Conjoined Twin Separation

Michael R. Bykowski

Joseph E. Losee

Lorelei Grunwaldt

DEFINITION

Conjoined twins are individuals who are physically connected by their anatomy and share one or more organs. The site of fusion and orientation of the twins characterize the different types of conjoined twins. Although some conjoined twins can live functional lives, surgical separation is often performed for religious beliefs, cultural beliefs, parental wishes, and/or to promote survival of one or both twins.

Conjoined twin separation is the procedure of surgically dividing the conjoined twins, allocation and reconstruction of shared organs, and soft tissue coverage. The challenge of the complex anatomy and physiology requires comprehensive preoperative planning and coordination by a multidisciplinary team often lead by the plastic surgeon.

Because there is great variability of fusion patterns of conjoined twins, surgical management cannot be reliably predicted and is not amendable to treatment within fixed protocols. As such, this chapter discusses the general key principles for planning and executing separation of conjoined twins.

ANATOMY

The detailed anatomy of conjoined twins is dependent on each set of twins. In general, however, the larger the connecting bridge between twins, the more complex its contents.

The tissues of conjoined twins are normal but the anatomy is not. The anatomy is always abnormal but not in a reliably predictable manner. Nonetheless, there are general patterns to the anatomy based on the fusion type. The anatomical arrangements may be such that one twin may be incapable of independent existence.

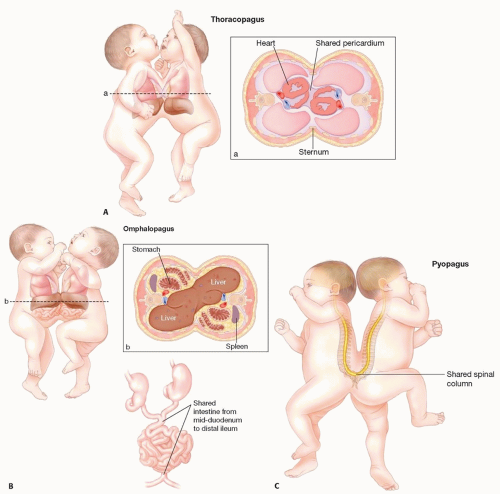

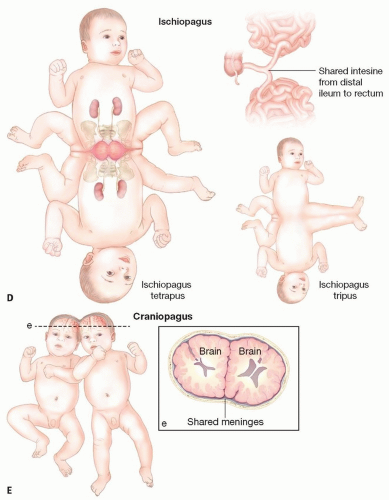

Classification is based on terminology according to the most prominent site of connection plus the suffix “pagus,” which is the Greek word meaning “that which is fixed”.1 Some forms are described below:

Thoracopagus (40 cases; FIG 1A): junction primarily at the chest with varying amount of fusion of the heart, pericardium, and diaphragm.

Omphalopagus (34 cases; FIG 1B): joined at the abdomen and often have fusion of the liver and gastrointestinal (GI) tracts.

Pygopagus (18 cases; FIG 1C): connection at the sacrum/perineum and commonly face away from each other. May have fusion of the terminal spinal cord and associated meninges.

Ischiopagus (6 cases; FIG 1D): connected at the pelvic level. Each twin may have a normal leg and a common fused leg (ischiopagus tripus) or each has two normal legs (ischiopagus tetrapus). Often have fusion of distal small intestine/large intestine and genitourinary system.

Craniopagus (2 cases; FIG 1E): fusion of the skull and meninges. (The separation of craniopagus twins is often driven by the neurosurgical team and is not discussed in detail in this chapter.)

PATHOGENESIS

Conjoined twins are monozygotic, monoamniotic, and monochorionic.

There are two leading theories for the pathogenesis of conjoined twin formation.2

Failure of separation of the embryonic plate approximately 15 to 17 days of gestation

Union of two separate embryonic discs

NATURAL HISTORY

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The minimal diagnostic criterion is the fusion of some portion of monozygotic twins.

The main physical finding—ie, the site at which the twins are connected—provides insight to the internal anatomy. Predictable patterns of fusion occur and are associated with shared organs and organ abnormalities (see FIG 1).

IMAGING

From the time of prenatal diagnosis to the time of surgical separation, imaging is the most important aspect of conjoined twin management.

Prenatal and postnatal imaging evaluations are critical for predicting prognosis, obstetrical planning, medical management, and ultimately surgical separation.

Conjoined twins can be first diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound by the 12th week of gestation.5

Specific diagnostic ultrasound findings include fixed position of the twin bodies on repeated examinations over time, lack of a separating membrane between the twins, and an inability to visualize a separation between the fetal bodies and skin contours.

Once the presence of conjoined twins is diagnosed prenatally, further imaging is crucial to delineate the anatomy and

extent of shared organs; both of which are important for obstetrical purposes and prognosis.

Due to the high incidence of cardiac abnormalities, fetal echocardiography is the most important prenatal evaluation.

All conjoined twins (irrespective of the site of connection, but especially for those with a ventral union pattern)4 should undergo fetal echocardiography.

The degree of cardiac fusion and the severity of associated cardiac anomalies can help predict the postnatal viability and thus provide information for parental counseling.

Prenatal computed tomography (CT) is useful to delineate the anatomic arrangement of the twins, primarily bony anatomy.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best modality to provide the most detailed imaging of the fetuses as well as their associated anomalies and extent of union.

Ultrafast T2-weighted MRI sequences eliminate the need for maternal sedation and allow precise anatomical assessment of fetal organs avoiding the artifact due to fetal movement.

Once the fetuses are determined to be viable and subsequently survive birth and the neonatal period, elective surgery can be planned with a team approach and with repeat postnatal imaging (discussed in detail below under “Preoperative Planning”).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Teratoma

Lymphatic malformation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

In determining operative vs nonoperative management of conjoined twins, a pragmatic approach is necessary to balance:

What is technically feasible by the health care team.

The parental wishes.

The likely outcome for the children with or without separation. (The issue of parental consent is beyond the scope of this chapter.) The technical feasibility and prognosis are issues that depend on each other and are dictated by which organs are connected and the extent of their connections.

An extreme example demonstrating successful nonoperative management of a set of conjoined twins is the famous Eng and Chang Bunker. These twins—born in Siam in 1811— gained notoriety while traveling with the Barnum & Bailey Circus under the exhibition name “Siamese Twins.” Despite their abdominal connection, Eng and Chang married sisters, fathered 22 children, and lived together for 63 years.

Separation of conjoined twins is contraindicated in the following circumstances:

Thoracopagus twins with complex cardiac fusion

Craniopagus twins with extensive cerebral fusion

Separation that would result in physical disability, which is unacceptable to the parents. This is often associated with shared organ systems with compromise of one or both twins when the organ system is removed from one twin (often seen in parapagus, extensive ischiopagus, and craniopagus).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The discussion of this chapter focuses on elective separation, but the management of conjoined twins can be characterized as three distinct groups:

Nonoperative

Emergency separation

Elective separation

The objective of the operation is to separate the conjoined twins while adequately allocating each individual with

organs for survival and to obtain soft tissue coverage over the resulting defect. In general, the anatomy of the junction and the shared organs and structures dictate the technical details of the procedure.

A multidisciplinary approach is required along with frequent planning meetings, involving all of the staff necessary before, during, and after surgical separation.

The staff should include nursing, neonatologists, pediatricians, critical care physicians, anesthesiologists, and a variety of surgical specialists. Because a critical factor in conjoined separation is soft tissue coverage, the plastic surgeon is often the team leader and coordinates all activity.

Elective separation should be delayed until at least 2 months of age if possible.6 The timing of separation varies widely from 2 months to 2 years of age. The critical factor is to allow time for extensive preoperative planning and simultaneous medical optimization.

Occasionally, conjoined twins require mechanical ventilation to preserve respiratory functioning toward the end of tissue expansion of the abdomen or thorax, as there may be decreased tidal volume from external compression.7

Due to the varied anatomy of conjoined twins, it is usually not possible to follow a predetermined protocol for surgical separation. In general, the main steps of the procedure are as follows:

Exposure of shared organs

Division, allocation, and reconstruction of shared organs

Identification and ligation of cross-circulation

Abdominal wall reconstruction and wound closure with rotational flaps, previously expanded tissues, and skin substitute materials

Preoperative Planning

Although the health care team is large and multidisciplinary, it must be clear that there is a lead surgeon who is in charge and makes the final decisions on preoperative evaluations and treatment.

Conjoined twin separation is technically challenging due to the various organs that can be fused. The most important factor for successful separation is preoperative planning through postnatal multimodal imaging modalities.

Postnatal imaging is the keystone of preoperative planning to, firstly, assess operability and, secondly, to understand the shared anatomy and help with surgical planning.

Three features are key to determining survival and thus should be a focus of preoperative planning:

Major vascular connections

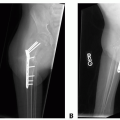

CT angiogram: this modality is necessary to visualize vascular connections.

Management of the body wall closure: without adequate soft tissue coverage, the patient is at risk for exposure of viscera, evisceration, and sepsis. CT imaging allows sufficient assessment of the anticipated soft tissue deficiency and can help determine reconstructive options. If closure is too tight, cardiac and pulmonary functioning can be compromised. Therefore, additional soft tissue coverage needs to be created or temporizing measures must be employed.

Tissue expansion.

Mesh or dermal substitutes.

Rotational flaps can be used as an adjunct to tissue expansion and skin substitutes.

Performance of both hearts after separation: cardiovascular performance after separation is not predictable given potential changes in cardiac functioning and changes in circulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree