Ambiguous Genitalia

Deborah L. Jacobson

Elizabeth B. Yerkes

DEFINITION

Individuals born with ambiguous genitalia have external genitalia that are not fully typical male or female in appearance. Others have developmental differences that are not externally apparent but may impact future function or well-being. These groups have some degree of discordance between genetic, gonadal, and phenotypic sexual characteristics.

Medical nomenclature used over the decades was well intentioned but has been viewed as pejorative. Accordingly, nomenclature with multiple subterminologies has evolved with the goal of correcting this situation.

Hermaphroditism, pseudohermaphroditism, intersex state/disorder, and disorders of sex development (DSD) have been used to describe the state of having ambiguous or nontypical genitalia with or without chromosomal or gonadal anomaly.

Even the most recent nomenclature, which originated from a consensus of experts, affected individuals, and advocates, is not uniformly accepted by the community. “Disorder” is not widely embraced as a desired description.

Whereas genital ambiguity and differences of sex development have historically been considered pathologic and in need of surgical correction, contemporary viewpoints acknowledge many phenotypic variations on the continuum of human genital development.

The authors understand that surgical reconstruction of ambiguous genitalia is a controversial topic and do not presuppose that surgical intervention is necessary for, or would be preferred by, any given individual.

This chapter will cover the technical aspects of genital reconstruction; however, surgical management should only be undertaken after extensive counseling and shared decision-making. Longitudinal multidisciplinary care for the individual and family is strongly encouraged.

This chapter will focus on feminizing genital procedures and the diagnoses that could involve decision-making for these types of procedures.

ANATOMY

Clitoris

The corpora cavernosa (erectile bodies) of the clitoris originate proximally as paired crura, swell medially to form the clitoral bulbs, and unite distally.

The paired cavernosa support a glans covered by a prepuce of labia minora. MRI imaging studies performed by O’Connell et al demonstrate that the glans lies caudal to the corporal bodies, leading to a natural hairpin curve.1

Autonomic input is via the paired cavernous nerves, which originate from the vaginal plexus at the 10 and 2 o’clock positions along the vagina and course dorsally along the proximal urethra.2 The nerves travel with the cavernous arteries and enter the clitoral bodies under the pubic arch.

Somatic supply is via the paired dorsal nerves of the clitoris, which originate from the pudendal nerves, run dorsolaterally along the crura and ischiopubic rami at approximately the 11 and 1 o’clock positions, and enter the glans at the corona. The nerves branch, fanning out along the clitoral bodies dorsally and laterally. Nerves are absent in the dorsal midline and deficient ventrally.

The cavernous arteries originate from the internal pudendal artery, travel with the cavernous nerves, and enter the clitoral body under the pubic arch. Dissection between the crura at the pubic arch should be avoided.

Variations from typical clitoral anatomy should be expected in patients with virilization of female genital tissue.

Labia

The labia majora embryologically correspond to the male scrotum. They are separated by the vulvar cleft, which contains the labia minora and clitoris. Together the structures conceal the vestibule.

The labia minora and urethral plate correspond to the male anterior urethra. The labia join superiorly to frame the glans clitoris as the clitoral hood.

Vagina

The vagina consists of a rugated mucous membrane fixed to a bilayered muscular invagination. It is suspended from the levator ani ventrally, the rectovaginal septum dorsally, and the cervix apically.

Arterial supply is via uterine, vaginal, and internal pudendal branches coursing along the anterolateral surface of the vagina.

Innervation originates anterolaterally via autonomic branches of the uterovaginal plexus and somatic branches of the pudendal nerve.

The ureters pass adjacent to the lateral margins of the vagina and insert into the base of the urinary bladder.

PATHOGENESIS

Cloacal development

The cloacal membrane folds with differential embryonic growth beginning in week 4, and the cloaca partitioned into anterior (urogenital sinus—UG sinus) and posterior (hindgut) compartments with the descent of the urorectal septum.

Disruption of normal cloacal development can lead to persistent cloaca or UG sinus anomalies.

Development of the external genitalia

Fetal androgenization leads to elongation of the genital tubercle, fusion of the urethral folds, and fusion of the labioscrotal folds.

Development of the abdominal wall

Failure of mesodermal ingrowth or premature rupture of the cloacal membrane leads to bladder or cloacal exstrophy.

Development of the UG sinus

Caudal paramesonephric (Müllerian) duct deficiencies may lead to agenesis of the proximal vagina and variable anatomy of the uterus/fallopian tubes (Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome).

Lateral paramesonephric (Müllerian) fusion anomalies may lead to uterus didelphys, bicornuate uterus, or unicornuate uterus.

Deficiency of the distal UG sinus may lead to vaginal atresia.

Incomplete vaginal canalization may lead to an imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of an individual in this population, or the population as a whole, is not entirely known.

For androgenized individuals, it is unclear what the prenatal hormonal milieu (both in terms of absolute androgen levels and the response of developing genital/nervous tissues) portends for future gender identity or sexuality.

For virilized females (such as patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia) in whom medical control is irregular, continued irreversible changes may occur in the genital tissues.

The psychosocial outcomes of early vs delayed surgery remain unclear, as does the definition and likelihood of surgical success.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Antenatal course: complications, history of prematurity, and other anomalies

Evidence of maternal exposure to endogenous or exogenous androgen

Severe acne, abnormal hair growth, clitoral enlargement, or Cushingoid appearance

Drugs, virilizing tumors, or adrenal disorders

Family history:

Known chromosomal anomalies

Fetal/neonatal demise

Genital ambiguity or urologic anomalies

Infertility or consanguinity

Physical examination

General: overall appearance, dysmorphic features, and general infant well-being

Spine: gross deformity or neurocutaneous marks

Anomalous findings may indicate genetic syndromes or fetal exposures.

Tethered cord or occult spinal cord anomalies are common with select diagnoses.

Abdomen: marked distention, hernias, suprapubic masses, and wall abnormalities

May indicate bladder outlet obstruction, hydrometrocolpos, or urinary ascites

Perineum

Labioscrotal folds: prominence, rugation, pigmentation, and presence of gonads

Clitorophallic structure: dorsal stretched length, glans width, and corporal consistency

Perineal orifices: number, location, and patency

Gonads: presence by palpation, location, and consistency

Palpable gonadal tissue suggests presence of at least some ipsilateral testicular tissue

IMAGING AND SPECIALIZED EXAMINATION

Modalities are employed selectively based upon clinical findings and the active differential diagnosis.

Ultrasonography: Evaluation of the adrenals, kidneys, ureters, bladder, Müllerian structures, and gonads

Dilation of genital ducts or duplications or unclear anatomy may lead to additional radiographic or operative investigations.

Genitography: Delineation of internal genitourinary anatomy

A Foley catheter or occlusive nipple is used to occlude the UG sinus orifice.

Retrograde administration of contrast material defines the proximal anatomy including sinus length and level of confluence.

The vaginal confluence may be missed if the system is not well distended.

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG)

The catheter may be advanced for VCUG after genitogram if indicated or if the sinus is not opacified. Vesicoureteral reflux and bladder anatomy is assessed during filling, at bladder capacity, during voiding, and after voiding is complete.

VCUG alone may not opacify the vagina, so it is less useful study for assessing the UG sinus.

Endoscopy: Direct visualization of patient anatomy

Because general anesthesia is required, endoscopy may be performed at the time of definitive reconstruction unless additional anatomic evaluation is required for surgical decision-making.

MRI: Delineation of pelvic anatomy and associated spinal anomalies

MRI often requires anesthesia in young children and would therefore be considered when other imaging studies are inconclusive.

Diagnostic laparoscopy: very selectively used in infancy if additional information required

Laparoscopy is utilized to clarify internal anatomy and gonadal characteristics.

Gonadal biopsy may be necessary in select cases.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

This list includes only conditions in which patients could potentially be candidates for feminizing procedures.

Differences in gonadal differentiation

Pure gonadal dysgenesis

Mixed gonadal dysgenesis

Ovotesticular DSD (previously “true hermaphroditism”)

Differences in androgenization

Adrenal sources

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (in 46 XX patients)

21-Hydroxylase deficiency

11β-Hydroxylase deficiency

3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency

17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency (late virilization in 46 XY phenotypic female)

Androgen-secreting tumor

Maternal sources

Drugs

Androgen-secreting tumor

Placental sources

Placental aromatase deficiency

Androgen receptor dysfunction

Variations in activity of androgen receptor in various tissues (46 XY patients)

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (external genitalia phenotypically female, lacking Müllerian structures due to intact MIS)

Partial androgen insensitivity (diverse external phenotype, degree of virilization at puberty and innate gender identity not predictable)

Differences in embryonic development

Persistent cloaca

Exstrophy-epispadias and cloacal exstrophy

Müllerian anomalies

Müllerian agenesis (Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome)

Vaginal atresia

Fusion anomalies

Vaginal duplication

Uterine duplication

Vaginal septum variations

Urogenital sinus anomalies

High vaginal confluence

Low vaginal confluence

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Create a multidisciplinary team incorporating experienced pediatric urologists/pediatric surgeons/pediatric gynecologists, endocrinologists, psychiatrists/psychologists, geneticists, and nurses/social support members to work with the parents and child to guide patient care. Consider formal ethics consultations when appropriate.

There is a broad spectrum of “normal” female external genitalia. Referring providers, parents, and patients may be reassured by education on range of “normal.” Appearance and future functionality are important to consider in the pediatric patient if surgery is requested.

The timing and indications for feminizing genital reconstruction are currently controversial, and there may be long-term consequences of both action and inaction in this arena.

Performing feminizing surgery in prepubertal children precludes autonomous self-determination in surgical decision-making and may lead to regret.

Consider the psychosocial consequences of genital ambiguity, and provide appropriate counseling for patient and parent.

Patients deserve long-term psychological support, with or without surgical intervention.

Extended support networks may be found both within the hospital and in the patient’s own community.

Discuss patient reproductive potential, optimizing patient sexual development and fertility when possible. Administration of androgens or estrogens may be recommended in longer term, depending on the underlying anatomy and function.

Consider the potential for gonadal malignancy, which varies significantly with gonadal histology and patient pathophysiology. Whenever possible, gonadal preservation should be considered.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Diagnostic laboratory evaluation may include karyotype, serum electrolytes, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Additional adrenal and sex hormone testing is used more selectively but is essential to make a diagnosis in some cases.

A thorough examination under anesthesia should be completed, including inspection of external genitalia, palpation for gonads, cystoscopy, vaginoscopy (if applicable), and genitography.

Consider the need for gonadal biopsy or gonadectomy at the time of intervention, along with possible gonad cryopreservation.

Patients undergoing vaginoplasty require bowel preparation (enema vs polyethylene glycol solution) prior to surgical intervention.

Positioning

Isolated genitoplasty with or without repair of a low UG sinus is generally performed in frog-leg (infants, young children) or dorsal lithotomy (older patients) position with padding of all pressure points.

For reconstruction of a high UG sinus, most patients will require both prone and supine positioning, so total lower body preparation is utilized. This preparation may be advantageous in infants and young children for sterility of the field, whether high or low confluence.

Ensure there are no IVs in lower extremities.

A single-shot caudal block is reasonable in eligible patients, but a continuous caudal catheter is not utilized intraoperatively.

After endoscopy and catheter placement, keep the catheters sterile and move the patient up the table for second prep. Prep the lower body circumferentially from the xiphoid to the toes.

Place feet and legs in a stockinette.

Drape to allow for lower body repositioning from supine to prone within the drape (FIG 1).

Position the patient with stacked towels under the pelvis. Initial prone vs supine positioning will depend upon the planned procedures.

Approach

Primary components of the feminizing genitoplasty include the following:

Clitoral degloving

Elevation of the urethral plate and mobilization of the common UG sinus

Clitoral reduction

Urogenital sinus reconstruction and vaginoplasty

Creation of a clitoral hood and labioplasty

Several clitoral reduction techniques are utilized in contemporary feminizing genitoplasty.

Each is performed with attention to clitoral nerve sparing.

The timing of reconstruction elements is controversial.

“Early” single-stage reconstruction of the genitalia and UG sinus is performed with the goal of no additional procedures and no memory of the recovery. Additionally, the excess UG sinus tissue and genital skin can be redistributed as needed if the procedure is completed in a single stage. Despite these potential advantages, the smaller caliber of the infant vagina may increase the risk of vaginal stenosis and the likelihood of secondary procedures. Routine postoperative vaginal dilations are not recommended in this age group.

“Late” reconstruction preserves autonomous self-determination and allows the full advantage of virgin planes and tissues.

There may be limited options for positioning older patients.

Vaginal dilations will be required postoperatively, whether by medical grade dilators or sexual activity, so emotional maturity and commitment to outcomes are essential.

A staged reconstruction, by deferring either genitoplasty or vaginoplasty, precommits to two operative events and limits the redistribution of healthy tissues. The second stage may involve previously operated tissues.

The operative approach varies based on:

The surgical components to be included

The level of vaginal confluence in the UG sinus (“high” vs “low”)

The degree of virilization

TECHNIQUES

▪ Feminizing Genitoplasty: Examination

If repair of the UG sinus (urethroplasty and vaginoplasty) will occur:

Examination under anesthesia and endoscopy is performed in the dorsal lithotomy position to define UG sinus anatomy and denote the relative positions of the urethra and vagina.

A Fogarty catheter is inserted into the vagina and clamped. A Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder and periodically drained.

Alternatively, a Councill tip Foley catheter may be introduced into the vagina over a wire after emptying the bladder. Once the confluence of urethra and vagina is identified surgically, the catheter is redirected to the bladder.

A sponge may be placed into the rectum to allow for intraoperative palpation of the anterior rectal wall.

If repair of the UG sinus will not occur:

Examination under anesthesia is performed.

A Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder and periodically drained.

▪ Contemporary Nerve Sparing Clitoral Degloving

Blunt lysis of adhesions between the glans clitoris and inner prepuce is performed.

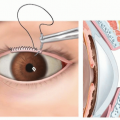

A retraction suture is placed through the dorsal midline of the glans (TECH FIG 1A).

The skin is retracted to expose the inner prepuce. A dorsal degloving incision is made more proximally than a standard circumcising incision to preserve preputial tissue for glans coverage as the inner layer of the clitoral hood (TECH FIG 1B).

Placement of the ventral degloving incision varies with the degree of virilization and intended procedure.

When the UG sinus meatus is found on the glans clitoris, the ventral degloving incision is immediately beneath the corona.

When the UG sinus meatus is located proximal to the glans clitoris, the ventral degloving incision begins immediately proximal to the orifice and extends distally to flank the urethral plate (TECH FIG 1C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree