18 Periareolar Breast Augmentation

Summary

Periareolar augmentation is popular with some women as it may conceal an augmentation scar within the areola. The approach and its pros and cons are described in this chapter including some of the more recent concepts regarding capsular contracture risks associated with the procedure.

Key Teaching Points

The technique allows for concealment of the augmentation scar at the junction of the areola and the native breast skin.

The subpectoral or subfascial planes can be approached either through a subcutaneous lower pole dissection or through a transglandular approach.

Breast-feeding is unaffected by this procedure.

Nipple sensation may be slightly more affected than with other approaches.

Capsular contracture rates appear to be slightly higher with this approach due to contamination by bacteria from the nipple ducts during manipulation of the breast gland at augmentation.

18.1 Introduction

The periareolar approach has lost some of its earlier popularity due to concerns about increased capsular contracture related to bacterial contamination from the nipple. It does, however, remain a popular option in some quarters and several recent reports have presented successful outcomes.

In principle, the incision is placed from the 3 to 9 o’clock position along the lower half of the areola. It should be performed at the juncture of the areolar pigmentation with normal breast skin. If the incision is placed within the pigmented areola, there is a risk that the scar will heal with highly visible white discoloration, making it apparent to any observer that the patient has had breast surgery. The approach to the subpectoral space is carried out in one of two planes: directly through the breast parenchyma, or subcutaneously over the breast parenchyma to the inframammary fold.

Either of these routes requires some division of breast parenchyma, and most breast ducts contain bacteria, usually Staphylococcus epidermidis, theoretically increasing the risk of infection. There are no clear data to support this theoretical objection. What is of greater concern, however, is the potential for increased capsular contracture due to contamination of the implant during insertion with close proximity to the nipple. There is clear evidence that the nipple leaks bacteria during augmentation resulting in contamination of the periareolar area as the procedure progresses. The use of a Keller funnel helps to reduce this risk but may not eliminate it entirely due to bacteria being introduced during the dissection. As a consequence of these findings, I no longer use the periareolar approach for routine breast augmentation. If I perform a vertical mastopexy, I prefer to insert the implant through the base of the breast rather than risk dissecting into the parenchyma adjacent to the areola. I prefer an inframammary approach to avoid incisions through the breast parenchyma and the potential for infection. However, some women prefer this approach, and if it is to be used, the patient should be apprised of the risks. The lower periareolar incision generally heals with a minimally visible scar.

The periareolar approach is particularly helpful when the areola is of moderate-to-large diameter. I select this approach most commonly for a patient with tuberous breast deformity with herniation of breast tissue into the areola requiring periareolar mastopexy for correction. These patients typically have an element of constriction of the base of the breast with poor inframammary fold definition. Through a periareolar approach, the surgeon is able to release and widen the lower breast parenchyma with radial scoring, thereby widening the lower constricted breast and providing better contour when the tissue is redraped over the breast implant. This procedure is not recommended for women with very small areolar diameters.

Relative indications:

Patients with larger areolar diameters.

Tuberous breast deformity requiring concomitant periareolar mastopexy.

Standard breast augmentation in patients requesting concealed scars.

Relative contraindications:

Patients with very small areolar diameters.

18.2 Standard Subpectoral Periareolar Augmentation

Surgical Plan

Lower periareolar incision.

Subcutaneous dissection toward the inframammary fold.

Blunt division of breast parenchyma and the subpectoral pocket with direct release of inferior and medial pectoralis major fibers.

Development of symmetrical subpectoral pockets with lateral blunt dissection to preserve sensory pedicles.

Placement of round, smooth-surface implants.

18.2.1 Markings and Technique

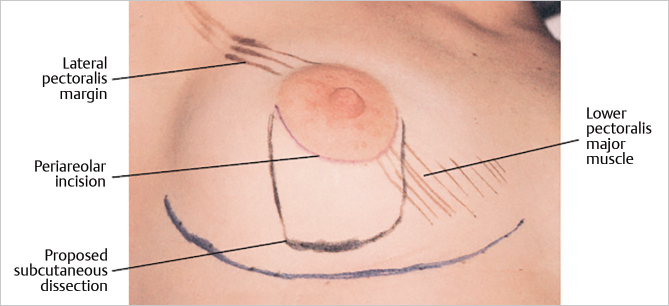

This patient has mammary hypoplasia with some involution. She has a relatively large areola (5.5-cm diameter). The periareolar incision will be made at the junction of the areola with the skin along the lower margin of the areola. It is usually 3.5- to 4-cm long. When the nipple–areola has some asymmetry or needs to be repositioned, the incision can be placed elsewhere along the outer circumference of the areola and can include a crescent excision of some of the areola or the adjacent skin. Placement within the areola is discouraged, because the scar may heal as a white line that is highly visible within the pigment of a darker areola.

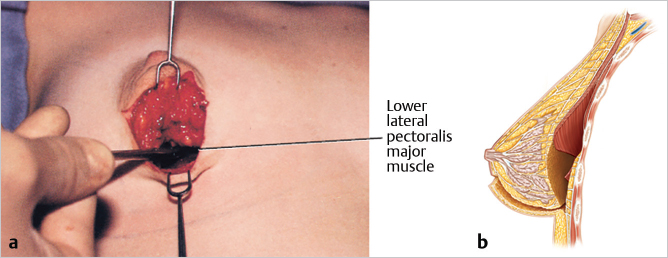

The markings also illustrate the lower lateral portion of the pectoralis major muscle and the limits of the submuscular dissection for the periareolar approach. A line is drawn around the lower half of the areola to mark the incision that will be made there. This approach gives adequate access for submuscular dissection. Although some breast tissue is invariably divided with this technique, the line of incision depicted below requires minimal parenchymal disturbance (▶Fig. 18.1).

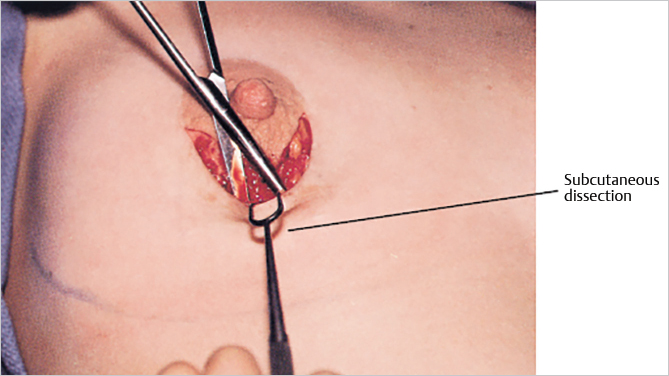

After the periareolar incision is made, superficial dissection at the level of the superficial layer of the superficial fascia is made down to the lower level of the breast (▶Fig. 18.2).

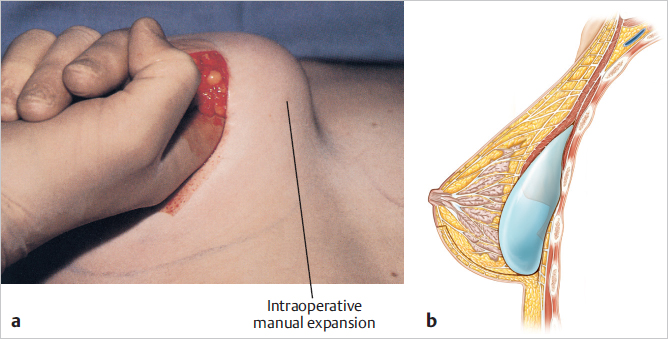

The width of the dissection must provide necessary access to make a deeper dissection. This means that it must admit two fingers. The incision is deepened around the lower pole of the breast and then upward on the deep fascia to the lower margin of the pectoralis major muscle. Lifting the breast upward “tents up” the pectoralis major muscle, and with blunt dissection the subpectoral space is entered and the pocket created. I also perform intraoperative expansion by lifting the breast and pectoralis major muscle away from the chest wall. The blunt dissection then sweeps laterally to develop the lateral pocket. When the intercostal neurovascular bundles are encountered, dissection goes around them to preserve breast sensation (▶Fig. 18.3).

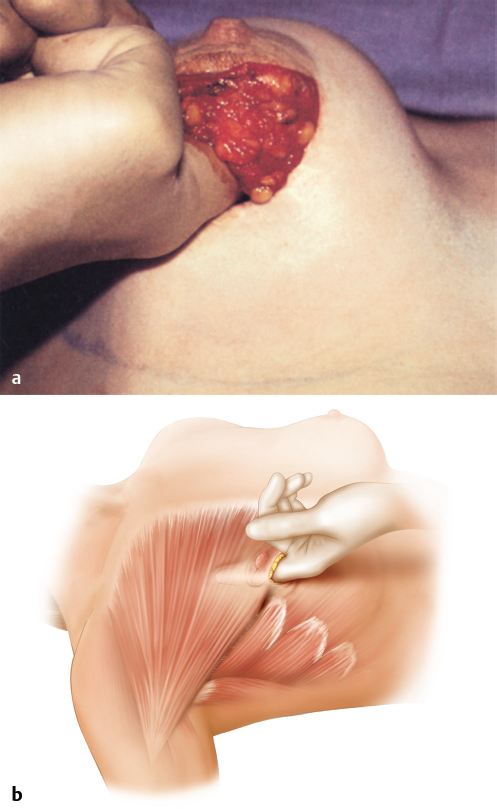

Dissection is then extended upward on the superficial layer of the deep fascia until the lower outer edge of the pectoralis major muscle is identified and its overlying deep fascia divided. The path of the dissection extends from the periareolar incision around the lower pole of the breast beneath the muscle (▶Fig. 18.4).

A pocket suitable for implant placement is created primarily by blunt dissection to the limits of the preoperative markings. This dissection is similar to that used for inframammary augmentation mammaplasty. It detaches the sternal origins of the pectoralis major muscle below the fourth intercostal space. The costal origins of the pectoralis major muscle are detached next. When this is not possible, I use a lighted retractor and the electrocautery unit to divide these fibers; however, the endoscope enhances illumination and visualization. It is essential to perform an adequate lower dissection and to have the dissection properly defined for the proposed inframammary crease.

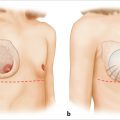

The pockets are checked for symmetry and hemostasis is secured. The lighted retractor is again helpful for visualizing specific areas that need to be released. Some bleeding from the breast parenchyma is more likely with the periareolar approach than it is with the inframammary approach. It is important to ensure that access to the pocket is sufficient for implant placement; additional extension of the skin incision or additional breast dissection may be necessary. Implants are placed in the subpectoral position and checked for symmetry (▶Fig. 18.5).

Before final closure, the breasts are checked for symmetry with the patient in the upright position. Again, only by placing the patient upright can the surgeon preview her appearance postoperatively and avoid asymmetry. The breast tissue is closed with running horizontal sutures, and the subcutaneous tissue and areolar skin layers are closed with intracuticular sutures (▶Fig. 18.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree