Abstract

Leg ulcers are a frequent medical problem associated with considerable morbidity, increasing healthcare costs, and a decrease in the quality of life of patients. Approximately 70% of leg ulcers are attributed to venous insufficiency, 20% to mixed venous and arterial disease, and 6% to arterial disease. Atypical ulcerations should be suspected when a wound presents in an atypical presentation (location, clinical features, and symptoms), or if it does not respond to standard treatment (8 to 12 weeks). In this case an ulcer biopsy should be performed and tissue sent to histology, culture, and—if relevant—immunofluorescence. The pillar of treatment is a correct diagnosis, management of infection, appropriate wound dressings, and compression (if arterial insufficiency is ruled out). Adjunctive therapies are to be considered after failure of standard treatment. In cases of arterial ulcerations that can be corrected, revascularization is indicated.

Keywords

Arterial insufficiency, Atypical wounds, Biopsy, Compression, Debridement, Leg ulcers, Revascularization, Venous insufficiency, Wound dressings

- •

Venous leg ulcerations are the most common cause of leg ulcers, followed by mixed venous/arterial disease and arterial insufficiency. However, up to 10% of leg ulcers are due to atypical etiologies, infections, metabolic disorders, neoplasms, and inflammatory processes.

- •

Venous insufficiency or dysfunction is caused by outflow abnormalities or venous reflux, resulting in sustained ambulatory venous pressures or venous hypertension.

- •

Arterial insufficiency results from failure to deliver oxygen and nutrients to the tissue. Progressive atherosclerosis is the most common etiology.

- •

Screening for arterial insufficiency should be performed—if clinically relevant—with the measurement of ankle–brachial pressure index (ABI). If ABI is >0.7, compression can be applied safely.

- •

Biopsy of the ulcer needs to be considered when atypical etiology is suspected, or when treatment response is not adequate.

- •

Wound size and wound duration are the main factors associated with wound healing.

- •

Standard of care for venous ulcerations consists of debridement, management of infection, appropriate wound dressings, limb elevation, and compression. If this fails, diagnosis should be reassessed and/or adjunctive therapy should be considered, including autologous skin grafts and tissue-engineered products, among others.

- •

Standard of care for arterial ulcerations is revascularization if possible.

Wounds, in particular chronic wounds, represent a clinical challenge to healthcare providers and an unmet medical need for patients. In the United States alone, chronic wounds affect an estimated 7 million patients annually. Leg ulcers are wounds located in the area between the knee and ankle and that is the definition we will use in this chapter.

|

Prevalence and Economic Cost

Leg ulcerations are a common clinical problem with considerable morbidity, high cost to society, and often a dramatic negative impact on a patient’s quality of life.

Leg ulcerations have a point prevalence rate of 0.3 to 0.6% and a lifetime cumulative risk of 1.0 to 1.8%. Venous leg ulcerations (VLUs) are the most common cause of leg ulcers, constituting up to 80 to 90%. The average annual incidence rate of VLUs is 2.2% in Medicare-aged populations and 0.5% in younger privately insured patients.

VLUs are associated with increased healthcare costs. Recent data indicate that patients with VLUs utilize significantly more medical resources and have increased annual incremental medical costs compared with matched patients without VLUs. Additionally, working patients with VLUs missed more days from work, resulting in substantially higher work-loss costs.

Pathophysiology

Overview

Although the differential diagnosis of leg ulcerations is extensive, in the Western world they are most frequently caused by venous insufficiency, arterial insufficiency, or a combination of these ( Table 46-1 ). In one large cohort of patients with leg ulceration, 72% of lesions were attributed to venous insufficiency, 22% to mixed arterial and venous disease, and 6% to predominantly arterial disease.

Atypical wounds are those chronic wounds not secondary to these causes, but rather the result of, among others, infections, metabolic disorders, neoplasms, and inflammatory processes. It is estimated that up to 10% of chronic lower-extremity ulcers are due to these less frequent etiologies. Dermatologists have a particular responsibility to recognize the less common causes due to training in the diagnosis of these conditions.

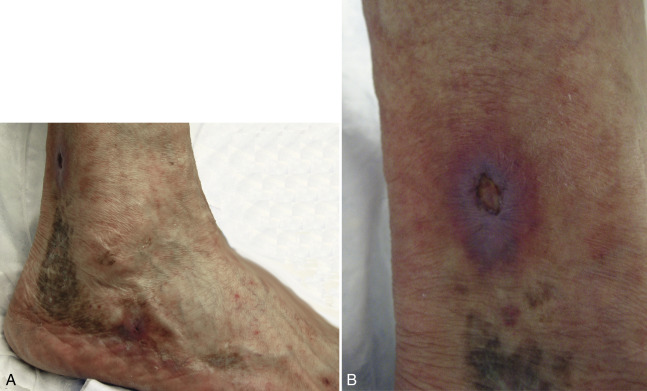

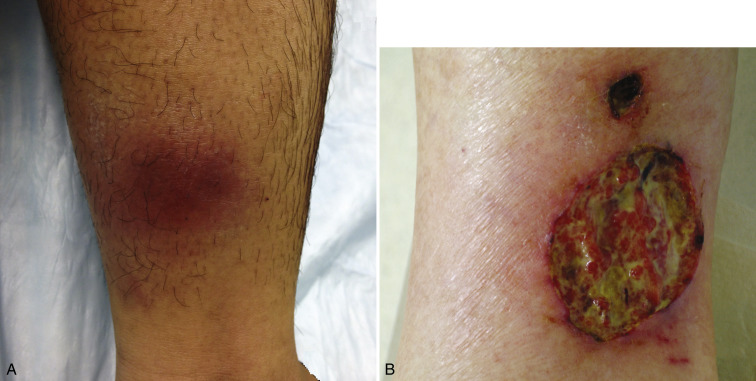

Appropriate therapy is critically dependent on an accurate diagnosis of the cause of the ulceration. For example, small-vessel disease associated with leg ulcerations may be difficult to recognize and may present as painful pinpoint ulcerations that heal with a white atrophic scar (livedoid vasculopathy; Fig. 46-1 ). Additionally, for example, care must be taken before establishing a diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum ( Fig. 46-2 ) because many other conditions can have similar presentations. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that ulcerations often have several contributing factors and different mechanisms of pathogenesis. A patient with pyoderma gangrenosum, for instance, can have arthritis and reduced ankle range of motion that might cause calf muscle pump dysfunction, which leads to venous insufficiency.

Pathophysiology of Chronic Ulcerations

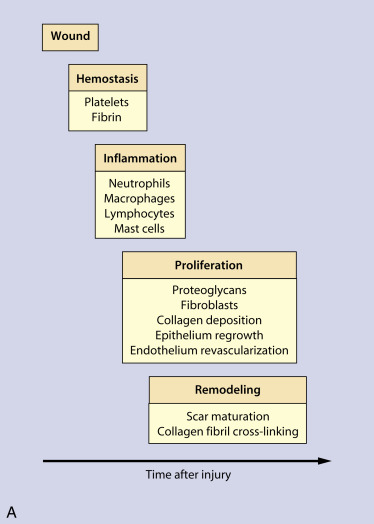

Normal wound healing is a dynamic, integrated process that requires the interplay of numerous factors. An acute wound heals in a series of sequential but overlapping phases known as hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling ( Fig. 46-3 ). A chronic wound fails to progress through this ordered healing process in a timely manner, but rather remains in a dysregulated, asynchronous, and prolonged inflammatory state, and, therefore, does not result in healing. Various factors that contribute to a nonhealing ulceration have been identified. Cells are affected and as an example fibroblasts appear oddly shaped and dysfunctional. Signals are perturbed, for example growth factors are deficient and metalloproteinases are often in excess and are associated with a state of ongoing destruction within the wound. Biofilms (communities of microorganisms in a polysaccharide matrix) can be present in a wound and form a structure that is difficult to penetrate with antibiotics, and they may affect healing. Increasing patient age, nutritional deficiency (especially protein and vitamin deficiency), chronic illness, chronic immunosuppression, hypoxia, vasculopathy, and infection all can contribute to poor wound healing.

We will briefly review the pathophysiology of the most common causes of leg, venous, and arterial ulcerations.

Pathophysiology of Venous Ulceration

|

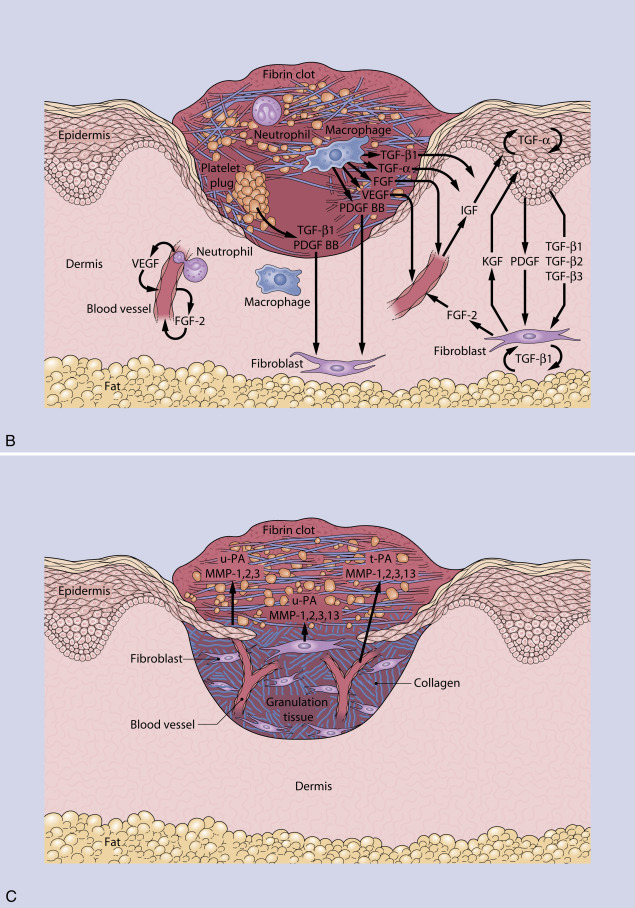

Venous blood flow in the lower extremities is dependent on the superficial, communicating, and deep venous systems. The long and short saphenous veins and their tributaries make up the superficial system. The communicating (or perforator) veins connect the superficial veins of the leg with the deep venous system. Communicating veins are equipped with one-way bicuspid valves that direct flow only into the deep system. The deep veins contain valves and are either intramuscular or intermuscular ( Figs. 46-4 and 46-5 ).

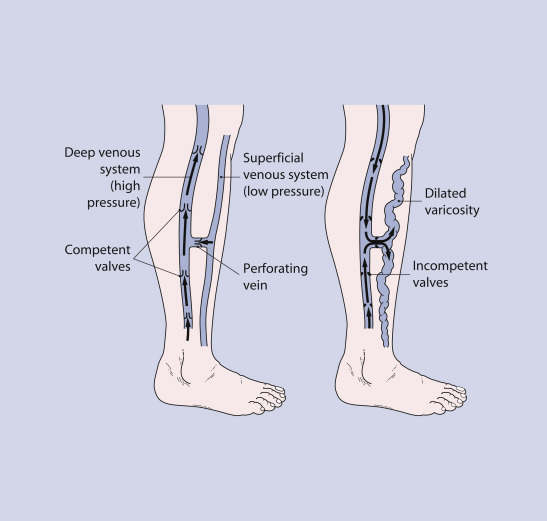

When a person is standing, the pressure in the superficial and deep venous systems is roughly equal to the hydrostatic pressure in the legs (80 mm Hg). During the muscle contraction phase of ambulation and with a full range of movement of the ankle, the calf muscle contraction exerts a pressure greater than 80 mm Hg in the deep veins, and blood is propelled cephalad. Proper valve function ensures unidirectional flow and prevents transmission of high venous pressure to the superficial drainage system. After deep venous emptying, calf muscle relaxation, and the muscle relaxation phase of ambulation, deep venous pressure decreases to 0 to 10 mm Hg. Valves open and allow flow from the superficial system to deep venous drainage. Generally, in a healthy person, veins empty and ambulatory venous pressure decreases during exercise; this process requires intact leg veins, intact venous valves, efficient calf muscle pumps, and no deep venous outflow obstruction ( Fig. 46-5 ).

In contrast, in persons with venous insufficiency or dysfunction outflow problems or reflux exist. This is associated with valve dysfunction, deep vein obstruction, and calf muscle failure, at times caused by decreased ankle range of motion. This results in increased sustained ambulatory venous pressure (also known as venous hypertension) during exercise, and it is most often due to obstruction or valvular dysfunction affecting superficial, perforator, or deep veins. As a result, patients develop edema and slow-healing wounds, most commonly on their lower legs, near their ankles.

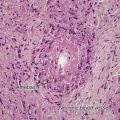

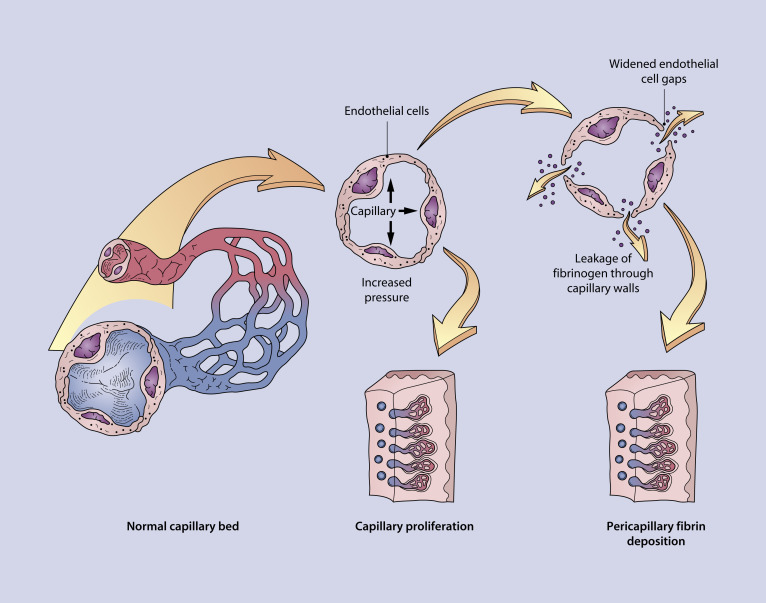

Although the causes of chronic venous hypertension (venous insufficiency) seem reasonably well understood, the pathophysiology of ulceration in venous insufficiency is still unknown. One theory postulates that increased intraluminal pressure in the capillaries causes leakage of fibrinogen through capillary walls with deposition of pericapillary fibrin cuffs and impairment of oxygen or nutrient diffusion to tissue; together, these changes may result in tissue necrosis and ulceration ( Fig. 46-6 ). A second theory regarding the mechanism of injury posits that the known sludging of white blood cells in venous insufficiency causes capillary obstruction. Trapped white blood cells may become activated and release proteolytic enzymes that promote ulceration. A third theory, the “trap” hypothesis, suggests that the leakage of fibrin and other macromolecules into the dermis traps or binds growth factors and reduces the amount available for tissue repair.

Pathophysiology of Arterial Ulceration

Arterial insufficiency results in local ulceration and skin, digital or even limb necrosis, depending on the severity of ischemia; the failure to deliver oxygen and nutrients to the leg results in tissue breakdown. Progressive atherosclerosis is the most common etiology, where the arteries become stenotic as a resultant of deposits of lipid and plaque deposition in arterial vessel walls. While some restrict the term to large vessel disease, any other process that obstructs the arterial flow can result in an arterial ulceration. Diseases associated with arterial insufficiency and formation of ischemic ulcers include large-vessel disease (thromboangiitis obliterans, arteriovenous malformations), small-vessel disease (Raynaud’s phenomenon), microthrombotic disease (antiphospholipid syndrome, cryoglobulinemia, and cholesterol emboli), vasculitis, sickle cell disease, and polycythemia vera, among others.

Patient History and Physical Examination Findings

|

History

An adequate history must be obtained to establish the cause of ulceration ( Table 46-2 ). A history of ulcerations may be predictive of future ulcerations. Medications, family history, social history, and review of systems also may provide important information. For example, a longstanding, nonhealing ulceration has less probability to heal, especially if older than 6 months. Atypical etiologies often suffer from delayed diagnosis including malignant etiologies ( Fig. 46-7 ). Contact allergy to topical medications used on the leg is a common aggravating factor (up to 65% of patients in some studies). A family history of ulcerations could be attributable to coagulopathy disorders; a social history of intravenous drug abuse may indicate that ulcerations could be caused by infection, or by injection of foreign material. On the other hand, past medical history of uncontrolled hypertension could be a clue to the diagnosis of Martorell ulcers ( Fig. 46-8 ), and a history of injections for cosmetic purposes may indicate a lipogranuloma. Patients may also have factitious or self-inflicted ulcerations ( Fig. 46-9 ).

| Venous (see Fig. 46-10 ) |

|

| Ischemic |

|

| Nonvascular |

|

| Infection |

|

| Osteomyelitis |

|

| Malignancy (see Fig. 46-7 ) |

|

| Metabolic |

|

| Hematologic |

|

| Medication (hydroxyurea) (see Fig. 46-18 ) |

|

| Multifactorial (any combination of causes) |

∗ Often caused by infection, medication, malignancy, and connective tissue disease.

Pain

Family history

|

Physical Examination

A focused physical examination could give us clues for diagnosis. For instance, paleness and jaundice in a patient could indicate the coexistence of sickle cell, and the absence of pedal pulses indicates arterial insufficiency. Key elements of the ulceration that can provide diagnostic information are outlined in Table 46-3 . The size of the ulcer should be documented at each visit with photographs and by noting dimensions of greatest length and perpendicular width and depth. Size and depth may be important prognostically because larger ulcerations are slower to heal. Any undermining, sinuses, or tunneling must be determined. The pattern of the ulcerations may also provide important clues. Characteristics of the ulcer base (color, presence of necrosis) can affect healing. The moisture level (dry, moist, or wet) and the presence or absence of exudate helps elucidate the cause of the ulceration and affect management decisions. The surrounding skin may suggest causes of ulceration (e.g., red, hot skin may indicate cellulitis).

| Location |

|

| Size |

|

| Pattern |

|

| Base |

Color

|

| Edges of ulceration |

| Sloping: characteristic of venous ulceration Vertical: characteristic of arterial ulceration Rolled: characteristic of basal cell carcinoma Undermined, violaceous: characteristic of pyoderma gangrenosum Stellate: livedoid vasculopathy |

| Surrounding skin |

Patterned

|

| Diminished pulse: large-vessel disease |

| Varicose veins: predispose patients to ulceration |

| Abnormal sensation and motor function: neurologic disease |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree