Facial Laceration Emergency Room Closure Techniques

Christina Marie Pasick

Peter J. Taub

DEFINITION

Facial soft tissue injuries are commonly encountered in the emergency room. Common etiologies are motor vehicle collisions, animal bites, sports and job-related injuries, and interpersonal violence.

These injuries are often complex and may have significant impact on the patient’s facial form and function.

Plastic surgeons are often consulted by the emergency room physician or requested by the patients themselves for facial injuries ranging from simple lacerations to complex craniofacial trauma.

ANATOMY

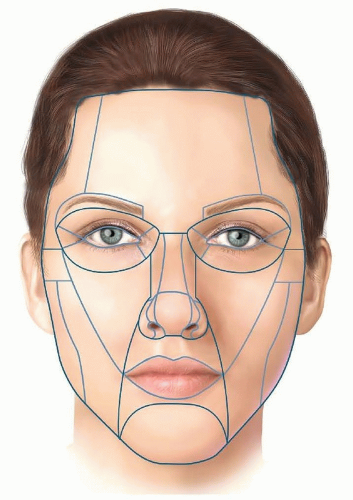

Facial aesthetic subunits should be considered when planning reconstruction so that incisions lie within or along the border of the involved subunit (FIG 1).

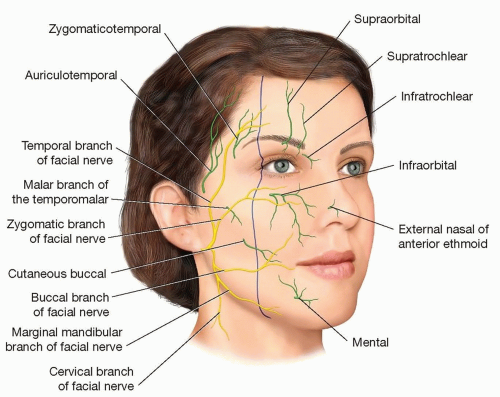

Lacerations deep to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) risk injury to the facial nerve branches. See Table 1 for physical exam findings in injured facial nerve branches.

Blunt injuries to the face may cause a temporary neuropraxia to the nerve that does not require immediate operative measures but instead should be observed for 3 weeks.

Extensive branching and cross-innervation of the branches of the facial nerve is present medial to the lateral canthus (FIG 2). As a general rule, lacerations of the nerve medial to the lateral canthus do not require repair. However, lacerations to the marginal mandibular nerve medial to the lateral canthus of the eye should be repaired, as there is not adequate crossover for functional recovery of the depressor muscles following medial injury to the marginal mandibular nerve. The temporal branch is another facial nerve branch with minimal crossover, but this nerve will most likely have innervated its target muscles (frontalis) should a laceration occur medial to the lateral canthus.

The sensory nerves of the face can be utilized as guidelines for local anesthesia nerve blocks. Suspicion for nerve laceration should be elevated when lacerations are present in these regions.

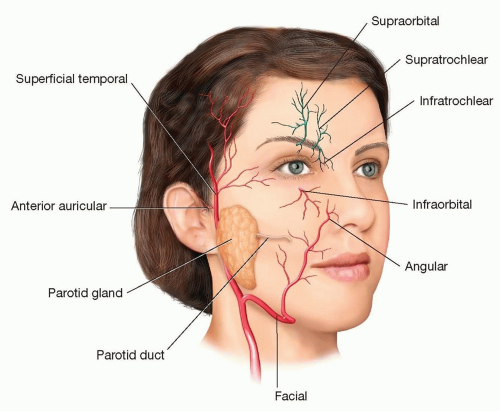

Knowledge of the location of the major arteries of the face can raise suspicion for lacerated vessels in deep wounds in these locations (FIG 3).

The parotid duct or Stensen duct lies in the line drawn between the tragus and the middle of the upper lip. Stensen duct empties into the mouth at the buccal mucosa overlying the second maxillary molar.

PATHOGENESIS

The mechanism of injury (ie, motor vehicle collision) can help to gauge the force involved in creating the injury and help determine if additional radiographic studies are necessary.

Suspect a larger area of tissue injury when dealing with a crush wound as opposed to a simple laceration.

Human bites should all be treated as contaminated wounds, and the need for careful irrigation and prophylactic antibiotics apply.

Table 1 The Physical Exam Findings Behind Injuries of the Facial Nerve Branches

Facial Nerve Branch Injured

Weakness Observed on Physical Exam

Temporal branch

Inability to elevate eyebrow

Zygomatic branch

Inability to close eye

Buccal branch

Inability to elevate upper lip

Marginal mandibular branch

Cervical branch

Inability to evert lower lip

Inability to activate platysma

Organisms often found in human mouths include Eikenella, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus viridans, and Bacteriodes.1

If the initial injury is not treated and the patient presents with a developed infection, inpatient therapy with IV antibiotics is often warranted, with a low threshold for OR debridement and washout.

Dog bites are the most common type of animal bite in the emergency room and are often contaminated with various bacteria, including Pasteurella multocida, Bacteroides, S viridans, and Capnocytophaga.1

Infection rates are not as high as seen in cat bites due to lower bacterial levels and the open avulsion-type injury seen in dog attacks rather than the deep puncture injury in cat bites that can trap bacteria. These open wounds facilitate irrigation.

Crush component of dog bites often results in substance loss and requires debridement and reconstruction of avulsed tissue.2

High incidence in the pediatric population.3

Cat bites should always be considered heavily contaminated wounds, as the nature of the long and narrow cat teeth lead to deeply penetrating wounds with a very narrow orifice, resulting in seeding of bacteria into deep structures.

Organisms often found include Pasteurella multocida and Bartonella henselae.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Trauma patients require a primary trauma survey and secondary trauma evaluation immediately.

The patient should be assessed for more serious intracranial, ophthalmologic, and cervical spine injuries.

Suspect skull base fracture with the following signs: raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis), battle sign (postauricular ecchymosis), otorrhea, or hemotympanum.

Take a complete history.

The etiology and timing of the wound

Other medical problems that may put the patient at risk for wound healing difficulties

Medications that may make the patient a bleeding risk

Smoking status

Tetanus vaccination history

Physical examination

Remove all clothing, jewelry, dried blood, and foreign material that may obscure the examination.

Use a systematic approach, inspecting for lacerations, avulsions, “road rash,” and areas of edema or ecchymosis.

Palpate wounds for bony step-offs to clue into underlying fracture.

To rule out Le Fort fracture, depress the maxilla bilaterally with your thumbs to feel for mobility. If mobile, proceed to grasp the maxillary teeth with one hand while holding the nasal spine in place with the other hand. Movement of the dental alveolus points toward a Le Fort I fracture, whereas movement of the nasal bridge points toward a Le Fort II or III fracture.

Check for involvement of deeper structures: muscle, nerve, artery, bone, joint.

Especially in bite wounds with fangs, the deeper structures may be injured.

Irrigation of the base of the wound provides more thorough visualization.

Sensory test for nerve involvement:

V1 ophthalmic branch: provides sensation to the forehead

V2 maxillary branch: provides sensation to the cheek

V3 mandibular branch: provides sensation to the lower third of the face/chin

Motor test for facial nerve involvement:

Test for weakness in the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) quickly and effectively by asking the patient to raise the eyebrows, close eyes, smile, puff out cheeks, and evert lower lips.

Assess for crepitus (subcutaneous emphysema) in bite wounds that would indicate an infection forming along the deeper fascial planes.

Examine all wounds for foreign body contaminants.

IMAGING

If facial fractures are suspected, a CT scan should be performed.

Plain x-ray or CT scan is helpful in determining the presence and location of foreign bodies within the wound.

Ultrasound may prove as a quick and reliable tool for locating foreign body without the side effects of radiation.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative, or nonsurgical, management may occur in cases with very superficial and noncontaminated lesions, where washout, debridement, and closure are not necessary.

Small wounds may have a preferred aesthetic outcome when allowed to close secondarily.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

It is important to emphasize to the patient that any fullthickness injury to the skin will result in a scar.

The type of scar that forms can be dependent on multiple factors and is largely based on genetic predisposition.

To maximize the chance of forming a fine-lined scar:

Most wounds require irrigation and debridement and closure in layers.

An early and tension-free closure of lacerations is a main priority.

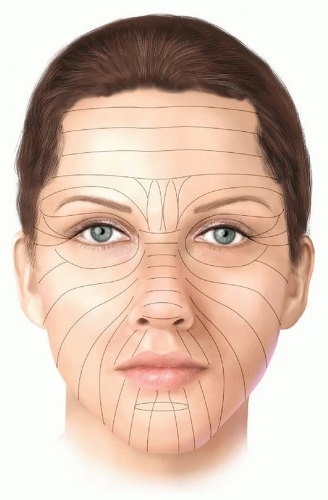

Aim to close the wound in the direction of Langer lines, the relaxed skin tension lines of the face (FIG 4).

Find Langer lines in younger patients by asking them to animate their faces; the resultant skin folds simulate Langer lines.

Delaying closure beyond 8 hours may increase the risk of infection of the wound bed and compromise aesthetic results, as swelling obscures anatomical landmarks.4

Preoperative Planning

Use emergency room anesthesia: create a comfortable environment for the surgeon and the patient.

Topical anesthetic

Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream, composed of a mixture of 2.5% prilocaine and 2.5% lidocaine, is widely present in the emergency room—its effect is directly dependent on the time the cream has been on the skin.

Place cream on skin and cover with a Tegaderm (3M, St. Paul, MN) or other occlusive dressing for at least 45 minutes.

This often will need to be supplemented with local injected anesthesia but is a useful start for pediatric cases in which there is high anxiety associated with the local anesthesia.

Local injected anesthetics

Lidocaine: most commonly used form of anesthesia in the ED. Maximum safe dose is 4.5 mg/kg. Effect usually lasts for 2 hours.

Epinephrine 1:100 000 may be added to the lidocaine solution to prolong the duration of its effect (to 4 hours) and reduce the amount of local anesthesia needed by reducing its diffusion away from the wound.

When epinephrine is added to lidocaine, the maximum safe dose is raised to 7 mg/kg.

Epinephrine takes about 7 to 15 minutes to take effect.

It was previously believed that epinephrine should not be used around end arteries such as the nose and stellate lacerations but is now accepted as safe practice.

Bicarbonate may be added to local anesthesia in the awake patient to reduce the burning pain on injection by raising the pH of the acidic lidocaine solution.

Bicarbonate also increases the effectiveness of the local anesthetic by favoring the nonionized form of the molecule, which passes through the cell membrane more easily.

Add 1 cc of 1 mEq/mL bicarbonate for every 9 cc of local anesthetic.

Bupivacaine: a longer-acting anesthetic, which may be added to the solution per the surgeon’s discretion

Max safe dose: 2.5 mg/kg. Effect usually lasts 4 hours. When epinephrine is added, max safe dose is raised to 3 mg/kg, and the effect is prolonged to 8 hours.

Improve comfort on injection: warm the local anesthetic solution, use a higher-gauge (smaller caliber) needle, inject through wound instead of through skin

Nerve blocks

For large lacerations in a single nerve distribution, nerve blocks can be effective and reduce the tissue distortion, which results when a large amount of local anesthetic is given as a field block.

Conscious sedation

Beneficial for pediatric patients who are uncooperative, making repair of facial lacerations difficult.

Helps to make the repair safer and reduces emotional trauma to the patient.5

This requires continuous monitoring of vital signs, requiring a nurse to be present throughout.

For pediatric cases, a combination of ketamine and versed are commonly used.

Ketamine: analgesic and amnestic agent

Pediatric dosing: 6 to 10 mg/kg PO once, 30 minutes prior to procedure; or 0.5 to 2 mg/kg IV once at start of procedure

Versed: sedative-hypnotic and amnestic agent

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree