Hair Loss

Lilla Landeck

Nina Otberg

Overview of Hair Physiology and Anatomy

Hair Types

The human body exhibits three different types of hair: terminal, vellus, and lanugo hair. Fine hair on the fetal body is shed in utero or during the first weeks of life and is called lanugo hair. Terminal hairs are pigmented, thick, and visible, with a shaft diameter of greater than 60 μm, and are located over the scalp, armpits, pubic area, and in men, the androgen-dependent body areas (for example, beard, leg, and chest). In contrast, vellus hair is fine, soft, short, colorless, and has a shaft diameter of less than 30 μm. Except for the palms and soles, vellus hair can be found on the entire body although density varies considerably in different body sites.

Growth Cycle

Hair growth occurs cyclically, alternating periods of growth (anagen phase, 85% of hair follicles) with rest (telogen phase, 10% to 15%). The short regression phase between the former and the latter is the catagen phase (<1%). The length of each phase is characteristic for each anatomic site. For example, scalp hair is characterized by a 2- to 6-year anagen phase, and a 3-month telogen phase. The growth cycle of the 100,000 scalp hair is asynchronous. The daily growth rate is approximately 0.3 mm (1 cm per month), and 50 to 200 hairs are physiologically shed per day. Resulting hair length is determined by the lengths of the anagen and telogen phases.

Hair Follicle Structure

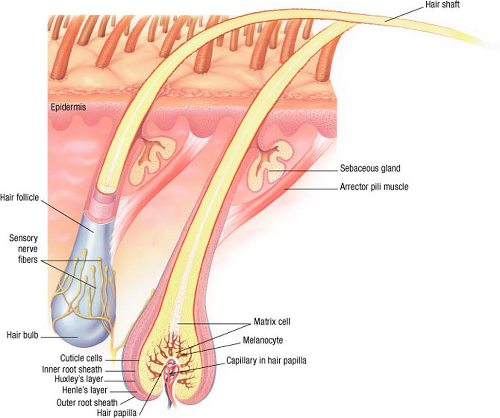

The hair follicle is a specialized skin appendage, which can be seen as an invagination of the epidermis that forms the outer root sheath and, in anagen hair, the inner root sheath. The epithelial root sheath is surrounded by connective tissue, the fibrous root sheath. Hair follicles are a reservoir for epithelial and melanocytic stem cells, contain a pigmentary unit for hair shaft pigmentation, and display special immunologic and anti-infection defenses. The hair follicle is comprised of an upper segment consisting of the follicular infundibulum, the isthmus, the sebaceous gland, and the arrector pili muscle, and an impermanent lower segment consisting of the bulb and the suprabulbar area (Fig. 24-1). The impermanent part is present only during anagen. The bulb is the thickest part of the follicle and contains the proliferating pool of undifferentiated cells, which give rise to the various layers. The majority of cell divisions can be found in the lower part of the bulb. At the constriction

above the bulb, the differentiation process begins and about halfway up the follicle the cells begin to die and cornify. The hair is fully hardened as it emerges from the follicle.

above the bulb, the differentiation process begins and about halfway up the follicle the cells begin to die and cornify. The hair is fully hardened as it emerges from the follicle.

Hair Loss (Alopecia)

The importance of human hair in view of social communication and sexual attraction is enormous. Thus, diseases that lead to hair loss may be accompanied by a diminished sense of self-esteem, anxiety, depressive mood, and social withdrawal.

Disorders resulting in hair loss can be grouped into scarring (synonym: cicatricial) and nonscarring forms. Scarring forms are characterized by a pathophysiologic pathway leading to permanent destruction of hair follicular stem cell structure with loss of hair-producing attribute. In contrast, in nonscarring alopecia the hair follicle is not destroyed and hair regrowth generally follows periods of hair shedding. In both scarring and nonscarring alopecia, the distribution of hair loss can occur in a diffuse pattern over the whole scalp or in circumscribed patterns, affecting only a few well-demarcated areas.

The terms “effluvium” and “alopecia” are commonly used when describing hair loss. While effluvium typifies the process of hair shedding, alopecia is the final result of this hair loss. Both terms are not disease specific and do not give etiologic information regarding underlying hair loss. The following section is an introduction to the classification of hair loss. A summary of the major nonscarring alopecias will be followed by a brief overview of scarring alopecia.

Evaluation of Hair Problems

Evaluation of hair problems in the physician’s office includes the patient’s history, physical examination of the entire skin surface with its appendages (hairs and nails), and, if necessary, special procedures.

Patient’s History

Before starting the physical exam, it is helpful to have patients fill out a detailed history form. This should be reviewed with them during the consultation. As shown in Table 24-1, details of the patient’s hair problem, personal health history, hair care, and the family history must be carefully considered.

Table 24-1 Questionnaire for Evaluation of Hair Problems | |

|---|---|

|

Physical Examination

Physical examination should include the entire scalp and the rest of the cutaneous surface if appropriate. Important information includes hair distribution and density, color, length, thickness, curliness, and texture. The shape and location of the frontal line should be noted. Furthermore, pathologic findings with regard to the appearance and texture of both skin and nails should be recorded. Any primary and secondary cutaneous lesions in their relationship to the follicles must be noted.

Special Procedures

Pull Test

The examiner grasps approximately 50 to 60 hairs and tugs at them from proximal to distal end. Removal of six hairs indicates a positive pull test and active shedding. However, the test can be considered positive if three hairs can be pulled out in several different areas of the scalp. The proximal ends can be examined against a white background for dark hair, or a black background for light hair. A blunt tip indicates hair breakage; a tapered tip can indicate regrowth or miniaturized hairs. The proximal end of the hair shafts may also be examined with a light microscope to determine if the hairs broke off (blunt ends) or came out as club hairs (telogen hair).

Biopsy

A scalp biopsy is necessary when confirming the diagnosis of scarring alopecia. Recommendations developed at the consensus meeting on cicatricial alopecia in 2001 are given here. One 4-mm punch biopsy including subcutaneous tissue should be taken from a clinically active area, processed for horizontal sections. A second 4-mm punch biopsy from a clinically active disease-affected area should be cut vertically into two equal pieces. One half provides tissue for transverse cut routine histologic sections; the other half can be used for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies (requires special transport media). Usually only one biopsy from the affected area is necessary for the diagnosis of a nonscarring alopecia; the samples are preferably processed with horizontal sections.

Nonscarring Alopecia (Telogen Effluvium)

|

A 44-year-old man presents with a complaint of “I’m losing hair all over my scalp. It’s just falling out over the past several months” (Fig. 24-2). He has severe atopic dermatitis, which is currently well controlled with topical corticosteroids and is otherwise healthy. He has recently had significant stressors in his life. Which alopecia would you diagnose his hair loss as?

Background

Telogen effluvium is a form of hair loss resulting from the sudden conversion of large numbers of anagen hair into telogen hair. A subsequent shedding that can last for several months indicates that the conversion did not occur all at once. Telogen effluvium is followed by an initiation of a new hair cycle 3 to 6 months later if the initiating trigger is eliminated. The molecular mechanisms and signals that switch the hair into a resting phase are still unknown.

Pathogenesis

Detailed information of molecular mechanisms and signals that switch the hair follicle apparatus from actively growing anagen stage to the resting

telogen are still not known. On the basis of clinical observations that telogen effluvium followed severe illness or emotional stress and was sometimes seen in association with thyroid dysfunction, it is believed that systemic signals, such as endocrine, neural, or nutritional signals, may play a role in the initiation of apoptosis in the anagen follicle (Table 24-2).

telogen are still not known. On the basis of clinical observations that telogen effluvium followed severe illness or emotional stress and was sometimes seen in association with thyroid dysfunction, it is believed that systemic signals, such as endocrine, neural, or nutritional signals, may play a role in the initiation of apoptosis in the anagen follicle (Table 24-2).

Key Features

Telogen effluvium is a nonscarring alopecia.

It results from a sudden conversion of large numbers of actively growing anagen follicles to telogen due to a yet not completely understood molecular signal which leads to diffuse hair shedding.

It is seen following severe illness, surgery, nutritional deficiency, iron deficiency, childbirth, in association with certain medications, and in patients with thyroid disease.

The process is reversible once the initiating factor is eliminated.

Table 24-2 Causes of Telogen Effluvium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Presentation

Telogen effluvium is characterized by moderate or massive shedding of telogen hair (Fig. 24-2). The patients usually report that they find hair all over the house, on the pillow, on the floor, or in their food. Oftentimes, patients bring in a bag of collected hair (“bag sign”). It is important to ask the patient for how long they collected the hair to get an idea about the activity of the condition. A decrease in hair density is often difficult to appreciate, especially during the first visit. Thinning occurs on the entire scalp; however, it is most noticeable in the frontotemporal and lateral parietal areas. Patients may report a 20% to 50% decrease of their ponytail diameter. The shedding usually starts 2 to 3 months after the initiating trigger. The severity of drug-induced hair loss tends to be dose-related.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of telogen effluvium is based on patient history and a clinical picture of diffuse hair thinning. Patient history should include questions about the duration of effluvium, distribution of hair loss, and whether severe life events/illness occurred 2 to 3 months before the shedding. A thorough drug history can reveal triggering medications. To rule out iron deficiency and thyroid

dysfunction, ferritin and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) should be ordered. A hair pull test should be performed on every patient. If three or more hairs can be pulled out in different areas of the scalp, telogen effluvium can be suspected. A scalp biopsy may help to confirm the diagnosis and should be performed if the diagnosis is in question.

dysfunction, ferritin and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) should be ordered. A hair pull test should be performed on every patient. If three or more hairs can be pulled out in different areas of the scalp, telogen effluvium can be suspected. A scalp biopsy may help to confirm the diagnosis and should be performed if the diagnosis is in question.

Patients should be referred to a specialist when telogen effluvium seems to be associated with therapy-resistant thyroid dysfunction or iron deficiency.

The primary care physician or internist should be involved if patients are exposed to drugs that are associated with telogen effluvium.

Differental Diagnosis

Male and female pattern hair loss

Diffuse alopecia areata

Therapy

Telogen effluvium can be a very distressing experience for the patient. It is important to reassure the patient that he or she will not go bald and that the condition will likely resolve once the trigger is found and eliminated. In cases of iron deficiency or thyroid dysfunction, iron or thyroid hormone replacement therapy usually results in a reversal of the alopecia. When recognizing a connection of telogen hair loss and the use of a possibly triggering medication, a switch to another drug is indicated, if possible. Minoxidil 2% for women and 5% for men can be considered for treatment as well, especially if the patient is not able to eliminate the triggering medication or if the trigger cannot be identified.

“At a Glance” Treatment

If iron deficiency or thyroid dysfunction is identified, appropriate supplementation in most cases will resolve the hair loss

TE caused by acute stress or illness will resolve once the trigger is resolved/eliminated

Identify offending medications and discontinue

Consider minoxidil 2% for women and 5% for men

Hair loss related to iron deficiency or thyroid dysfunction.

Drug-related telogen effluvium.

Course and Complications

Telogen effluvium is usually a self-limited form of hair loss, with initiation of a new hair cycle 3 to 6 months later once the causing trigger is eliminated. Chronic telogen effluvium may be caused by multiple triggers; however, in many patients with prolonged hair loss, the triggers are difficult to identify.

ICD9 Codes

| 704.00 | Alopecia, unspecified |

| 704.02 | Telogen effluvium |

Androgenetic Alopecia (Syn. Male and Female Pattern Hair Loss)

|

A 22-year-old man presents for evaluation, accompanied by his father. He noticed a frontoparietal recession of his hairline, as well as thinning at the crown in the past year (Fig. 24-3). His 45-year-old father presents with baldness in the parietal areas and remaining hair in a horseshoe-shaped rim around the scalp.

Background

Androgenetic alopecia has a postpubescent onset and can be seen as a genetically determined event in the lives of 50% of all men and around 38% of all women. It is the most common form of alopecia. The development and occurrence of androgenetic alopecia depends on the genetic predisposition and an interaction of endocrine factors.

Clinical hallmarks are the reduction of scalp hair density due to conversion of terminal to vellus-like hair and an increase of telogen hair under the influence of androgens (DHT). Severity and distribution among individuals with androgenetic alopecia varies considerably from slight scalp hair thinning to complete baldness in the parietal areas with a remaining horseshoe pattern. Distribution and amount of androgen-stimulated hair in other body areas is not related to the degree of hair loss on the scalp.

Key Features

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is the most common form of hair loss.

AGA presents as a nonscarring hair loss condition under the influence of androgens (dihydrotestosterone; DHT).

Clinical characteristics include a reduction of terminal hair density on the scalp, following a typical pattern in both genders, with a conversion of terminal to vellus-like hairs and an increase of telogen hair.

FDA-approved therapeutic options are topical minoxidil 2% (women), 5% (men) and oral finasteride 1 mg daily (men). Hair restoration surgery and low-level laser light may be considered as well.

Pathogenesis

The complete pathogenesis of male pattern hair loss has still not been completely established, though contributing risk factors such as genes, hormones, and other environmental aspects have been widely investigated. On the basis of clinical, chemical, and histopathologic studies, it was found that follicles became progressively smaller in size (miniaturization) and have shorter periods of growth. This process is androgen dependent and androgen-converting enzymes seem to play a crucial role. 5-Alpha-reductase converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Two enzyme subtypes are known, of which type II predominates in the hair follicles of the scalp, beard, and chest hair as well as the liver and prostate. Increased enzyme activity is followed by elevated levels of DHT. Female pattern hair loss is believed to be androgen-mediated as well, but with modified clinical presentation due to female genetic factors and converting enzymes and aromatase concentration in the frontal hairline. Even though androgens are essential for the process of male pattern hair loss, there is no difference in the excretion of ketosteroids or the blood levels of testosterone between balding and nonbalding individuals.

With regard to the modus of inheritance, it has been suggested that this is polygenic with a variable level of penetrance; however, recent publications also described a gene locus on chromosome 20 that has been associated with hair loss. The gene for the androgen receptor is known to be on the X-chromosome.

Clinical Presentation

Androgenetic alopecia describes a nonscarring form of scalp hair effluvium that occurs in a well-defined pattern. There is great inter-individual variation in the amount of hair loss and also with regard to concerns about it.

In men, the hair loss usually starts in the frontal region with recession of the hairline, followed by involvement of the crown with further progress (Fig. 24-3). In final stages, a horseshoe-shaped rim of hair around the scalp is characteristic. In addition to the pattern of loss, there is a decrease in length that can be observed along with a decreased thickness of the hair shafts in balding areas; follicular openings remain intact. Fine vellus-like hair can still be seen in balding areas. In the course of years to decades severe hair loss may occur, but there is always some remaining hair growth in a horseshoe-like pattern in the temporal and occipital areas. Body hair is not affected. In the 1950s, Hamilton classified the patterns of baldness based on frontal and frontotemporal recession and vertex thinning, later revised by Norwood, creating seven categories that are shown in Fig. 4A (Fig. 24-4).

Figure 24-3 Androgenetic alopecia of the vertex scalp.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|