Connective Tissue Disease and Vasculitis-Related Dermatoses

Stephanie Hu

Peter C. Schalock

Autoimmunity is the state of the immune system erroneously attacking self—antigens such as cellular DNA or dermal collagen. The diseases caused by this state are dependent upon the target antigen and the antibody(s) involved. In the case of immune-related dermatoses, some primarily affect the skin, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus or capillaritis/small vessel vasculitis. Others involve the skin secondarily to other systemic disease (e.g., systemic lupus, dermatomyositis). Vasculitis as a topic is exceedingly broad. Causes range from infections to autoimmune disease to systemic hypersensitivity reactions. In this chapter, the discussion of vasculitis will be limited to Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

|

A 21-year-old woman presents with diffuse polyarticular arthralgias, unable to walk due to pain, hematuria, proteinuria, severe mouth/tongue pain, and striking macular erythema on the central face/cheeks with sparing of the upper eyelids (Fig. 26-1). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is 102, antinuclear antibody (ANA) reveals a 1:2,320 positive with speckled pattern, and the double-stranded DNA test is positive. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Background/Epidemiology

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a serious multi-system disease arising from polyclonal B-cell autoimmunity, which involves connective tissue and blood vessels. The age of onset of SLE is typically around age 30 in females and age 40 in males. The disease is more common in women (with a female to male ratio of 8:1) and blacks, and less than 5% of patients report a positive family history of SLE. An SLE syndrome can be induced by drugs (i.e., hydralazine, certain anticonvulsants and antibiotics, and procainamide), but rash is a relatively uncommon feature of drug-induced SLE. Clinical manifestations of SLE include fever (90%); fatigue (100%); weight loss; malaise; skin lesions (85%); arthralgia or arthritis; abdominal pain; and CNS, renal, cardiac, and pulmonary disease.

Pathogenesis

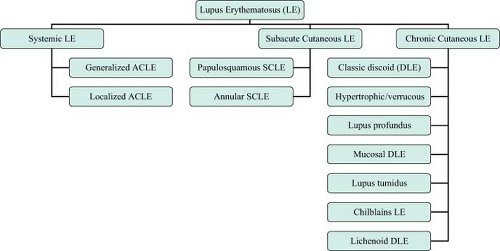

Lupus erythematosus (LE) encompasses a spectrum of diseases that share systemic clinical findings and distinct patterns of cellular and humoral autoimmunity. Skin lesions that are directly related to the LE autoimmune process can

be divided into LE-specific skin disease and LE–nonspecific skin disease. Within the LE-specific skin diseases, three clinical subtypes exist: acute cutaneous LE (ACLE); subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE); and chronic cutaneous LE (CCLE, also known as discoid LE or DLE) (see Figure 26-2 for classification). Some forms of LE-specific skin disease (i.e., ACLE) often occur in the clinical context of active underlying SLE, whereas other forms are usually associated with only mild or minor degrees of SLE activity (i.e., SCLE) or no SLE activity at all (i.e., CCLE, with localized DLE being the most common variety).

be divided into LE-specific skin disease and LE–nonspecific skin disease. Within the LE-specific skin diseases, three clinical subtypes exist: acute cutaneous LE (ACLE); subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE); and chronic cutaneous LE (CCLE, also known as discoid LE or DLE) (see Figure 26-2 for classification). Some forms of LE-specific skin disease (i.e., ACLE) often occur in the clinical context of active underlying SLE, whereas other forms are usually associated with only mild or minor degrees of SLE activity (i.e., SCLE) or no SLE activity at all (i.e., CCLE, with localized DLE being the most common variety).

Key Features

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a serious multi-system disease arising from polyclonal B-cell autoimmunity.

SLE syndrome can be induced by drugs (i.e., hydralazine, certain anticonvulsants and antibiotics, and procainamide).

Clinical manifestations of SLE include fever (90%); fatigue (100%); weight loss; malaise; skin lesions (85%); arthralgia or arthritis; abdominal pain; and central nervous system (CNS), renal, cardiac, and pulmonary disease.

The butterfly rash is the classic acute cutaneous finding in SLE. It is characterized by erythema in a sharply-defined malar distribution over the cheeks and bridge of the nose that appears in approximately one-half of patients, usually after UV exposure.

Treatment is with topical and oral corticosteroids, antimalarials, and in severe cases immunosuppressives such as azathioprine.

Clinical Presentation

Skin and mucous membranes are symptomatically involved at some point in over 80% of patients with SLE, although there is great variability and diversity in the type of involvement. Lesions in ACLE are typically precipitated by sunlight and are present for several weeks. Such lesions include the butterfly rash (Fig. 26-1), or localized ACLE, which is an erythematous, confluent, macular eruption on the face. This rash may precede other symptoms of lupus by months or even years or may be accompanied by other symptoms and signs of acute SLE. It often recurs. Application of alcohol (found in many sunscreens)

can enhance the redness, due to vasodilation in the skin. The SLE rash or generalized ACLE, may also be observed, which manifests as erythematous, discrete, papular, or urticarial lesions on the face, dorsa of hands, arms, and the V of the neck (Fig. 26-3).

can enhance the redness, due to vasodilation in the skin. The SLE rash or generalized ACLE, may also be observed, which manifests as erythematous, discrete, papular, or urticarial lesions on the face, dorsa of hands, arms, and the V of the neck (Fig. 26-3).

Vasculitis is a rare but important feature of SLE. Finding a cutaneous vasculitis often occurs in conjunction with a disease flare and is considered a poor prognostic factor. Commonly seen manifestations include livedo reticularis, microinfarcts on digital tips, palpable purpura, and urticaria.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a distinct entity and is frequently, but not uniformly, associated with SLE. Lesions are often nonscarring, nonindurated, erythematous, and papulosquamous (psoriasis-like), and/or annular and occur in a symmetrical pattern (Fig. 26-4). A subset of SCLE which presents with erythematous, nonscaling indurated plaques is tumid lupus. Approximately 50% of affected patients have SLE, and about 10% of patients with SLE have this type of skin lesion. The male to female ratio is 4:1. Cytopenia, serositis, and the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are significantly less frequent among those with SCLE than SLE, while photosensitivity is nearly twice as prevalent in those with SCLE as those with SLE (86% vs. 46%, respectively). The prevalence of renal disease in those with SCLE and SLE are not significantly different. Anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies are often found in SCLE. Medications (Table 26-1) may be responsible for initiating or exacerbating the skin disease.

General photosensitivity develops in 60% to 100% of patients with SLE, in which patients develop a rash after exposure to the UVB radiation found in sunlight or fluorescent lights. Some patients are also sensitive to UVA (as from a photocopier), and may even be sensitive to the visible light spectrum. Glass protects individuals sensitive to UVB, but only partially protects those sensitive

to UVA. Blond, blue-eyed, fair-skinned individuals are much more photosensitive than brunettes or individuals with pigmented skin; the incidence is also great in those with anti-Ro antibodies.

to UVA. Blond, blue-eyed, fair-skinned individuals are much more photosensitive than brunettes or individuals with pigmented skin; the incidence is also great in those with anti-Ro antibodies.

Table 26-1 Medications Commonly Causing SCLE | |

|---|---|

|

Other cutaneous lesions in SLE include bullae, which can be hemorrhagic in acute flares; papules and scaly plaques as in SCLE; discoid plaques in CCLE, predominantly on the face, arms, and scalp; and erythematous, sometimes violaceous, slightly scaling, densely set and confluent papules on the dorsa of the finger, usually sparing the articular regions (different from dermatomyositis, in which the rash overlies joint regions). Palmar erythema, mostly on fingertips, nail fold telangiectasias, “palpable” purpura (vasculitis), and urticarial lesions with purpura (urticarial vasculitis) are also seen. These vascular lesions occur in approximately 50% of patients. Diffuse alopecia or discoid lesions with patchy alopecia may be present, occurring in a majority of patients with SLE at some time during their illness. In some cases, alopecia can precede other manifestations of lupus. Mucous membrane involvement occurs in 12% to 45% of patients with SLE. This may manifest in painless ulcers arising in purpuric necrotic lesions on the palate (80%), buccal mucosa, or gums, in characteristic discoid lesions with erythema, atrophy, and depigmentation of the lips, or in gingivitis that is more common in individuals with xerostomia. There is no apparent association between the presence of oral involvement and systemic activity; oral lesions may be the first sign of lupus.

Physical Findings

The butterfly rash is the classic acute cutaneous finding in SLE. It is characterized by erythema in a sharply defined malar distribution over the cheeks and bridge of the nose that appears in approximately one-half of patients, usually after UV exposure. Fine scaling, erosions (in acute flares), and crusts may be present. The involved skin feels warm and appears slightly edematous. Generalized ACLE may occur as erythematous, discrete, papular, or urticarial lesions on photodistributed areas of the body, including the face, dorsa of hands, arms, and the V of the neck.

SCLE lesions begin as small, erythematous, slightly scaly papules that evolve into either a psoriasiform (papulosquamous) or annular rash. The latter often coalesces to form polycyclic or figurative patterns. The lesions typically have erythematous, and sometimes crusted, margins. In contrast to CCLE/DLE, follicular plugging, hyperkeratosis, dermal atrophy, permanent pigment changes, and scarring do not occur, although telangiectasia may be seen. The most commonly affected areas in SCLE are those exposed to sunlight: the shoulders, forearms, neck, and upper torso, with frequent sparing of the face.

Subepidermal bullous skin lesions may occur as a result of toxic necrolysis of the skin. In addition, SLE is rarely associated with bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisitum.

Lichen planus (LP)-LE overlap syndrome is a rare skin disorder that demonstrates findings of both LE and LP. The cutaneous lesions consist of atrophic red to violaceous plaque and patches that are most often present on the acral portions of the extremities. The nails are commonly involved and there may be anonychia (absence of the nail). These lesions are persistent and resistant to treatment. Photosensitivity, pruritus, and follicular plugging (characteristics of discoid lupus) are generally absent. Some patients with this overlap develop SLE.

Nail lesions, particularly pitting, ridging, and onycholysis, have been noted in 25% of patients. About 20% of patients have redness of the lunula, a finding nearly always associated with periungual erythema.

Lupus alopecia may be scarring or nonscarring and can involve the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, beard, and/or body hair. Early lesions of scarring alopecia are characterized by well-circumscribed, erythematous, infiltrative patches with adherent follicular hyperkeratosis. Later, the lesion progresses toward an

atrophic, smooth, depressed, white–ivory-colored plaque. In nonscarring alopecia caused by premature hair loss (telogen effluvium), a diffuse thinning of the scalp is seen 3 months after a stressful event, emotional upset, pregnancy, or the use of glucocorticoids. During exacerbations of SLE the hair is thin, unruly, and easily fractures. It usually occurs along the frontal hairline and grows back normally when the disease activity subsides.

atrophic, smooth, depressed, white–ivory-colored plaque. In nonscarring alopecia caused by premature hair loss (telogen effluvium), a diffuse thinning of the scalp is seen 3 months after a stressful event, emotional upset, pregnancy, or the use of glucocorticoids. During exacerbations of SLE the hair is thin, unruly, and easily fractures. It usually occurs along the frontal hairline and grows back normally when the disease activity subsides.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical findings, histopathology of the skin biopsy specimen, the lupus band test using immunofluorescence, and serology within the framework of the revised American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria for classification of SLE (see Table 26-2). The lupus band test (LBT, direct immunofluorescence demonstrating IgG, IgM, and C3) is positive in lesional skin in 90% of patients, in clinically normal sun-exposed skin in 70% to 80% patients and in clinically normal non–sun-exposed skin in 50% of patients.

ANA is positive in greater than 95% of patients, with a peripheral pattern of nuclear fluorescence. Anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, anti-Sm antibodies, and rRNP antibodies are specific for SLE. Low levels of complement are seen, particularly in patients with renal involvement. Anticardiolipin autoantibodies

(lupus anticoagulant) are present in the specific subset of patients with the anticardiolipin syndrome, and anti-Ro/SS-A autoantibodies have a low specificity for SLE but are specific in the subset of patients with SCLE lesions.

(lupus anticoagulant) are present in the specific subset of patients with the anticardiolipin syndrome, and anti-Ro/SS-A autoantibodies have a low specificity for SLE but are specific in the subset of patients with SCLE lesions.

Table 26-2 ARA Criteria for Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hematologic findings in SLE include anemia (usually normocytic, normochromic, or rarely, hemolytic Coombs-positive); leukopenia (<4,000/μL); lymphopenia; thrombocytopenia; and elevated ESR (which can be a useful guide to monitoring disease activity). Urinalysis can demonstrate persistent hematuria, proteinuria, and casts with the development of lupus nephritis.

Therapy

General measures in the treatment of SLE include rest, avoidance of sun exposure and photosensitizing medications, and liberal use of daily sunscreen. A lupus rash should initially be treated with topical glucocorticoids. Hydrocortisone may suffice for early, superficial involvement, but more potent steroids (particularly the fluorinated preparations) should be used for thicker lesions.

Antimalarials are useful for treatment of the skin lesions in subacute and chronic LE but do not reduce the need for prednisone. Precautions need to be observed in its use; adverse events include precipitation of flares of psoriasis and porphyria cutanea tarda, hemolytic anemia in patients with G6PD deficiency and ocular changes such as macular degeneration. Currently, the most commonly used antimalarial in SLE is hydroxychloroquine, dosed by weight (less than 6.5 mg/kg per day to a maximum of 400 mg/day, and less than 400 mg/day for patients weighing less than 61 kg). Chloroquine 250 to 500 mg/day is somewhat more potent but has a higher risk of eye damage. Quinacrine 50 to 100 mg/day is even more effective and has a much lower risk of eye damage, but the skin turns yellow in many patients and bone marrow suppression is a rare complication. Improvement with antimalarials may not be seen until 6 to 12 weeks of use.

Indications for prednisone (60 mg/day in divided doses) include a) CNS involvement; b) renal involvement; c) severely ill patients without CNS involvement; d) hemolytic crisis; and e) thrombocytopenia. Concomitant immunosuppressive drugs, i.e., azathioprine or cyclophosphamide, can be added, with the choice of the agent depending on organ involvement and disease activity. In renal disease, intravenous cyclophosphamide bolus therapy may be beneficial. Systemic steroids and immunosuppressive agents are rarely needed to clear skin lesions except for bullous lesions, although local injections of resistant lesions with glucocorticoids may be effective for resistant skin lesions.

Hair loss in active SLE usually responds well to treatment of the lupus, while hair loss due to glucocorticoids recovers as the steroid dose is lowered. The hair loss is usually permanent when associated with scarring, as with discoid lesions of the scalp. Intralesional triamcinolone injection (3 to 10 mg/cc) may be useful for treatment of localized areas of alopecia, especially early in the course before scarring has occurred to a significant extent. Topical minoxidil may be beneficial in a limited number of patients with acute, nonscarring alopecia.

Mucous membrane lesions respond well to topical glucocorticoids (usually Orabase mixed with either 0.1% triamcinolone or 0.05% clobetasol), 0.1% tacrolimus ointment, intralesional glucocorticoids, and systemic antimalarial drugs. The response to topical steroids takes a few days to weeks, while the response to hydroxychloroquine takes weeks to months.

In the acute stages of disease, patients with systemic lupus are managed by a team consisting of primary care providers, rheumatologists, and other appropriate specialists such as dermatologists or nephrologists.

For stable patients, often primary care providers provide continuing care.

“At a Glance” Treatment

General Measures:

Rest, avoidance of sun exposure and photosensitizing medications, and liberal use of daily sunscreen.

Cutaneous SLE: initially treated with topical glucocorticoids:

Hydrocortisone 2.5% cream BID for early, superficial involvement

Clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream/ointment should be used for thicker lesions.

Oral prednisone (60 mg/day in divided doses) for:

a) CNS involvement, b) renal involvement, c) severely ill patients without CNS involvement, d) hemolytic crisis, and e) thrombocytopenia

Antimalarials treat skin lesions in subacute and chronic LE but do not reduce the need for prednisone for systemic therapy:

Hydroxychloroquine, dosed by weight (less than 6.5 mg/kg per day to a maximum of 400 mg/day, and less than 400 mg/day for patients weighing less than 61 kg).

Chloroquine 250 to 500 mg/day is somewhat more potent but has a higher risk of eye damage.

Quinacrine 50 to 100 mg/day is even more effective and has a much lower risk of eye damage, but the skin turns yellow in many patients and bone marrow suppression is a rare complication.

Improvement with antimalarials may not be seen until 6 to 12 weeks of use.

Sun protection, both in the form of sun avoidance and sun protection, is mandatory for all lupus patients. Sunlight exposure alone may activate cutaneous or systemic lupus.

Course and Complications

The 5-year survival rate for SLE is currently 93% and has increased dramatically over the last several decades due to increased disease recognition with more sensitive diagnostic tests, earlier diagnosis or treatment, the inclusion of milder cases, and increasingly judicious therapy and prompt treatment of complications. Most patients have a relapsing and remitting course, which may be associated with the use of high-dose steroids during the treatment of severe flares.

Factors that may be associated with a shorter delay between disease onset and organ damage include Hispanic ethnicity, greater disease activity, a history of thrombotic events, and glucocorticoid use of less than 10 mg per day.

ICD9 Code

| 710.0 | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Chronic Cutaneous Lupus

Stephanie Hu

|

A 47-year-old woman presents with the complaint of hair loss. She reports having slowly progressive hair loss associated with focal erythematous, scaling plaques in her scalp (Fig. 26-5). She has also had similar lesions on her skin which were slightly pruritic. They healed spontaneously after months to years with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. What is her diagnosis and what is the best therapy to initiate?

Background/Epidemiology

Chronic discoid lesions develop in up to 25% of patients with SLE but may also occur in the absence of any other clinical feature of SLE. Patients with only cutaneous discoid lupus generally have a negative or low-titer antinuclear antibody (ANA), and rarely have low titers of anti-Ro antibodies. Patients with cutaneous discoid lupus have approximately 5% to 10% risk of eventually developing SLE, which tends to be mild. Patients with more numerous and widespread lesions appear to be more likely to develop SLE. The disease is possibly more severe in Africans or African Americans. DLE lesions can be precipitated by sunlight, but to a

lesser extent than ACLE or SCLE. Lesions last for months to years and are usually asymptomatic, although they can sometimes be slightly pruritic or painful.

lesser extent than ACLE or SCLE. Lesions last for months to years and are usually asymptomatic, although they can sometimes be slightly pruritic or painful.

Key Features

Chronic discoid lesions develop in up to 25% of patients with SLE but may often occur in the absence of any other clinical feature of SLE.

Classic CCLE/DLE lesions may be treated with potent topical glucocorticoids, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection or oral antimalarials.

Less common cutaneous lesions of CCLE include lupus panniculitis/profundus, lupus tumidus, and chilblains (pernio). Patients with lupus panniculitis/profundus present with firm, circumscribed subcutaneous nodules that occur before or following the typical lesions of DLE but also in their absence. Some patients with lupus panniculitis/profundus exhibit no other manifestations of SLE; only 10% to 25% of such patients eventually develop SLE.

Lupus tumidus is a rare variant of CCLE/DLE. Patients are photosensitive and generally lack ANA, and it is rare for patients presenting with this form of cutaneous LE to develop clinically significant SLE later.

Chilblains lesions (pernio) can occur as a benign isolated clinical phenomenon (idiopathic chilblains) or as a cutaneous manifestation of an evolving underlying autoimmune disease such as LE (i.e., chilblains LE). Lesions tend to occur after cold exposure. Patients having chilblains associated with SLE are more often female and tend to exhibit persistent lesions beyond the cold season. Lesions resemble old lesions of DLE both histologically and clinically, and most patients with this variant have Raynaud phenomenon and DLE elsewhere; individuals presenting with chilblains skin lesions should be carefully evaluated and followed for the development of SLE.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of CCLE is the same as that of all types of lupus. See the SLE section for a detailed discussion.

Clinical Presentation

Discoid lesions are characterized by brightly erythematous papules that evolve into discrete, slightly infiltrated plaques covered by a well-formed adherent scale that extends into dilated hair follicles (follicular plugging). Scales are difficult to remove and show spines (upon magnification) on the undersurface resembling carpet tacks. Discoid lesions are most often seen on the face, neck, and scalp, but also occur on the ears, dorsa of forearms, hands, fingers, toes, and infrequently on the upper torso. They tend to slowly expand with active inflammation at the periphery, and then to heal, leaving depressed central scars, atrophy, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation/depigmentation. Some discoid lesions are hyperkeratotic. Scarring alopecia can be seen with residual inflammation and follicular plugging (Fig. 26-5).

Lupus panniculitis/profundus manifests as a firm, nodular lesion or a platelike infiltration with or without an overlying surface cutaneous lesion. The nodules, which are often painful and may be better felt than seen, may appear on the scalp, face, arms, chest (especially the breasts), back, thighs, and buttocks. The nodules usually resolve but may leave a depressed area. Subcutaneous calcification can result, which may produce considerable disability from secondary overlying cutaneous ulceration and infection.

Lupus tumidus is a rare variant of CCLE/DLE characterized by photodistributed, succulent lesions consisting of chronic pink to violaceous papules, nonscarring urticarial plaques, and/or nodules, in the absence of surface changes (i.e., overlying scale or follicular hyperkeratosis), which is in contrast to classic DLE lesions. They typically present over the face, neck, upper trunk, and proximal upper extremities.

Chilblains skin lesions (pernio) are cold-induced violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques typically distributed over the face and acral aspects of the extremities. As these lesions evolve, they usually assume the appearance of scarred atrophic plaques with associated telangiectasia; persistent lesions can develop a verrucous surface change.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CCLE lesions requires correlation of clinical and histopathological findings. Immunofluorescence in the form of the lupus band test is positive in 90% of active lesions at least 6 weeks old and not recently treated with topical glucocorticoids. The lupus band test is negative in burned-out (scarred) lesions and in the normal skin, both sun-exposed and nonexposed. Serology may show a low incidence of ANA in a titer greater than 1:16. Patients are also occasionally leukopenic with white blood cell counts of typically less than 4,500/μL.

Therapy

Classic CCLE/DLE lesions may be treated with topical glucocorticoids. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, 3 to 10 mg/mL, may also be injected. Administration of antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine, equal to or less than 6.5 mg/kg body weight per day, is another option. If this is ineffective, quinacrine, 100 mg TID may be added. Appropriate ophthalmologic evaluation is needed for patients on antimalarial agents. Hyperkeratotic DLE lesions respond well to systemic acitretin at 1 mg/kg body weight. Topical sunscreens (SPF >45 with broad UVA coverage) should be used routinely to prevent further development of lesions.

Lupus panniculitis/profundus may be treated with antimalarials or a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. Lupus tumidus also responds to antimalarial therapy.

Newer treatments showing promise in the treatment of chronic LE include mycophenolate mofetil, anti-TNF therapy, thalidomide, B-cell targeted therapy (i.e., rituximab, epratuzumab), and costimulatory blockade (i.e., abatacept and leflunomide).

“At a Glance” Treatment

CCLE/DLE/tumid lupus lesions:

Topical corticosteroids: clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream/ointment BID to AA for nonfacial/genital skin

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, 3 to 10 mg/mL

Hydroxychloroquine, equal to or less than 6.5 mg/kg body weight per day, quinacrine, 100 mg TID may be added as necessary:

Appropriate ophthalmologic evaluation is needed for patients on antimalarial agents. Hyperkeratotic DLE: acitretin at 1 mg/kg body weight.

Topical sunscreens (SPF >45 with broad UVA coverage) are essential

Patients with recalcitrant symptomatic lesions may benefit from a dermatology consultation. For those with symptoms suggestive of transformation to active systemic lupus, a rheumatology consultation may facilitate further diagnosis and care.

Sun protection and sunscreen is essential for preventing new lesions and progression of established lesions.

Course and Complications

Overall, only 1% to 5% of patients with CCLE develop SLE. With localized lesions, complete remission occurs in 50% of patients, whereas remission is less frequent (<10%) with generalized lesions. CCLE lesions may be the presenting cutaneous sign of SLE.

ICD9 Code

| 695.4 | Lupus erythematosus |

Dermatomyositis

Stephanie Hu

|

A 52-year-old woman presents for a recalcitrant facial, eyelid, and hand dermatitis (Figs. 26-6, 26-7) that has been present for several months. She has never had a similar rash in the past, is not atopic. She is feeling well other than a vague complaint of abdominal enlargement. On further questioning, she reports having new onset problems standing up from a chair and with combing her hair. What is the most likely diagnosis? What further screening exams should be performed?

Background/Epidemiology

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a systemic disease classified with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, a heterogeneous group of genetically determined autoimmune diseases targeting the skin and/or skeletal muscles. Defined clinically, the prevalence rate of DM is estimated at approximately one per 100,000 in the general population. There is a female to male predominance of about 2:1. Although the peak incidence in adults occurs between the ages of 50 and 60, individuals of any age may be affected, and both juvenile and adult (>40 years) onset variants of the disease have been described.

Pathogenesis

The etiology of DM remains unknown. The disease is considered to be a humorally mediated disorder in which the cellular infiltrate, located principally in perifascicular regions of muscle, is often focused around blood vessels. The inflammatory infiltrate is composed of B cells and plasmacytoid CD4+dendritic cells. Other typical features include perifascicular atrophy and fibrosis. Abnormal muscle fibers are usually grouped in one portion of the fascicle, suggestive of microinfarction mediated by blood vessel dysfunction. Drug-induced DM is uncommon, but hydroxyurea is the most frequently implicated agent.

Key Features

Dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy commonly involving skin and muscle.

Pathogenesis is unknown. Drug-induced DM is uncommon. In some cases, this is a paraneoplastic condition.

This is most commonly a disease of adults, but juvenile variants exist (which are not paraneoplastic in etiology).

Diagnosis is through characteristic skin biopsies and serologies including an anti-Jo1, anti-SRP and anti-Mi2 antibody.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree