Abstract

Cutaneous drug reactions account for a large proportion of adverse drug reactions, can be very challenging to diagnose, and can mimic many other skin diseases. This chapter includes a review of general principles, mechanisms, and clinical manifestations of cutaneous drug eruptions. We have classified drug eruptions by morphology; exanthematous, urticarial, pustular, and bullous. Within each of these groups we have divided them into simple, benign or nonfebrile, and complex or febrile reactions. We also include a miscellaneous group to ensure a methodical review. Diagnostic maneuvers are discussed, and an algorithm is presented to enable the clinician to attain a reasonable level of diagnostic certainty about the responsible drug. Cutaneous drug eruptions can be important dermatologic signs of systemic disease.

Keywords

Bullous, Complex, Drug eruptions, Exanthematous, Pustular, Urticarial

- •

Prevent harm: Be aware of high-risk drugs and always consider a drug reaction as part of a differential diagnosis.

- •

Monitoring: Monitor for systemic involvement.

- •

Diagnosis: Determine the morphology of the eruption and decide if it is simple or complex.

- •

Management and treatment: After a causality assessment, stop most likely potential drugs when clinically appropriate.

Introduction

Cutaneous drug reactions account for a large proportion of adverse drug reactions. Cutaneous drug reactions can be very challenging to diagnose. They can mimic many other skin diseases; this is especially evident during childhood when viral exanthems are commonplace. If a patient is taking numerous medications, establishing causality to a specific drug can be difficult.

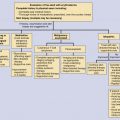

This chapter includes a review of general principles, mechanisms, and clinical manifestations of cutaneous drug eruptions. We have classified different types of drug eruptions by morphology: exanthematous, urticarial, pustular, and bullous. Within each of these groups we have divided them into simple, benign, or nonfebrile and complex or febrile reactions. We also include a miscellaneous group to ensure a methodical review. Diagnostic maneuvers are discussed, and an algorithm is presented to enable the clinician to attain an idea about the possible responsible drug.

There are a number of ways to classify drug reactions. Our classification is a widely accepted and simplified approach based on morphology and subdivided into simple and complex to take into account systemic features. Alternative common methods of classification are either to divide reactions into Type A (predictable, acute, related to mechanism of action) or Type B (idiosyncratic, unpredictable, and not related to mechanism of action), versus classifying reactions based on the type of immunologic response (immediate IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, cytotoxic reactions, immune-complex-mediated reactions, and T-cell-mediated/delayed type reactions).

Epidemiology of Cutaneous Drug Reactions

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs) are a commonly reported type of adverse drug reaction (ADR) and can lead to frequent clinical visits and discontinuation of therapy. Dermatologic reactions are the most common manifestation of systemic drug hypersensitivity. Up to 2% to 3% of all hospitalized patients experience either an urticarial or an exanthematous drug eruption. Up to 5% of patients who receive certain antibiotics while hospitalized experience either urticarial or exanthematous reactions. During hospital admission 10% to 20% of patients have a drug reaction, and they represent the fifth most common cause of death in hospital.

When a combination of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is given to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients a hypersensitivity reaction may develop in as many as 50%. The risk of severe drug eruptions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is increased in HIV-positive patients and also in SLE, allo/BMT patients, and other immune dysregulated/immune abnormal states. Fatal anaphylaxis from intramuscular penicillin and fatal anaphylactoid reactions from radiocontrast each occur in about 1:50,000 exposed patients. In hospitalized children, cutaneous eruptions are the most common type of drug reaction seen. Around 2.5% of children receiving medication in the outpatient setting will experience a drug eruption, and this figure rises to 12% if the drug is an antibiotic.

Drug-Induced Skin Injury

The International Serious Adverse Event Consortium in collaboration with other stakeholders initiated the Phenotype Standardization Project. The goal was to develop standardized phenotypic definitions for three types of ADRs including cutaneous reactions caused by drugs: “drug-induced skin injury” (DISI). While the majority of DISIs are mild, the more serious entities including drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), which is also known as drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), SJS/TEN, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) form a more complex scenario within which genetics are an emerging factor.

Approach to the Patient with a Suspected Drug Eruption

Making the correct diagnosis is a vital element in the assessment process of possible CADRs prior to introducing treatment or recommendations. Diagnosis can be difficult because drug eruptions can closely mimic other diseases (e.g., exanthematous drug reaction vs. a viral exanthem, toxin-mediated erythema, or acute graft-versus-host disease, and AGEP vs. pustular psoriasis). Identification of the causative drug can be complicated if the patient is taking several different drugs concomitantly. For accurate diagnosis a rational approach is required. This includes an initial clinical impression, forming a differential diagnosis, analysis of drug exposure (including timing of new medications, dose adjustments or increases, drug–drug interactions, and metabolic changes and their impacts on drug levels, such as renal or hepatic insufficiency), laboratory results, diagnostic tests, and utilization of the available literature. Prioritization of the diagnosis includes a causality assessment.

An initial clinical impression is based principally on the morphology of the eruption. The four main categories described, based on the primary lesion, are exanthematous, urticarial, blistering, or pustular. Systemic signs (e.g., malaise, fever, hypotension, tachycardia, lymphadenopathy, synovitis, dyspnea, etc.) allow for refinement of the primary clinical impression ( Table 47-1 ). These systemic signs may aid in differentiating a benign or simple cutaneous drug eruption from a severe or complex drug eruption ( Table 47-2 ). Establishment of the diagnosis is the final step in diagnosis. Table 47-3 identifies the target organs potentially involved in complex reactions.

| Type of Eruption | Morphology | Mucous Membrane Involvement | Time to Onset | Common Implicated Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exanthematous | Erythematous | Absent | 4–14 days | Penicillins, sulfonamides |

| No blistering | Anticonvulsants | |||

| Generalized | ||||

| Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms | Severe exanthematous rash | Infrequent | 2–8 weeks | Anticonvulsants |

| Facial involvement | Sulfonamides | |||

| Edema | Allopurinol | |||

| Minocycline | ||||

| Urticaria | Wheals | Absent | Minutes to hours | Penicillins, opiates |

| Pruritus | Aspirin/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | |||

| Sulfonamides | ||||

| Radiocontrast media | ||||

| Angioedema | Swollen deep derma and subcutaneous tissue | Present or absent | Minutes to hours | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Aspirin | ||||

| NSAIDs | ||||

| Acneiform | Inflammatory lesions | Absent | Variable | Iodides, isoniazid |

| No comedones | Corticosteroids | |||

| Atypical sites | Androgens | |||

| Lithium, phenytoin | ||||

| Epidermal growth factor-receptor inhibitors | ||||

| Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis | Nonfollicular, sterile pustules arising on background of edematous erythema | Present or absent | <4 days | β-Lactam antibiotics |

| Macrolides | ||||

| Other antimicrobial agents | ||||

| Calcium channel blockers | ||||

| Rarely radiocontrast dye or dialysates | ||||

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | Atypical targets | Present | 1–3 weeks | Anticonvulsants |

| Mucosal inflammation | Sulfonamides | |||

| <10% body surface area | Allopurinol | |||

| NSAIDs | ||||

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Confluent and extensive epidermal detachment | Present | 1–3 weeks | Anticonvulsants |

| >30% body surface area | Sulfonamides | |||

| Allopurinol | ||||

| NSAIDs | ||||

| Fixed drug eruption | One or more round, well-circumscribed erythematous edematous plaques | Absent | First exposure: 1–2 weeks | Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole |

| Sometimes central bullae | Reexposure: <48 hours, usually within 24 hours | NSAIDs | ||

| Tetracyclines | ||||

| Pseudoephedrine |

| Exanthematous | |

| Simple | Exanthematous drug eruption |

| Complex | Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| Urticarial | |

| Simple | Urticaria |

| Complex | Serum sickness-like reaction |

| Pustular | |

| Simple | Acneiform |

| Complex | Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis |

| Bullous | |

| Simple | Pseudoporphyria |

| Fixed drug eruption | |

| Complex | Drug-induced pemphigus |

| Drug-induced bullous pemphigoid | |

| Drug-induced linear immunoglobulin-A disease | |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Fixed drug eruption | Purpura (nonvasculitis) |

| Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis | Photosensitivity |

| Eruptions from biologic agents | Erythema nodosum |

| Drug-induced lupus | Lichenoid |

| Sweet’s syndrome | Alopecia |

| Vasculitis | Hirsutism |

| Warfarin-induced necrosis | Hyperpigmentation |

| Dermatomyositis | Systemic allergic contact dermatitis |

| Target | Types of Reaction |

|---|---|

| Upper airway | Anaphylaxis, anaphylactoid reactions |

| Cardiovascular system | Anaphylaxis, anaphylactoid reactions, erythroderma |

| Lung | Anaphylaxis, anaphylactoid reactions, TEN, vasculitis |

| Liver | Drug hypersensitivity syndrome/Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| Kidney | Vasculitis, serum sickness, TEN, drug hypersensitivity syndrome |

| Gastrointestinal system | Vasculitis, TEN |

| Skin (burn-like complications) | SJS/TEN, pemphigus, pemphigoid, severe photosensitivity (sepsis, fluid/electrolyte abnormalities) |

| Mucosa (eyes, mouth, genital) | SJS/TEN |

| Thyroid | Drug hypersensitivity syndrome |

A careful analysis of drug exposure should ensue. All medications should be included, regardless of route of administration, and incorporate prescription drugs, over-the-counter, and herbal remedies. Patients or caregivers should be asked specifically about vitamins, pain medications, sedatives, laxatives, oral contraceptive pills, and any medications that may not be on a pharmacy list (e.g., infliximab, radiocontrast dye). In the Boston collaborative drug study most cutaneous reactions occurred after the first week of exposure. The onset of the cutaneous reaction should be carefully documented as well as the effect of previous patient-initiated rechallenge and dechallenge. Each drug, its dose, and duration along with relevant signs and symptoms should also be recorded.

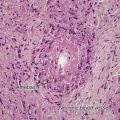

A literature search may provide helpful information. Laboratory tests can aid a diagnosis. A complete blood count and differential, liver and renal function should be requested. Cutaneous biopsies can be useful to differentiate between differential diagnoses but biopsies do not allow for confirmation of a causative drug. Histopathologic findings may help clarify the drug reaction pattern, but they do not identify the responsible drug. Histopathologic examination can confirm the diagnosis of SJS, fixed drug eruption, vasculitis, and erythroderma, and may support the clinical diagnosis of urticarial or morbilliform drug reactions. Eosinophils are widely believed to be major participants in many cutaneous drug reactions. The microscopic presence of eosinophils certainly suggests a drug cause; however, the absence of eosinophils does not exclude a drug as a possible etiologic agent nor does the presence of eosinophils confirm a drug as a possible etiologic agent.

There is no single diagnostic test that can be employed across the board in cases of cutaneous drug hypersensitivity. This is because of the variability of pathogenetic mechanisms operating in the different morphologic variants, the possibility that drug–virus interactions were important clinically, or that nonpharmacologic additives or excipients were responsible.

A list of available in vitro and in vivo diagnostic tests for drug hypersensitivity is found in Table 47-4 . In vitro testing includes lymphocyte transformation test, lymphocyte toxicity assay, histamine release test, basophil degranulation test, passive hemagglutination lymphocyte transformation test, leukocyte and macrophage migration inhibition factor tests, and radioallergosorbent test. Specific IgE assays, such as the radioallergosorbent test, are the most commonly employed for evaluating immediate hypersensitivity reactions. These include urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis. Only a few drugs can be tested this way, such as the β-lactams and insulin. Although IgE assays are still less sensitive than scratch tests, they should be used together with scratch testing under proper supervision in patients at risk for anaphylaxis. The basophil activation test uses flow cytometry to detect markers of response to drug allergens. It has been employed in cases of immediate hypersensitivity to β-lactams, muscle relaxants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

| In vitro Tests |

| IgE assays: radioallergosorbent test, immunoenzymatic assays |

| Basophil activation test |

| Lymphocyte transformation test |

| Lymphocyte activation test |

| In vivo Tests (Caution—Testing by Experienced Personnel in an Appropriate Clinical Setting) |

| Prick, scratch, or intradermal skin tests |

| Epicutaneous patch test |

| Histopathologic examination |

| Rechallenge/provocation |

The lymphocyte transformation test measures the proliferative response of a patient’s T cells in vitro to a suspected drug culprit. It has been reported to be more sensitive for diagnosis than patch testing, but has some limitations. First, although it has been found to be positive in the majority of cases of exanthematous reactions, the drug hypersensitivity syndrome, and AGEP, it is only rarely positive in cases of TEN, fixed drug eruption, and vasculitis. Second, timing of the test is important, with cases of the drug hypersensitivity syndrome showing a negative test in the first few weeks after onset of the eruption. Finally, the test is not available at most clinical centers.

In vivo tests include skin testing and provocation or oral rechallenge and also patch testing. Prick tests have been found to be a useful diagnostic tool in cases of sensitivity to β-lactams and muscle relaxants used in anesthesia. Intradermal testing can be performed when prick tests are negative. To date, penicillin is the most widely used systemic drug for which intradermal skin testing is significantly reliable. Patients with the majority of important drug reactions, including SJS and TEN, exanthematous reactions, vasculitis, and erythroderma, should not undergo this form of testing.

Patch testing for cutaneous drug reactions has been studied the most vigorously of all the skin tests. Sensitivity varies depending on the type of reaction, the putative drug, the concentration of drug tested, and, for fixed drug eruptions, the site at which the patch is placed. Positive results have been obtained in cases of exanthematous reactions, fixed drug eruption, AGEP, and the drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Sensitivity has varied between 30% and 50%. The specificity and negative predictive value have not been determined.

Establishment of the final diagnosis is the final step in the diagnosis. If a definite diagnosis is not possible then a prioritization diagnosis must be completed by combining the information gathered. The traditional approach of highly probable, probable, possible, unlikely, and almost excluded are helpful. The Naranjo assessment classifies a drug reaction as definite, probable, and possible. To fulfill the criteria for a definite reaction four components must be met. These include (1) temporal relationship, (2) a recognized response to the suspected drug, (3) improvement after drug withdrawal, and (4) reaction on rechallenge. A probable reaction includes parts 1 to 3 but does not include rechallenge and a possible reaction only requires a temporal relationship.

Discontinuation of drug therapy and resumption of therapy with the drug in question at a later time may allow immunologic effector mechanisms to “recharge” fully, making large-scale discontinuation of all drugs the patient is receiving worthy of careful scrutiny. The potential for the disease being treated to worsen after drug discontinuation has to be considered in dechallenge decisions. Each case should be handled individually, with a consideration of the risks and benefits of discontinuing drug therapy. In managing patients with high-risk reaction patterns, rechallenge with the drug in question should be carried out only in very rare circumstances, when the need to know the responsible drug exceeds the risk of a severe reaction with the rechallenge. Intentional rechallenge can be performed only when a clinical presentation meets the criteria in Table 47-5 . Reports of patients with accidental rechallenge provide useful information on drug causes, but it is essential to avoid such accidental rechallenge. It is important to note that rechallenge is not optimally sensitive or specific. Despite these limitations, rechallenge, when indicated, is the best way to identify accurately the causative drug in the clinical setting. The presence or absence of drug–drug and drug–virus interactions should always be considered in this diagnostic step.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree