Leg Ulcers and Decubitus Ulcers

Gregory L. Wells

Jane Barry

An ulcer is defined as a wound with full epidermal involvement and some level of dermal loss. Partial-thickness wounds involve the epidermis and part of the dermis while full-thickness wounds extend through the dermis and may expose muscle, tendon, or bone. Chronic wounds are defined as those of over 6 weeks’ duration.

In the United States, it is estimated that 2.5 million people have leg ulcers with venous ulceration accounting for around 70% to 80%. Although venous disease, arterial disease, and neuropathy account for the majority of leg ulcers, there is a long list of possible diagnoses that should be considered including infection, neoplasia, medication, pyoderma gangrenosum, necrobiosis lipoidica, vasculitis, calciphylaxis, panniculitis, hypercoagulable states, and hematologic disorders. Other factors that should be taken into account for chronic ulcers are those that affect wound healing. These include age, nutritional status, continued pressure, shear and frictional forces, chronic illness, inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, immunosuppression, reduced oxygenation of tissues, bacterial load, stress, contact dermatitis, and noncompliance with treatment.

A detailed history and physical exam are essential to aid diagnosis of the etiology of the ulcer, to assess factors that affect healing and to form a comprehensive management plan for each patient (Table 20-1) (Appendix A). Furthermore, there should be regular assessments to monitor healing progress. Body drawings, wound tracings, and photography aid both assessment and documentation.

Approach to the Patient with an Ulcer

Measuring the Wound

For length, the longest distance is measured top to bottom regardless of orientation. Width is the longest distance side to side perpendicular to the length. To measure depth, a cotton-tipped swab is inserted into the deepest portion of the wound. The swab is grasped by its handle flush with the wound margins and is removed. The distance between the tip of the swab and the fingers is then measured. This technique may also be used to measure tunneling and undermining.

Describing the Wound

The percentages of red healthy granulation tissue, yellow fibrinous slough, and black necrotic tissue should be documented. Dead tissue serves as a medium for microorganism proliferation and may slow healing.

Table 20-1 Key Points in the Assessment of Leg Ulcers

HISTORY

PHYSICAL EXAM

Duration, onset, precipitating factors, and clinical course

Anatomic location

Associated symptoms: ulcer, neuropathy, vascular insufficiency

Size: length, width, depth, shape

Alleviating and exacerbating factors

Edge: punched out, sloping, indurated, presence of new epithelial tissue

Previous treatments and effects

Undermining/tunneling: depth and location

Pain assessment

Assessment of nutrition

Wound bed: granulation tissue, fibrin slough, necrotic tissue, black eschar (percentage involvement of each)

Previous treatments and effect

Exudate: amount and type, odor

Full past medical history: diabetes, atherosclerotic disease, lower limb surgery, trauma or radiation, previous ulceration (also see above)

Partial thickness (to dermis) versus full thickness. Presence of exposed tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone

Medications, including anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant, hydroxyurea, illegal drug use, all topical treatments

Surrounding skin: erythema, callosity, maceration, scarring, dermatitis, lower limb edema, signs of venous hypertension or arterial insufficiency

Family history of chronic wounds

Peripheral pulses, capillary refill time

Social history (e.g., occupation, smoking, alcohol use, impact on quality of life, home environment, travel history)

Neurologic exam

Cardiovascular exam

Abdominal exam

Drainage can be serous, serosanguineous, sanguineous, or purulent:

Is the dressing saturated or dry?

Is the wound oozing over the ulcer edge?

Investigation

The etiology of the ulcer can often be determined by clinical assessment alone. Additional tests, such as ultrasound, arterial and venous duplex, and ankle-brachial indices (ABI) are useful in selected cases. ABI is calculated by dividing the ankle systolic pressure by the higher of the two systolic pressures obtained from the brachial arteries in both arms. Normally the ankle pressure should be equal to the arm pressure. ABIs in diabetics or in those with calcified vessels can be falsely elevated. Laboratory investigations may also be indicated by assessment and include: complete blood count and differential, fasting glucose and lipids, serum albumin, ferritin and zinc, inflammatory markers, hypercoagulability screen, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, and hepatitis screen. Specimens for cultures should be obtained by biopsy or following wound debridement to aid differentiation between colonization and infection. When the diagnosis is still unclear or the ulcer is unresponsive to therapy, a biopsy and fungal and mycobacterial cultures should be considered to rule out other causes of chronic leg ulcers. Either multiple sampling biopsies or preferably a deep-wedge biopsy including the ulcer bed and edge are required for histopathology. Patch testing may be considered if a contact allergic component is suspected and plain film, blood cultures +/- more specific investigations if an underlying osteomyelitis is suspected.

Treatment

Treatment of leg ulcers is dependent on identifying and treating the cause and exacerbating factors and meticulous wound care (Appendix B). Management of leg ulcers can be difficult and requires significant dedication from the patient and the provider. Healing is evidenced by a decrease in ulcer dimensions, an increase in granulation tissue, and re-epithelialization. An approach to a chronic wound or skin ulceration is presented in Figure 20-1. Specific dressing types and examples are mentioned in Figure 20-1 as well as in more detail in Table 20-2.

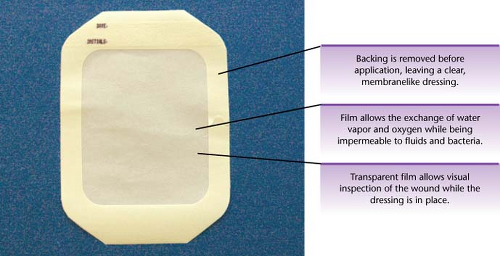

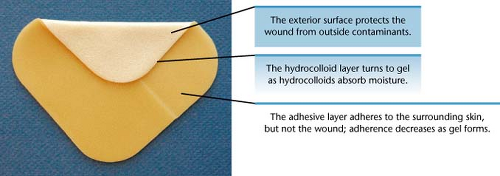

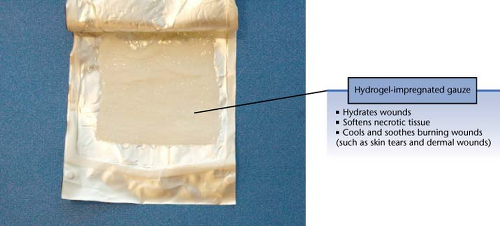

For most wounds, an occlusive dressing will maintain adequate moisture and may permit a patient to have a dressing on for more than 24 hours. The interval in dressing changes depends on the type and quality of the wound. There are five main types of dressing available (Table 20-2) (Figs. 20-2 to 20-6).

Good Wound Care

The basic principles of wound care include keeping the wound clean, keeping the wound moist, and keeping the tissue well nourished.

Clean Wound

Maintaining a clean wound is essential for the healing process. Depending on the wound, this can be accomplished by mild soap and water or with saline.

This should be performed on a regular basis to ensure that the wound continues to be clean. Depending on the patient and the location of the wound, patients may need assistance with this. If patients develop an infection, this will increase healing time for the wound and may lead to cellulitis, sepsis, osteomyelitis, or other complications. Usage of hydrogen peroxide solution, povidone iodine, or acetic acid solutions is contraindicated, as they are cytotoxic to migrating/dividing keratinocytes in the wound base.

This should be performed on a regular basis to ensure that the wound continues to be clean. Depending on the patient and the location of the wound, patients may need assistance with this. If patients develop an infection, this will increase healing time for the wound and may lead to cellulitis, sepsis, osteomyelitis, or other complications. Usage of hydrogen peroxide solution, povidone iodine, or acetic acid solutions is contraindicated, as they are cytotoxic to migrating/dividing keratinocytes in the wound base.

Figure 20-1 An approach to a skin wound/ulceration. Redrawn with permission from Baranoski S. Wound and skin care: Choosing a wound dressing, part 1. Nursing 2008;38(1):60–61. |

Figure 20-2 Transparent film dressings. Springhouse. Lippincott’s Visual Encyclopedia of Clinical Skills. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2009. |

Figure 20-3 Hydrocolloid dressings. Springhouse. Lippincott’s Visual Encyclopedia of Clinical Skills. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2009. |

Figure 20-4 Foam dressings. Springhouse. Lippincott’s Visual Encyclopedia of Clinical Skills. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2009. |

Figure 20-5 Hydrogel dressings. Springhouse. Lippincott’s Visual Encyclopedia of Clinical Skills. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2009. |

Table 20-2 Dressing Types | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Moist Wound

Wounds re-epithelialize more rapidly when the wound bed is kept moist (not wet) due to enhanced keratinocyte migration. Moist wounds can be maintained with topical ointments such as white petrolatum. Many patients will heal only

using white petrolatum. An antibacterial ointment is not necessary in most cases. Some patients may need topical antibiotics due to infection; however a few may become sensitized to these products or other preservatives in topical medicaments. This leads to an allergic contact dermatitis and complicates the healing process. Also, allergy to topical antibiotics such as neomycin or bacitracin may develop in chronic ulcer patients. In addition to topical ointments, dressings are essential to maintaining a moist wound.

using white petrolatum. An antibacterial ointment is not necessary in most cases. Some patients may need topical antibiotics due to infection; however a few may become sensitized to these products or other preservatives in topical medicaments. This leads to an allergic contact dermatitis and complicates the healing process. Also, allergy to topical antibiotics such as neomycin or bacitracin may develop in chronic ulcer patients. In addition to topical ointments, dressings are essential to maintaining a moist wound.

Tissue Nourishment

The first consideration in healing an ulcer is to assess the nutritional status of the patient. A malnourished and/or vitamin-deficient patient will heal more slowly. Assessing levels of vitamin A, C, E, and zinc as well as a prealbumin level are helpful. Keeping the tissue nourished is challenging for many ulcer patients. Essentially, this means increasing the oxygen available to the wound base through improved blood flow or by adding pressure on the leg to decrease edema and improve venous flow. For arterial ulcers, vascular bypass may be necessary to heal recalcitrant ulcerations.

Venous Leg Ulceration

|

An 71-year-old man presents with a 3-year history of a nonhealing ulcer located over the medial malleolus on his right ankle (Fig. 20-7). He gives a history of a right deep venous thrombosis 5 years previously. His right leg is edematous and the ulcer is large and irregularly shaped, measuring 4 cm × 6.5 cm. The wound bed is covered with fibrous slough and the surrounding skin is macerated. Granulation tissue is seen in 10% of the wound bed. Exudation is moderate in amount and serous. Hemosiderin deposition, atrophie blanche, and a venous flare are seen in the surrounding skin. The ankle brachial index is 0.9. What is the diagnosis? What treatment will be most beneficial to this patient?

Background/Epidemiology

Skin ulcerations caused by venous insufficiency are common in the general population and are the most commonly encountered leg ulceration. The overall prevalence of vascular ulcers is not known, but it is estimated at ∼1% of the population. Eighty percent of these ulcers are thought to be venous ulcers with the remaining 20% being arterial or mixed venous and arterial in nature.

Venous ulcers are associated with chronic venous insufficiency. Normally during exercise, leg muscle contraction increases venous return and decreases venous pressure in the legs. In patients with incompetent venous valves, venous pressure remains high despite exercise and muscle contraction. Though the pathophysiology of venous ulceration is not fully elucidated, it is known to be related to multiple predisposing factors, presented in Table 20-3. These elements may contribute to incompetence of the perforating and deep vein valves or calf muscle pump dysfunction. Venous hypertension results in inflammation leading to capillary damage, capillary leakage, and edema.

Key Features

Venous ulceration is often large, irregular in shape, and often located over the medial malleolus.

Signs of venous hypertension (edema/stasis dermatitis/varicosities) are common.

Compression of the lower leg and good wound care form the cornerstone of treatment.

Pathogenesis

With chronic venous hypertension, multiple cytokines and fibrinogen are released leading to more inflammation. In time, remodeling leads to capillary proliferation and a fibrous fibrinogen cuff in the vessel, impeding oxygen delivery. Alternately, some believe that ulcerations are caused by pressure-related vessel damage, leading to leaking of proteolytic enzymes and free radicals into the dermis. These processes lead to chronic inflammation resulting in stasis

dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, and eventually venous ulceration.

dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, and eventually venous ulceration.

Table 20-3 Risk Factors for Venous Ulceration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Presentation

Venous ulcers are located most commonly around the medial malleolus (the gaiter area) and vary considerably in size and shape (Fig. 20-7). They are often large and shallow. They may be single or multiple. The ulcer margin is well defined but not raised or undermined. The ulcer base may show yellow and doughy or healthy red hemorrhagic granulation tissue.

Other features to look out for in the surrounding skin:

Figure 20-7 Venous ulceration on the medial malleolus. From Nettina SM. The Lippincott Manual of Nursing Practice, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001. |

Stasis dermatitis is common and presents with scale, erythema, and itch

Signs of venous hypertension:

Pitting edema

Varicosities, which are tortuous, dilated veins. They may cause discomfort on prolonged standing and during pregnancy

Venous flares: dilated veins around the ankles

Extravasation of red blood cells leading to hemosiderin deposition and melanin deposition following inflammation lead to petechiae and brownish pigmentation of coalescing macules.

Atrophie blanche: a term describing ivory-white atrophic sclerotic plaques with a red stippling at the periphery. These are also found in certain hypercoagulable states.

Lipodermatosclerosis describes the condition when the subcutaneous tissue of the lower extremity becomes woody, indurated, sclerodermatous, and fibrotic. Early on it may be mistaken for cellulitis, later on it results in the appearance of an inverted champagne bottle with tapering distally at the ankle and proximal swelling.

If dermatitis is well demarcated or does not respond to traditional treatment a contact dermatitis may be present. This can be caused by components of topically applied medications (antibiotics, preservatives, anesthetics), dressings, or rubber in elastic stockings.

Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma: an exaggerated stasis dermatitis presenting as purple well-defined plaques

Look for signs of co-existing arterial disease (see next section).

Symptoms

Venous ulcers are often painless. There may be a sensation of heaviness or aching or swelling of the lower leg particularly after prolonged standing. A history of preceding minor injury or infection may be elucidated.

Diagnosis

Ankle brachial indices should be measured before compression therapy to assess for arterial disease. It should be noted that values are not reliable in diabetics. Compression is contraindicated if the value is less than 0.5 and a value less than 0.8 indicates arterial disease and caution should be used. A vascular surgery opinion should be sought in cases with decreased values. Venous duplex ultrasound allows visualization of the veins and flow through the valves. Patch tests should be performed if a component of contact dermatitis is suspected. The ulcer should be measured carefully (length, width, and depth). Consider photographing the ulceration at each visit to aid assessment of progress.

Treatment

The patient should be counseled regarding duration of treatment. Fifty percent heal in 6 months and most are healed at 1 year

General advice:

Rest is an important part of the treatment regimen. Antigravity measures include limiting prolonged standing. When seated, the feet should be raised above the level of the heart and the end of the bed may also be raised in the absence of breathing difficulties/orthopnea.

Exercise should be encouraged to maintain the calf muscle pump.

Weight reduction advice may be appropriate.

Compression therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Graduated sustained compression decreases pressure in the superficial venous system. The optimal pressure is 35 to 40 mm Hg at the ankle. This improves edema and the effect of the muscle pump. Non-elastic or elastic systems may be used. Non-elastic bandages require muscle activity in order to work and are thus not recommended in immobile patients. Options for compression include Unna boots (moist zinc impregnated nonelastic bandages); multilayer elastic bandaging (which maintain a constant pressure for 7 days); orthotic devices; and compression pumps.

Patients should wear compression stockings for the rest of their lives. These are put on before rising from bed in the morning and kept on until bedtime.

There are four classes of stocking depending on the pressure at the ankle:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree