Abstract

This chapter looks at the various ways of correcting contour irregularities of the abdominal wall. Matters to be determined in the presurgical exam (degree/extent of adiposity, redundant skin, laxity of musculofascial units, etc.) are reviewed, and surgical options for every finding are discussed. Treatment options fall under two broad categories: complete/full abdominoplasty and mini-abdominoplasty; liposuction is also an option for contouring the upper abdomen and flanks. A thorough discussion of each major option lays out all techniques, contingencies, and options. Important information on postoperative care is provided, along with advice on potential complications.

44 Abdominoplasty

44.1 Goals and Objectives

Understand the proper evaluation of prospective abdominal contouring patients.

Clearly define the indications for the various type of excision contouring procedures of the abdominal wall.

Appreciate the technical aspects of addressing each anatomic component of the abdominal wall required for proper contouring.

Know the evidence-based perioperative care to maximize patient safety and quality outcomes.

44.2 Patient Presentation

Patients with contour irregularities of the abdominal wall present with varied histories and physical findings. Some patients have had a massive weight loss from bariatric surgery or nonsurgical efforts. Others have had more modest weight loss, while many have had changes of weight and skin quality related to aging, pregnancy, and surgery. Accordingly, upon initial presentation, mandatory historical information includes changes in weight, stability of weight loss, desire for future pregnancy, history of abdominal surgery, and overall medical evaluation assessing for comorbidities such as diabetes, coronary disease, and the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Each patient needs to be carefully assessed, and based on the characteristics of each individual, the proper type of contouring procedure can be provided. 1

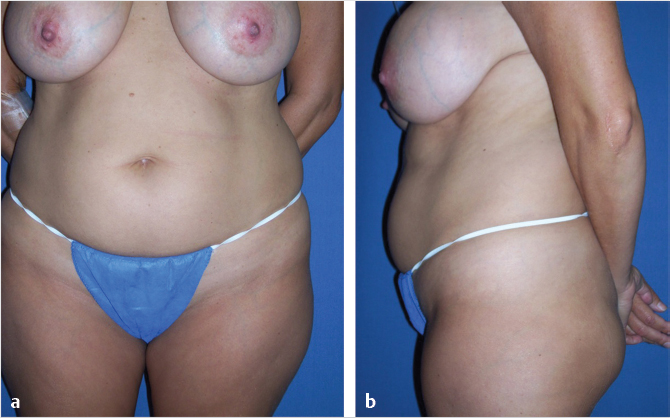

The physical assessment must evaluate the component irregularities of the abdominal wall: (1) degree and extent of adiposity, (2) quantity and location of loose or redundant skin, and (3) laxity of the musculofascial units. 2 Key in the examination is the determination of abdominal wall hernia or abdominal wall ports such as those used for gastric banding. Full examination of the patient’s abdomen is done in several positions: supine, sitting, standing, and the diving position. This provides a full appreciation of the degree of excessive soft tissue and the extent of musculofascial laxity. Careful palpation of the abdomen in the supine position allows assessment of rectus diastasis and the superior extent of the diastasis. It further permits detection of abdominal wall hernias. The quantity of excess tissue is confirmed with the patient supine while downward traction is asserted to the abdominal skin. This will permit fairly accurate assessment of the amount of skin to be removed and whether a full or mini-abdominoplasty would be appropriate. While standing, general visual inspection provides assessment of overall contours and areas of disproportionate fat distribution and skin excess or laxity. The sitting position will help delineate the extent of excessive or loose soft tissue. The diving, or waist-flexed, position allows the loose skin to fall away from the abdominal wall and provide further assessment.

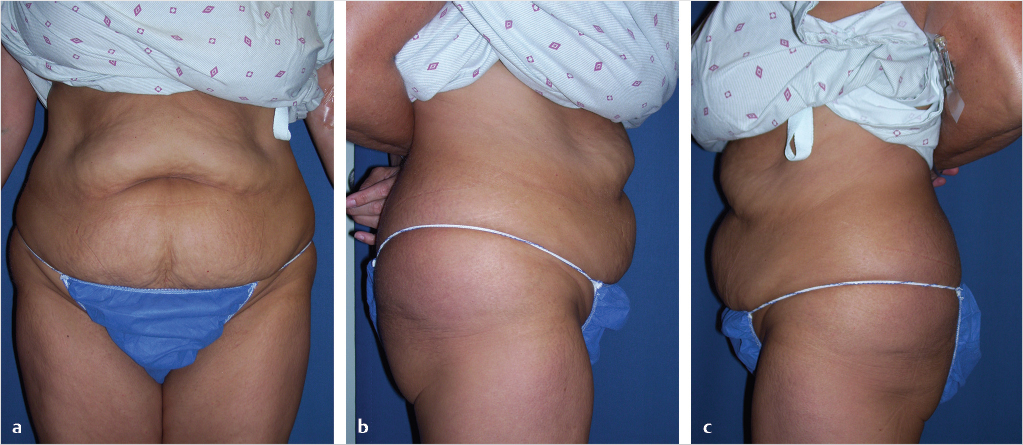

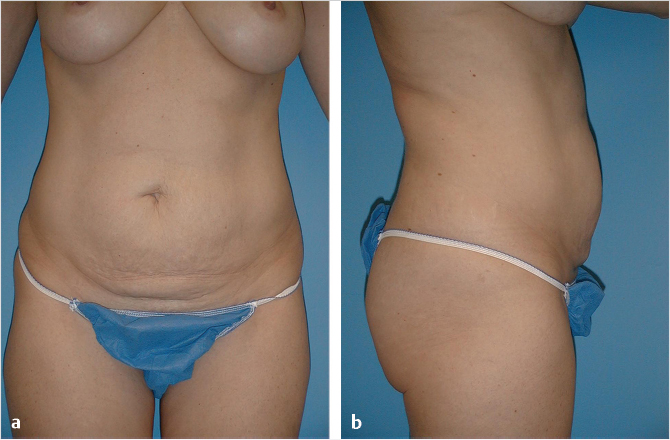

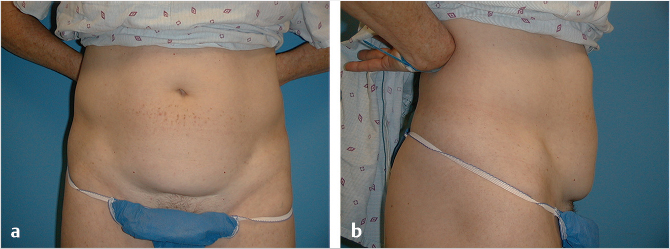

When the affected anatomic components affect the majority of the abdominal wall including the supraumbilical region, a full abdominoplasty with or without liposuction is usually indicated (Table 44‑1; Fig. 44‑1). For individuals with more limited or isolated deformities in the lower abdomen, effective treatment can be provided by mini-abdominoplasty, with or without liposuction of the abdominal wall or flank (Table 44‑2; Fig. 44‑2; Fig. 44‑3; Fig. 44‑4). 3 Mini-abdominoplasty can provide these patients with excellent correction of their abdominal deformities with significantly less morbidity and faster recovery than that which is associated with a full abdominoplasty. 4 , 5

Clinical feature | Description |

Body type | Overall fit and trim; not obese |

Abdominal contour | Lower, infraumbilical bulge |

Excess tissue | Confined to lower abdomen |

Lipodystrophy | Varies, but mild to moderate |

Musculofascial laxity | Lower abdomen only |

Rectus diastasis | No more than 2 cm above umbilicus |

Mini-abdominoplasty can also offer an understandable compromise for the patient who is not an ideal candidate for mini-abdominoplasty, but is unwilling to put forth the physical or financial outlay necessitated by the full abdominoplasty. 6 Patients with adiposity without skin laxity or significant muscle laxity can be treated with liposuction alone and no skin/soft tissue resection.

44.3 Preparation for Surgery

Diagnostic data in preparation for surgery would be similar for other elective major procedures and would be dependent on age, presence of comorbidities, and requirements of the surgical center in which the procedure will be performed. In general, the author requires a baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit on most patients. Massive weight loss patients also have nutritional parameters assessed via serum albumin level. Iron deficiency anemia is not uncommon in gastric bypass patients and requires correction prior to the surgery. Nongastric bypass patients with anemia require full workup for occult blood loss. Hypoproteinemia should be corrected via high protein diets and subsequent documented correction. Radiographs are not required unless the procedure is being done in combination with large hernia repair. In such a case, computed tomography would be used for assessment of the abdominal wall defect. Cardiac workup is dependent on patient age, history, and the facility in which the procedure is being done. In general, if an electrocardiogram is abnormal, internal medicine or cardiology clearance is mandatory.

44.4 Treatment

44.4.1 Treatment Options and Indications

The choices for surgical treatment fall broadly under two categories:

Complete or full abdominoplasty involving infraumbilical soft tissue resection, complete correction of musculofascial laxity, and umbilical translocation and inset. Most abdominoplasty patients fall into this category with laxity and excess of skin that then extends above the umbilicus and muscle laxity that is diffuse, combined with a long-length rectus diastasis. As a general guideline, ptosis of supraumbilical skin over the umbilicus is indicative of excessive laxity of the upper abdominal soft tissue that would not be fully corrected with a standard mini-abdominoplasty (Table 44‑1; Fig. 44‑1).

Mini-abdominoplasty in which tissue dissection and resection as well as rectus plication are significantly more limited to the inferior abdominal wall and the umbilicus is not translocated. Ideal candidates have loose skin confined to the infraumbilical abdomen. Diastasis of the rectus is limited to the infraumbilical region or only 1 or 2 cm superiorly. Overall muscular tone of the abdomen is good (Fig. 44‑2).

Liposuction can be added for contouring of the upper abdomen and flanks. When done cautiously, this can be combined with both full and mini-abdominoplasties with safe and reliable results (Table 44‑2; Fig. 44‑2; Fig. 44‑3; Fig. 44‑4). 7

44.4.2 Surgical Preparation

Historically, complete contouring via full abdominoplasties has been an inpatient procedure. However, outpatient surgery in properly selected patients has proven to be safe and effective. 8 , 9 Outpatient candidates should have limited or no comorbidities and as such are designated American Association of Anesthesiology Class I or II. Patients with systemic diseases, such as insulin-dependent diabetes, may categorize as Class III, and such patients are best treated in the hospital setting. Whether done as an inpatient or outpatient, effective control of postoperative nausea is needed. Preoperative medications such as ondansetron (Zofran) and aprepitant (Emend) have proven efficacy. Continuous mechanical intraoperative prevention via sequential compression boots is mandated in all abdominoplasty operations done under general anesthesia. Additionally, chemoprophylaxis for thromboembolic complications is advised. The American Association of Plastic Surgeons provides practice guidelines that encourage abdominoplasty patients to be treated with postoperative heparin. Preoperative heparin chemoprophylaxis continued postoperatively has also been proven safe and maximizes prophylaxis.

Most abdominoplasty procedures are done under general anesthesia. Choice of anesthesia is dependent on the individual patient, as well as the facility in which the surgery will be done. When combined with liposuction, breast surgery, or another procedure, the total length of the procedure must be considered, affecting the selection of anesthetic, but also mandating consideration of prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and the use of body warming devices. Mini-abdominoplasty can be performed under intravenous sedation combined with local anesthetic. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 In the latter technique, bilateral ilioinguinal nerve blocks are administered combined with direct infiltration of the incision line with local anesthetic. Tumescent liposuction solution consisting of 0.01% lidocaine with 1:000,000 epinephrine is also infiltrated into the lower abdominal wall in the region of flap elevation, in addition to the regions to be treated by liposuction. This augments the anesthetic effect and provides greater patient comfort. 14 , 15 The use of epidural anesthesia has been sporadically reported, but the potential complications as well as possible prolongation of predischarge recovery must be considered. If the operation to be performed is only a mini-abdominoplasty, then intravenous sedation combined with local anesthetic is easily applicable.

As with all body contouring procedures, the patient is marked preoperatively. Markings are started in the standing position. The proposed placement of the scar is confirmed with the patient such that it will be positioned within the panty line or swimsuit line. The transverse pubic incision is marked in the region of the superior aspect of the pubic hairline. This mark should be no higher than 6 to 8 cm above the superior aspect of the introitus in the midline. If a Pfannenstiel scar is present, the incision line should be inferior to it so that the associated subcutaneous fibrosis that tethers the skin to the fascia can be removed. For full abdominoplasty, the incision extends laterally along the inguinal crease past the anterior superior iliac spine to the position in which skin redundancy tapers away. The mini-abdominoplasty incision line is limited by the extent of tissue excess to be removed. The upper excision line for the full abdominoplasty begins centrally at the supraumbilical border and is carried laterally to meet the inferior line toward the flanks, judging the amount of skin to be removed by downward transection on the infraumbilical skin. For mini-abdominoplasty, the superior incision line is not drawn until the flap is raised intraoperatively. However, for purposes of planning, the skin to be excised usually encompasses about one-third to one-half of the vertical height of the skin between the pubis and the umbilicus. If liposuction is planned for the upper abdomen, flanks, iliac crests, or thighs, these areas are also marked while the patient is standing. At completion, all the markings should be demonstrated and explained to the patient with confirmation of proposed scar placement. However, it should be stressed to the patient that the final position of the scar cannot be guaranteed, rather best efforts are put forth to place the scar favorably.

44.5 Operative Technique

44.5.1 Full Abdominoplasty

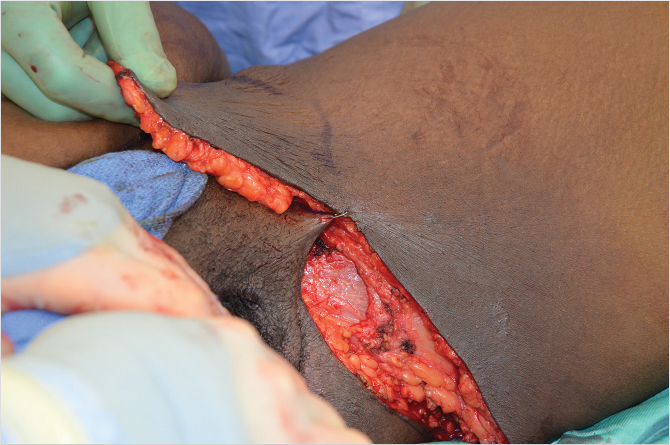

The components of abdominoplasty technique address multiple key anatomic features for restoration of abdominal shape and form. 16 The procedure is most often done in combination with upper abdominal and flank/iliac crest liposuction, as well as shaping of the muscular component of the abdominal wall. The procedure is most often commenced with liposuction. After appropriate institution of anesthetic support, cannula insertion incisions are made in the supraumbilical border and the lower abdomen, bilaterally within the tissue to be resected. Infiltration fluid for superwet liposuction need only contain epinephrine (1 mg epinephrine in 10,000 mL of crystalloid solution) if general anesthesia is used. While awaiting the hemostatic effect of the solution, the lower abdominal incision is created and carried through Scarpa’s fascia down to the loose areolar plane just superficial to the anterior rectus sheath and external oblique fascial aponeuroses. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are then elevated off the abdominal fascia superiorly and laterally to just below the level of the umbilicus. Liposuction is then done in the deep and superficial planes providing effective contouring. Suction of the upper lateral abdomen can be done aggressively as long as subsequent soft tissue dissection is done properly with perforator preservation (see below). This technique is frequently referred to as a lipoabdominoplasty. If an abdominal wall hernia is present, this must be repaired prior to the liposuction to avoid intestinal injury.

The umbilicus is circumferentially incised when the liposuction is complete. Dissection around the umbilical stalk is carried down to the muscle fascia. The abdominal skin/soft tissue flap is then dissected superior to the umbilicus, leaving the umbilicus attached to the abdominal wall. Dissection in the midline is then carried toward the xiphoid, ceasing when the entire diastasis is visualized or the skin laxity is mobilized. Dissection of the skin/soft tissue lateral to the midline is limited to the extent that permits plication of the rectus diastasis and proper tissue mobilization for contouring. When combined with liposuction, it is essential that the perforators from the rectus muscle are maximally preserved during this dissection so as to avoid inferior skin necrosis.

Dissection and retraction of the abdominal skin flap permits inspection of the musculofascial component of the abdominal wall and the anatomic cause of laxity that contributes to the convex external contour. The laxity is corrected by musculofascial plication, providing reconstruction of the correct anatomic relationships of the abdominal wall musculature. This should result in parallel alignment of the rectus muscles with a straight-line juxtaposition at the linea alba. The plication lines on the anterior rectus sheaths are marked to guide suture placement. The elliptical or crescent marks come together in the midline just above the suprapubic incision line and meet superiorly at the upper aspect of the diastasis (Fig. 44‑5; Fig. 44‑6). The author’s preferred method of plication is with inverted figure-of-eight braided nylon sutures. These permanent soft sutures require few knots, avoiding postoperative palpability, even in the thinnest patients. Alternatively, a running permanent monofilament suture can be used. Others have described methods of vertical and transverse plication that may be applicable when the extent of laxity is not fully corrected by a standard midline plication. 17 If the external obliques are laterally displaced in patients with exceptional muscular laxity, medial advancement of the oblique is done with running 2–0 polypropylene. This further shapes the abdomen and facilitates creation of a waistline contour (Fig. 44‑5; Fig. 44‑6).

At the completion of midline muscle plication, bilateral transverse abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are administered. This places local anesthetic into the plane deep to the internal oblique and anesthetizes the sensory innervation to the abdominal wall. This can be done under ultrasound guidance, limited open method with an oblique muscle-splitting technique, or a closed means. The author prefers the closed method in which a blunted needle is inserted just lateral to the linea semilunaris marking the junction of the external oblique to the rectus fascia. This is more readily accomplished prior to external oblique advancement, if needed. The needle is inserted with firm, but gentle pressure, and a double pop is appreciated as the needle passes through the fascia of the external and then internal oblique and the TAP is accessed. This is done along the entire length of the abdomen bilaterally with incremental injection of the local anesthetic. Long duration agents are used, such as bupivacaine or ropivacaine in appropriate dosing. 18 This can also be done before or after surgery by the anesthesiologist transcutaneously with ultrasound guidance.

Following plication, the excessive skin and subcutaneous tissue is retracted inferiorly with minimal tension to overlap the lower incision line. The midline point of overlap with the transpubic incision is marked and the flap is incised longitudinally in the midline. This point is secured temporarily to the lower incision line in the midline. This leaves two lateral “triangles” of excess tissue that can be appropriately marked and excised (Fig. 44‑7).

Aggressive skin excision that results in a very tight closure should be avoided since excessive tension will contribute to greater discomfort, wound dehiscence, and unfavorable scarring. Also, this will frequently cause gradual superior drift of the scar and subsequent elongation of the pubic hair domain superiorly. To avoid these results, skin excision is judged with the operating table only modestly flexed. It is occasionally necessary to leave a small vertical scar in the midline just at the junction of the lower transverse scar, corresponding to the original umbilical site.

Closed suction drains are often placed, but in select patients quilting sutures can be used to eliminate dead space with the added advantage of progressive tension reduction on the skin closure. 19 Prior to closure, the author favors the use of pain pumps that instill 0.25% bupivacaine without epinephrine for 2 to 3 days.

The position of the umbilicus is marked via direct palpation with the flap secured in position but prior to skin closure. As a confirmatory guideline, the proper umbilical position is in the midline at the level of the iliac crests. An inverted triangle of skin and underlying fat is then removed at this site. The author favors this over a circular excision since native umbilici are seldom perfectly circular, and circular insets tend to contract with time. The umbilicus is inset with an inferior midline absorbable monofilament that incorporates the abdominal fascia. This suture pulls the inferior inset closer to the abdominal wall and provides a downward slope of the umbilicus providing an aesthetically pleasing shape. The remaining inset is with absorbable monofilament suture and skin glue.

Tissue approximation is done in layers. Scarpa’s fascia, including the subcutaneous aponeurosis, is approximated with interrupted absorbable suture. The central, transpubic sutures also incorporate the abdominal fascia just above the pubis, acting to stabilize the position of the scar and prevent superior migration with time. The skin is closed with subdermal absorbable monofilament and skin adhesive. The soft tissues surrounding the suture line are infiltrated with bupivacaine without epinephrine to provide postoperative analgesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree