This article outlines current methods in the evaluation and management of nasal fractures including clinical workup, imaging, and treatment.

Key points

- •

Nasal bone fractures comprise >50% of all facial fractures.

- •

Approximately half of all nasal bone fractures will have other associated facial fractures.

- •

CT is the gold standard imaging modality for nasal bone fractures.

- •

Nasal trauma workup must include evaluation for septal hematoma.

- •

Displaced nasal bone fractures should undergo closed reduction within 14 days of injury if possible.

Introduction

The nose is the gateway to our respiratory system and the cornerstone of the face, giving nasal injuries the potential to be both functionally and cosmetically impactful. The central location and natural projection of the nose away from the face makes it highly susceptible to injury from sports, assaults, and motor vehicle collisions; in fact, the nasal bones are the most frequently injured bones of the face. In this article we review the evaluation and management of nasal facial trauma, including fractures of the nasal bones, septum, and nasal cartilages.

Nasal anatomy

Externally the nose is composed of 2 paired nasal bones that form the superior bony wall of the nasal cavity, colloquially referred to the as the nasal bridge. The bones articulate with each other in the midline, superiorly with the frontal bone, posteriorly with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, and laterally with the frontal process of the maxilla. Inferior and caudal to the nasal bones lie the paired upper lateral cartilages, which are triangular and provide shape to most of the nasal dorsum. The nasal bones articulate with the upper lateral cartilages at an area referred to as the keystone. This junction provides stability and structure of the nasal dorsum. Continuing caudal along the nose, the upper lateral cartilages articulate with the paired lower lateral cartilages at the scroll region, which is one of the major mechanisms of nasal tip support. The lower lateral cartilages curl inferomedially to shape the nasal alae, which are flanked laterally by accessory cartilage and fibrofatty tissue.

The nasal septum is a combined bony and cartilaginous structure in the midline that divides the right and left nasal cavities. It is formed by the quadrangular cartilage, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, the vomer, the horizontal plate of the palatine bone, and the maxillary crest. The septum also houses a diverse vascular supply with several feeding vessels contributing to this region. Along the anterior septum, Kiesselbach plexus is a confluence of arteries from branches of the sphenopalatine and facial arteries. Posteriorly, Woodruff plexus provides blood flow from the sphenopalatine and posterior pharyngeal arteries. These highly vascularized regions provide collateral blood flow and may be a source of epistaxis following nasal trauma.

Trends in nasal bone fractures

Owing to its structure and location the nose is highly susceptible to injury, and nasal bone fractures comprise more than 50% of all facial fractures. , Common mechanisms of injury include assault and sports-related injuries, and less commonly motor vehicle collisions. Nasal fractures occur twice as often in men as in women with some postulating that this is due to a higher male predominance in contact sports and physical altercations. ,

Fracture patterns often arise based on the type of trauma. Anterior impacts result in damage to the nasal tip and cartilages, resulting in a flattened nasal dorsum and splayed nasal bones. Lateral impacts result in depressed displacement of nasal bones, C- or S-shaped nasal dorsum deformities, and medial maxillary wall fractures. Both anterior and lateral forces can lead to septal deformities. There are often associated fractures including the maxilla, orbit, and septum. As many as 67% of nasal bone fractures also have fractures of the frontal process of the maxilla, and as many as 42% have associated septal fractures ( Fig. 1 ).

Although classification systems for nasal bone fractures exist, none have been widely adopted by the facial trauma community. The Stranc-Robertson classification system was proposed in 1979 and stratifies injuries into three different planes based on frontal and lateral injury. , The Murray classification system from 1986 was developed by experimental injuries to cadaveric nasal bones and is based on pathologic findings and trends. The Modified Murray classification was proposed in 2007 and classifies nasal bone fractures in increasing severity based on displacement, laterality, and comminution. Despite these existing classification systems, clinicians instead often rely on descriptions of fractures based on examination and radiographic findings and terminology. Fractures are thus often described as unilateral or bilateral, displaced or nondisplaced, splayed, impacted, telescoped, or comminuted.

Evaluation and workup of nasal fractures

When working up nasal bone fractures, the initial step is to collect a thorough patient history including the nature of trauma and associated injuries, as well as evaluation for loss of consciousness, epistaxis, and perceived new-onset nasal obstruction. A thorough physical examination should be performed and any signs of epistaxis, bony step-offs, open fractures, and evidence of nasal obstruction should be noted. Examination should include anterior rhinoscopy and endonasal palpation to assess for obstruction, narrowing of the internal nasal valve, and septal hematoma. Bruising and tenderness may also serve as a clue to an underlying nasal bone fracture. Epistaxis should be managed in the acute setting, because inadequately addressed nasal bone fractures can lead to persistent epistaxis due to mucosal disruption overlying the fracture line. Nasal obstruction should be documented and followed clinically after management of the fractures. Note that swelling from the trauma may confound the evaluation and disguise or exacerbate evidence of nasal dorsal deviation or deformity. Photodocumentation is a helpful tool for assessing progression of swelling and deformity.

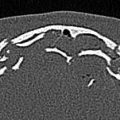

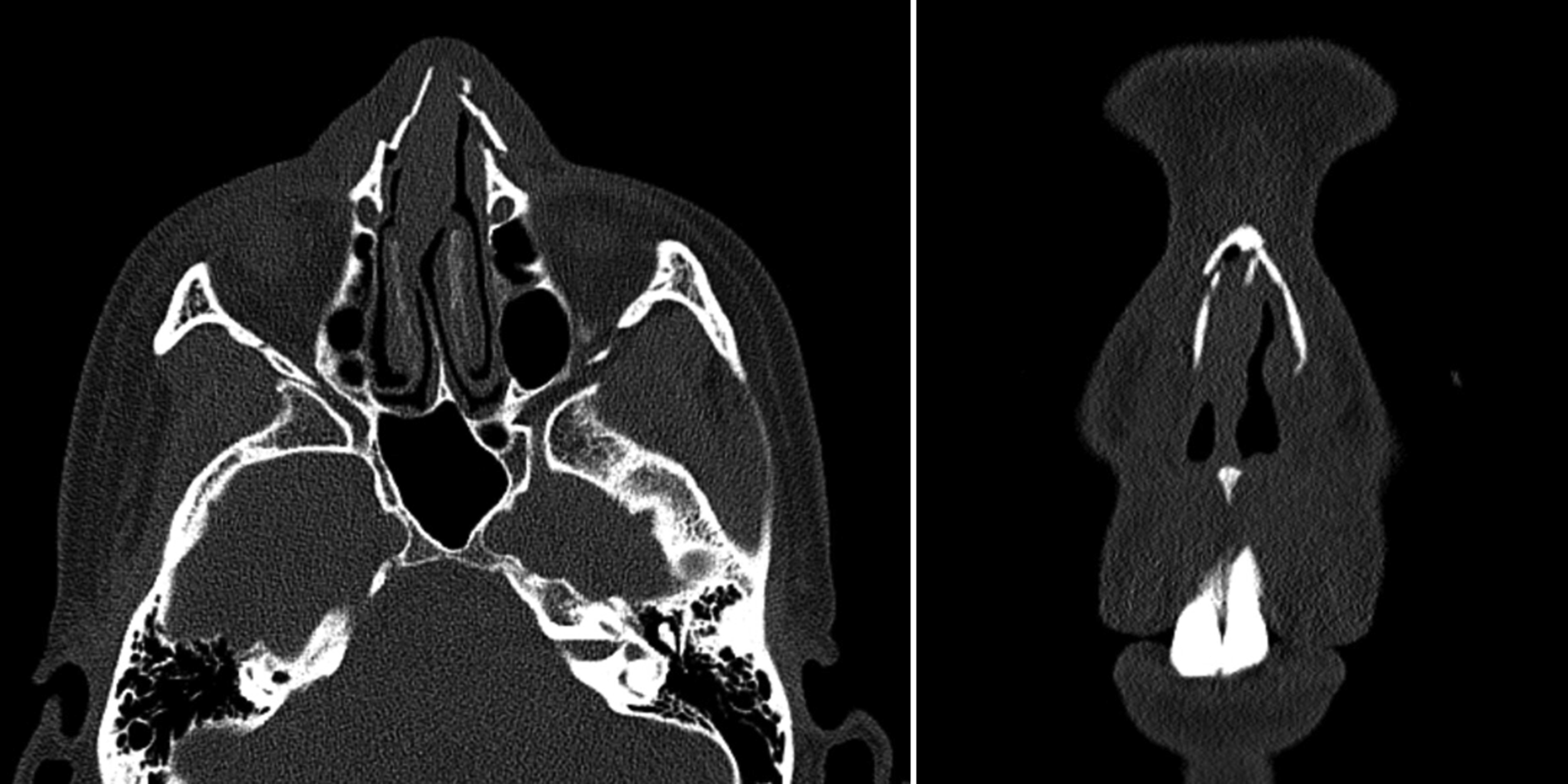

Although not necessarily indicated in isolated nasal bone fractures, imaging is often obtained following facial trauma to evaluate for concurrent maxillofacial bony injury. Depending on the mechanism of trauma, it may be indicated for medicolegal documentation. Lateral plain film radiographs are typically used in the acute care setting. These radiographs may definitively show nasal bone fractures but are limited in their ability to identify nondisplaced nasal bone fractures and septal injury. Noncontrasted computed tomography is much more commonly used in the emergency department setting and evaluates for nasal injury and other facial and head injuries. Although all planes should be evaluated, axial views are often the best way to evaluate for nasal bone fracture, as the axial plane best demonstrates nasal bone displacement, depression, splaying, impaction, and comminution ( Fig. 2 ). Imaging may be deferred in certain settings if there is strong clinical evidence of fracture and no concern for associated injuries, or if there is low suspicion for fracture due to no obvious deformity or nasal obstruction.

Complicated nasal fractures

When evaluating nasal bone fractures, one must also evaluate for other associated injuries and for complications including cosmetic and functional deformity. As previously mentioned, there may also be fractures of nearby structures such as the orbit, septum, and frontal process of the maxilla. Fractures of the pyriform aperture that are medially displaced must also be identified, because failure to reduce them may result in the medial buttress setting in such a way that causes significant nasal obstruction. Depending on the mechanism of injury, there may be more extensive facial or skull base fractures. If there are skull base fractures or injury to the cribriform plate, evaluation for cerebrospinal fluid leak and anosmia must be performed. Certain fracture patterns may also result in injury to the medial canthal ligament, leading to deformity and dysfunction of the eyelid and lacrimal duct.

Cartilaginous injury is rarer due to their flexible nature but may also be present in nasal trauma. This injury is often associated with injury of the high perpendicular plate, which affects the keystone and can cause disarticulation of the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal bones; this results in a depression of the middle third of the nose made more evident during inspiration. Nasal cartilage fracture or dislocation requires resuspension of the nasal cartilages to prevent persistent obstruction or dynamic collapse, and this often requires operative repair with or without cartilage grafting.

One of the most common complications of nasal bone fractures is injury to the nasal septum. This injury includes septal dislocation, fracture, or hematoma. Dislocation and fracture of the septum may require reduction depending on displacement and degree of functional deficit. It should be noted that concomitant septal fractures are associated with worse functional outcome after closed nasal bone reduction and is a risk factor for future open septorhinoplasty. Septal hematomas can lead to abscess formation or septal necrosis, which in turn can lead to septal perforation or a loss of the height of the nasal dorsum, known as a saddle nose deformity ( Fig. 3 ). Hematomas must be evacuated, and septal splints, nasal packing, or a quilting stitch should be placed as a bolster to prevent fluid from reaccumulating.