Epidermal Nevi

Epidermal nevi are hamartomatous growths of the epidermis that are present at birth in about half of patients or develop early in childhood. The term epidermal nevus includes several entities, including keratinocytic epidermal nevi, nevus sebaceus, and nevus comedonicus, depending on which epidermal cell or structure comprises the lesion. Epidermal nevi of all types are considered an expression of cutaneous mosaicism with genetic mutation in the affected skin. Lesions follow the lines of Blaschko, suggesting that they represent postzygotic mutations. Some syndromes have also been included in this classification, such as Proteus, CHILD, and phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica (a RASopathy with reported HRAS and KRAS mutations), and both localized lesions and systematized presentations may be caused by the same genetic mutations. In general, larger lesions, more widespread lesions, and lesions of the head and neck are more likely to have associated internal complications. The combination of an epidermal nevus and an associated internal problem is termed epidermal nevus syndrome. For each histologic type, the frequency and nature of associated systemic problems may be characteristic. Overall, about 1 in 1000 children have an epidermal nevus of some type.

Keratinocytic Epidermal Nevi

Keratinizing epidermal nevi are the most common type of epidermal nevus and are described by a great variety of terms, such as linear epidermal nevus, hard nevus of Unna, soft epidermal nevus, and nevus verrucosus (verrucous nevus). If the lesion is widespread on half the body, the term nevus unius lateris has been used. The term ichthyosis hystrix is used if the lesions are bilateral and widespread.

The most common pattern of keratinocytic epidermal nevus is linear epidermal nevus. The individual lesions are verrucous, skin-colored, dirty-gray, or brown papules, which coalesce to form a serpiginous plaque ( Fig. 29.1 ). Interspersed in the localized patch may be horny excrescences and rarely comedones. The age of onset of epidermal nevi is generally at birth, but they may also develop within the first 10 years of life. They follow the lines of Blaschko.

The histologic changes in the epidermis are hyperplastic and affect chiefly the stratum corneum and stratum malpighii. There is variable hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. Up to 62% of biopsies of epidermal nevi have this pattern, so-called nonepidermolytic epidermal nevi. About 16% show epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. At times, other histologic patterns may be found, including a psoriatic type, an acrokeratosis verruciformis–like type, and a Darier disease–like type. It is assumed that each of these types would be associated with a specific mutation in the affected skin that, if widespread, would give rise to the cutaneous disorder with the same histology. For example, epidermal nevi that show epidermolytic hyperkeratosis would have the same gene mutation as the disorder of cornification, bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (i.e., keratins K1 and K10). In fact, patients with this type of epidermal nevus may have gonadal mosaicism that can result in offspring with the full-blown disorder. In a significant portion of the classic and common keratinocytic epidermal nevi that simply shows hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis histologically, there is an activating gene mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), HRAS, or PIK3CA, a downstream effector of FGFR signaling. FOXN1 is highly expressed in these lesions. These same gene mutations are found in sporadic seborrheic keratoses, which, not surprisingly, have the same histology.

Keratinocytic epidermal nevi may be associated with skeletal abnormalities and central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. CNS manifestations appear to be more common when the lesions are large and located on the head and neck. Large keratinocytic epidermal nevi of the trunk and extremities are more frequently associated with skeletal abnormalities. Because both nevus sebaceus and keratinocytic epidermal nevi were included in the original and large reports of epidermal nevus syndrome, the precise characterization of the “keratinocytic epidermal nevus syndrome” remains to be defined.

Both Proteus syndrome and CLOVE syndrome (congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi) can have skin lesions of epidermal nevus. CLOVE is distinguished from Proteus syndrome by congenital overgrowth of a ballooning nature, which grows proportionately with the patient and typically affects the feet.

The CHILD syndrome and verruciform xanthoma are both characterized by the presence histologically of elongated and widened dermal papillae filled with xanthoma-like cells. Epidermal hyperplasia, with acanthosis, papillomatosis, parakeratosis, and hyperkeratosis, is also present (the features of a keratinocytic epidermal nevus). In rare cases, instead of half the body being affected, large quadrants of the body, favoring folds, are the sites of the epidermal growths (ptychotropism). CHILD and verruciform xanthoma (in some cases) contain mutations in the NSDHL gene, located on the X chromosome and required for cholesterol biosynthesis.

Epidermal nevus syndrome associated with FGFR3 mutation is characterized by widespread epidermal nevus and developmental brain defects. Epidermal nevus syndrome may also be associated with vitamin D–resistant hypophosphatemic rickets, perhaps from circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) acting as a phosphaturic.

Rarely, malignancies occur in keratinocytic epidermal nevi or in other organs. Any newly appearing lesion within a stable epidermal nevus should be biopsied to exclude this possibility. Management of keratinocytic epidermal nevi is difficult because, unless the treatment extends into the dermis (and thus may cause scarring), the lesion recurs. The use of a combination of 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus 0.1% tretinoin creams once daily may be beneficial, and the response may be enhanced by occlusion. Cryotherapy can be quite effective, with good cosmetic results. Corticosteroids or a combination of a topical corticosteroid and calcipotriene may be beneficial. Carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) and erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) laser treatment may also be effective. If the lesion is small, simple excision can be considered.

Akingboye A, et al: Papillary transitional cell bladder carcinoma and systematized epidermal nevus syndrome. Cutis 2017; 99: 61.

Gantner S, et al: CHILD syndrome with mild skin lesions. J Cutan Pathol 2014; 41: 787.

Koh MJ, et al: Systematized epidermal nevus with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis improving with topical calcipotriol/betametasone dipropionate combination ointment. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30: 370.

Om A, et al: Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica. Pediatr Dermatol 2017; 34: 352.

Yarak S, et al: Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a multiple verrucous epidermal nevus. An Bras Dermatol 2016; 91: 166.

Nevus Comedonicus

Nevus comedonicus is characterized by closely arranged, grouped, often linear papules that have at their center dilated follicular openings with keratinous plugs resembling comedones. Cysts, abscesses, fistulas, and scars develop in about half the cases, which have been described as “inflammatory” nevus comedonicus. As with other epidermal nevi, lesions may be localized to a small area or may have an extensive distribution. They are most frequently unilateral, although bilateral cases are also seen. Lesions occur mostly on the trunk and follow the lines of Blaschko. The lesions may develop any time from birth to age 15 but are usually present by age 10. Follicular tumors, including trichofolliculoma and pilar sheath acanthoma, can appear within the lesion. An “epidermal nevus syndrome” or “nevus comedonicus syndrome” has been reported with electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities, ipsilateral cataract, corneal changes, and skeletal anomalies (hemivertebrae, scoliosis, and absence of fifth ray of hand).

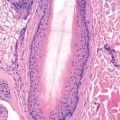

The pilosebaceous follicles are dilated and filled with keratinous plugs ( Fig. 29.2 ). On the palms, pseudocomedones are present. Histologic examination reveals large dilated follicles filled with orthokeratotic horny material and lined by atrophic squamous epithelium. The interfollicular epidermis is papillomatous, as seen in typical epidermal nevi. Hair follicle differentiation, well-formed follicular structures, and normal sebaceous glands are not common in well-formed lesions.

Somatic mutations in NEK9 are frequently associated. Apert syndrome is characterized by skeletal anomalies and acne. It is caused by a mutation in FGFR2. A mutation has also been found in FGFR2 in at least one case of nevus comedonicus, suggesting that nevus comedonicus may be a mosaic form of Apert syndrome.

Treatment of lesions not complicated by inflammatory cysts and nodules is primarily cosmetic. Pore-removing cosmetic strips and comedone expression may improve the cosmetic appearance. Topical tretinoin may be beneficial, as may Er:YAG or CO 2 laser. Patients with inflammatory lesions are much more difficult to manage. If the area affected is limited, surgical excision may be considered. Oral isotretinoin, chronically at the minimum effective dose (0.5 mg/kg/day, or less if possible), may partially suppress the formation of cysts and inflammatory nodules; however, many cases of nevus comedonicus fail to respond. The comedonal lesions do not improve with oral isotretinoin.

Chiriac A, et al: Extensive unilateral nevus comedonicus without genetic abnormality. Dermatol Online J 2016 Sep 15; 22.

Ferrari B, et al: Nevus comedonicus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015; 32: 216.

Levinsohn JL, et al: Somatic mutations in NEK9 cause nevus comedonicus. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 98: 1030.

Polat M, et al: Bilateral nevus comedonicus of the eyelids associated with bladder cancer and successful treatment with topical tretinoin. Dermatol Ther 2016; 29: 479.

Tchernev G, et al: Nevus comedonicus. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2013; 3: 33.

Zhu C, et al: Ultrapulse carbon dioxide laser treatment for bilateral facial nevus comedonicus. Dermatol Ther 2017; 30.

Epidermal Nevus Syndrome

Epidermal nevus syndrome does not represent a single entity, but rather multiple syndromes characterized by keratinocytic or organoid nevi, at times associated with internal organ involvement. Each variant has characteristic cutaneous findings and at times relatively specific internal findings. There are at least five variants of organoid epidermal nevus syndrome:

- 1.

Schimmelpenning syndrome ( Fig. 29.3 ). Nevus sebaceus coexists with cerebral, ocular, and skeletal defects. Lesions of the head and neck may lack prominent sebaceous hyperplasia. Coloboma and lipodermoid of the conjunctiva can occur. Vitamin D–resistant hypophosphatemic rickets may be present.

Fig. 29.3

Schimmelpenning syndrome.

- 2.

Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica. Nevus sebaceus and papular nevus spilus coexist. The nevus sebaceus may have a flat, erythematous central area with an elevated margin showing features of a nonorganoid epidermal nevus. Multiple angiomas may be found in the nevus spilus component. True basal cell carcinomas develop in the nevus sebaceus of this syndrome. CNS complications can occur, along with hyperhidrosis, weakness, and sensory or motor neuropathy. Vitamin D–resistant rickets may also be present.

- 3.

Nevus comedonicus syndrome. Nevus comedonicus with ipsilateral ocular, skeletal, or neurologic defects defines this syndrome.

- 4.

Angora hair nevus syndrome. A linear epidermal nevus is covered with long, white hair growing from dilated follicular pores. CNS, eye, and skeletal abnormalities may be found.

- 5.

Becker nevus syndrome. Becker nevus is associated with ipsilateral hypoplasia of the breast.

Keratinocytic nevi are seen in at least four epidermal nevus syndromes:

- 1.

Proteus syndrome.

- 2.

Type 2 segmental Cowden disease. A linear soft, thick, papillomatous keratinocytic nevus in the absence of cerebriform hyperplasia of the palms and soles, but with segmental glomerulosclerosis. It is caused by loss of heterozygosity in an embryo carrying a PTEN germline mutation. Associated anomalies include lipomas, connective tissue nevi, vascular nevi, hemihypertrophy, seizures, hydrocephalus, and gastrointestinal (GI) polyps.

- 3.

CHILD syndrome. X-linked dominant, male lethal trait. It is caused by a mutation in NSDHL. Chondrodysplasia punctata is characteristic. There is a marked affinity of the nevus for the body folds (ptychotropism). There is a tendency to spontaneous involution.

- 4.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 epidermal nevus syndrome (Garcia-Hafner-Happle syndrome). A velvety-type nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus and cerebral defects identify this syndrome.

Less well-defined syndromes include the following:

- 1.

Nevus trichilemmocysticus. Multiple trichilemmal cysts along Blaschko’s lines are associated with osteomalacia and fractures.

- 2.

Didymosis aplasticosebacea. Sebaceous nevus coexists with aplasia cutis, usually in close proximity to each other.

- 3.

SCALP syndrome: sebaceous nevus, CNS malformations, aplasia cutis congenital, limbal dermoid, and pigmented nevus. It is a combination of didymosis aplasticosebacea and a large melanocytic nevus.

- 4.

Gobellos syndrome: systematized, linear, velvety, orthokeratotic nevus with hypertrichosis and follicular hyperkeratosis. Multiple bony defects are present.

- 5.

Bafverstedt syndrome: horny excrescences in a linear pattern with mental retardation and seizures. Diffuse ichthyosis-like hyperkeratosis covers the entire body, including the palms and soles.

- 6.

NEVADA syndrome: keratinocytic, verrucous nevus with angiodysplasia.

- 7.

CLOVE syndrome: congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformation, and epidermal nevus. Extensive truncal vascular malformations and overgrown feet are characteristic.

Asch S, Sugarman JL: Epidermal nevus syndromes. Handb Clin Neurol 2015; 132: 291.

Happle R: The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63: 25.

Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus

The term inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) may encompass as many as four separate conditions, with some representing mosaicism for erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva. The most common form is the classic ILVEN, or “dermatitic” epidermal nevus. At least three quarters of these cases appear before age 5 years, most before age 6 months. Later onset in adulthood has been reported. ILVEN is characteristically pruritic and pursues a chronic course. Lesions follow the lines of Blaschko. The individual lesions comprising the affected region are erythematous papules and plaques with fine scale ( Fig. 29.4 ). The lesions are morphologically nondescript and, if the distribution is not recognized, could be easily overlooked as an area of dermatitis or psoriasis. Multiple, widely separated areas may be affected, usually on only one side of the body; this may also be bilateral, analogous to other epidermal nevi. Familial cases have been reported. Rarely, systemic involvement, with musculoskeletal and neurologic sequelae (developmental delay, epilepsy), has been reported.

Histologically, classic ILVEN demonstrates abruptly alternating areas of hypergranulosis with orthokeratosis, and parakeratosis with agranulosis. An inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes is present in the upper dermis. At times, the histology may simply be that of a subacute dermatitis. Although the histologic diagnosis of psoriasis can be considered, the correct diagnosis can be established if the dermatopathologist is made aware of ILVEN as a consideration. If there is a question, the presence of involucrin expression in the parakeratotic areas can distinguish ILVEN from psoriasis.

Three other types of inflammatory nevus have been included in this group. Some cases of “linear” lichen planus have been considered as “epidermal nevi,” because they typically follow lines of Blaschko. CHILD syndrome, also considered a type of “inflammatory” epidermal nevus, is usually clinically distinct, demonstrating its characteristic hemidysplasia. The most confusing entity has been the “nevoid” or “linear” psoriasis. These cases are of two types. The first type is a child with a family history of psoriasis who has a nevoid lesion at or near birth. The child later develops psoriasis that “koebnerizes” into the ILVEN lesion, suggesting it is a “locus minoris resistensiae” for psoriasis. Treatment of the psoriasis clears the psoriasis overlying the ILVEN, but not the ILVEN. Arthritis developed in one such patient. In the second type, psoriasis initially presents in one band or area. Histologically, it resembles psoriasis. Most of these patients develop typical psoriasis later in life, suggesting a mosaicism that allowed expression of the psoriasis earlier in the initially affected area.

Inflammatory LVEN is differentiated from other epidermal nevi by the presence of erythema and pruritus clinically and by histologic features. Lichen striatus can be distinguished by its histology and natural history. Topical corticosteroids and topical retinoids appear to have limited benefit in ILVEN. However, topical vitamin D (calcipotriol and calcitriol) and topical anthralin have been beneficial. Surgical modalities include excision, cryotherapy, and laser. In cases of “nevoid,” “linear,” or “blaschkolinear” psoriasis, acitretin, narrow-band (NB) ultraviolet (UV) B therapy, and calcipotriene have been beneficial, but etanercept has failed.

Conti R, et al: Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2013; 15: 242.

Hammami Ghorbel H, et al: Treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with 2940 nm erbium fractional laser. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 824.

Umegaki-Arao N, et al: Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with a postzygotic GJA1 mutation is a mosaic erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 967.

Wollina U, et al: ILVEN—Complete remission after administration of topical corticosteroid. Georgian Med News 2017; 263: 10.

Hyperkeratosis of the Nipple and Areola

Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola (HNA) is an uncommon, benign, asymptomatic, acquired condition of unknown pathogenesis. Women represent 80% of cases, and HNA presents in their second or third decade. In men, the time of presentation is variable. Most cases are bilateral, although unilateral cases can occur. In about half the cases, both the areola and the nipple are involved. Breastfeeding is usually not affected. Clinically, there is verrucous thickening and brownish discoloration of the nipple and/or areola. Histologically, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis occurs, with occasional keratinous cysts in the filiform acanthotic epidermis. The course is chronic. Treatment with cryotherapy, electrosurgical superficial removal of hyperkeratosis, excision and reconstruction, low-dose acitretin, topical steroids, radiofrequency ablation and calcipotriol have benefitted some patients. A similar clinical manifestation has been seen in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), malignant acanthosis nigricans, and candidiasis of the nipple associated with mucocutaneous candidiasis. Painful areolar hyperkeratosis may be seen as a complication of sorafenib therapy. HNA must be distinguished from acanthosis nigricans, pregnancy-associated hyperkeratosis of the nipple, nipple eczema with lichenification, and Darier disease. Isolated papules or small plaques in this location probably represent seborrheic keratoses affecting the nipple or areola. The relationship of HNA and areolar melanosis is unclear; these conditions have significant clinical similarity, except for the absence of hyperkeratosis in those lesions described as areolar melanosis.

Alonso-Corral MJ, et al: Nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple and the areola. Dermatol Online J 2016 Feb 17; 22.

Boussofara L, et al: Bilateral idiopathic hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat 2011; 20: 41.

Foustanos A, et al: Surgical approach for nevoid hyperkeratosis of the areola. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2012; 5: 40.

Higgins HW, et al: Pregnancy-associated hyperkeratosis of the nipple. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 722.

Clear Cell Acanthoma (Pale Cell Acanthoma)

Clear cell acanthoma is also known as Degos acanthoma. The typical lesion is a circumscribed, red, moist, shiny nodule with some crusting and peripheral scale ( Fig. 29.5 ); it is usually about 1–2 cm in diameter. A collarette of scale is usually observed, and there may be pigmented variants. Exophytic nodules have been reported. The favorite site is on the shin, calf, or occasionally the thigh, although other sites (e.g., abdomen, scrotum) have been reported. The lesion is asymptomatic and slow growing and can occur in either gender, usually after age 40. Solitary lesions are most common, but multiple nodules have been described, including the setting of Cowden syndrome. Rarely, an eruptive form of the disease occurs, producing up to 400 lesions. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising from clear cell acanthoma has also been reported. Lesions occurring in plaques of psoriasis on the buttocks have been described, and clear cell acanthoma on the nipple has been associated with chronic eczema, suggesting a possible inflammatory etiology.

The acanthotic epidermis consists of pale, edematous cells and is sharply demarcated. The basal cell layer is normal. Neutrophils are scattered within the acanthoma and in groups below and within the stratum corneum, a finding similar to the micropustules of psoriasis. The dermal blood vessels are dilated and tortuous, as seen in psoriasis. The clear keratinocytes abound in glycogen, staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS). Several centers have reported identification of human papillomavirus (HPV) in clear cell acanthomas, making distinction of these lesions from warts difficult. Clear cell acanthoma must be differentiated from eccrine poroma, which appears most frequently on the hair-free part of the foot, and from clear cell hidradenoma, which occurs most often on the head, especially the face and eyelids. Treatment is surgical, with cryotherapy, CO 2 laser, or excision.

Hidalgo-García Y, et al: Clear cell acanthoma of the areola and nipple. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2016; 107: 793.

Potenziani S, et al: Multiple clear cell acanthomas and a sebaceous lymphadenoma presenting in a patient with Cowden syndrome. J Cutan Pathol 2017; 44: 79.

Shahriari N, et al: In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy features of a large cell acanthoma. Dermatol Pract Concept 2016; 6: 67.

Shirai A, et al: Multiple clear cell acanthoma associated with multiple Bowen’s disease. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53: e386.

Tempark T, Shwayder T: Clear cell acanthoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012; 37: 831.

Waxy Keratoses of Childhood (Kerinokeratosis Papulosa)

Waxy keratoses of childhood is a genodermatosis that is either sporadic or familial. It may be generalized or segmental. Clinically, the lesions are keratotic, flesh-colored papules that affect the trunk and extremities. They appear before age 3 years. Histologically, there is papillomatosis with focal “church-spire” tenting of the epidermis and marked hyperkeratosis. The natural history of this rare disorder is unknown. Clinically and histologically, the lesions must be distinguished from warts.

Gönül M, et al: A case of waxy keratoses of childhood. Dermatology 2008; 217: 143.

Happle R, et al: Kerinokeratosis papulosa with a type 2 segmental manifestation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 50: S84.

Mehrabi D, et al: Waxy keratoses of childhood in a segmental distribution. Pediatr Dermatol 2001; 18: 415.

Multiple Minute Digitate Hyperkeratosis

Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis (MMDH) is a rare disorder. About half of cases are familial, inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, and the other half are sporadic. This condition has also been called digitate keratoses, disseminated spiked hyperkeratosis, minute aggregate keratosis, and familial disseminated piliform hyperkeratosis. Clinically, hundreds of tiny, asymptomatic digitate keratotic papules appear on the trunk and proximal extremities. They are not associated with follicular structures. Histologically, each lesion represents a spiked, digitate, or tented area of acanthotic epidermis with overlying orthohyperkeratosis. Similar lesions can be seen after inflammation and radiation therapy. The relationship of the familial/sporadic cases and the postinflammatory condition is unclear. In some adult patients, an underlying malignancy is found.

Caccetta TP, et al: Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: e49.

Pimentel CL, et al: Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002; 16: 422.

Acantholytic Acanthoma, Epidermolytic Acanthoma, Acantholytic Dyskeratotic Acanthoma

These three acanthomas represent benign, usually solitary, but at times multiple papules that are nondescript and may be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma (BCC), SCC, or HPV infection. Histologic examination shows epidermal hyperplasia with acantholysis resembling pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, or Hailey-Hailey disease. The condition multiple epidermolytic acanthoma usually occurs in the genital area and histologically resembles Hailey-Hailey disease. This probably represents a localized variant of that condition.

Jang BS, et al: Multiple scrotal epidermolytic acanthomas successfully treated with topical imiquimod. J Dermatol 2007; 34: 267.

Kazlouskaya V, et al: Solitary epidermolytic acanthoma. J Cutan Pathol 2013; 40: 701.

Minakawa S, et al: Acantholysis caused repeated hemorrhagic bullae in a case of acantholytic acanthoma. J Dermatol 2012; 39: 1107.

Warty Dyskeratoma

Warty dyskeratomas are usually solitary and are found on the head and neck (70%), trunk (20%), or extremities. Rare oral lesions occur. The lesion is a brown-red papule or nodule with a soft, yellow, central keratotic plug. Histologically, a cuplike depression filled with a keratotic plug is most common. The epithelium lining the invagination shows the features of Darier disease, with intraepidermal clefts, acantholytic cells, and pseudovilli. Keratin pearls, corps ronds, and grains may be seen. Cystic lesions with prominent keratinous cysts can occur, especially in the vulva. Cutaneous lesions appear to originate from a hair follicle. Warty dyskeratoma must be distinguished histologically from keratoacanthoma and acantholytic SCC. Acantholytic acanthoma has a similar histology, but dyskeratosis is absent, distinguishing it from warty dyskeratoma. Treatment is surgical.

Lencastre A, et al: Warty dyskeratoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: e97.

Torres KM, et al: Cystic acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. Indian Dermatol Online J 2016; 7: 272.

Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratoses are incredibly common and usually multiple. They present as oval, slightly raised, tan or light-brown to black, sharply demarcated papules or plaques, rarely more than 3 cm in diameter ( Fig. 29.6 ). They appear “stuck on” the skin, as if they could be removed with the flick of a fingernail. They are located mostly on the chest and back but also frequently involve the scalp, face, neck, and extremities. An inframammary accumulation is common. Occasionally, genital lesions are seen. The palms and soles are spared; “seborrheic keratoses” in these areas are usually eccrine poromas. The surface of the warty lesions often becomes crumbly, resembling a loosely attached crust. When this is removed, a raw, moist base is revealed. Seborrheic keratoses may be associated with itching. Some patients have hundreds of these lesions on the trunk. Although it had been thought that the age of onset is generally in the fourth to fifth decade, in Australia the prevalence of seborrheic keratoses was 20% in males and 25% in females age 15–25. Typical lesions of the trunk are much more common in white persons; however, the “dermatosis papulosa nigra” variant of the central face is common in African Americans and Asians.

The pathogenesis of seborrheic keratoses is unknown. Clinically, they usually originate de novo or appear initially as a lentigo. A sudden eruption of many seborrheic keratoses may follow an exfoliative erythroderma, erythrodermic psoriasis, or an erythrodermic drug eruption. These lesions may be transient. Seborrheic keratoses are more common in areas of sun exposure, including favoring the driver’s side in truck drivers. In about one third or more of cases, solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses both have gain-of-function mutations in FGFR3 and PIK3CA, the genes mutated in keratinocytic epidermal nevi. This supports the concept that some seborrheic keratoses begin as flat lesions that cannot be distinguished from solar lentigines.

Histologically, most seborrheic keratoses demonstrate acanthosis, varying degrees of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and at times, keratin accumulations within the acanthotic epidermis (pseudo–horn cysts). The epidermal cells lack cytologic atypia, except at times in the irritated variant, where typical mitoses may occur. Six histologic types are distinguished: hyperkeratotic, acanthotic, adenoid or reticulated, clonal, irritated, and melanoacanthoma. Poor correlation exists between the clinical appearance and the observed histology, unlike for inverted follicular keratosis, dermatosis papulosa nigra, and stucco keratosis, where the histologic features are characteristic and match the clinical lesion. Melanoacanthoma differs from regular seborrheic keratosis by the presence of numerous dendritic melanocytes within the acanthotic epidermis. Oral melanoacanthoma, which has also been called melanoacanthosis, is clinically a reactive pigmented lesion seen primarily in young black patients (see Chapter 34 ). Many cases of inverted follicular keratosis represent irritated seborrheic keratoses. Some view granular parakeratotic acanthomas a variant of irritated seborrheic keratosis, and others see it as a separate entity.

The differential diagnosis usually poses no problems in most cases, but clinically atypical lesions can be a challenge. The most difficult, especially for the nondermatologist, is to differentiate the solitary black seborrheic keratosis from melanoma. The regularly shaped verrucous lesion is often different from the smooth-surfaced and slightly infiltrating pattern of melanoma. Dermoscopy can sometimes be of great value; at other times, however, seborrheic keratoses may demonstrate dermatoscopic features typical of melanocytic lesions, and the presence of horn cysts does not exclude a melanocytic lesion. Actinic keratoses are usually erythematous, more sharply rough, and slightly scaly. The edges are not sharply demarcated, and they occur most often on the face, bald scalp, and backs of the hands. Nevi may be closely simulated. Clonal seborrheic keratoses demonstrate intraepidermal nests suggestive of intraepidermal epithelioma of Jadassohn. Rarely, Bowen disease, SCC, BCC, trichilemmal carcinoma, or melanoma arises within typical-appearing seborrheic keratosis. Some of these may represent collision lesions, not cancers arising from seborrheic keratoses. It is prudent to biopsy any lesion that appears atypical, because even the most seasoned dermatologist has been humbled by the occasional diagnosis of melanoma in low-suspect lesions.

Seborrheic keratoses are easily removed with liquid nitrogen, curettage, or both, to avoid the need for local anesthesia to perform the curettage. The spray freezes the lesion to make it brittle enough for easy removal with the curette. Scarring is not produced by this method. Light freezing with liquid nitrogen alone is also effective, and most patients prefer it to simple curettage with local anesthesia mainly because of decreased wound care. Light fulguration and shave removal are other acceptable methods. A novel topical agent is in clinical trials.

Sign of Leser-Trélat

The sudden appearance of numerous seborrheic keratoses in an adult may be a cutaneous sign of internal malignancy. Sixty percent of the neoplasms have been adenocarcinomas, primarily of the GI tract. Other common malignancies are lymphoma, breast cancer, and SCC of the lung, but many other types have been reported. To be considered a case of Leser-Trélat, the keratoses should begin at approximately the same time as the development of the cancer, have a rapid onset, and run a parallel course in regard to growth and remission. The lesions are often pruritic, and acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms may accompany the appearance of the seborrheic keratoses of Leser-Trélat.

Al Ghazal P, et al: Leser-Trélat sign and breast cancer. Lancet 2013; 381: 1653.

Da Rosa AC, et al: Three simultaneous paraneoplastic manifestations (ichthyosis acquisita, Bazex syndrome, and Leser-Trélat sign) with prostate adenocarcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 538.

Heidenreich B, et al: Genetic alterations in seborrheic keratoses. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 36639.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

Dermatosis papulosa nigra occurs in about 35% of black persons and is also relatively common in Asians. It usually begins in adolescence, appearing first as minute, round, skin-colored or hyperpigmented macules or papules that develop singly or in sparse numbers on the malar regions or on the cheeks below the eyes. It has been described in patients as young as age 3. The lesions increase in number and size over time, so that over the course of years, the patient may have hundreds of lesions ( Fig. 29.7 ). These are distributed over the periorbital regions initially but may occur on the rest of the face as well as the neck and upper chest. Lesions do not spontaneously resolve. They closely simulate seborrheic keratoses. The lesions are asymptomatic and do not develop scaling, crusting, or ulceration.

Microscopically, the chief alterations are in the epidermis. Irregular acanthosis, papillomatosis, and deposits of uncommonly large amounts of pigment throughout the rete, particularly in the basal layer, are characteristic. Many believe this to be a form of seborrheic keratosis. This concept is supported by the finding of FGFR3 mutations in the lesions of dermatosis papulosis nigra, similar to those found in seborrheic keratoses.

Treatment is made difficult by the tendency for the development of dyspigmentation. Light curettage with or without anesthesia; light, superficial liquid nitrogen application; and light electrodesiccation are effective but may result in hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. KTP, CO 2 , and Nd:YAG lasers have been reported effective but not superior to simple electrodesiccation. Aggressive treatment should be avoided to minimize dyspigmentation and scarring.

Stucco Keratosis

Stucco keratoses have been described as “stuck on” lesions occurring on the lower legs, especially in the vicinity of the Achilles tendon. They are also seen on the dorsa of the feet, forearms, and dorsal hands. The palms, soles, trunk, and head are never affected. Varying in diameter from 1–5 mm, the lesions are loosely attached and thus can easily be scratched off. They vary in number from a few to more than 50. Stucco keratoses are common in the United States and Australia. They occur mostly in men over 40 years old. Histologically, the picture is that of a hyperkeratotic type of seborrheic keratosis, with no hypergranulosis and no wart particles seen on electron microscopy. The presence of PIK3CA mutations in stucco keratoses suggests they are a variant of seborrheic keratosis. The treatment, if required, consists of emollients, which soften the skin and cause the scaly lesions to fall off. Ammonium lactate 12% lotion may be effective in improving the appearance of the lesions. Stucco keratoses must be distinguished from Flegel disease.

Ali FR, et al: Carbon dioxide laser ablation of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Lasers Med Sci 2016; 31: 593.

Bruscino N, et al: Dermatosis papulosa nigra and 10,600-nm CO 2 laser, a good choice. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2014; 16: 114.

Garcia MS, et al: Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra in 10 patients. Dermatol Surg 2010; 36: 1968.

Hafner C, et al: FGFR3 and PIK3CA mutations in stucco keratosis and dermatosis papulosa nigra. Br J Dermatol 2010; 162: 508.

Veraitch O, et al: Early-onset dermatosis papulosa nigra. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174: 1148.

Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans (Flegel Disease)

Rough, yellow-brown, keratotic, flat-topped papules 2–5 mm in diameter and found primarily on the dorsal feet and lower legs are characteristic. The palms, soles, and oral mucosa may rarely be involved. Familial cases have been reported.

The histologic findings are distinctive, with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis overlying a thinned epidermis and irregular acanthosis at the periphery. A bandlike inflammatory infiltrate occurs in the papillary dermis. Topical emollients, topical keratolytics, topical corticosteroids, zinc bandages, topical 5-FU, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy have been reported useful. Oral retinoids may result in improvement but are difficult to justify in this chronic, asymptomatic condition except in rare severe cases. Both benefit and failure with topical vitamin D analogs have been reported. The lesions do not recur after shallow shave excision.

Krishnan A, Kar S: Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. J Dermatol Case Rep 2012; 6: 93.

Valdebran M, et al: Dermoscopic findings in hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: e211.

Benign Lichenoid Keratoses (Lichen Planus–Like Keratosis)

Benign lichenoid keratoses are usually solitary, dusky-red to violaceous, papular lesions up to 1 cm in diameter and at times larger ( Fig. 29.8 ). They occur most often on the distal forearms, hands, or chest of middle-aged white women. The lesions are typically biopsied because the clinical features are identical to those of a superficial BCC. A slight violaceous hue or the presence of an adjacent solar lentigo can raise the suspicion of lichen planus–like keratosis. Multiple lesions may simulate a photodermatitis, such as lupus erythematosus (LE). Evolution from preexisting solar lentigines is often noted histologically or by history, and the presence of the same underlying genetic mutations ( FGFR3, PIK3CA, and RAS ) supports this concept.

Histologically, the lesion may be indistinguishable from idiopathic lichen planus. Whereas idiopathic lichen planus rarely demonstrates parakeratosis, plasma cells, or eosinophils, these may be present in lichen planus–like keratosis. The remnants of a solar lentigo may be seen at the periphery. These features, plus the clinical information that this represents a solitary lesion, suggest the correct diagnosis. Clinical correlation is essential because similar histologic findings may be seen in lichenoid drug eruptions, acral LE, and lichenoid regression of melanoma. Direct immunofluorescence is positive, with clumped deposits of immunoglobulin M in a lichen planus–like pattern at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ). This differs from the continuous granular immunoglobulin deposition of acral LE. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is effective.

Chan AH, et al: Differentiating regressed melanoma from regressed lichenoid keratosis. J Cutan Pathol 2017; 44: 338.

Kim HS, et al: Clinical and histopathologic study of benign lichenoid keratosis on the face. Am J Dermatopathol 2013; 35: 738.

Arsenical Keratoses

Arsenical keratoses are keratotic, pointed, 2–4 mm, wartlike lesions on the palms, soles, and sometimes ears of persons who have a history of drinking contaminated well water or taking medications containing arsenic trioxide, usually for asthma (e.g., Fowler’s solution, Bell’s Asthma Mixture), atopic dermatitis, or psoriasis, often years previously ( Fig. 29.9 ). These lesions resemble palmar pits but may have a central hyperkeratosis. When the keratosis is picked off with the fingernails, a small, dell-like depression is seen.

Bowen disease (BD) and invasive arsenical SCC may be present, with the latent period being 10 and 20 years, respectively. The profound increase in BD and SCC appears to be characteristic of patients with arsenic exposure from well water. In patients exposed to arsenic through elixirs, BCCs are more characteristically seen. The latency period for development of BCC is also 20 years. Lesions are most common on the scalp and trunk. Arsenical keratoses may be a marker for increased lung and urothelial carcinoma.

Hsu LI, et al: Use of arsenic-induced palmoplantar hyperkeratosis and skin cancers to predict risk of subsequent internal malignancy. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177: 202.

Ruiz de Luzuriaga AM, et al: Arsenical keratoses in Bangladesh. Dermatol Clin 2011; 29: 45.

Son SB, et al: Successful treatment of palmoplantar arsenical keratosis with a combination of keratolytics and low-dose acitretin. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008; 33: 202

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers and Their Precursors

More nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) are diagnosed annually in the United States than all other cancers combined. In 2006 more than 3.5 million new NMSC cases were estimated to occur, and the incidence is rising. One in two men and one in three women in the United States will develop NMSC in their lifetime, usually after age 55. Although these result in only about 2000–2500 deaths annually, because of their sheer numbers, NMSCs represent about 5% of all Medicare cancer expenditures. Those at risk for skin cancer are fair-skinned individuals who tan poorly and who have had significant chronic or intermittent sun exposure. Red hair phenotype with loss-of-function mutations in the melanocortin-1 receptor may be a risk factor as well. Additional risk factors include a history of skin cancer, prior radiation therapy, PUVA treatment, arsenic exposure, and systemic immunosuppression ( Fig. 29.10 ). Once an individual has developed an NMSC, the risk for a second is increased 10-fold. Over the 3-year period after the initial NMSC diagnosis, more than 40% of BCC and SCC patients develop a BCC, and 18% of SCC patients develop another SCC. By 5 years, as many as 50% of women and 70% of men will develop a second NMSC. The rate of developing NMSCs is no different 3 years or 10 years after the initial NMSC diagnosis. Patients with a history of NMSC should be examined regularly for NMSCs.

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is the major cause of nongenital NMSCs and actinic keratoses. The effect of UVR appears to be mediated through mutation of the p53 gene, which is found mutated in a substantial percentage of NMSCs and actinic keratoses. Most skin cancers are highly immunogenic, but the immune response is suppressed by continued actinic exposure. Both chronic sun exposure and intermittent intense exposure are risk factors for the development of NMSCs. It is believed that avoiding sun exposure reduces the risk for NMSC. The use of sunscreens in the prevention of NMSCs has been controversial; they may inadvertently lead to prolonged intentional sun exposure, negating their possible beneficial effect. Nonetheless, dermatologists and their societies recommend a program of sunscreen use together with sun avoidance to patients at risk for skin cancer. This includes avoiding midday sun, seeking shade, wearing protective clothing, and regularly applying a sunblock of sun protection factor (SPF) 15–30 with both UVB and UVA coverage. This program was pioneered in Australia and has led to improvements in some skin cancer rates there.

Marcil I, Stern RS: Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol 2000; 136: 1524.

Olsen, CM, et al: Turning the tide? Changes in treatment rates for keratinocytic cancers in Australia 2000 through 2011. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 21.

Rogers, HW, et al: Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 283.

Wysong, A, et al: Nonmelanoma skin cancer visits and procedure patterns in a nationally representative sample. Dermatol Surg 2013; 39: 596.

Actinic Keratosis (Solar Keratosis)

Actinic keratoses represent in situ dysplasias resulting from sun exposure. They are found chiefly on the chronically sun-exposed surfaces of the face ( Fig. 29.11 ), ears, balding scalp, dorsal hands, and forearms. They are usually multiple, discrete, flat or elevated, verrucous or keratotic, red, pigmented, or skin colored. Usually, the surface is covered by an adherent scale, but sometimes it is smooth and shiny. On palpation, the surface is rough, like sandpaper, and at times lesions are more easily felt than seen. The patient may complain of tenderness when the lesion is rubbed or shaved over with a razor. The lesions are usually relatively small, measuring 3 mm to 1 cm in diameter, most being less than 6 mm. Rarely, lesions may reach 2 cm in size, but a lesion larger than 6 mm should be considered an actinic keratosis only if confirmed by biopsy or if it completely resolves with therapy. The hypertrophic type, which may lead to cutaneous horn formation, is most frequently present on the dorsal forearms and hands.

Actinic keratoses are the most common epithelial precancerous lesions. Although lesions typically appear in persons over age 50, actinic keratoses may occur in the twenties or thirties in patients who live in areas of high solar irradiation and have fair skin. Patients with actinic keratoses have a propensity for the development of nonmelanoma cutaneous malignancies. Actinic keratoses can be prevented by the regular application of sunscreen and by a low-fat diet. Beta carotene is of no benefit in preventing actinic keratoses.

Six types of actinic keratosis can be recognized histologically: hypertrophic, atrophic, bowenoid, acantholytic, pigmented, and lichenoid. The epidermis may be acanthotic or atrophic. Keratinocyte maturation may be disordered, with overlying parakeratosis sometimes present. The basal cells are most frequently dysplastic, although in more advanced lesions, dysplasia may be seen throughout the epidermis, simulating BD (bowenoid actinic keratosis).

The clinical diagnosis of actinic keratosis is usually straightforward. Early lesions of chronic cutaneous LE, erosive and pustular dermatosis of the scalp, and pemphigus foliaceus are sometimes confused with actinic keratoses. Seborrheic keratoses, even when lacking pigmentation, are usually more “stuck on” in appearance and more sharply marginated than actinic keratoses. Dermoscopy may aid in this distinction. It is difficult to distinguish hypertrophic actinic keratoses from early SCC, and a low threshold for biopsy is recommended. Similarly, actinic keratoses, which present as red patches, cannot easily be distinguished from BD or superficial BCC. If there is a palpable dermal component, or if on stretching the lesion there is a pearly quality, a biopsy should be considered. Any lesion larger than 6 mm, and any lesion that has failed to resolve with appropriate therapy for actinic keratosis, should also be carefully evaluated for biopsy.

Because some percentage of actinic keratoses will progress to NMSC, their treatment is indicated. There are many effective therapeutic modalities. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is most effective and practical when there are a limited number of lesions. A bulky cotton applicator dipped into liquid nitrogen or a handheld nitrogen spray device can be used. If the cotton-tipped applicator method is used, the liquid nitrogen into which the applicator is dipped should be used for only one patient, because there is a theoretic risk of cross-contamination from one patient to another. Infectious agents are not killed by freezing, so many dermatologists now use the spray devices. We recommend using a small-opening tip with continuous bursts of nitrogen spray in a circular motion, depending on the size of the lesion, attempting an even frosting. Only the lesion should be frosted, and the duration of cryotherapy must be carefully controlled. A long freeze that results in significant epidermal-dermal injury produces white scars, which are easily seen on the fair skin of those at risk for actinic keratoses. When correctly performed, healing usually occurs within 1 week on the face, but may require up to 4 weeks on the arms and legs. Caution should be exercised when treating below the knee, because wound healing in these regions is particularly poor, and a chronic ulcer can result. Also, caution is required in persons at risk for having a cryoprotein, such as hepatitis C virus–infected patients and those with connective tissue disease or lymphoid neoplasia, who may have an excessive reaction to cryotherapy. It is better on the first visit to “undertreat” until the tolerance of a patient’s skin to cryotherapy is known. Application of 0.5% 5-FU for 1 week before cryotherapy improves the response.

For extensive, broad, or numerous lesions, topical chemotherapy is recommended. Any lesion that could represent an NMSC should be biopsied before beginning topical chemotherapy or photodynamic therapy (PDT) for actinic keratoses. The two agents most frequently used are 5-FU cream, 0.5%–5%, or imiquimod 5% cream. Topical tretinoin and adapalene do not have the efficacy of these two agents but can be used for prolonged periods and represent an option for patients with a few early lesions. They are also useful for pretreatment of hyperkeratotic lesions before a course of 5-FU. Also, 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel can be effective when used for 60 days for actinic keratoses. Topical resiquimod and ingenol mebutate are newer topical therapeutic options and trichloracetic acid peels may still be useful in some patients. The inflammatory reaction with these agents parallels efficacy, but some data suggest a trend toward less irritation without diminished efficacy if dimethicone lotion is applied before ingenol mebutate.

The frequency and duration of treatment are determined by the individual’s reaction and the anatomic site of application. 5-FU is applied once daily in most cases. For the face, 0.5% 5-FU tends to give a predictable response, which is slightly less severe than that produced by the 1%–5% concentrations. Some patients prefer the stronger concentration for a briefer period, while others favor a slower onset of the reaction and a more prolonged course. For the 5% cream, treatment duration rarely needs to exceed 2–3 weeks. For the 0.5% cream, the treatment course is typically 3–6 weeks. Usually, the central face will respond more briskly than the temples and forehead, which may require a longer duration of treatment. If the reaction is brisk, a midstrength corticosteroid ointment can be helpful or the treatment can be stopped and restarted at a lower concentration. Depending on the individual’s sensitivity, an erythematous burning reaction will occur within several days. Treatment is stopped when a peak response occurs, characterized by a change in color from bright to dusky red, reepithelialization, and crust formation. Healing usually occurs within another 2 weeks of stopping treatment, depending on the treatment site. Certain areas of the face are prone to intense irritant dermatitis when exposed to 5-FU, and tolerance can be improved if the patient avoids application to the glabella, melolabial folds, and chin. For the scalp, the 0.5% concentration may be adequate, but prolonged or multiple treatment courses often are required if this low concentration is used. The 5% cream produces a more predictable, although brisk, reaction. A thick cutaneous horn can prevent penetration of 5-FU, and hypertrophic actinic keratoses on the scalp, dorsal hand, and forearm may respond poorly unless the area is pretreated with an agent to remove excessive keratin overlying the lesions. Pretreatment with tretinoin for 2–3 weeks can improve efficacy and shorten the duration of subsequent 5-FU treatment. It has been observed that 5-FU “seeks out” lesions that may not be clinically apparent. The use of topical 5-FU to the face can also reverse photoaging. Clinically inapparent BCCs may be detected during or on completion of the treatment. Rarely, patients who have had multiple courses of 5-FU topical chemotherapy will develop a true allergic contact dermatitis to the 5-FU. This is manifested by the redness, edema, or vesiculation extending beyond the area of application and by the patient developing pruritus rather than tenderness of the treated areas. Patch testing can be confirmatory.

Imiquimod is an interferon (IFN) inducer and eradicates actinic keratoses by producing a local immunologic reaction against the lesions. The ideal protocol for application of imiquimod may not yet be determined. About 80% of patients respond to imiquimod, and 20% may not respond at all, perhaps because that they lack some genetic component required to induce an inflammatory cascade when imiquimod is applied. If it is applied three times a week, patients develop an inflammatory reaction similar to that seen with daily application of 5-FU. The severity of the reaction is somewhat unpredictable, with a small subset of patients, especially fair-skinned women, developing a severe burning and crusting reaction after only one or a few applications. In others, no reaction at all occurs. With twice-weekly application, the treatment course is prolonged, up to 16 weeks. Severe erythema occurs in 17.7% and scabbing/crusting in 8.4% of patients so treated. The median percentage reduction in actinic keratoses is 83.3% with this treatment protocol. However, only 7% of patients treating actinic keratoses on the arms and hands with imiquimod three times per week achieved complete clearance. Applying it more frequently leads to increased toxicity. Overall, although the reaction is less predictable with imiquimod, it is also typically less severe than with high-concentration 5-FU. The adverse event rates are similar to those with low-concentration (0.5%) 5-FU. Another regimen is to apply imiquimod for long periods at a reduced frequency, once or twice weekly. Applications can be in alternating 1-month cycles or continuous for many months. This may allow management of some patients who require treatment but cannot tolerate any significant changes in appearance. Ultimately, the choice between topical 5-FU and imiquimod will be based on patient preference, prior physician and patient experience with the modalities, and the cost. Imiquimod is significantly more expensive per gram than any form of 5-FU. A meta-analysis comparing efficacy studies of the two agents dosed in various concentrations and regimens suggested imiquimod may have higher efficacy for actinic keratosis on the face and scalp. A recent Cochrane review concluded that 5-FU, imiquimod, ingenol mebutate, and diclofenac are similarly efficacious but have different adverse events and cosmetic outcomes. Direct comparative trials between these agents would be of great value in determining the optimal and most cost-effective strategy for the treatment of extensive actinic keratosis, and the cost of treatment can vary widely depending on the modality chosen.

Surgical management of actinic keratoses with chemical peels, laser resurfacing, and PDT are discussed in Chapters 37 and 38 .

Bower C: Field treatment of actinic keratosis on the scalp. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 1425.

Gupta AK, et al: Interventions for actinic keratoses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD004415.

Hanke CW, et al: Safety and efficacy of escalating doses of ingenol mebutate for field treatment of actinic keratosis on the full face, full balding scalp, or chest. J Drugs Dermatol 2017; 16: 438.

Holzer G, et al: Randomized controlled trial comparing 35% trichloroacetic acid peel and 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for treating multiple actinic keratosis. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 1155.

Jim On S, et al: Regression analysis of local skin reactions to predict clearance of actinic keratosis on the face in patients treated with ingenol mebutate gel. J Drugs Dermatol 2017; 16: 112.

Khanna R, et al: Patient satisfaction and reported outcomes on the management of actinic keratosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017; 10: 179.

Kirby JS, et al: Variation in the cost of managing actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 264.

Micali G, et al: Topical pharmacotherapy for skin cancer. Part II. Clinical applications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 979.e1.

Tolley K, et al: Pharmacoeconomic evaluations in the treatment of actinic keratoses. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2017; 30: 178.

Walker JL, et al: 5-Fluorouracil for actinic keratosis treatment and chemoprevention. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 1367.

Cutaneous Horn (Cornu Cutaneum)

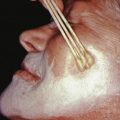

Cutaneous horns are encountered most frequently on the dorsal hands and scalp. Lesions may also occur on the hands, penis, ears ( Fig. 29.12 ), and eyelids. They are skin-colored, horny excrescences 2–60 mm long, sometimes divided into several antler-like projections.

These lesions are most often benign, with the hyperkeratosis being superimposed on an underlying seborrheic keratosis, verruca vulgaris, angiokeratoma, molluscum contagiosum, or trichilemmoma in about 60% of cases. However, 20%–30% may overlie premalignant keratosis, and 20% may overlie SCCs or BCCs. The risk for a cutaneous horn overlying a malignancy is much higher in fair-complexioned elderly persons. Hyperkeratotic actinic plaques less than 1 cm in diameter on the dorsum of the hand, wrist, or forearms in white patients have been shown to have a malignancy rate of 50%. One third of penile horns are associated with underlying malignancies. Excisional biopsy with histologic examination of the base is necessary to determine the best therapy, which would be dictated by the diagnosis of the underlying lesion and by the apparent adequacy of removal.

Mantese SA, et al: Cutaneous horn. An Bras Dermatol 2010; 85: 157.

Keratoacanthoma

Clinical Features

There are four types of keratoacanthoma: solitary, multiple, eruptive, and keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum. The exact biologic behavior of keratoacanthoma remains controversial. In the past, it had been considered a reactive condition or pseudomalignancy that could be treated expectantly. Now, the favored view is that keratoacanthomas are low-grade SCCs, which in many cases will regress. The regression may be partially mediated by immunity but takes the form of terminal differentiation. The course of these tumors is unpredictable. Even those that ultimately involute can cause considerable destruction before they regress. Any lesions that have the histologic features of keratoacanthoma and appear in an immunosuppressed host should be managed as an SCC, with complete eradication.

Sunlight appears to play an important role in the etiology, especially in the solitary types, with light-skinned persons being predominantly affected. Cases of keratoacanthoma after trauma, hypertrophic lichen planus, discoid LE, tattoos, fractional thermolysis, and imiquimod erosions, and along the distal ends of surgical excisions, suggest that an isomorphic phenomenon is common. The keratoacanthomas appear about 1 month after the traumatic injury. All these associated conditions result in damage to the dermis, especially along the DEJ, and necessitate wound healing. The biologic behavior of these lesions is unknown, but they have added to the controversy of keratoacanthoma as a reactive versus a malignant process. Eruptive keratoacanthomas and SCCs have appeared during treatment for metastatic melanoma with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib as well as with anti-PD1 agents such as pembrolizumab. In Muir-Torre syndrome, sebaceous tumors and keratoacanthomas occur in association with multiple internal malignancies. A second, less common cancer scenario is the keratoacanthoma–visceral carcinoma syndrome (KAVCS); only a handful of cases have been reported. Patients have multiple or large keratoacanthomas that appear at the same time as an internal malignancy, always of the genitourinary tract. The relationship of Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS) to KAVCS awaits identification of the genetic basis of both syndromes.

Solitary Keratoacanthoma

The solitary keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing papule that enlarges from a 1-mm macule or papule to as large as 25 mm in 3–8 weeks. When fully developed, it is a hemispheric, dome-shaped, skin-colored nodule that has a smooth crater filled with a central keratin plug ( Fig. 29.13 ). The smooth shiny lesion is sharply demarcated from its surroundings. Telangiectases may run through the lesion. Subungual keratoacanthomas are tender subungual tumors that usually cause significant nail dystrophy. Subungual lesions often do not regress spontaneously and induce early underlying bony destruction, characterized on radiograph as a crescent-shaped lytic defect without accompanying sclerosis or periosteal reaction.

The solitary keratoacanthoma occurs mostly on sun-exposed skin, with the central portion of the face, backs of the hands, and arms most often involved. Less frequently, other sites are involved, such as the buttocks, thighs, penis, ears, and scalp. Elderly fair-skinned individuals most frequently develop keratoacanthomas. Lesions of the dorsal hands are more common in men, and keratoacanthomas of the lower legs are more common in women. The most interesting feature of this disease is the rapid growth for 2–6 weeks, followed by a stationary period for another 2–6 weeks, and finally a spontaneous involution over another 2–6 weeks, leaving a slightly depressed scar. The stationary period and involuting phase are variable; some lesions may take 6 months to 1 year to resolve completely. An estimated 5% of treated lesions recur. Invasion along nerve trunks has been documented and may result in recurrence after a seemingly adequate excision.

Histopathology

The histologic findings of keratoacanthoma and a low-grade SCC are so similar that it is frequently difficult to make a definite diagnosis on the histologic findings alone. When a properly sectioned specimen is examined under low magnification, the center of the lesion shows a crater filled with eosinophilic keratin. Over the sides of the crater, which seems to have been formed by invagination of the epidermis, a “lip” or “marginal buttress” of epithelium extends over the keratin-filled crater. At the base and sides of the crater, the epithelium is acanthotic and composed of keratinocytes, which are highly keratinized and have an eosinophilic, glassy cytoplasm. Surrounding the keratinocyte proliferation, a dense inflammatory infiltrate is frequently seen. Neutrophilic microabscesses are common within the tumor, and trapping of elastic fibers is often identified at the periphery of the tumor. These features favor a diagnosis of keratoacanthoma. The most definitive histologic feature is evidence of terminal differentiation, where the scalloped outer border of the tumor has lost its infiltrative character and is reduced to a thin rim of keratinizing cells lining a large, keratin-filled crater. The presence of acantholysis within the tumor is incompatible with a diagnosis of keratoacanthoma. It is also important to distinguish keratoacanthoma from marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in prurigo nodularis. Unfortunately, histology does not completely correlate with biologic behavior. The diagnosis of benign-behaving keratoacanthoma versus a potentially aggressive SCC may not always be possible. Even if the classic histologic features of keratoacanthoma are seen, the diagnosis of SCC should be considered if the lesion does not behave as expected.

Treatment

Although keratoacanthomas spontaneously involute, it is impossible to predict how long this will take. The patient may be faced with destructive growth of a tumor for as long as 1 year. More importantly, SCC cannot always be excluded clinically. Therefore excisional biopsy of the typical keratoacanthoma of less than 2 cm in diameter should be considered in most cases. If the history is characteristic, or multiple lesions have appeared simultaneously, less aggressive interventions may be considered. Nonsurgical therapy may also be considered in certain sites to preserve function or improve cosmetic outcome.

Intralesional injections of 5-FU solution, 50 mg/mL (undiluted from ampule) at weekly intervals; bleomycin, 0.5 mg/mL; or methotrexate, 25 mg/mL, can be effective. For a typical lesion, four injections along the base at each pole are recommended. Low-dose systemic methotrexate can be considered if multiple lesions are present and there is no contraindication. For clinically typical lesions, these modalities may be tried before resorting to surgical removal, especially if the latter presents any problem. Excision is recommended if there is not at least 50% involution of the lesion after 3 weeks. Radiation therapy may also be used on giant keratoacanthomas when surgical excision or electrosurgical methods are not feasible.

Eruptive Keratoacanthomas of the Lower Leg

In older patients, especially older women, keratoacanthomas on the lower legs are often multiple and erupt in great numbers when one is treated surgically. The old quip is that “you kill one and five come to the funeral.” An effective approach is to treat the lesions with 5-FU cream under Unna boot occlusion. Topical imiquimod, intralesional 5-FU, intralesional methotrexate, psoriatic doses of oral methotrexate, and oral acitretin can also be useful.

Multiple Keratoacanthomas (Ferguson Smith Type)

This type of keratoacanthoma is frequently referred to as the Ferguson Smith type of multiple self-healing keratoacanthoma. These lesions are identical clinically and histologically to the solitary type. There is frequently a family history of similar lesions. The condition has been traced to two large Scottish kindreds. Affected families from other countries have also been reported. Beginning on average at about age 25, but possibly as early as the second decade, patients develop crops of keratoacanthomas that begin as small red macules and rapidly become papules that evolve to typical keratoacanthomas. Lesions may number from a few to hundreds, but generally only 3–10 lesions are noted at any one time. Sun-exposed sites are favored, especially the ears and nose, and in most cases scalp lesions occur. In addition, these patients typically develop keratoacanthomas at sites of trauma, often at the ends of surgical excisions. Lesions grow over 2–4 weeks, reaching a size of 2–3 cm, then remain stable for 1–2 months before slowly involuting. They leave a prominent crateriform scar. If the early lesions are aggressively treated with cryotherapy, shave removal, or curettage, the scar may be less marked than that induced by spontaneous involution. Treatment with an oral retinoid can be effective in stopping the appearance of new lesions and causing involution of existing ones.

Generalized Eruptive Keratoacanthomas (Grzybowski Variant)

The generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma is very rare and sporadic, with most patients having no affected family members. The usual age of onset is between 40 and 60. The patients are usually in good health and are not immunosuppressed. The cause of this condition is unknown. HPV has not been detected in most patients in whom it was sought. The clinical features are characteristic and unique. The Grzybowski type of multiple keratoacanthoma is characterized by a generalized eruption of numerous dome-shaped, skin-colored papules 2–7 mm in diameter. Multiple larger typical keratoacanthomas may also appear. Thousands of lesions may develop. The eruption is usually generalized, but spares the palms and soles. The oral mucous membranes and larynx can be involved. Severe pruritus may be a feature. Clinically, pityriasis rubra pilaris or widespread lichen planopilaris are often considered. Bilateral ectropion, narrowing of the oral aperture, and severe facial disfigurement can result. Linear arrangement of some lesions, especially over the shoulders and arms, has also been noted. Despite the multiplicity of lesions, no case of “metastasis” from a skin lesion or increased risk of internal malignancy has been reported in the Grzybowski variant of keratoacanthoma. Dr. Grzybowski’s original patient died of a myocardial infarction 16 years after diagnosis. Oral treatment with retinoids, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide can prove effective.

Keratoacanthoma Centrifugum Marginatum

This uncommon variant of keratoacanthoma is usually solitary, although multiple lesions can occur. Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum is characterized by progressive peripheral expansion and concomitant central healing, leaving atrophy. Spontaneous involution, as may be seen in other variants of keratoacanthoma, does not occur. Lesions range from 5–30 cm in diameter ( Fig. 29.14 ). The dorsum of the hands and pretibial regions are favored sites. Oral treatment with etretinate and methotrexate with prednisone has been effective in isolated cases.

Annest NM, et al: Intralesional methotrexate treatment for keratoacanthoma tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 989.

Anzalone CL, Cohen PR: Generalized eruptive keratoacanthomas of Grzybowski. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53: 131.

Baykal C, et al: Management of keratoacanthoma in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016; 30: e91.

Bieber AK, et al: Systemic methotrexate for prurigo nodularis and keratoacanthomas in actinically damaged skin. JAAD Case Rep 2016; 2: 269.

Hawilo A, et al: Keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum. Skinmed 2017; 15: 69.

John AM, et al: Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 558.

Kwiek B, et al: Keratoacanthoma (KA). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 1220.

Ogita A, et al: Histopathological diagnosis of epithelial crateriform tumors. J Dermatol 2016; 43: 1321.

Rhee do Y, et al: Successful treatment of multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas by topical application of imiquimod cream. J Dermatolog Treat 2016; 27: 448.

Takai T: Advances in histopathological diagnosis of keratoacanthoma. J Dermatol 2017; 44: 304.

Veerula VL, et al: Multiple keratoacanthomas occurring in surgical margins and de novo treated with intralesional methotrexate. Cutis 2016; 98: E12.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and many other countries with a largely white, fair-skinned population with moderate sun exposure. In Hawaii, the incidence of BCC is 14-fold higher in persons of European ancestry (especially Celtic) than in Japanese, and 34-fold higher than in Filipinos. Still, persons of color can develop BCCs, especially fair-skinned Asians and Hispanics who have accumulated significant lifetime sun exposure from occupational sources, usually farm work. White Hispanics have less skin cancer awareness, use sun protection less frequently, and are more likely to use tanning beds than darker-skinned Hispanics. They represent a prevalent at-risk population for skin cancer over the next decades.

Intermittent intense sun exposure, as identified by prior sunburns; radiation therapy; a positive family history of BCC; immunosuppression; a fair complexion, especially red hair; easy sunburning (skin types I or II); and blistering sunburns in childhood are risk factors for the development of BCC. Indoor tanning is a strong risk factor for early-onset BCC, particularly among women. Of interest, actinic elastosis and wrinkling are not risk factors for the development of BCC. In fact, BCCs are relatively rare on the dorsal hand, where sun exposure is high, whereas actinic keratoses and SCCs abound. SCC is three times more common than BCC on the dorsum of the hand. These findings suggest that the mechanism by which UVR induces BCC is not related solely to the total amount of UVR received. In contrast to actinic keratoses and SCCs, prevention with regular use of sunscreens is more difficult to demonstrate. The ratio of BCC to SCC decreases as one moves from northern (≈10) to southern (≈2) United States. Once a person has had a BCC, his or her risk for a subsequent BCC is high: 44% in the next 3 years.

Many clinical morphologies of BCC exist. Clinical diagnosis depends on the clinician being aware of the many forms BCC may take. Because these clinical types may also have different biologic behavior, histologic classification of the type of BCC may also influence the therapy chosen.

Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma (Classic Basal Cell Carcinoma)

The classic or nodular BCC constitutes 50%–80% of all BCCs. Nodular BCC is composed of one or a few small, waxy, semitranslucent nodules forming around a central depression that may or may not be ulcerated, crusted, and bleeding. The edge of larger lesions has a characteristic rolled border. Telangiectases course through the lesion. Bleeding on slight injury is a common sign. As growth progresses, crusting appears over a central erosion or ulcer, and when the crust is knocked or picked off, bleeding occurs, and the ulcer becomes apparent. This ulcer is characterized by chronicity and gradual enlargement over time. The lesions are asymptomatic, and bleeding is the only difficulty encountered. The lesions are most frequently found on the face ( Fig. 29.15 ) (85%–90% on head and neck) and especially on the nose (25%–30%). The forehead, ears, periocular areas, and cheeks are also favored sites. However, any part of the body may be involved.

Cystic Basal Cell Carcinoma

These dome-shaped, blue-gray cystic nodules are clinically similar to eccrine and apocrine hidrocystomas.

Morpheaform, or Cicatricial Basal Cell Carcinoma

This type of BCC presents as a white sclerotic plaque, and 95% of these occur on the head and neck. Ulceration, a pearly rolled border, and crusting are usually absent. Telangiectasia is variably present. Therefore the lesion is often missed or misdiagnosed for some time. The differential diagnosis includes desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, a scar, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and desmoplastic melanoma. The unique histologic feature is the strands of basal cells interspersed amid densely packed, hypocellular connective tissue. Morpheic BCCs constitute 2%–6% of all BCCs. Data suggest use of fluorouracil may be a risk factor for morpheaform versus nonmorpheaform BCC.

Infiltrative Basal Cell Carcinoma

Infiltrative BCC is an aggressive subtype characterized by deep infiltration of spiky islands of basaloid epithelium in a fibroblast-rich stroma. Clinically, it lacks the scarlike appearance of morpheiform BCC. Histologically, the stroma is hypercellular, the islands are jagged in outline, and squamous differentiation is common.

Micronodular Basal Cell Carcinoma

These tumors are not clinically distinctive, but the micronodular growth pattern makes them less amenable to curettage.

Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma

Superficial BCC is also termed superficial multicentric BCC. This is a common form of BCC, comprising at least 15% of the total. It favors the trunk (45%) or distal extremities (14%). Only 40% occur on the head and neck. The multicentricity is merely a histologic illusion created by the passing of the plane of section through the branches of a single, multiply branching lesion.

This type of BCC most frequently presents as a dry, psoriasiform, scaly lesion. It is usually a superficial flat growth, which in many cases exhibits little tendency to invade or ulcerate. The lesions enlarge very slowly and may be misdiagnosed as patches of eczema or psoriasis. They may grow to be 10–15 cm in diameter. Close examination of the edges of the lesion will show a threadlike raised border ( Fig. 29.16 ). These erythematous plaques with telangiectasia may occasionally show atrophy or scarring. Some lesions may develop an infiltrative component in their deeper aspect and grow into the deeper dermis. When this occurs, they may induce dermal fibrosis and multifocal ulceration, forming a “field of fire” type of large BCC. Sometimes the lesion will heal at one place with a white atrophic scar and then spread actively to the neighboring skin. A patient can have several of these lesions simultaneously or over time. This form of BCC is the most common pattern seen in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and BCC.

Pigmented Basal Cell Carcinoma

This variety has all the features of nodular BCC, but in addition, brown or black pigmentation is present ( Fig. 29.17 ). When dark-complexioned persons, such as Latin Americans, Hispanics, or Asians, develop BCC, this is the type they tend to develop. Pigmented BCCs make up 6% of all BCCs. In the management of these lesions, it should be known that, if ionizing radiation therapy is chosen, the pigmentation remains at the site of the lesion.

Rodent Ulcer

Also known as Jacobi ulcer, rodent ulcer is a neglected BCC that has formed an ulceration. The pearly border of the lesion may not be recognized. If it occurs on the lower extremity, it may be misdiagnosed as a vascular ulceration.

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

First described by Pinkus as premalignant fibroepithelial tumor, this is usually an elevated, skin-colored, sessile lesion on the lower trunk, lumbosacral area, groin, or thigh and may be as large as 7 cm. The lesion is superficial and resembles a fibroma or papilloma. Histologically, interlacing basocellular sheets extend downward from the surface to form an epithelial meshwork enclosing a hyperplastic mesodermal stroma. As with infundibulocystic BCC, fibroepithelioma is composed of pink epithelial strands with blue basaloid buds. Fibroepithelioma has a more prominent fibromucinous stroma and lacks the horn cysts characteristic of infundibulocystic BCC. Fibroepithelioma often demonstrates sweat ducts within the pink epithelial strands. A slight inflammatory infiltrate may also be present. Simple removal by excision or electrosurgery is the treatment of choice.

Polypoid Basal Cell Carcinoma

The polypoid BCCs present as exophytic nodules of the head and neck.

Porelike Basal Cell Carcinoma