indeed, deviated noses are often where there is a hybridization between preservation and structural rhinoplasty.

The first question to ask is whether the deviation is part of a facial asymmetry—that is, the underlying foundation of the nose (maxilla) is different between left and right sides either in left to right vertical height or anterior posterior discrepancy. This is usually obvious by looking at the orbit or brow position, the insertion of the alar base of the cheek, the cant of the smile, and the dentition if the patient has not undergone orthodontic treatment. It is easy to assess bony asymmetries by using a head down frontal photograph or by walking round behind the patient to examine the nose from above. This ascertains whether the deviation involves predominantly the bony pyramid, the cartilaginous part of the nose, or the whole nasal structure. It also permits assessment of asymmetries in the nasal sidewalls and the tip. The axis of a nose can be straight but sidewall asymmetry can create the appearance of deviation. ,

Trauma in childhood often results in a similar growth-related disorder to the developmentally deviated nose without a history of injury, except here there will be evidence of the previous injury with angulations in the cartilaginous and bony dorsum. The septum has a major role to play in deviated or crooked noses particularly as it may contribute to a dysfunctional airway due to compromise of the nasal valve—anywhere from the front of the nostril to behind the head of the inferior turbinate. The secondary changes in the turbinate size or shape usually demand that lateral nasal wall surgery will be combined with rhinoplasty or endoscopic sinus surgery.

This makes an external and internal and functional assessment so important in deciding the appropriate procedure. Careful palpation of the nasal pyramid and CT scanning is highly recommended in evaluating the underlying architecture nose and septum plus examination of the nose by endoscopy ( Fig. 1 ).

Crooked or deviated noses

The working definition for deviation can be any deviation of the nasal form from a vertical line dropped from the midpoint of the intercanthal distance. This of course is an approximation as in facial asymmetry the midline between the eyes, the philtrum the dental midlines and the chin point may not lie on the same vertical axis. However, we assume that the nose is the central feature about which we evaluate the whole face; however, this seems to vary between Western and Asian cultures. For facial learning and recognition, westerners focus more on the eyes and mouth in a triangular pattern, whereas Eastern Asians rely more on the central face, mainly the nose. So the perception of facial deformity and tolerance of deformity particularly with respect to the nose may differ between different cultures.

In Western noses which in general are slimmer with a higher dorsum and have more projection, deviation of the nose creates very different profiles particularly in the three-quarter view often leading to the adoption of ‘head tilt’—an adaptive mechanism whereby an individual often subconsciously presents the perceived least deformed side in pictures or face-to-face meetings.

These variations in perception may need to be accounted for in a patient’s acceptance of improvement over perfection—something that is very difficult to achieve in deviated noses, that is, an improvement is possible, symmetry is not, especially from all the different angles. A straighter nose is possible on an asymmetric face.

In the history of preservation rhinoplasty, one of the reasons dorsal preservation may not have been adopted for deviated or crooked noses was the inability to correct a deformed or twisted bridge and for the need to correct a complex septal deformity. There may be several reasons why preservation techniques are now being reapplied to deviated noses. The first is the ability to accurately image by CT or cone-beam CT, the second is the ability to reshape and move nasal bones using the piezoelectric technology, and the third is a reappraisal of the management of the nasal septum in deviated noses, moving away finally from the ‘L strut’. Fundamentally therefore, the ability to change the foundation of the nose (maxilla) or the roof (dorsal profile) safely and predictably means the preservation techniques can be applied to noses other than those that have existing pleasing dorsal aesthetic lines.

The basis of a straight nose is to have a central septum fixed to a midline nasal spine and equal sidewall slopes in terms of angulation, if not length. Creating more symmetric dorsal aesthetic lines but perhaps not symmetric lateral aesthetic lines is probably a realistic goal in correcting nasal deviations by preservation. Additional augmentation of one side of the maxilla is possible with diced cartilage or fat transfer.

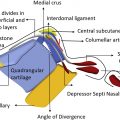

The skin envelope

Developmentally deviated noses invariably have differences in the size of the soft tissue envelope—not only skin but also the muscles and ligaments. The soft tissue envelope has an ability to adapt or contract there is often considerable difference in the healing response from a deception in the subperichondrial/periosteal plane compared with the sub-SMAS. Although it may be possible to preserve many of the ligaments in deviated noses, some may have to be modified. In particular, the position of insertion of the vertical scroll ligament on the short side of the deviated nose will be different with the repositioned nasal pyramid. Release of certain ligaments, for example, the pyriform ligament and adjacent upper lateral/nasal junction may be necessary to create length on the short side of the nose. When an overprojected deviated nose is reduced, however, there will be a relative excess of the envelope. If there is little need to adjust the profile, a straight nose that has axis deviation to one side may not need a soft tissue dissection over the upper laterals or nasal bones and shifting the pyramid to one side can readily correct minor axis deviations ( Fig. 2 ).