Minimally Invasive Aesthetic Surgical Procedures

Christopher J. Rizzi, MD

John J. Chi, MD, MPHS

Chapter Highlights

Although the popularity of minimally invasive aesthetics continues to rise, dramatic improvement in appearance at times requires a more invasive, surgical approach.

Blepharoplasty, facelift, and neck lift are surgical procedures that can offer more noticeable rejuvenation than noninvasive techniques.

Thread lifts are gaining in popularity and are an alternative to open surgical procedures to address the aging face and neck.

Facial rejuvenation can be achieved with nonsurgical, noninvasive modalities with astounding results; however, patients with more advanced signs of aging will see limited results from those interventions. For better or for worse, these patients require surgical intervention. It is important for the aesthetic facial surgeon to be competent in multiple surgical techniques to treat the aging face. Surgical treatment of the aging face can result in dramatic postoperative results, but also require more investment from the patient and the provider—time, effort, costs, and risks. Adoption of these surgical techniques into practice requires a thorough knowledge of the underlying anatomy and technical maneuvers specific to each modality of treatment. This chapter will succinctly discuss several important procedures for the aesthetic facial surgeon—blepharoplasty, facelift, neck rejuvenation, and thread lift.

The importance of addressing the periorbital region in the aging face cannot be understated. The eyelid and brow complex often show the earliest signs of aging, and the appearance of this region can distract from the benefits of other aesthetic interventions of the face.1 To this end, it is imperative for the aesthetic physician to be competent in the evaluation and treatment of the periorbital region. Blepharoplasty is an excellent method to address excess skin laxity and eyelid fullness and to redefine the eyelid crease. Both upper and lower lid blepharoplasty have the ability to create dramatic improvements in the appearance of the periorbital area and midface.1 The technique and anatomy of upper eyelid blepharoplasty are relatively straightforward with minimal variability. In contrast,

lower eyelid blepharoplasty anatomy, technique, and possible complications require a much more thorough understanding and experience. Only upper eyelid blepharoplasty will be discussed in this chapter. With the appropriate preoperative evaluation, attention to detail, and operative technique, dramatic results can be achieved with minimal risk.

lower eyelid blepharoplasty anatomy, technique, and possible complications require a much more thorough understanding and experience. Only upper eyelid blepharoplasty will be discussed in this chapter. With the appropriate preoperative evaluation, attention to detail, and operative technique, dramatic results can be achieved with minimal risk.

Preoperative Evaluation

In order to maximize aesthetic results and minimize postprocedural complications, a thorough preoperative evaluation of blepharoplasty candidates is imperative. Not only do these patients need to be assessed for candidacy for the surgical procedure, attention must be paid to the risk of potential complications related to the health of the eye. Patients at risk for postoperative dry eye, lagophthalmos, and ptosis can be identified preoperatively and counseled accordingly.2 It is also important to understand the eyes in the greater context of the brow-eyelid complex.3 Addressing redundant upper eyelid skin without addressing eyebrow ptosis can lead to unhappy patients and need for revision procedures. A ptotic eyebrow should always be corrected prior to the upper eyelid as correcting the brow ptosis will have an impact on the upper eyelid. Some providers elect to perform these procedures in the same setting, while others will perform a brow lift followed by a staged upper eyelid blepharoplasty.4

Candidates for upper eyelid surgery will commonly present with excess upper eyelid skin and upper lid fullness and complain about the appearance of fatigue. Thinning and redundancy of the upper eyelid skin commonly occur with age. Laxity of the orbital septum with fat herniation and hypertrophy of the orbicularis oculi muscle often leads to fullness of the upper lid. As with any other cosmetic procedure, it is important to understand the patient’s motivation for surgery in order to adequately address their specific concerns. An ophthalmologic history should also be taken, specifically regarding symptoms of dry eye, other ocular complaints, and prior procedures. If concerns arise, formal ophthalmologic evaluation will be necessary.

Physical Examination

The examination must not only concentrate on the underlying pathology, but also assess the patient’s risk for postoperative complication or poor aesthetic outcome. The periorbital region must also be evaluated in the greater context of facial rejuvenation. Upper eyelid dermatochalasis (excess upper eyelid skin) is present to a varying degree in the majority of older patients. This must be distinguished clinically from blepharochalasis. This is a recurrent inflammatory pathology of the eyelid resulting in recurrent edema and fullness of the upper lid. Blepharochalasis leads to stretching, thinning, and redundancy of the upper eyelid tissue through a different mechanism. Although patients with both of these pathologies can benefit from upper blepharoplasty, a thorough history and examination is necessary to distinguish between the two etiologies. During evaluation of the upper eyelid, the presence of excess upper eyelid skin, orbicularis hypertrophy, and pseudoherniated orbital fat should be assessed. With thinning of the orbital septum, pseudoherniation of the medial and central fat compartments commonly leads to upper lid fullness and must be addressed for the optimal outcome. The locations of upper eyelid fullness should be documented at the preoperative visit and any asymmetry noted.

To avoid postoperative complications, attention must be paid to the function of the eye. A general ophthalmologic examination is indicated, specifically if the patient has any complaints related to the eye.5 Unrecognized upper eyelid ptosis can lead to poor functional outcomes, need for revision surgery, and worsening of ptosis. Secondary signs of ptosis may include a hyperfunctioning frontalis muscle on the affected side. The patient should be asked to close the eyes and gently open without aggressively raising the eyebrow to reveal compensated ptosis. If ptosis is present, the patient should be referred to an oculoplastic surgeon

prior to performing upper lid blepharoplasty. Although this may result in loss of the patient referral, postblepharoplasty ptosis is a feared complication of upper blepharoplasty and can be difficult to correct.4 If there is clinical concern, dry eye and visual field testing may be indicated. The Schirmer test is commonly used to assess for dry eyes. The patient may also be referred for formal visual field testing prior to upper blepharoplasty if required. This is usually required prior to insurance approval for functional blepharoplasty.

prior to performing upper lid blepharoplasty. Although this may result in loss of the patient referral, postblepharoplasty ptosis is a feared complication of upper blepharoplasty and can be difficult to correct.4 If there is clinical concern, dry eye and visual field testing may be indicated. The Schirmer test is commonly used to assess for dry eyes. The patient may also be referred for formal visual field testing prior to upper blepharoplasty if required. This is usually required prior to insurance approval for functional blepharoplasty.

Appropriate photographic documentation is essential in the evaluation of all cosmetic surgery patients and blepharoplasty is no different. Preoperative and postoperative photographs should include the five standard views depicted in Figure 11.1. In addition, close-up frontal and lateral views of the eyes should be taken with the eyes in primary gaze, squinting, looking up, and closed.6

Anatomy

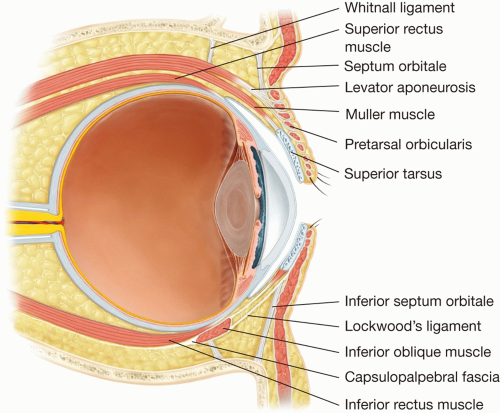

Thorough understanding of the anatomy of the upper eyelid is crucial to performing effective blepharoplasty. Adequate knowledge of the underlying anatomy is necessary both to

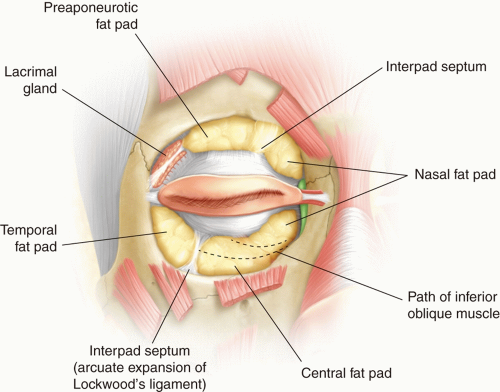

determine which patients would benefit from operative intervention and to formulate a comprehensive surgical plan. The anatomic layers of the eyelids are depicted in Figure 11.2. The layers of the upper eyelid vary dependent on the location relative to the tarsal plate. Generally, all blepharoplasty incision and dissection are performed superior to this important landmark. The layers of the upper lid in this region include the skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, levator aponeurosis, and Muller muscle. Above the levator aponeurosis, the orbital septum and orbital fat compartments lie deep to the orbicularis oculi. The supratarsal crease, usually 8 to 10 mm above the lid margin, is an important surface landmark in blepharoplasty. This crease is created by the insertion of fibers from the levator aponeurosis into the skin. This is minimally present in the Asian eyelid and is generally recreated for westernization of the upper eyelid. Deep to the orbital septum in the upper eyelid lie the medial (nasal) and central fat pads and laterally lies the lacrimal gland (Figure 11.3). Fat within the central compartment often drapes over the medial fat compartment and therefore superior retraction of the central fat will permit visualization of the medial fat pad. In addition, the medial fat is typically paler in color than the yellow central fat.

determine which patients would benefit from operative intervention and to formulate a comprehensive surgical plan. The anatomic layers of the eyelids are depicted in Figure 11.2. The layers of the upper eyelid vary dependent on the location relative to the tarsal plate. Generally, all blepharoplasty incision and dissection are performed superior to this important landmark. The layers of the upper lid in this region include the skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, levator aponeurosis, and Muller muscle. Above the levator aponeurosis, the orbital septum and orbital fat compartments lie deep to the orbicularis oculi. The supratarsal crease, usually 8 to 10 mm above the lid margin, is an important surface landmark in blepharoplasty. This crease is created by the insertion of fibers from the levator aponeurosis into the skin. This is minimally present in the Asian eyelid and is generally recreated for westernization of the upper eyelid. Deep to the orbital septum in the upper eyelid lie the medial (nasal) and central fat pads and laterally lies the lacrimal gland (Figure 11.3). Fat within the central compartment often drapes over the medial fat compartment and therefore superior retraction of the central fat will permit visualization of the medial fat pad. In addition, the medial fat is typically paler in color than the yellow central fat.

FIGURE 11.1 Standard photo array for a patient undergoing facial rejuvenation. (A) Right lateral, (B) right oblique, (C) frontal, (D) left oblique, and (E) left lateral views. |

Surgical Technique

Instrumentation

A general soft tissue instrumentation set with a #15 blade scalpel, curved tissue scissor, skin hook retractors, needle driver, and forceps will suffice for upper blepharoplasty. Many surgeons prefer to use the Westcott surgical scissors as these can provide more cutting accuracy and tactile feedback. A monopolar or bipolar electrocautery should also be available.

Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is typically sufficient for upper eyelid blepharoplasty although general anesthesia may be used depending on patient comfort or the need to perform concurrent procedures. Approximately 1 to 2 mL of lidocaine with epinephrine should be injected in the subcutaneous plane over both eyelids. If a corneal shield is utilized, topical tetracaine drops may be applied for patient comfort.

Incision Marking

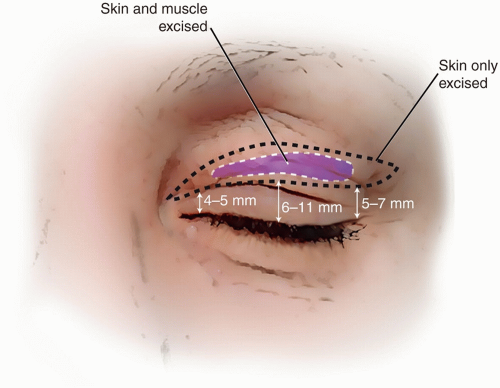

Appropriate marking of the skin to be excised is a crucial part of the blepharoplasty procedure. Inadequate resection of upper lid skin can lead to suboptimal cosmetic result or need for revision procedures. Overaggressive skin excision can lead to significant morbidity including lagophthalmos, scleral show, and keratitis.7 Marking should always be performed with the patient in the upright position and prior to the injection of a local anesthetic. The inferior incision should be placed at the level of the supratarsal crease, usually 8 to 10 mm above the lid margin at the mid-pupil. In Asian blepharoplasty, this incision is placed at the desired supratarsal crease. A pinch technique can then be performed to determine the amount of excess skin present. To do this, the excess skin is grasped with a smooth forceps and pulled to the point just prior to lid eversion. The superior incision and skin to be excised are then marked. This should be done at multiple points along the eyelid to determine the appropriate amount of skin excision. A general rule of thumb is that there should be 20 mm of skin present between the lid margin and the thicker eyebrow skin to avoid lagophthalmos. An elliptical skin excision is then marked utilizing the superior and inferior markings previously made. The incision should taper medially and not extend beyond the medial canthus to prevent

webbing in this region. Laterally, the incision may extend to the lateral orbital rim and may curve slightly upward into a skin crease if required for excision of standing cone deformity. The markings should be evaluated for symmetry. An example of appropriate skin marking is depicted in Figure 11.4.

webbing in this region. Laterally, the incision may extend to the lateral orbital rim and may curve slightly upward into a skin crease if required for excision of standing cone deformity. The markings should be evaluated for symmetry. An example of appropriate skin marking is depicted in Figure 11.4.

Procedure

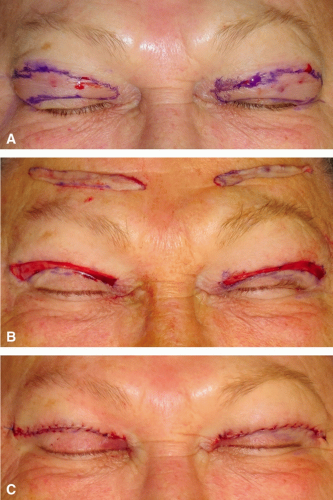

After appropriate skin marking has been confirmed, a local anesthetic is injected and the skin incisions are made. Incision is made through the skin only, preserving the underlying orbicularis. Resection of the orbicularis oculi may lead to orbital hollowing in some patients and consideration should always be given to preserving it. Starting laterally, the skin is dissected from the underlying orbicularis muscle and removed. At this point, a strip of orbicularis muscle may be removed within the middle of the skin excision if indicated to reduce upper eyelid fullness. Hemostasis is achieved with a cautery. If only skin excision is to be performed, closure is performed at this time (Figure 11.5).

If it has been determined that the patient requires fat excision, the orbital septum is identified and incised medially. This incision can be extended laterally over the central portion of the eyelid. The central fat is then readily identified and can be debulked, if indicated. Conservative removal of central fat will reduce the risk of postoperative A-frame deformity and hollowed upper eyelids.8 Gentle pressure may be applied to the globe to visualize redundant fat. Prior to removal of fat, a local anesthetic should be injected directly into the fat and an electrocautery is used for hemostasis. Retracting the central fat pad superiorly and laterally will reveal the pale colored medial fat. Again, gentle pressure is placed on the globe and the medial fat is cauterized and excised. Single layer closure is then typically performed with a 6-0 prolene suture in a running fashion. Care must be taken to perform a meticulous closure both medially and laterally to prevent medial webbing and standing cone deformity, respectively. To avoid lateral standing cone deformity,

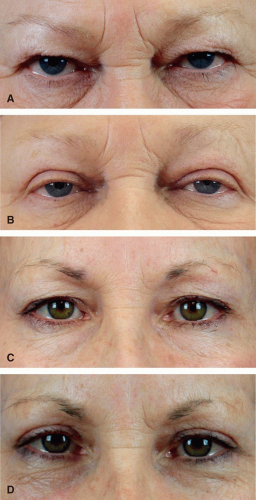

many surgeons close the lateral angle of the incision first—as the aesthetics of the central portion of the incision can accommodate mild to moderate skin redundancy. An ophthalmic antibiotic ointment is then applied to the incision. Pre- and postoperative photos are depicted in Figure 11.6.

many surgeons close the lateral angle of the incision first—as the aesthetics of the central portion of the incision can accommodate mild to moderate skin redundancy. An ophthalmic antibiotic ointment is then applied to the incision. Pre- and postoperative photos are depicted in Figure 11.6.

Postoperative Care

The patient may be discharged after the procedure. Cold compress application during the first 24 hours is essential to reduce swelling and ecchymosis. An ophthalmic antibiotic ointment should be applied to the incisions three to four times daily to reduce the risk of infection. Pain should be controlled with acetaminophen and a low dose narcotic may be required. NSAIDs should be avoided for 7 days postoperatively. Physical exercise should be avoided for at least 10 days. Prolene sutures should be removed in approximately 5 days. At the time of suture removal, close attention should be paid to the incision as partial dehiscence is not uncommon. A steri-strip may be placed over the lateral portion of the incision after suture removal to provide additional support for 24 to 48 hours after suture removal.

Complications

Most complications can be prevented by appropriate preoperative evaluation, surgical marking, and intraoperative hemostasis. Incisional erythema, sensation of tightness of the upper lid, tearing, and mild lagophthalmos are usually self-resolving. Hematoma is rare following upper lid blepharoplasty but may be heralded by increasing pain and swelling immediately postprocedure (Figure 11.7). Temporary lagophthalmos is not

uncommon after blepharoplasty and should be treated with lubricating eye drops and eye taping. Referral to an ophthalmologist may be required if the patient becomes increasingly symptomatic and persistent lagophthalmos may require secondary skin grafting.9 Blindness after upper lid blepharoplasty is rare and is generally secondary to unrecognized hematoma.10 Overaggressive fat resection, specifically in the central compartment, may lead to an A-frame hollowing within the central eyelid. This is a difficult problem to correct and may require revision surgery, fat or filler injection.

uncommon after blepharoplasty and should be treated with lubricating eye drops and eye taping. Referral to an ophthalmologist may be required if the patient becomes increasingly symptomatic and persistent lagophthalmos may require secondary skin grafting.9 Blindness after upper lid blepharoplasty is rare and is generally secondary to unrecognized hematoma.10 Overaggressive fat resection, specifically in the central compartment, may lead to an A-frame hollowing within the central eyelid. This is a difficult problem to correct and may require revision surgery, fat or filler injection.

Rejuvenation of the midface and lower face may be accomplished with both noninvasive techniques and surgical approaches. Since the first facelifts were performed in the early 1900s, our understanding of anatomy and surgical technique has evolved. Early techniques involved dissection and resuspension of the facial skin only. This limited approach led to an unnatural operated appearance and a rapid recurrence of facial ptosis. Lambros simply stated, “A young face is not an old face with tight cheek skin.”11 The major breakthrough in facelift understanding occurred in the 1970s when the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) was described by Mitz and Peyronie in 1976.12 Since this anatomic tissue structure was described, facelift techniques have concentrated on its dissection and suspension. With this evolution, contemporary facelift surgery is able to produce a natural appearing, long-lasting, dramatic result in appropriately selected patients. Many different techniques have been developed and further added to the mystique and confusion surrounding facelift surgery.13 It is important to realize that effective results can be achieved with multiple different facelift techniques and philosophies. For the developing aesthetic surgeon, the specific facelift technique performed is not as important as possessing a thorough understanding of anatomy, a strict attention to detail, and appropriate patient selection.

Patient Evaluation

As with all cosmetic surgery patients, it is important to understand and appropriately address the patient’s specific cosmetic concerns. Many patients requesting a facelift may be better suited for nonsurgical treatment with injectable fillers or neuromodulators. In

contrast, other patients may have significant signs of facial aging that requires a more aggressive open surgical approach to achieve a reasonable aesthetic result. It is important to understand the patient’s specific goals and risk tolerance. In contrast to many minimally invasive techniques, facelift patients can expect significant downtime and the risk of serious complications should be discussed.

contrast, other patients may have significant signs of facial aging that requires a more aggressive open surgical approach to achieve a reasonable aesthetic result. It is important to understand the patient’s specific goals and risk tolerance. In contrast to many minimally invasive techniques, facelift patients can expect significant downtime and the risk of serious complications should be discussed.

A thorough medical history should be taken for each patient including previous interventions, medical comorbidities that may put them at higher risk of complication, and any medications that could result in higher risk of bleeding. Patients with medical conditions, which may affect wound healing should be counseled as such, although surgery may still be performed. Smoking puts patients at high risk of healing issues and skin flap necrosis. Most surgeons will not perform facelift in currently smoking patients and will require that the patient abstain from all nicotine products in the perioperative period.14

Physical examination should involve evaluation of the patient’s general facial appearance and skin quality. Specific attention should be paid to the jowl and prejowl area, as this area can be dramatically improved with most facelift techniques. The neck should also be examined to determine whether the patient would benefit from concurrent submentoplasty or direct neck lift. The midfacial soft tissues are difficult to address with the facelift techniques described in this chapter and the patient should be counseled as such. Ideal facelift candidates have well-projected bony anatomy and adequate skin elasticity. Specifically, patients with prominent cheekbones and an appropriately projected chin are likely to see the best results. Those patients without adequate bony anatomy may be candidates for augmentation with silicone malar or chin implants. It is important to recognize these patients preoperatively, as outcomes from soft tissue repositioning alone can be suboptimal.

Anatomy

Understanding the tissue planes of the face is imperative to perform a safe and effective facelift. The layers of the face in the region of the parotid gland include the skin, subcutaneous fat, SMAS, parotid fascia, and parotid gland. Anterior to the parotid gland, the masseter muscle underlies the SMAS. Deep to the masseter lies the periosteum and bone. Traversing through these layers and attaching the periosteum directly to the skin are the facial retaining ligaments. These include the orbicularis, zygomatic, and mandibular retaining ligaments.15 Release of these ligaments in the sub-SMAS plane leads to an increase in the amount of lift achieved. These layers are depicted in Figure 11.8.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree