Dermatologic Allergy

John C. Hall MD

This chapter will discuss contact dermatitis, industrial dermatoses, atopic eczema, and drug eruptions because of their obvious allergenic factors. However, it is important to keep in mind that some cases of contact dermatitis and industrial dermatitis are caused by irritants. Nummular eczema will also be discussed in this chapter because it resembles some forms of atopic eczema and may even be a variant of atopic eczema.

Contact Dermatitis

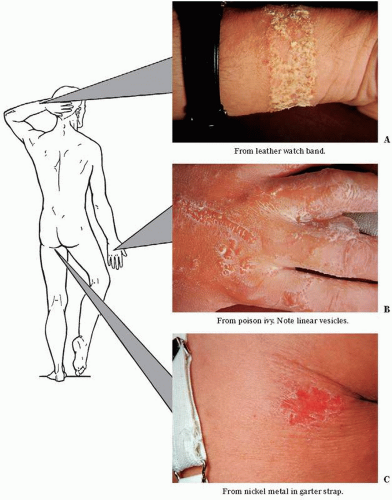

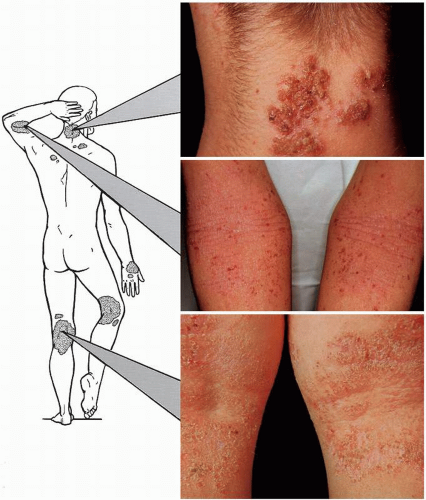

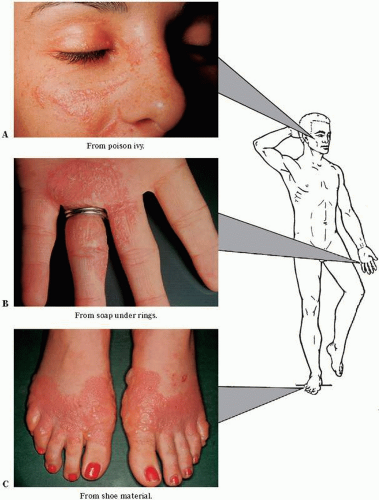

Contact dermatitis (Figs. 8-1,8-2,8-3,8-4), or dermatitis venenata, is a very common inflammation of the skin caused by the exposure of skin to either primary irritant substances, such as soaps, or allergenic substances, such as poison ivy resin. Industrial dermatoses are also included at the end of this section.

Presentation

Primary Lesions

Any of the stages, from mild redness, edema, or vesicles to large bullae with a marked amount of oozing, can be seen in primary lesions. This is usually limited to sites where the contactant touches the skin. However, when the reaction is severe, it can flare beyond these sites of contact. With poison ivy, oak, and sumac, a black stain on skin or clothing can sometimes be seen.

Secondary Lesions

Crusting from a secondary bacterial infection, excoriation, or lichenification occurs in secondary lesions. When the local site is severely affected, a generalized eruption can occur in a symmetrical and widespread distribution. This is called an id or autoeczematous eruption. It commonly causes vesicles on the palms, soles, and sides of the fingers and toes. It can be generalized and is symmetric. It is also very pruritic.

Distribution and Causes

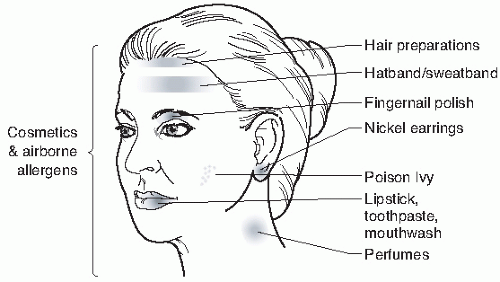

Any agent can affect any area of the body. However, certain agents commonly affect certain skin areas.

Face and neck (Fig. 8-5): cosmetics, soaps, insect sprays, ragweed, perfumes or hair sprays (sides of neck), fingernail polish (eyelids), hat bands (forehead), mouthwashes, toothpaste, lipstick (perioral), nickel metal (under earrings), necklaces and collars (neck), industrial oil (facial chloracne).

Hands and forearms: soaps, hand lotions, wristbands, industrial chemicals, poison ivy, and a multitude of other agents. Irritation from soap often begins under rings as do allergic reactions from nickel (common) (dimethylglyoxime testing can be used to see if nickel is present in a metal object such as jewelry) or gold (rare). Latex from gloves can cause a contact dermatitis and contact urticaria. It can be associated with life-threatening anaphylaxis and is becoming an increasing danger because of the increased use of latex gloves and latex contraceptives.

Axillae: deodorants, dress shields, detergents, bleaching agents, fabric softeners, antistatic agents, and dry cleaning solutions.

Trunk: clothing that is new and not previously cleaned (because it contains a formaldehyde resin), clothing with rubber or metal attached to it (commonly seen on the central abdomen from the metal clasp found in jeans), and transdermal drug patches from the adhesive or the drug.

Anogenital region: douches, dusting powder, diapers in infants or adults, contraceptives, colored toilet paper, topical hemorrhoid preparations, poison ivy, or topicals for treatment of pruritus ani, candida, and fungal infections.

Feet: shoes, foot powders, topical agents for athlete’s foot infections.

Generalized eruption: volatile airborne chemicals (paint, spray, ragweed), medicaments locally applied to large areas, bath powders, or clothing (especially if not previously washed).

Course

Duration can be very short (sometimes only days) or quite long (weeks, months, or even years). As a general rule, successive recurrences become more chronic and more severe (e.g., seasonal ragweed dermatitis can evolve into a year-round dermatitis). Once established in patients, hypersensitivity reactions are seldom lost. However, years of exposure without a reaction may occur before sensitization takes

place. Also, certain people are more susceptible to allergic and irritant contact dermatoses than others. This is particularly true in patients who already have inflamed skin. An example of this is how irritants commonly cause contact dermatitis in patients with eczema. A very careful seasonal history regarding the onset, especially in chronic cases, may lead to the discovery of an unsuspected causative agent such as ragweed.

place. Also, certain people are more susceptible to allergic and irritant contact dermatoses than others. This is particularly true in patients who already have inflamed skin. An example of this is how irritants commonly cause contact dermatitis in patients with eczema. A very careful seasonal history regarding the onset, especially in chronic cases, may lead to the discovery of an unsuspected causative agent such as ragweed.

FIGURE 8-1 ▪ Contact dermatitis. (A) From poison ivy. (B) From soap under rings. (C) From shoe material. (Courtesy of Burroughs Wellcome Co.) |

An eczematous reaction (e.g., the blister fluid of poison ivy) contains no allergen that can cause the dermatitis in another person or in other areas on the same person. However, if the poison ivy oil or other allergen remains on the clothes of the affected person, contact with those clothes of a susceptible person could cause a contact dermatitis. Smaller amounts of oil can cause a dermatitis even weeks after exposure and may make the patient think the allergen is systemic

or bloodborne. The hair or fur of animals, as well as utensils used in hunting or gardening, can also transfer the allergenic oleoresin of poison ivy.

or bloodborne. The hair or fur of animals, as well as utensils used in hunting or gardening, can also transfer the allergenic oleoresin of poison ivy.

Laboratory Findings

Patch tests (see Chapter 2) are valuable in eliciting the cause of a contact dermatitis. However, careful interpretation is required by the clinician.

Differential Diagnosis

A contact reaction must be considered and ruled in or out in any case of eczematous or oozing dermatitis on any body area.

Treatment

Two of the most common contact dermatoses seen in the physician’s office are poison ivy (or poison oak or sumac)

and hand dermatitis. The treatments for these two conditions will be discussed separately.

and hand dermatitis. The treatments for these two conditions will be discussed separately.

Treatment of Contact Dermatitis Owing to Poison Ivy

Case Example: A patient comes to the office with a linear, vesicular dermatitis of the feet, hands, and face. He states that he spent the weekend fishing and that the rash broke out the following day. The itching is rather severe but not enough to keep him awake at night. He had “poison ivy” 5 years ago.

First Visit.

1. There are several mistaken notions about poison ivy dermatitis. Assure the patient that he cannot pass on the

dermatitis to his family or spread it on himself from the blister fluid. The flexor fingers or palms have a very thick keratin layer that the allergen cannot penetrate. However, the allergen can be spread over the rest of the body, from the fingers to other areas of the body.

dermatitis to his family or spread it on himself from the blister fluid. The flexor fingers or palms have a very thick keratin layer that the allergen cannot penetrate. However, the allergen can be spread over the rest of the body, from the fingers to other areas of the body.

FIGURE 8-4 ▪ Contact dermatitis of the hand. This common dermatitis is usually due to continued exposure to soap and water. (Courtesy of K.U.M.C.; Burroughs Wellcome Co.) |

2. Suggest that the clothes worn while fishing need to be washed in warm soapy water to remove the allergenic resin.

3. Prescribe Burow’s solution wet packs.

Sig: Add one packet of powder (Domeboro) to 1 quart of cool water. Apply sheeting or toweling, wet with the solution, and apply to the blistered areas for 20 minutes twice a day. The wet packs need not be removed during the 20-minute period. (For a more widespread case of poison ivy dermatitis, take cool baths with a half box of Aveeno [colloidal oatmeal] or soluble starch in a tub. This will give considerable relief from the itching.)

4. 1% Hydrocortisone lotion q.s. 60.0 (1% Hytone [available OTC] lotion, 1% hydrocortisone (HC) Pramosone lotion (contains the antipruritic antihistamine pramoxine) among others. Cheaper OTC pramoxine-containing topicals can also be used.

SAUER’S NOTES

1. In obtaining a history, question the patient carefully about home, over-the-counter (OTC), other physicians’, or well-meaning friends’ remedies. Contact dermatitis on top of another contact dermatitis is quite common.

2. When you are unable to find the cause of a generalized contact dermatitis, determine the site of the initial eruption and think of the agents that touched that area.

3. When prescribing topical therapy emphasize that all other topical medications should be stopped.

Sig: Apply t.i.d. and PRN for itching on affected areas.

5. Chlorpheniramine maleate tablets, 4 mg 60 (many other antihistamines are available as sedating or nonsedating [probably not as effective] varieties; some are OTC).

Sig: Take 1 tablet t.i.d. (for relief of itching). Comment: Warn patient about the side effect of drowsiness. This drug is available OTC and is less expensive than if written as a prescription.

6. Use cortisone-type injection IM. Short but rapid-acting corticosteroids are moderately beneficial, such as betamethasone (Celestone Soluspan) (8 mg/mL in a dose of 1 to 2 mL subcutaneously), or dexamethasone (Decadron-LA) (8 mg/mL in a dose of 1 to 1.5 mL IM). Triamcinolone (Kenalog) 20 to 40 mg IM can also be given. Caution the patient about a possible change in insulin requirements in diabetics as well as possible mood alterations with insomnia and jitteriness.

Subsequent Visits.

1. Continue the wet packs only as long as there are blisters and oozing. Extended use is too drying for the skin.

2. After 3 or 4 days of use, the lotion may be too drying. Substitute fluorinated corticosteroid emollient cream q.s. 60.0.

Sig: Apply a small amount locally t.i.d., or more often if itching is present.

SAUER’S NOTES

1. Most failures in the therapy for severe poison ivy or oak dermatitis result from the failure to continue the oral corticosteroid for 10 to 14 days or longer.

2. Medrol Dosepak therapy may not provide enough days of treatment at a high enough dose for some cases of poison ivy dermatitis.

3. Explain to the patient that it is common for new lesions, even blisters, to continue to pop out during the entire duration of the eruption.

Severe Cases of Poison Ivy Dermatitis.

An oral corticosteroid is indicated in severe cases of poison ivy dermatitis: prednisone, 10 mg #30.

Sig: Take 5 tablets each morning for 2 days, 4 tablets each morning for 2 days, 3 tablets each morning for 2 days, 2 tablets each morning for 2 days, and 1 tablet each morning for 2 days. Take with food in the morning. Repeat if not improving sufficiently.

The use of a poison ivy vaccine orally or IM is contraindicated during an acute episode. Desensitization may occur after a long course of oral ingestion of graduated doses of the allergen, but pruritus ani, generalized pruritus, and urticaria probably make the treatment worse than the disease. Desensitization does not occur after a short course of IM injections of the vaccine, and this form of prophylactic therapy is worthless. Barrier creams may decrease dermatitis if applied before exposure; examples include Hydropel and Ivy Block.

A window of up to 2 hours may exist where washing the skin with a surfactant (e.g., Dial soap) and oil-removing compound (e.g., soap or Goop) or a chemical inactivator (e.g., Tecnu) may ameliorate or prevent the contact dermatitis.

Treatment of Contact Dermatitis of the Hand Owing to Soap

Case Example: A young housewife states that she has had a breakout on her hands for 5 weeks. The dermatitis developed about 4 weeks after the birth of her last child. She states that she had a similar eruption after her previous two pregnancies. She has used a lot of local medication of her own, and the rash is getting worse instead of better. The patient and her immediate family never had any asthma, hay fever, or eczema.

Examination of the patient’s hands reveals small vesicles on the sides of all of her fingers, with a 5-cm area of oozing and crusting around her left ring finger.

First Visit.

1. Assure the patient that the hand eczema is not contagious to her family.

2. Inform the patient that soap irritates the dermatitis and that it must be avoided as much as possible. A homemaker will find this avoidance very difficult. One of the best remedies is to wear protective gloves when extended soap-and-water contact is unavoidable. Rubber gloves alone produce a considerable amount of irritating perspiration, but this is absorbed when thin white cotton gloves are worn under the rubber gloves. Lined rubber gloves are not as satisfactory because the lining eventually becomes dirty and soggy and cannot be cleaned easily. Bluettes is an excellent protective glove with a cotton lining.

SAUER’S NOTES

1. “Housewives’ eczema” cannot usually be treated successfully with a corticosteroid salve alone without observing the other protective measures.

2. After the dermatitis is clear, it is very important to advise the patient to treat the area for at least 1 more week to prevent a recurrence. I call this “therapy plus.”

3. For body and hand cleanliness, a mild soap, such as Dove, can be used, or any of the following: Cetaphil soapless cleanser, Basis soap, and Neutrogena soaps.

4. Tell the patient that these prophylactic measures must be adhered to for several weeks after the eruption has apparently cleared, or there will be a recurrence. Injured skin is sensitive and needs to be pampered for an extended time.

5. Burow’s solution soaks.

Sig: Add 1 packet of powder (Domeboro) to 1 quart of cool water. Soak hands for 15 minutes twice a day.

6. Fluorinated corticosteroid ointment (see Formulary in Chapter 4) 15.0 gms

Sig: Apply sparingly, locally, q.i.d. especially after shower and hand washing

Resistant, Chronic Cases.

1. To the corticosteroid ointment add, as indicated, sulfur (3% to 5%), coal tar solution (3% to 10%), or an antipruritic agent such as menthol (0.25%) or camphor (2%).

2. Oral corticosteroid therapy. A short course of such therapy rapidly improves or cures a chronic dermatitis. Attempt to avoid repeating more than is absolutely necessary.

3. Prevention of flares of contact dermatitis can be accomplished by frequent use of emollient preparations. Curel, Cetaphil hand cream, Eucerin Plus lotion, CeraVe, and Neutrogena Norwegian hand cream are examples. Bag Balm or Udder Cream are odiferous and less cosmetically acceptable choices.

Occupational Dermatoses

Sixty-five percent of all the industrial diseases are dermatoses. The most common cause of these skin problems is contact irritants, of which cutting oils are the worst offenders. Lack of adequate cleansing is a big contributing factor to cutting oil dermatitis. On the other hand, harsh or abrasive cleansers can aggravate the dermatitis.

It is not possible to list the thousands of different chemicals used in the hundreds of varied industrial operations that have the potential of causing a primary irritant reaction or an allergic reaction on the skin surface. Excellent books on the subject of occupational dermatitis are listed in the bibliography section at the end of this chapter.

Management of Industrial Dermatitis

Case Example: A cutting-tool laborer presents with a pruritic, red, vesicular dermatitis of 2 months’ duration on his hands, forearms, and face.

1. Obtain a careful, detailed history of his type of work and any recent change, such as use of new chemicals or new cleansing agents or exposure at home with hobbies, painting, and so on. Question him concerning remission of the dermatitis on weekends or while on vacation.

2. Question the patient concerning the first aid care given at the plant. Too often, this care aggravates the dermatitis. Bland protective remedies should be substituted for potential sensitizers such as sulfonamide and neomycin salves, antihistamine creams, benzocaine ointments, nitrofuran preparations, and strong or sensitizing antipruritic lotions and salves.

3. Treatment of the dermatitis with wet compresses, bland lotions, or salves is the same as for any contact dermatitis (see previous discussion). Unfortunately, many of the occupational dermatoses respond slowly to therapy. This is due in part to the fact that most patients continue to work and are exposed, repeatedly, to small amounts of the irritating chemicals, even though precautions are taken. Also, certain industrial chemicals, such as chromates, beryllium salts, and cutting oils, injure the skin in such a way as to prevent healing for months and years and result in a chronic eczema or chronic psoriasis (Koebner phenomena) in prone individuals.

4. Transferring a patient to a new job in the same work setting where exposure is less intensive may be helpful. Protective clothing such as gloves (being sure not to make the patient too awkward around dangerous machines) or protective creams (Tetrix, EpiCeram skin barrier emulsion) or sprays (Pro Q topical, OTC aerosol foam) can be beneficial. Barrier creams include Hollister Moisture Barrier, Mentor Shield Skin, Hydrogel, Uniderm, and Dermofilm.

5. The legal complications with compensation boards, insurance companies, the industry, and the injured patient can be discouraging, frustrating, and time consuming. However, most patients are not malingerers, and they do expect and deserve proper care and compensation for their injuries.

A comprehensive paper by Gordon C. Sauer on the percentages of skin impairment is entitled “A Guide to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment of the Skin” (Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:566). A similar guide published by the American Medical Association in 1990 is listed in the bibliography section at the conclusion of this chapter.

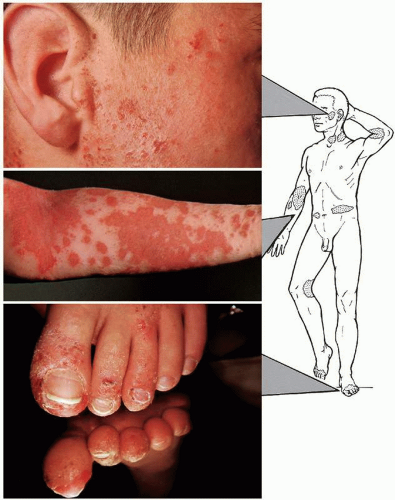

Atopic Eczema

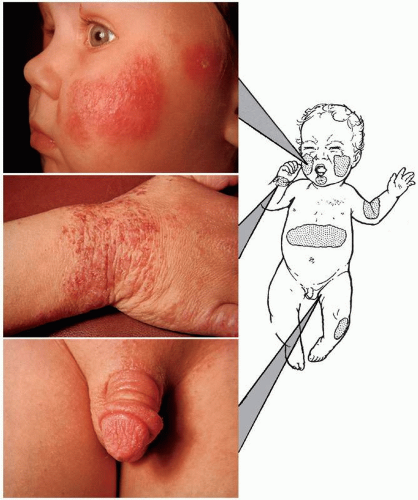

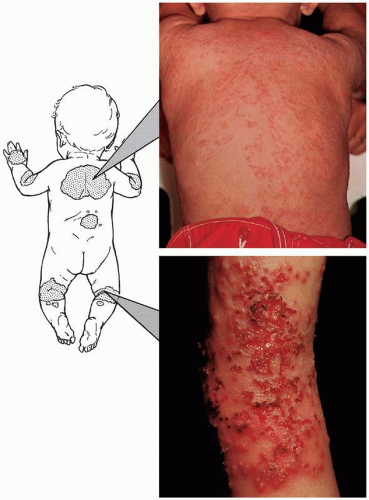

Atopic eczema (Figs. 8-6,8-7,8-8,8-9,8-10; Table 8-1), or atopic dermatitis, is a rather common, markedly pruritic, chronic skin condition that occurs in two clinical forms: infantile and adult.

Clinical Lesions

Infantile form: blisters, oozing, and crusting, with excoriation.

Adolescent and adult forms: marked dryness, thickening (lichenification), excoriation, and even scarring.

Distribution

Infantile form: on the face, scalp, arms, legs, or generalized. The diaper area is usually clear, probably because of occlusion of the area and urea exposure from urine.

Adolescent and adult forms: on the cubital and popliteal fossae and, less commonly, on the dorsa of the hands and feet, ears, or generalized. Atopic eczema of the soles of the feet is quite common in adolescents. In adults, there is a more chronic, localized disease, especially involving the genitalia, posterior scalp, and ankles (often referred to as lichen simplex chronicus [LSC]). Pruritus is severe and paroxysmal.

Course

The course varies from a mild single episode to severe chronic, recurrent episodes resulting in the “psychoitchical” person. Eczema is referred to as “the itch that rashes.” The infantile form usually becomes milder or even disappears after the age of 3 or 4 years, and approximately 70% of cases clear by puberty. During puberty and the late teenage years, flare-ups or new outbreaks can occur. Adult-onset eczema, once thought to be rare, is actually quite common. Young housewives or househusbands may have their first recurrence of atopic eczema since childhood because of their new jobs of

dishwashing and child care. Thirty percent of patients with atopic dermatitis eventually develop allergic asthma or hay fever, penicillin allergy, hives, or marked reaction to insect bites.

dishwashing and child care. Thirty percent of patients with atopic dermatitis eventually develop allergic asthma or hay fever, penicillin allergy, hives, or marked reaction to insect bites.

Causes

The following factors are important:

Heredity is the most important single factor. The family history is usually positive for one or more of the triad of allergic diseases: asthma, hay fever, or atopic eczema. Penicillin allergy, hives, and a marked reaction to insect bites are also a part of the atopic diathesis, which is called type 1 or anaphylactoid immunity. Determination of this history in cases of hand dermatitis is important because it often enables the physician, on the patient’s first visit, to prognosticate a more drawnout recovery than if the patient had a simple contact dermatitis.

FIGURE 8-8 ▪ Atopic eczema. The bottom photograph, by the use of a mirror, demonstrates the undersurface of the toes. (Courtesy of Sandoz Pharmaceuticals.) |

Dryness of the skin is important. Most often, atopic eczema is worse in the winter owing to the decrease in home or office and outdoor humidity. For this reason, the use of soap and water should be reduced and hot water avoided. Emollients (lanolin free) can be applied after bathing.

Wool and lanolin (wool fat) commonly irritate the skin of these patients. Wearing wool or silk clothes may be another reason for an increased incidence of atopic eczema in the winter. Cotton clothes and bed clothing are preferred.

Allergy to foods is a factor that is often overstressed, particularly with the infantile form. The mother’s history of certain foods causing trouble should be a guide for eliminating foods. This can be tested by adding the incriminated foods to the diet, one new

food every 48 hours, when the dermatitis is stable. Scratch tests and intracutaneous tests uncover very few dermatologic allergens.

Emotional stress and nervousness aggravate any existing conditions such as itching, duodenal ulcers, or migraine headaches. Therefore, this “nervous” factor is important but not causative enough to label this disease disseminated neurodermatitis.

Concomitant bacterial infection of the skin, particularly with Staphylococcus aureus, is common. Cultures may be helpful to guide antibiotic choices. Community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has become ubiquitous.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree