Abstract

Pathologic changes of the oral mucous membranes involve the full gamut of systemic diseases ranging from genetic and autoimmune disorders, infections and neoplastic diseases, and the complications of our treatments for them. A thorough examination of the oral cavity, including palpation, is necessary to detect the sometimes subtle signs of systemic disease as well as more localized problems of the soft tissues.

Keywords

Behçet’s disease, Candidiasis, Chelitis granulomatosa, Crohn’s disease, Graft-versus-host reaction, Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Lupus erythematosus, Multiple hamartoma and neoplasia, Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, Scleroderma, Sjӧgren’s syndrome

- •

A thorough examination of the intraoral soft tissues, including palpation, is necessary to detect the subtle signs of systemic disease as well as localized problems such as leukoplakia.

- •

Autosomal dominant cancer syndromes may present with diverse mucous membrane manifestations: odontogenic keratocysts in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome; papillomatosis in multiple hamartoma and neoplasia syndrome; pigmented macules in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

- •

The mat-like telangiectases of the lips and tongue are morphologically identical in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome and CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome (limited scleroderma).

- •

The most common causes of oral hyperpigmentation are ethnic pigmentation, cigarette-smoking, ingestion of drugs, heavy metals, antimalarials, and minocycline.

- •

Immunocompromised patients, especially those with very low CD4 counts, are at particularly high risk for oral pathology including necrotic ulcerative gingivitis, periodontitis, and osteitis, as well as oral hairy leukoplakia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

- •

The oral lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus and graft-versus-host disease mimic those of lichen planus; differentiation may require knowledge of the clinical situation and biopsy confirmation.

- •

Gingival hyperplasia is induced by antiseizure drugs, calcium-channel-blocking agents, and cyclosporine. Treatment consists of meticulous personal and professional oral hygiene or stopping the medication.

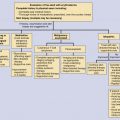

Pathologic changes in the oral mucous membranes can be involved in the full spectrum of systemic diseases, ranging from developmental disturbances and autoimmune diseases to infectious and neoplastic disorders ( Table 45-1; Figs 45-1 to 45-7 ). A methodic inspection of the soft tissues of the oral cavity with palpation of the gutters, floor of the mouth, tongue, and major salivary glands is necessary to complete a thorough physical examination. Clues to the presenting diagnosis or significant incidental findings, such as leukoplakia or oral carcinoma, may be disclosed. In this chapter, selected oral diseases with systemic implications are discussed and illustrated. The reader is referred to specific chapters for dermatologic diseases with oral mucosal manifestations (e.g., Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, lupus erythematosus, etc.).

| Category | Disease | Oral Manifestations | Cutaneous Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic | Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome | Odontogenic keratocysts | Palmar pits, multiple basal cell carcinomas |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome) | Mat-like telangiectases on the vermilion, tongue, buccal mucosa, and palate | Mat-like telangiectasia on the perioral skin and hands, particularly the fingertips | |

| Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease) | Papillomatosis ( Fig. 45-1 ) of the gingivae, dorsal tongue, and buccal mucosa | Facial trichilemmomas, acral keratoses, and occasionally palmar or plantar pits | |

| Inflammatory | Behçet’s disease | Aphthae—recurrent and severe ( Fig. 45-2 ) | Genital aphthae, pustular “vasculitis,” pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions, erythema nodosum-like lesions, pathergy is common |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Oral aphthae, pyostomatitis vegetans, cobblestone appearance of mucosa ( Fig. 45-3 ), linear ulcers, orofacial granulomatosis | Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum | |

| Lupus erythematosus | Leukoplakic patches, discoid lupus erythematosus lesions ( Fig. 45-4 ), aphthae | Photosensitivity, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, acute “butterfly” rash, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, leukocytoclastic vasculitis | |

| Scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis) | Reduced oral aperture, mat-like telangiectasia ( Fig. 45-5 ) (particularly in patients with CREST [calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia] syndrome), xerostomia | Acral or proximal sclerosis, calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, mat-like telangiectasia, murine facies, hypo- and/or hyperpigmentation | |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | Gingival hyperplasia with petechiae (strawberry gingivitis), oral ulcerations, poorly healing extraction sites | Palpable purpura, cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis | |

| Sarcoidosis | Infiltrative lesions, orofacial granulomatosis | Papules, nodules, granulomatous lesions in scars | |

| Infectious | Candidiasis | Thrush, angular cheilitis ( Fig. 45-6 ), median rhomboid glossitis | — |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia | Corrugated white plaques most commonly on the lateral tongue | — | |

| Neoplastic | Kaposi’s sarcoma | Blue to violaceous macular to nodular lesions | Lesions similar to oral cavity |

| Leukemia/lymphoma | Infiltrative lesions, boggy, friable gingival surface, erythematous to violaceous nodules of the lateral hard palate (ulceration common) | — | |

| Miscellaneous | Graft-versus-host disease | Reticular lichen planus-like lesions, lichenoid plaques ( Fig. 45-7 ), salivary gland dysfunction, thrush, mucositis, xerostomia | Lichenoid lesions or scleroderma-like changes |

Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome (OMIM #109400)

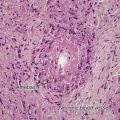

The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) is caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene on chromosome 9q22, PTCH2 gene on 1p32, or the SUFU gene on 10q24-q25. The autosomal dominant trait has high penetrance and variable expressivity. There is also a high spontaneous mutation rate (about 40% of cases). The major features of NBCCS are numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) at an early age, skeletal anomalies, palmar and plantar pits, and multiple jaw cysts. The jaw cysts, found in about 75% of affected persons, are odontogenic keratocysts (OKCs) that arise from dental lamina remnants or from basal cell components of overlying oral epithelium. They usually occur in the posterior portion of the mandible. An OKC may be the first sign of NBCCS in a child, and if there is more than one, a search for the other stigmata of this syndrome is indicated. The OKC is benign, but its growth may produce lateral bone expansion, displacement of teeth, and pathologic fractures. The histologic findings of OKCs are specific. The cyst cavity is filled with keratin. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, but there is a high recurrence rate. If one or more major criteria for the diagnosis of NBCCS besides multiple OKCs can be identified, genetic counseling and an aggressive program of skin cancer prevention with vigilant follow-up should be initiated. A novel oral hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib may be a beneficial adjuvant for adult patients who develop numerous or advanced BCCs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree