Lesions on the mucous membranes may be more difficult to diagnose than lesions on the skin, and not merely because they are less easily and less often seen. There is less contrast of color and greater likelihood of alterations in the original appearance because of secondary factors, such as maceration from moisture, abrasion from food and teeth, and infection. Vesicles and bullae rapidly rupture to form grayish erosions, and the epithelium covering papules becomes a soggy, lactescent membrane, easily rubbed off to form an erosion. Grouping and distribution are less distinctive in the mouth than on the skin, and in some cases it is necessary to establish the diagnosis by observing the character of any associated cutaneous lesions or by noting subsequent developments.

Cheilitis

Cheilitis Exfoliativa

The term cheilitis exfoliativa has been used to designate a primarily desquamative, mildly inflammatory condition of the lips, of unknown cause, and also a clinically similar reaction secondary to other disease states. The former is a persistently recurring lesion that produces scaling and sometimes crusting; it most often affects the upper lip. The recurrent exfoliation leaves a temporarily erythematous and tender surface.

In the latter form, the lips are chronically inflamed and covered with crusts that from time to time tend to desquamate, leaving a glazed surface on which new crusts form. Fissures may be present, and there may be burning, tenderness, and some pain. The lower lip is more often involved, with the inflammation limited to the vermilion part. The cheilitis may be secondary to seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, retinoid therapy, pyorrhea, long-term actinic exposure, or the habit of lip licking. Infrequently, the initial or only manifestation of AD may be a chronic cheilitis. Irritating or allergenic substances in lipsticks, dentifrices, and mouthwashes may be causative factors. Dyes in lipsticks may photosensitize. Candidiasis may be present. Cheilitis may be part of Plummer-Vinson or Sjögren syndrome. Cheilitis is seen in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and it is a known common complication of protease inhibitor therapy. These and other, uncommon causes of cheilitis are discussed in more detail within the specific entities.

The only uniformly effective treatment of cheilitis exfoliativa is the elimination of causes when they can be found. Topical tacrolimus ointment, pimecrolimus cream, or low-strength corticosteroid ointments and creams are usually helpful. Excimer laser therapy or the handheld ultraviolet B (UVB) unit may be useful. If the underlying etiology is determined, specific therapy may be instituted. When there are fissures, petrolatum or zinc oxide ointment applied liberally and often may heal them.

Almazrooa SA, et al: Characterization and management of exfoliative cheilitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2013; 116: e485.

Bhatia BK, et al: Excimer laser therapy and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy for exfoliative cheilitis. Int J Womens Dermatol 2015; 1: 95.

Allergic Contact Cheilitis

The vermilion border of the lips is much more likely to develop allergic contact sensitivity reactions than is the oral mucosa. Allergic cheilitis is characterized by dryness, fissuring, edema, crusting, and angular cheilitis. Over 90% of patients are women and over half of the reactions are caused by lipsticks. Although patch testing with standard allergens will reveal a relevant positive in approximately 25%–30% of patients, about one in five will only react to their own product. It may result from use of topical medications ( Fig. 34.1 ), dentifrices and other dental preparations, antichap agents, lipsticks, and sunscreen-containing lip balms; from contact with cosmetics, nail polish, rubber, and metals; or from eating foods such as mangoes. Fragrance and nickel are the most commonly identified individual sensitizers.

Treatment includes discontinuation of exposure to the offending agent and administration of topical tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, or corticosteroid preparations.

Aerts O, et al: Contact dermatitis caused by pharmaceutical ointments containing “ozonated” olive oil. Contact Dermatitis 2016; 75: 123.

Alrowaishdi F, et al: Allergic contact cheilitis caused by carnauba wax in a lip balm. Contact Dermatitis 2013; 69: 311.

Barrientos N, et al: Contact cheilitis caused by candelilla wax contained in lipstick. Contact Dermatitis 2013; 69: 126.

Bourgeois P, Goossens A: Allergic contact cheilitis caused by menthol in toothpaste and throat medication. Contact Dermatitis 2016; 75: 113.

Budimir V, et al: Allergic contact cheilitis and perioral dermatitis caused by propolis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2012; 20: 187.

de Groot A: Contact allergy to (ingredients of) toothpastes. Dermatitis 2017; 28: 95.

O’Gorman S, Torgerson RR: Contact allergy in cheilitis. Int J Dermatol 2016; 55: e386.

Panasoff J: Cheilitis caused by to mint-containing toothpastes. Contact Dermatitis 2016; 75: 260.

Sarre ME, et al: Allergic contact cheilitis caused by polysilicone-15 (Parsol SLX) in a lip care balm. Contact Dermatitis 2014; 70: 119.

Tan S, et al: Allergic contact dermatitis to Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru) in papaw ointment causing cheilitis. Australas J Dermatol 2011; 52: 222.

Actinic Cheilitis

Actinic cheilitis is an inflammatory reaction of the lips to chronic excessive sunlight exposure over many years. The lower lip, which is usually the only one involved, becomes scaly, fissured, atrophic ( Fig. 34.2 ), and at times eroded and swollen; leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may develop. Painful erosions may occur; actual ulceration is very rare unless carcinoma has developed. Hereditary polymorphous light eruption can resemble chronic actinic cheilitis, but it has no malignant potential.

Avoiding sun exposure and the use of sunscreen containing lip pomades suffice to minimize further damage. A biopsy should be performed on any suspicious, thickened areas that persist; preferably, a shave technique should be used to avoid scarring.

Cryosurgical treatment may be effective, particularly for localized lesions. In cases with diffuse involvement, application of topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, ingenol, or photodynamic therapy (PDT) may be curative. Treatment with a thulium fractionated or ablative erbium laser, dermabrasion, or electrodesiccation may be required for severe disease and provides excellent results. Long-term follow-up is necessary. Should treatment fail, vermilionectomy of the lower lip may be necessary. Excision of the exposed vermilion mucous membrane with advancement of the labial mucosa to the skin edge of the outer lip is effective, but this is performed less frequently since the advent of laser therapy. Refer to Chapter 29 for more information on actinic cheilitis.

Cohen JL: Erbium laser resurfacing for actinic cheilitis. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12: 1290.

Dufresne RG Jr, et al: Dermabrasion for actinic cheilitis. Dermatol Surg 2008; 34: 848.

Flórez Á, et al: Management of actinic cheilitis using ingenol mebutate gel. J Dermatolog Treat 2017; 28: 149.

Ghasri P, et al: Treatment of actinic cheilitis using a 1,927-nm thulium fractional laser. Dermatol Surg 2012; 38: 504.

Muthukrishnan A, Bijai Kumar L: Actinic cheilosis. BMJ Case Rep 2017 Mar 20; 2017.

Vieira RA, et al: Actinic cheilitis and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip. An Bras Dermatol 2012; 87: 105.

Yazdani Abyaneh MA, et al: Photodynamic therapy for actinic cheilitis. Dermatol Surg 2015; 41: 189.

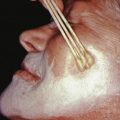

Cheilitis Glandularis

Cheilitis glandularis is characterized by swelling and eversion of the lower lip, patulous openings of the ducts of the mucous glands, cysts, and at times, abscess formation. There is general enlargement of the lips ( Fig. 34.3 ). Mucus exudes freely to form a gluey film that dries over the lips and causes them to stick together during the night. When the lip is palpated between the thumb and index finger, the enlarged mucous glands feel like pebbles beneath the surface. The lower lip is the site of predilection. Middle-aged men are most often affected. Cheilitis glandularis is a chronic inflammatory reaction that is caused by an exuberant response to chronic irritation, or to atopic, factitious, or actinic damage.

On biopsy, there is a moderate histiocytic, lymphocytic, and plasmacytic infiltration in and around the glands. Cheilitis glandularis has been reported to eventuate in SCC, but these cases may be attributed to chronic sun exposure, which frequently precedes cheilitis glandularis.

Treatment depends on the nature of the antecedent irritation; in most cases, treatment as described for actinic cheilitis is appropriate. Surgical debulking may be necessary. Intralesional triamcinolone may be beneficial in some patients, as may the combination of minocycline and tacrolimus ointment.

Kumar P, Mandal RK: Cheilitis glandularis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015; 81: 430.

Nico MM, et al: Cheilitis glandularis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 62: 233.

Angular Cheilitis

Angular cheilitis is synonymous with perlèche. Fissures radiate downward and outward from the labial commissures. It is an intertriginous dermatitis caused by excessive wetness or dryness. It is often complicated by secondary infection with Candida albicans or Staphylococcus aureus.

