Dermatologic Bacteriology

John C. Hall MD

Bacteria exist on the skin as normal nonpathogenic resident flora or as pathogenic organisms. The pathogenic bacteria cause primary, secondary, and systemic infections. For clinical purposes it is justifiable to divide the problem of bacterial infection into three classifications (Table 21-1). Some of the diseases listed are of dubious bacterial etiology, but they appear bacterial, may have a bacterial component, can be treated with antibacterial agents, and are, therefore, included in this chapter.

With an alteration in immune capabilities in a person, bacteria and other infectious agents can have erratic behavior. Ordinary nonpathogens can act as pathogens, and pathogenic agents can act more aggressively.

Primary Bacterial Infections (Pyodermas)

The most common causative agents of the primary skin infections are the coagulase-positive micrococci (staphylococci) and the β-hemolytic streptococci. Superficial or deep bacterial lesions can be produced by these organisms. In managing the pyodermas, certain general principles of treatment must be initiated.

Improve bathing habits: More frequent bathing and the use of bactericidal soap, such as Dial, Cetaphil Antibacterial, or Lever 2000, are indicated. Any pustules or crusts should be removed during bathing to facilitate penetration of the local medications. In rare instances when these infections are recalcitrant to standard therapies, use half to one cup of bleach in a full tub of water to soak daily.

General isolation procedures: Clothing and bedding should be changed frequently and cleaned. The patient should have a separate towel and washcloth.

Systemic drugs: The patient should be questioned regarding ingestion of drugs that can cause lesions that mimic or cause pyodermas, such as iodides, bromides, testosterone, corticosteroids, progesterone, and lithium.

Diabetes: In chronic skin infections, particularly recurrent boils, diabetes should be ruled out by history and laboratory examination.

Immunosuppressed patients: A history of abnormal findings should alert the physician to the increasing number of patients now who are on chemotherapy for cancer, are posttransplant, or have the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

TABLE 21-1 ▪ Classification of Bacterial Infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Impetigo

Impetigo is a common superficial bacterial infection seen most often in children. It is the “infantigo” every parent respects.

Primary Lesions

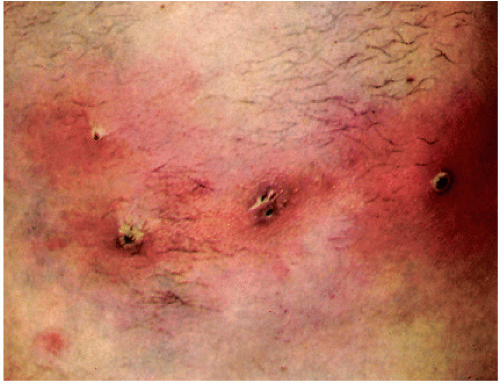

The lesions vary from small vesicles to large bullae that rapidly rupture and discharge a honey-colored serous liquid (Fig. 21-1). New lesions can develop in a matter of hours. The blisters are evanescent and often are not present but leave their oval or scalloped edges.

Secondary Lesions

Crusts form from the discharge and appear to be lightly stuck on the skin surface. When removed, a superficial erosion remains, which may be the only evidence of the disease. In debilitated infants, the bullae may coalesce to form an exfoliative type of infection called Ritter’s disease or pemphigus neonatorum.

Distribution

The lesions occur most commonly on the face but may be anywhere.

Contagiousness

It is not unusual to see brothers or sisters of the patient and, rarely, the parents similarly infected.

Differential Diagnosis

Contact dermatitis due to poison ivy or oak: Linear blisters and itches severely (see Chapter 8).

Tinea of smooth skin: Fewer lesions; spreads slowly; central clearing; small vesicles in an annular configuration and elevated edge; fungi found on scraping; culture is positive (see Chapter 25).

Toxic epidermal necrolysis: In infants and rarely in adults, massive bullae can develop rapidly, particularly with staphylococcal infection. The severe form of this infection is known as the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which is a type of toxic epidermal necrolysis (see Chapter 18).

SAUER’S NOTES

Body piercing has frequently been associated with localized staphylococcal infection and pseudomonas infection and rarely bacteremia and endocarditis. Tuberculosis, hepatitis C and B, and even HIV can be transmitted in this way. Noninfectious complications include keloids and allergic dermatitis. This fad should not be recommended, especially in the tongue, lips, navels, nipples, nose, or genitalia.

Treatment

1. Outline the general principles of treatment. Emphasize the removal of the crusts once or twice a day during bathing with an antibacterial soap such as Lever 2000 or chlorhexidine (Hibiclens) skin cleanser.

2. Mupirocin (Bactroban) or gentamicin (Garamycin) ointment or Polysporin ointment q.s. 15.0 Sig: Apply t.i.d. locally for 10 days. Treat all affected family members or other affected contacts.

3. Oral antibiotics such as a 10-day course of erythromycin, cephalexin, or clindamycin may be necessary.

4. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the community-acquired form (CA-MRSA) now occurs in epidemic proportions. Fortunately it often is sensitive to sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim (Septra or Bactrim), clindamycin, or tetracycline derivatives. Abscesses are common and when present must be treated aggressively by incision and drainage.

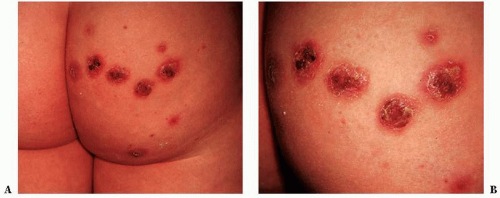

Ecthyma

Ecthyma is another superficial bacterial infection, but it is seen less commonly and is deeper than impetigo. It is usually caused by β-hemolytic streptococci and occurs on the buttocks and the thighs of children (Fig. 21-2).

Primary Lesion

A vesicle or vesiculopustule appears and rapidly changes into the secondary lesion.

FIGURE 21-2 ▪ (A) Ecthyma on the buttocks of 13-year-old boy. (B) Closeup of lesions. (Courtesy of Burroughs Wellcome Co.) |

SAUER’S NOTES

1. I sometimes add sulfur 5% and hydrocortisone 1% to 2% to the antibiotic cream or ointment for treatment of impetigo and other superficial pyodermas. Many patients with impetigo whom I see have been using a plain antibiotic salve with an oral antibiotic, and the impetigo persists. With this compound salve the impetigo heals.

2. Advise the patient that the local treatment should be continued for 5 days after the lesions apparently have disappeared to prevent recurrences “therapy plus.”

3. Systemic antibiotic therapy: Some physicians believe that every patient with impetigo should be treated with systemic antibiotic therapy to heal these lesions and also to prevent chronic glomerulonephritis. Erythromycin in appropriate dosages for 10 days would be effective in most cases. Resistance to erythromycin can occur, and then dicloxacillin or cephalexin are effective. Erythromycin-inducible clindamycin resistance is becoming more common. Bacterial sensitivity testing helps to guide appropriate antibiotic therapy. There is a dramatic increase in the United States in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) and I am using sulfamethoxaxole/trimethoprim as an initial option more often.

Secondary Lesion

This is a piled-up crust, 1 to 3 cm in diameter, overlying a superficial erosion or ulcer. In neglected cases, scarring can occur as a result of extension of the infection into the dermis.

Distribution

Age Group

Children are the most common age group affected.

Contagiousness

Ecthyma is rarely found in other members of the family.

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis: Less common in children; whitish, firmly attached scaly lesion, also on the scalp, knees, and/or elbows (see Chapter 14).

Impetigo: Much smaller crusted lesions, not as deep (see preceding section).

Treatment

1. The general principles of treatment are listed earlier in the chapter. The crusts must be removed daily. Response to therapy is slower than with impetigo, but the treatment is the same for both conditions.

2. Systemic antibiotics: If there is a low-grade fever and evidence of bacterial infection in other organs due to sepsis, one of the antibiotic syrups or tablets can be given orally for 10 days. This is commonly seen in children with extensive ecthyma. It is rarely seen with impetigo.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis is a common pyogenic infection of the hair follicles, usually caused by coagulase-positive staphylococci (Fig. 21-3). Seldom does a patient consult the physician for a single outbreak of folliculitis. The physician is consulted because of recurrent and chronic pustular lesions. The patient realizes that the present acute episode clears with the help of nature, but seeks medicine and advice to prevent recurrences. For this reason, the general principles of treatment are listed. The physician must pay particular attention to the drug history and the diabetes investigation. Some physicians believe that a focus of infection in the teeth, tonsils, gallbladder, or genitourinary tract should be ruled out when folliculitis is recurrent.

FIGURE 21-3 ▪ (A) Folliculitis of the scalp. (B) Folliculitis of the beard area (Courtesy of Burroughs Wellcome Co.). |

The folliculitis may invade only the superficial part of the hair follicle, or it may extend down to the hair bulb. Many variously named clinical entities based on the location and the chronicity of the lesions have been carried down through the years. A few of these entities bear presentation here, but most are defined in the Dictionary-Index.

Superficial Folliculitis

The physician is rarely consulted for this minor problem, which is most commonly seen on the arms, scalp, face, and buttocks of children and adults with the acne-seborrhea complex. A history of excessive use of hair oils, bath oils, moisturizers, or suntan oils can often be obtained. The use of these oily agents should be avoided. Culture for Staphylococcus or Streptococcus may be negative and in these cases, the same therapeutic regiments that are usually used for acne should be used. Chronic noninfectious folliculitis is the term I use for this clinical picture.

Folliculitis of the Scalp (Superficial Form)

A superficial form has the appellation acne necrotica miliaris. This is an annoying, pruritic, chronic, recurrent folliculitis of the scalp in adults. The scratching of the crusted lesions occupies the patient’s evening hours.

Treatment.

1. Follow the general principles of treatment.

2. Selenium sulfide (Selsun, Head & Shoulders Intensive Treatment) suspension shampoo 120.0

Sig: Shampoo twice a week as directed on the label.

3. Other shampoos such as T-Sal and sulfur washes, such as Ovace, Plexion, or a generic form of these used as a shampoo, can be tried.

SAUER’S NOTES

My routine for chronic folliculitis cases includes the following:

1. Sulfur ppt. 5% Hydrocortisone 1% Bactroban cream q.s. 15.0

Sig: Apply b.i.d. locally.

2. Long-term low-dose antibiotic therapy can be used, such as erythromycin, 250 mg, q.i.d. for 3 days then two or three times a day for months.

3. Lichenified papules of excoriated folliculitis respond to superficial liquid nitrogen applications or intralesional corticosteroid injections.

4. Antibiotic and corticosteroid cream mixture q.s. 15.0

Sig: Apply to scalp h.s.

Folliculitis of the Scalp (Deep Form)

The deep form of scalp folliculitis is called folliculitis decalvans. This is a chronic, slowly progressive folliculitis with an active border and scarred atrophic center. The end result, after years of progression, is patchy, scarred areas of alopecia, with eventual burning out of the inflammation. It is not a true infection and bacterial cultures are negative. Long-term tetracycline derivatives may be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis.

Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus: Redness, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation; enlarged hair follicles with follicular plugs (see Chapter 37).

Alopecia cicatrisata (pseudopelade of Brocq): Rare; no evidence of inflammation. Some authors think this is burnt out lichen planus of the scalp (see Chapter 32).

Tinea of the scalp: It is important to culture the hair for fungi in any chronic infection of the scalp; Trichophyton tonsurans group can cause a subtle noninflammatory clinical picture (black dot tinea in children, which is endemic in large urban areas in African-American children who braid their hair) (see Chapter 25).

Excoriated folliculitis: Chronic thickened excoriated papules or nodules (can be called prurigo nodularis), usually seen on the posterior scalp, posterior neck, anus, and legs. When allowed to heal, whitish scars remain. The inflammation can last for years. Liquid nitrogen applied to the papules is effective, as are intralesional corticosteroids. Occasionally, these patients can be treated with a drug to decrease obsessive-compulsive behavior, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Common in dialysis patients and can be seen in hepatitis C and AIDS.

Lichen planopilaris: Scarring lichen planus in the scalp, which is usually characteristic on biopsy. It may have follicular plugging and is characterized by perifollicular cuffing of fine adheren scale and a purplish pink color. Topical or intralesional corticosteriods and antimalarials are often used with success.

Treatment. Results of treatment may be disappointing. Long-term antibiotics, especially tetracycline derivatives, may be helpful. Occasionally intralesional corticosteroids may be palliative.

Folliculitis of the Beard

This is the familiar “barber’s itch,” which in the days before antibiotics was resistant to therapy. This bacterial infection of the hair follicles is spread rather rapidly by shaving.

Differential Diagnosis.

Contact dermatitis caused by shaving lotions: History of new lotion applied; general redness of the area with some vesicles (see Chapter 8).

Tinea of the beard: Very slowly spreading infection; hairs broken off; usually a deeper, nodular type of inflammation (Majocchi’s granuloma); culture of hair produces fungi (see Chapter 25).

Ingrown beard hairs (pseudofolliculitis barbae): Hair circling back into the skin with resultant chronic inflammation; a hereditary trait, especially in African-Americans. Close shaving aggravates the condition. Local antibiotics rarely help, but locally applied depilatories may help. Other local therapy to consider is Retin-A gel and Benzashave (shaving cream with benzoyl peroxide). Permanent hair removal by electrolysis or laser can be helpful. Vaniqa applied twice a day after hair removal can be used to reduce the rate of regrowth of hair. Growing a beard or mustache eliminates the problem. Hairs may also become ingrown in axillae, pubic area, or legs, especially when closely shaved in places with curly hair.

Treatment.

1. Follow the general principles of treatment, stressing the use of Dial or other antibacterial soap for washing of the face.

2. Shaving instructions:

Change the razor blade daily or sterilize the head of the electric razor by placing it in 70% alcohol for 1 hour.

Apply the following salve very lightly to the face before shaving and again after shaving. Do not shave closely.

3. Antibiotic and hydrocortisone cream mixture q.s. 15.0

Sig: Apply to the face before shaving, after shaving, and at bedtime.

Comment: For stubborn cases, add sulfur 5% to the cream.

4. Oral therapy with erythromycin, 250 mg (can also use cephalexin on clindamycin)

Sig: one capsule q.i.d. for 7 days, then one capsule b.i.d. for 7 days.

Sty (Hordeolum)

A sty is a deep folliculitis of the stiff eyelid hairs. A single lesion is treated with hot packs of 1% boric acid solution and an ophthalmic antibiotic ointment. Recurrent lesions may be linked with the blepharitis of seborrheic dermatitis (dandruff) or rosacea. For this type, vytone or cleansing the eyelashes with Johnson’s baby shampoo is indicated. If it is a chronic problem then tetracycline antibiotics short term or long term can be used.

Furuncle

A furuncle, or boil (Fig. 21-4), is a more extensive infection of the hair follicle, usually due to Staphylococcus. A boil can occur in any person at any age, but certain predisposing factors account for most outbreaks. An important factor is the acne-seborrhea complex (oily skin and a history of acne and dandruff). Other factors include poor hygiene, diabetes, local skin trauma from friction of clothing, and maceration in obese persons. One boil usually does not bring the patient to the physician, but recurrent boils do.

Differential Diagnosis.

Single Lesion

Primary chancre-type diseases: See list in Dictionary-Index.

Multiple Lesions

Drug eruption from iodides or bromides: See Chapter 8.

Hidradenitis suppurativa: See later in this chapter.

Treatment

Case Example: A young man has had recurrent boils for 6 months. He does not have diabetes, is not obese, is taking no drugs, and bathes daily. He now has a large boil on his buttocks.

1. Burow’s solution hot packs.

Sig: 1 packet of Domeboro powder to 1 quart of hot water. Apply hot wet packs for 30 minutes twice a day.

2. Incision and drainage: This should be done only on “ripe” lesions where a necrotic white area appears at the top of the nodule. Drains are not necessary unless the lesion has extended deep enough to form a fluctuant abscess. If near the rectum, consider a perirectal abscess as the diagnosis. This has a communicating tract with the rectum, which must be treated surgically. Referral to a general surgeon or proctologist is indicated.

3. Oral antistaphylococcal penicillin, such as dicloxacillin or cephalexin, should be prescribed for 5 to 10 days. (Bacteriologic culture and sensitivity studies are helpful in determining which antibiotic to use.) I often now use sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim empirically to cover MRSA before culture results are known.

4. For recurrent form:

Follow general principles of treatment by use of an antibacterial soap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree