Abstract

Neutrophilic dermatoses comprise a spectrum of skin diseases with various cutaneous manifestations and a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate on histopathology. Neutrophilic dermatoses are associated with a variety of systemic diseases including systemic vasculitis, inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancies, and many others. It is important for dermatologists to recognize cutaneous manifestations of neutrophilic dermatoses and understand work-up and management strategies for this spectrum of diseases.

Keywords

Behçet’s disease, Bowel-associated dermatosis–arthritis syndrome, Inflammatory bowel disease, Neutrophilic dermatoses, Pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome, Vasculitis

- •

Neutrophilic dermatoses encompass a spectrum of diseases marked by cutaneous lesions that on histopathologic examination show intense inflammation composed primarily of mature neutrophils.

- •

Behçet’s disease is a neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by an immune-mediated occlusive vasculitis of small, medium, and large blood vessels that is associated with a wide range of cutaneous and systemic findings.

- •

Sweet’s syndrome is typified by a cutaneous infiltrate of dermal or subcutaneous neutrophils often with fever that has been associated with a variety of underlying diseases and medications.

- •

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis marked by ulcerating skin lesions. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and other etiologies of cutaneous ulceration must be ruled out.

- •

Bowel bypass syndrome, later known as Bowel-associated dermatosis–arthritis syndrome, is a neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by typical skin lesions in the setting of bowel surgery or inflammatory bowel disease.

Behçet’s Disease

Clinical Manifestations

Behçet’s disease is a complex multisystem vasculitis first described by the Turkish dermatologist Hulusi Behçet in the late 1930s. It is characterized by recurrent oral and genital ulcers, as well as ocular, articular, vascular, intestinal, and nervous system manifestations. Although relatively common in the Middle East and Asia, it is uncommon in northern Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. Behçet’s occurs in both genders and is primarily a disease of young adults.

Because there is no pathognomonic laboratory test, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria ( Table 5-1 ). The oral aphthae experienced by these patients are like those seen in patients with simple aphthosis (i.e., canker sores). They are usually multiple, painful, and occur in crops ( Fig. 5-1 ). The genital aphthae are similar, except that they occur less frequently ( Figs 5-2 and 5-3 ). Pathergy—the development of cutaneous papulopustular lesions 24 hours after cutaneous trauma (e.g., by needle prick or intradermal injection)—is a characteristic feature seen in many patients with Behçet’s disease. Various skin manifestations including vesiculopustular lesions, palpable purpura, Sweet’s syndrome-like edematous papules and PG-like ulcerations may be seen. Deeper subcutaneous lesions that mimic erythema nodosum can also occur.

| Recurrent oral aphthosis (at least three times in 1 year) |

| AND |

At least two of the following:

|

Behçet’s disease is a multisystem disorder. Posterior uveitis (i.e., retinal vasculitis) is the most classic ocular lesion seen, though various other ocular findings can occur. The arthritis seen in patients with Behçet’s disease is nonerosive and inflammatory, and affects both large and small joints. Neurologic manifestations have a late onset in patients with Behçet’s disease and are remarkably variable in their presentation. A vasculitis of the vasa vasorum, with a propensity to affect large arteries and veins, can be a cause of death in patients with Behçet’s. Vessel thrombosis and aneurysms likely due to chronic endovascular damage are reported typically as a late manifestation of disease. The kidneys are relatively spared in Behçet’s patients compared to other systemic vasculitides.

Pathogenesis

Behçet’s disease is considered an autoinflammatory disorder typified by an immune-mediated occlusive vasculitis of small, medium, and large blood vessels affecting both the arterial and venous circulation. The etiology of Behçet’s disease remains unknown, but various studies have implicated genetic factors, environmental pollution, viral and bacterial agents, and immunologic factors. Behçet’s has been associated with certain human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) including HLA-B51. A genetic predisposition that triggers immunologic disease in response to viral or other infection is one theory of disease pathogenesis and studies have implicated various antigens including streptococcal antigens, Helicobacter pylori , herpes simplex virus, and parvovirus B19. Dysregulation of innate and adaptive immunity, including increased activation of neutrophils, has also been demonstrated in patients with Behçet’s.

Histopathology

Early mucocutaneous lesions typically show a neutrophilic vascular reaction or true leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology. Tissue from late or chronic mucocutaneous lesions shows a more lymphocyte-dominant infiltrate. Similar histopathologic findings of a lymphocytic “perivasculitis” are reported from autopsy specimens of internal organs in Behçet’s patients.

Treatment

Therapy for mucosal lesions includes topical viscous lidocaine, potent topical corticosteroids, or intralesional corticosteroid injections. Oral colchicine therapy may be associated with a reduced severity and frequency of aphthae. Oral thalidomide therapy is extremely effective for mucocutaneous involvement. Low-dose weekly methotrexate therapy may be beneficial in selected patients. Oral dapsone may be substituted or added.

Systemic corticosteroid therapy, alone or with azathioprine, is a mainstay of treatment for more severe ocular and systemic disease. Cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine may be considered for patients with resistant ocular or neurologic disease. There is also increasing evidence for the efficacy of biologics including infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, and rituximab, especially in patients with uveitis. In most case reports where biologics were initiated, the extraocular manifestations also improved, but tended to recur if the drug was withdrawn. Early reports suggest possible benefit with agents directed against interleukin-1 (IL-1) or interleukin-6, especially in severe or refractory disease.

Sweet’s Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

Clinical Manifestations

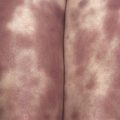

Sweet described a group of patients with one or more attacks of painful, erythematous plaques accompanied by fever, arthralgias, and leukocytosis. This syndrome is more frequent in women (female:male, 4:1) between the ages of 30 and 60 years. The characteristic lesion is a well-defined erythematous plaque often with a pseudovesicular, vesicular, or pustular surface ( Fig. 5-4 ). Lesions can occur at any location though they predominantly affect the face, trunk, and proximal extremities, and may develop at sites of trauma (pathergy). In some cases, lesions may present as deeper subcutaneous nodules with mild overlying erythema termed subcutaneous Sweet’s. Though ulceration is generally considered rare in classic Sweet’s, a new necrotizing variant with soft tissue necrosis has been reported. The lesions are accompanied by fever in most patients, and by myalgias and/or arthralgias in about half. Untreated lesions resolve over 6 to 8 weeks though recurrence may occur, especially in the setting of malignancy. Sites of extracutaneous organ involvement include bone (sterile osteomyelitis) and ocular (conjunctivitis, ulcerative keratitis) involvement as well as neutrophilic infiltration of the lungs, heart, nervous system, kidney, and gastrointestinal system.