The disease usually occurs in elderly people who wear dentures, but it may develop simply from an overhanging of the upper lip and cheek, and recession and atrophy of the alveolar ridges in old age. Measuring the facial dimensions with a ruler and tongue blade will help with objective assessment of the importance of decreased vertical facial dimension in the development of perlèche. If the distance from the base of the nose to the lower edge of the mandible is greater than or equal to 6 mm less than the distance from the center of the pupil to the parting line of the lips, the vertical dimension is decreased. In these circumstances, drooling is usually a factor. In children, angular cheilitis occurs frequently in thumb suckers, gum chewers, and lollipop eaters. Other inciting factors include riboflavin deficiency, anorexia nervosa, Down syndrome, intraoral candidiasis, especially in patients with diabetes, AIDS, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, Sjögren syndrome, orthodontic treatment, drug-induced xerostomia, and AD.

Opening the “bite” by improving denture fit, capping teeth, replacing lost teeth, or increasing denture height, combined with topical use of nystatin and iodochlorhydroxyquin in hydrocortisone ointment, is usually effective when the condition is associated with anatomically predisposing factors. Stubborn cases typically respond to a slightly stronger corticosteroid, such as desonide, in combination with a topical anticandidal agent. Injection of collagen or insertion of Softform implants to obliterate the angular creases may be beneficial. Therapy for underlying diseases should be maximized. If S. aureus is present, mupirocin ointment may be needed. Excision of the region, followed by a rotating flap graft, is another therapeutic option, but surgery should be reserved for resistant cases.

Adedigba MA, et al: Patterns of oral manifestations of HIV/AIDS among 225 Nigerian patients. Oral Dis 2008; 14: 341.

Lu DP: Prosthodontic management of angular cheilitis and persistent drooling. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2007; 28: 572.

Park KK, et al: Angular cheilitis. Part 1. Cutis 2011; 87: 289.

Park KK, et al: Angular cheilitis. Part 2. Cutis 2011; 88: 27.

Sharifzadeh A, et al: Oral microflora and their relation to risk factors in HIV+ patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. J Mycol Med 2013; 23: 105.

Sharon V, et al: Oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis. Dermatol Ther 2010; 23: 230.

Plasma Cell Cheilitis

This is also referred to as plasma cell orificial mucositis or, when the gingival is the site of involvement, plasma cell gingivitis. It is characterized by a sharply outlined, infiltrated, dark red plaque with a lacquer-like glazing of the surface of the involved area. This lesion has the same microscopic features as Zoon balanitis plasmacellularis. There is plasma cell infiltration in a bandlike pattern. Plasma cell cheilitis is not a response that is specific for any stimulus but rather represents a reaction pattern to any one of a variety of stimuli. Successful therapies include application of topical tacrolimus ointment or clobetasol propionate ointment twice daily, or use of the 308 nm excimer light.

Plasmoacanthoma

Plasma cell cheilitis and plasmoacanthoma have been reported in the same patient and are believed to represent a spectrum of the same disease. Plasmoacanthoma is a verrucous tumor with a plasma cell infiltrate involving the oral mucosa, particularly along the angles. Other locations may occur, such as the perianal, periumbilical, or inguinal areas and toe webs. C. albicans has been found within the tissue, suggesting that it may be implicated as a cause of this disease. Excision, destruction, anticandidal preparations, and intralesional steroids are all options for treatment.

Abhishek K, Rashmi J: Plasma cell gingivitis associated with inflammatory cheilitis. Ethiop J Health Sci 2013; 23: 183.

da Cunha Filho RR, et al: “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J 2014; 20.

Senol M, et al: Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47: 265.

Yoshimura K, et al: Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol 2013; 40: 471.

Drug-Induced Ulcer of the Lip

Painful or tender, well-defined ulcerations without induration on the lower lip may heal after withdrawal of oral medications. The causative drugs may be phenylbutazone, chlorpromazine, phenobarbital, methyldopa, or thiazide diuretics. Solar exposure appears to be a predisposing causative influence; in some cases, this reaction may represent a fixed drug photoeruption. On rare occasions, fixed drug eruptions may also involve the lip, usually caused by naproxen, one of the oxicams, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ( Fig. 34.4 ).

Abdollahi M, et al: A review of drug-induced oral reactions. J Contemp Dent Pract 2003; 4: 10.

Pemberton MN, et al: Fixed drug eruption to oxybutynin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 106: e19.

Other Forms of Cheilitis

Several diseases discussed elsewhere may affect the lips, including lichen planus, lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme, AD, and psoriasis. A high percentage of patients with Down syndrome have cheilitis of one or both lips. Lip biting may be a factor.

Oral and Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease is a chronic granulomatous disease of any part or parts of the bowel. Patients with Crohn disease may develop inflammatory hyperplasia of the oral mucosa, with metallic dysgeusia and gingival bleeding. Reported typical changes include diffuse oral swelling, focal mucosal hypertrophy and fissuring (cobblestoning), persistent ulceration, polypoid lesions, indurated fissuring of the lower lip, angular cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, or pyostomatitis vegetans. Oral involvement occurs in 10%–20% of patients with Crohn disease, and 90% have granulomas on biopsy. Males with early-onset disease are most often affected. Concomitant involvement of the anal and esophageal mucosa is common. Direct extension to perianal skin may occur.

Many cases of Crohn disease with other cutaneous manifestations have been reported, notably pyoderma gangrenosum (more closely associated with ulcerative colitis) and erythema nodosum, Sweet syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, pellagra, pernicious anemia, an acrodermatitis-like eruption, urticaria, and necrotizing vasculitis.

Metastatic Crohn disease denotes noncaseating granulomatous skin lesions in patients with Crohn disease. In the absence of bowel involvement, the diagnosis cannot be made. The morphologic appearances seen include genital swelling or condyloma-like lesions, leg ulceration, pyogenic granuloma–like lesions of the retroauricular skin, and erythematous nodules, plaques, or ulcers in other locations. At times step sectioning or multiple biopsies may be necessary to reveal the granulomas.

Treatment of the gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations with sulfasalazine, metronidazole, systemic corticosteroids, infliximab or other anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, or immunosuppressive medications such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate can improve the cutaneous findings. Several delivery systems use only the active ingredient of sulfasalazine, mesalamine, including Asacol, Pentasa, Rowasa, and olsalazine, and may be useful in treating the skin involvement of Crohn disease. A mouthwash containing triamcinolone acetonide, tetracycline, and lidocaine may provide symptomatic and objective improvement. Cutaneous ulcerated granulomas and erythematous plaques caused by Crohn disease may respond to high-potency topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus ointment. Curettage and zinc by mouth have resulted in healing in several reported patients. Dietary manipulation is another measure that can be helpful in select individuals. The course is often prolonged over several years.

Alemanno G, et al: Rare cutaneous manifestations associated with Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29: 765.

Kurtzman DJ, et al: Metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 804.

Laftah Z, et al: Vulval Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2015; 9: 318.

Marzano AV, et al: Cutaneous manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 213.

Shah NP, et al: Treatment of a Crohn’s disease-related facial lesion with topical tacrolimus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014; 118: e71.

Thrash B, et al: Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68: 211.

Yuksel I, et al: Mucocutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 546.

Pyostomatitis Vegetans

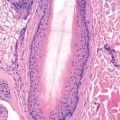

Pyostomatitis vegetans, an inflammatory stomatitis, is most often seen in association with ulcerative colitis but may also occur in other inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn disease. Edema and erythema with deep folding of the buccal mucosa characterize pyostomatitis vegetans, together with pustules, small vegetating projections, erosions, ulcers, and fibrinopurulent exudates ( Fig. 34.5 ). Eroded pustules fuse into shallow ulcers, resulting in characteristic “snail-track” ulcers. It has also been associated with sclerosing cholangitis. Several cases have been reported with no underlying systemic disorder. At times, crusted erythematous papulopustules that coalesce into asymmetric annular plaques may occur with or after the oral lesions. These associated skin lesions favor the axillae, groin, and scalp and are termed pyodermatitis vegetans. Topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus ointment may be effective; systemic corticosteroids or infliximab, however, are usually necessary.

Histologically, there are dense aggregates of neutrophils and eosinophils.

Clark LG, et al: Pyostomatitis vegetans (PSV)–pyodermatitis vegetans (PDV). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 578.

Crippa R, et al: Oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases in children. Part 2. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2016; 17: 164.

Dupuis EC, et al: Pyoblepharitis vegetans in association with pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. J Cutan Med Surg 2016; 20: 163.

Fantus SA, et al: Vegetating plaques on the lips. Am J Dermatopathol 2015; 37: 699.

Muhvic-Urek M, et al: Oral pathology in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 5655.

Wu YH, et al: Pyostomatitis vegetans. J Formos Med Assoc 2015; 114: 672.

Cheilitis Granulomatosa

Cheilitis granulomatosa is characterized by a sudden onset and progressive course, terminating in chronic enlargement of the lips. Usually, the upper lip becomes swollen first; several months may elapse before the lower lip becomes swollen. Usually, only enlargement is present, without ulceration, fissuring, or scaling. The swelling remains permanently. It may be a part of the Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome when associated with facial paralysis and plicated tongue.

The cause is unknown. Histologically, cheilitis granulomatosa is characterized by an inflammatory reaction of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells and by tuberculoid granulomas consisting of epithelioid and Langerhans giant cells. At times, intralymphatic granulomas are found and may account for the clinical swelling. In the differential diagnosis, solid edema, angioedema, cheilitis glandularis, sarcoidosis, oral Crohn disease, lymphangioma, hemangioma, and neurofibroma, infectious granulomas, contact allergy, reaction to silicone fillers, and Ascher syndrome must be considered. Ascher syndrome consists of swelling of the lips with edema of the eyelids (blepharochalasis) and is inherited.

Cheilitis granulomatosa may be the presenting sign in a patient who will develop Crohn disease or sarcoidosis at a later time.

Treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids is usually successful but temporary. Combining this modality with oral antiinflammatory agents for long-term control, such as doxycycline, dapsone, colchicine, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, anti-TNF agents, or topical tacrolimus ointment, is an excellent strategy. In the firmly established case, surgical repair of the involved lip through a mucosal approach and, in some cases, concomitant intralesional corticosteroid treatment provide the best results.

Alvarez-Garrido H, et al: Crohn’s disease and cheilitis granulomatosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 239.

Gonzalez-Garcia C, et al: Intralymphatic granulomas as a pathogenic factor in cheilitis granulomatosa/Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33: 594.

Lynde CB, et al: Cheilitis granulomatosa treated with intralesional corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: e101.

Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome

Melkersson in 1928 and Rosenthal in 1930 described a triad consisting of recurring facial paralysis or paresis, soft nonpitting edema of the lips, and scrotal tongue. Attacks usually start during adolescence, with permanent or transitory paralysis of one or both facial nerves, repeated migraines, and recurring edema of the upper lip, cheeks, and occasionally the lower lip and circumoral tissues. Swelling of the skin and mucous membranes of the face and mouth is the dominant finding and most important diagnostic feature ( Fig. 34.6 ). In order of frequency, the swelling occurs first on the upper lip, then the lower lip, and then other regions. Chronic eyelid swelling may occur.

Extrafacial swellings appear on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet and in the lumbar region. The pharynx and respiratory tract may be involved, with thickening of the mucous membrane. The relapsing condition produces an overgrowth of connective tissue, edema, and atrophy of the muscle fibers, with permanent deformities of the lips, cheeks, and tongue.

The cause of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is unknown. The association at times with megacolon, otosclerosis, and craniopharyngioma supports the theory of a neurotrophic origin. It may be familial. Histopathologic evaluation shows a tuberculoid type of granuloma with lymphedema and a banal perivascular infiltrate. Intralymphatic granulomas may account for the swelling.

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is frequently seen in an incomplete form, and other granulomatous diseases may present as swellings of the lips or orofacial tissues. It is worthwhile calling these, as a group, “orofacial granulomatosis” so that various underlying disease states or etiologic factors will not be missed when evaluating such patients. The differential diagnosis is the same as cheilitis granulomatosa (discussed earlier).

Intralesional injections of corticosteroids may be beneficial therapy. Again, combining this with oral antiinflammatory agents for long-term control, such as doxycycline, dapsone, colchicine, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, anti-TNF agents, or topical tacrolimus ointment, is an excellent strategy. Clofazimine and thalidomide are reported to be useful, but availability and side effects limit their use. Surgery alone may be used, or surgery combined with intralesional corticosteroid injections and oral medications may be more successful than any of the three alone. Compression therapy is another adjuvant intervention that may add improvement without side effects. Decompression of the facial nerve may be indicated in patients with recurrent attacks of facial palsy. Odontogenic infection has been reported to initiate this condition, and antibiotic therapy for this may lead to remission.

Al-Hamad A, et al: Orofacial granulomatosis. Dermatol Clin 2015; 33: 433.

Belliveau MJ, et al: Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome presenting with isolated bilateral eyelid swelling. Can J Ophthalmol 2011; 46: 286.

Bohra S, et al: Clinicopathological significance of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2015 Jul 31; 2015.

Feng S, et al: Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol 2014; 134: 977.

Li Z et al: Compression therapy. Eur J Dermatol 2011; 21: 1003.

Miest R, et al: Orofacial granulomatosis. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34: 505.

Fordyce Disease (Fordyce Spots)

Fordyce spots are ectopically located sebaceous glands, clinically characterized by minute, orange or yellowish, pinhead-sized macules or papules in the mucosa of the lips, cheeks, and less often the gums. Similar lesions may occur on the areolae, glans penis, and labia minora. Prominent lip involvement may result in a lipstick-like mark left on the rim of a glass mug after consuming a hot beverage (Meffert sign). Involvement of the labial mucosa with pseudoxanthoma elasticum may simulate Fordyce spots. Because the anomaly is asymptomatic and inconsequential, treatment should be undertaken only if there is a significant cosmetic problem. The carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) laser, electrodesiccation and curettage, bichloracetic acid, PDT, and isotretinoin are therapeutic options.

Chen PL, et al: Fordyce spots of the lip responding to electrodesiccation and curettage. Dermatol Surg 2008; 34: 960.

Errichetti E, et al: Areolar sebaceous hyperplasia associated with oral and genital Fordyce spots. J Dermatol 2013; 40: 670.

Stomatitis Nicotina

Also known as smoker’s keratosis and smoker’s patches, stomatitis nicotina is characterized by distinct, umbilicated papules on the palate. The ostia of the mucous ducts appear as red pinpoints surrounded by milky-white, slightly umbilicated, asymptomatic papules. The intervening mucosa becomes white and thick and tends to desquamate in places, leaving raw, beefy-red areas. Ulceration and the formation of aphthous ulcers may occur. Stomatitis nicotina is attributed to heavy smoking in middle-aged men, although it has also been reported in nonsmokers who habitually drink hot beverages. Heat may be the causative event. Indeed, the most severe cases are associated with the type of tobacco use that produces intense heat—pipe and reverse smoking. Treatment consists of abstaining from the use of tobacco or the ingestion of hot liquids.

Samatha Y, et al: Clinicopathologic evaluation of lesions associated with tobacco usage. J Contemp Dent Pract 2014; 15: 466.

Vellappally S, et al: Smoking related system and oral diseases. Acta Medica 2007; 50: 161.

Torus Palatinus

Torus palatinus is a bony protuberance in the midline of the hard palate, marking the point of junction of the two halves of the palate. It is asymptomatic. Exostoses also frequently occur in the floor of the mouth, involving the inner surface of the mandible.

Bennett WM: Torus palatinus. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1434.

Ladizinski B, Lee KC: A nodular protuberance on the hard palate. JAMA 2014; 311: 1558.

Fissured Tongue

Also known as furrowed tongue, scrotal tongue, or lingua plicata, fissured tongue is a congenital and sometimes familial condition in which the tongue is generally larger than normal, and plicate superficial or deep grooves are usually arranged so that there is a longitudinal furrow along the median raphe, reminiscent of scrotal rugae ( Fig. 34.7 ).

Fissured tongue is seen in Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and in many patients with Down syndrome. Individual case reports have been seen in association with pachyonychia congenita, pemphigus vegetans, and Cowden syndrome. Geographic tongue occurs together with fissured tongue in 50% of patients, and both are more often present in psoriasis patients than nonpsoriatic patients.

The condition gives rise to no difficulty, and treatment is not necessary, except that the deep furrows should be kept clean by use of mouthwashes. Herpetic geometric glossitis may mimic fissured tongue, but it is painful, affects predominantly immunocompromised individuals, and is centered on the back of the dorsal tongue.

Dafar A, et al: Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol Scand 2016; 74: 210.

Madani FM, et al: Normal variations of oral anatomy and common oral soft tissue lesions. Med Clin North Am 2014; 98: 1281.

Pedersen AML, et al: Oral mucosal lesions in older people. Oral Dis 2015: 21: 721.

Pereira CM, et al: Herpetic geometric glossitis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2010; 53: 133.

Picciani BL, et al: Geographic tongue and fissured tongue in 348 patients with psoriasis. ScientificWorldJournal 2015; 2015: 564326.

Geographic Tongue

Geographic tongue, also known as benign migratory glossitis, it is a manifestation of atopy, and in others, of psoriasis. It has been reported as being acquired in patients with AIDS or as a result of lithium therapy. In most, however, it is an isolated finding.

The dorsal surface of the tongue is the site usually affected. Geographic tongue begins with a small depression on the lateral border or the tip of the tongue, smoother and redder than the rest of the surface. This spreads peripherally, with the formation of sharply circumscribed, ringed or gyrate, red patches, each with a narrow, yellowish white border, making the tongue resemble a map. The appearance changes from day to day; patches may disappear in one place and manifest in another. The disease is characterized by periods of exacerbation and quiescence. The appearance may also remain unchanged in the same site for long periods. The condition is frequently unrecognized because it produces no symptoms except for the occasional complaint of glossodynia.

There are two clinical variants of geographic tongue. In one type, discrete, annular “bald” patches of glistening, erythematous mucosa with absent or atrophic filiform papillae are noted. Another type shows prominent circinate or annular, white raised lines that vary in width up to 2 mm. The clinical appearance and histopathologic findings of the tongue lesions in pustular psoriasis, reactive arthritis (Reiter syndrome), and geographic tongue are identical; when the tongue lesions occur with psoriasis or reactive arthritis, the name annulus migrans has been suggested for this entity ( Fig. 34.8 ).

Histologically, the main features are marked transepidermal neutrophil migration with the formation of spongiform pustules in the epidermis and an upper dermal mononuclear infiltrate. Although treatment is not usually necessary, a 0.1% solution of tretinoin applied topically has produced clearing within 4–6 days, and tacrolimus ointment may improve it.

Mangold AR, et al: Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34: 458.

Picciani BL, et al: Geographic tongue and psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol 2016; 91: 410.

Purani JM, Purani HJ: Treatment of geographic tongue with topical tacrolimus. BMJ Case Rep 2014 Aug 1; 2014.

Varoni E, Decani S: Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 670.

Black Hairy Tongue

Black or brown hairy tongue occurs on the dorsum of the tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae, where black, yellowish, or brown patches form, consisting of hairlike intertwining filaments several millimeters long ( Fig. 34.9 ). The “hairs” result from a benign hyperplasia of the filiform papillae of the anterior two thirds of the tongue, resulting in retention of long, conical filaments of orthokeratotic and parakeratotic cells. It occurs much more frequently in men than in women.

Black hairy tongue may be associated with several conditions that may be predisposing factors in its causation: smoking, use of oral antibiotics, interferon treatment, xerostomia, psychotropic drugs, and presence of Candida on the surface of the tongue.

This lesion may be differentiated both clinically and histologically from oral hairy leukoplakia, which is seen in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients. Hairy leukoplakia is usually seen on the lateral surface of the tongue, at first in corrugated patches, then with time, as solid white plaques that are adherent. Microscopic examination reveals acanthosis, parakeratosis, irregular projections of keratin, and vacuolated keratinocytes with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) present within them.

A toothbrush may be used to scrub off the projections, either alone, with 1%–2% hydrogen peroxide, or after application of tretinoin gel, 40% aqueous solution of urea, or papain (meat tenderizer). Such predisposing local factors as smoking, antibiotics, and oxidizing agents should be eliminated, if possible, and scrupulous oral hygiene maintained.

Arab JP, et al: Black hairy tongue during interferon therapy for hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol 2015; 14: 414.

Balaji G, et al: Linezolid induced black hairy tongue. Indian J Pharmacol 2014; 46: 653.

Gurvits GE, Tan A: Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 10845.

Thompson DF, et al: Drug-induced black hairy tongue. Pharmacotherapy 2010; 30: 585.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree