Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer

Victor J. Marks MD

Nathan W. Hanson MD

Background and Epidemiology

The term “non-melanoma skin cancer” (NMSC) refers to the types of skin cancers that are not melanomas and are grouped together because they tend to present and behave differently than melanomas. Generally speaking, this term also refers to two very common skin malignancies, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which are derived from keratinocytes, the cells that make up the epidermal layer of the skin. BCC is the most common malignancy in mankind, representing about 7 out of 10 diagnosed skin cancers. SCC, the second most common skin malignancy, represents about 2 out of 10 newly diagnosed skin cancers. It is estimated that over 1 million new cases of non-melanoma cancer will be diagnosed in 2008 and that one in five or six Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime. Of particular concern is the alarming increase in NMSC cases in young adults, with a very significant increase in the age group from 20 to 40 years. Other rare skin cancers, such as Merkel cell carcinoma, adnexal tumors, some sarcomas, and others, fall into the heading of non-melanoma skin cancers, but will not be individually addressed in this chapter.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

BCC generally presents quite innocuously as a red papule or small crusted area that tends to bleed and not heal. Most BCCs occur on sun-exposed areas, most commonly on the head and neck, but they may develop on any skin surface, including the extremities, trunk (particularly superficial BCC), genitalia, perineum, and around surgically created stomas. Often, they are mistaken by the patient for a nonhealing acneiform papule or other benign entity, and they may develop a crusted appearance due to the friable and easily traumatized tissue associated with BCCs. Given their slow growth, it may be months before a patient seeks attention for the area of concern.

SAUER’S NOTES

1. Sun protection measures are the mainstay of prevention.

2. Early and sometimes repeated skin biopsies are the mainstay of diagnosis. If it is worth removing, then it is worth a biopsy.

3. Follow-up visits are the mainstay of adequate discovery and therapy for recurrences.

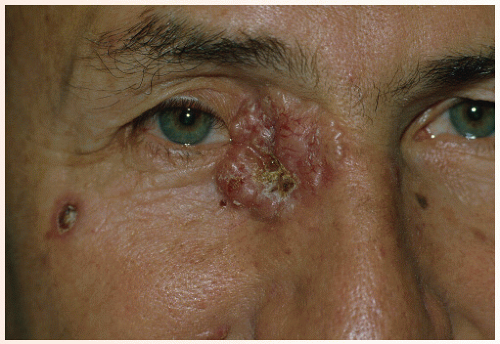

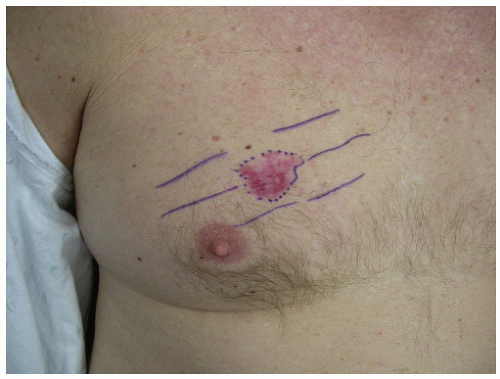

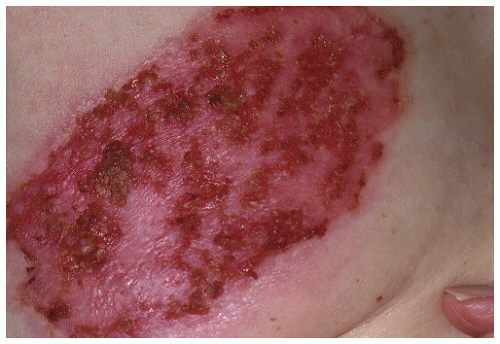

Clinically and histologically, there are many different variants of BCC that range from fairly slow growing and well-circumscribed nodular BCCs and superficial BCCs to relatively aggressive and clinically ill-defined variants known as morphea-form or sclerosing BCC. Other aggressive variants include infiltrative and micronodular BCC, which are mostly recognized by their histologic appearance. Nodular BCCs have a shiny, pearly appearance, and sometimes they have superficial blood vessels, called telangiectasias, running over their surface (Figs. 28-1,28-2,28-3,28-4). Some nodular BCCs are referred to as “rodent ulcers” due to the ragged central ulcer-like a rodent bite-within the nodule with smooth elevated borders. It is important to note that even small nodular BCCs often have a tiny central hemorrhagic crust. A sore that won’t heal or a bleeding point recurring at the same site should alert the physician to the possibility of an underlying BCC even in the absence of classic morphology. Superficial BCCs have scaly, red, sometimes shiny appearances that are commonly mistaken for plaques of eczema and psoriasis. They are eventually recognized as BCCs due to their lack of response to treatment (Figs. 28-5 and 28-6). Morphea-form or sclerosing subtypes have clinical similarity to scars or scar-like

plaques and have a tendency to grow rapidly and subtly and can, along with other aggressive subtypes, demonstrate perineural invasion histologically.

plaques and have a tendency to grow rapidly and subtly and can, along with other aggressive subtypes, demonstrate perineural invasion histologically.

FIGURE 28-3 ▪ Basal cell cancer at the nasolabial border with a central dell and translucent edge (often seen better with stretching of the skin) and telangiectasias. |

FIGURE 28-4 ▪ Nodular basal cell cancer with a translucent, telangiectatic, domed appearance. It mimics an intradermal nevus. |

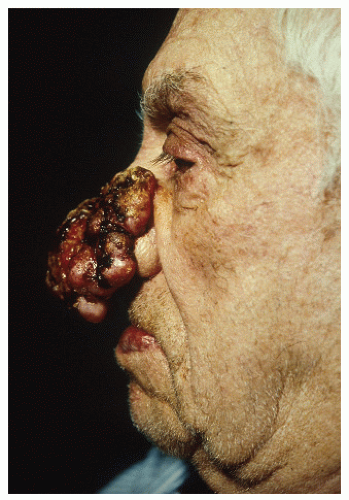

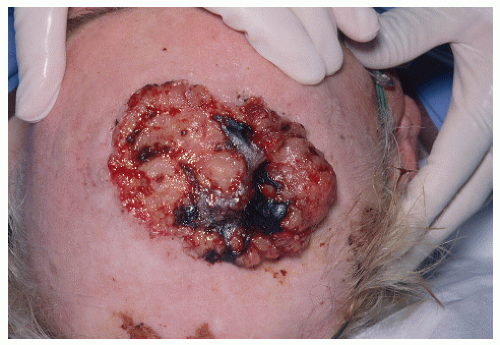

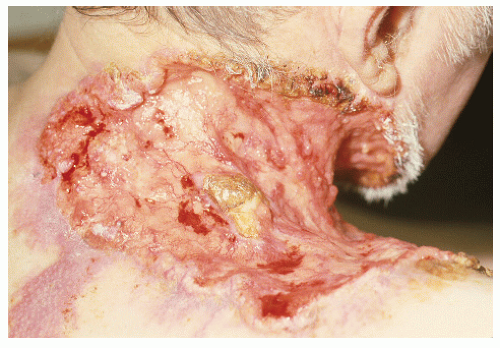

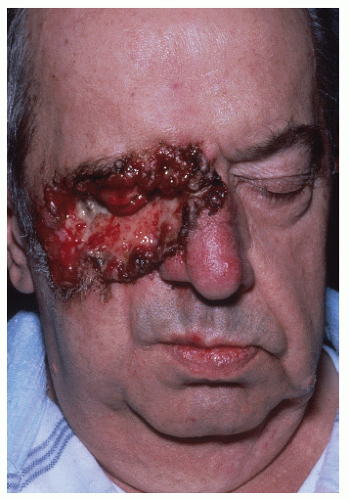

Although BCCs very rarely metastasize, and generally only in the setting of long-neglected tumors, they can be locally very destructive, invading neighboring skin, cartilage, bone, and other nearby structures (Figs. 28-7,28-8,28-9,28-10). The clinical differential diagnosis of BCC includes SCC, melanoma (especially when presented with pigmented variants of BCC or amelanotic melanomas), adnexal or follicular neoplasms, benign fibrous growths, scars, and other lesions.

Pathogenesis

Unequivocally, ultraviolet (UV) radiation plays a significant and primary role in inducing BCCs. Those at most risk for development of BCC are patients with a history of chronic sun exposure, light-colored eyes, fair skin that burns easily and tans poorly, and light-colored hair. Darkly pigmented individuals develop BCC much less commonly. The most common site of presentation of BCC is on the head and

neck, which are areas of the body that acquire the most exposure to UV light over an individual’s lifetime. However, as noted previously, BCC may occur on any skin surface, even those with minimal sun exposure.

neck, which are areas of the body that acquire the most exposure to UV light over an individual’s lifetime. However, as noted previously, BCC may occur on any skin surface, even those with minimal sun exposure.

FIGURE 28-9 ▪ A very large basal cell cancer. Even though metastasis of these tumors is very uncommon, the size of this tumor would necessitate a consideration of metastatic disease. |

FIGURE 28-10 ▪ Basal cell cancer with eye involvement. Radiation therapy might be considered as palliative or potentially curative therapy. |

Two genodermatoses further confirm the primary role of UV light in BCC pathogenesis. Patients with a rare autosomal recessive genetic skin disorder known as xeroderma pigmentosum exhibit exquisite sensitivity to UV light and are over 1,000 times more likely than the general population to develop BCC and other skin cancers. These patients lack the enzymatic ability to repair DNA damage that occurs as a direct result of UV light. Their risk is significantly decreased if they practice vigilant sun protection, beginning in infancy and continuing throughout their lifetimes. The other group of patients have the autosomal dominant condition nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. They have an allelic defect in a tumor suppressor gene, PTCH. They develop numerous BCCs in sun-exposed skin as their second, normal allele for the PTCH gene is damaged by UV light. Immunosuppression, regardless of the cause, seems to play a minor role in the development of BCC, but immunocompromised patients do carry a slightly increased risk for the development of BCC.

Other risk factors for the development of BCC include a history of x-ray exposure, either clinical or industrial, and other rare, inherited genetic disorders that predispose to the development of BCC specifically.

Treatment

Treatment for BCC depends a great deal on the histologic subtype, size, and location of the tumor. A variety of modalities have been described, including, but not limited

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree