16 Subfascial Inframammary Breast Augmentation

Summary

This chapter describes the approach to subfascial breast augmentation, which has undergone a resurgence of interest in recent years. The procedure reduces functional and anatomical impact on the pectoral muscle preserving shoulder girdle function. It is less painful and less time-consuming than the sub-pectoral approach. It enables the surgeon to approach the midline of the chest more easily in an effort to create cleavage, which is difficult to achieve in a subpectoral augmentation with wide-spaced muscles.

Key Teaching Points

Less painful than a submuscular approach.

Provides much better cleavage formation.

Less functional impact than a submuscular augmentation.

Causes some attenuation of the overlying breast gland.

Less bloody dissection.

Less time-consuming dissection.

Eliminates the problem of animation deformity.

16.1 Introduction

For nearly 15 years after their introduction in the 1960s, implants were almost exclusively placed beneath the breast gland on top of the fascia of the pectoralis major muscle, in what became known as the subglandular approach. When there is adequate breast gland to drape over the implants, the patient can expect a fine result with this approach. However, the overall capsular contracture rate was shown to be higher for saline and silicone implants when they are placed in the subglandular position. The subglandular contracture rate appears to be influenced by the type of implant selected. Cohesive gel or form stable implants perform better in the subglandular position and may have a lower incidence of capsular contracture formation when textured surface devices are used. Because these implants are somewhat firmer and have a thicker shell, sufficient tissue cover must be present to minimize potential palpability and rippling of the implant.

Ruth Graf pioneered the concept of subfascial augmentation in 1998, publishing her data in 2003. Since that time numerous authors have promoted this approach noting that it provides for a more powerful lift to the breast gland in patients who are somewhat ptotic, and that the inclusion of the fascia seems to reduce the risk of capsular contracture to levels more closely approximating that of the subpectoral or dual-plane approach.

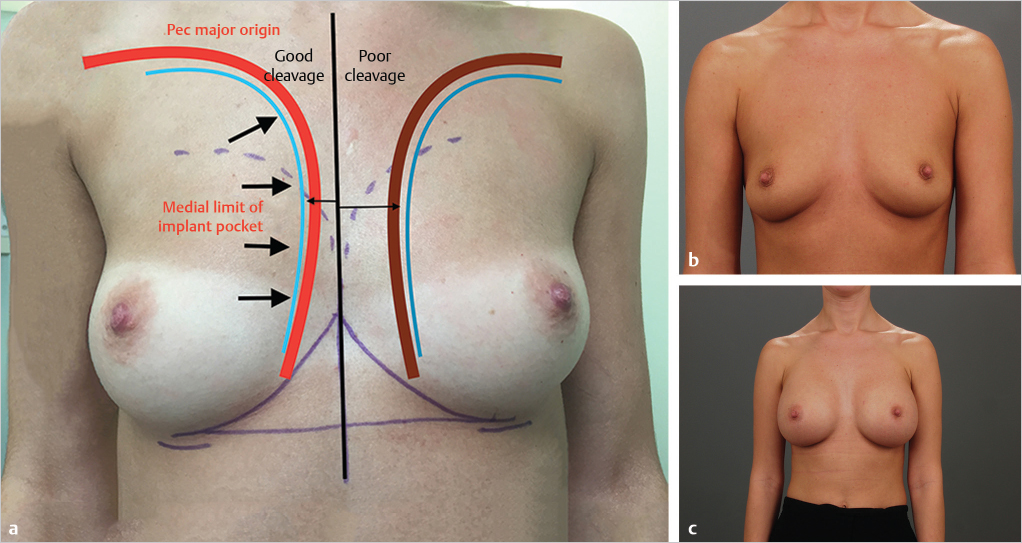

One of the most significant advantages of using the subfascial approach is the ability to control breast shape more directly. The medial origin of the pectoralis major muscle acts as a natural barrier to medial implant placement when the submuscular position is used. The wider the muscle origin separation on the chest wall, the more laterally displaced is the final implant position. Conversely, if the pectoral muscle origins are very close together on the sternal body, the more medial the position of a submuscular implant (▶Fig. 16.1a).

By placing the implants on the surface of the pectoral muscles, this mechanical limitation of medial implant placement by the muscle origin is entirely eliminated. Many small-breasted women presenting for breast augmentation have widely spaced pectoralis major origins as well as widely separated breasts. Submuscular augmentation in these patients creates the typical appearance of a wide valley between the breasts with a less than satisfying aesthetic outcome (▶Fig. 16.1b,c).

It has also been shown recently that submuscular implant placement results in thinning of the pectoralis major muscle by up to 50% with a loss of power of adduction approaching 15%. These physical limitations may be significant in a woman who participates in competitive sporting events or bodybuilding. Subfascial augmentation offers a better alternative in such patients.

Indications for the Subfascial Approach

Borderline breast ptosis.

Patients with widely spaced breasts desiring better cleavage.

Patients with very thick, well-developed pectoral muscles who exercise vigorously and do not wish to lose upper extremity power.

Patients who want to avoid animation deformity.

Patients with adequate breast volume to camouflage the implant.

Patients with poorly shaped breast such as triangulation.

16.2 Relative Contraindications

Very thin patients with minimal subcutaneous fat.

Patients with recurrent capsular contracture.

Patients with difficulty with mammographic evaluation of dense fibrous breasts.

Surgical Plan

Patient positioning with arms abducted.

Skin incision below the inframammary crease.

Dissection carried superiorly before penetrating Scarpa’s fashion at the original mammary crease.

Identification of the inferolateral border of pectoralis major and the overlying fascia.

Elevation of the breast gland and fascia of the pectoralis major muscle to create the subfascial pocket.

Pocket lavage with antibiotic solution.

Implant insertion with a Keller funnel.

A three-layer closure and dressing application.

16.3 Operative Technique

16.3.1 Preoperative Markings

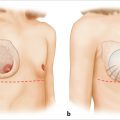

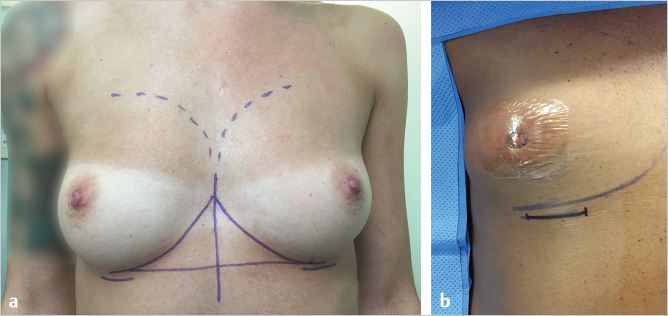

The patient is marked in the erect position with arms relaxed at her sides. The midline is marked and the medial extent of the dissection is carefully outlined so as not to run the risk of creating synmastia. The upper limit of pocket to section should be assessed and should not rise above the uppermost level of the anterior axillary fold. The inframammary crease is marked to ensure symmetric levels of the inframammary fold and the incision is placed either at or just below the inframammary crease as discussed earlier (▶Fig. 16.2a).

16.3.2 Operative Positioning

The patient is placed on the operating table in the supine with careful Paddington or pressure points. The arms are abducted on arm boards with soft padding to prevent nerve compression. The arms should not be abducted greater than 90 degrees. The nipple is covered with an occlusive dressing such as Tegaderm or Opsite (▶Fig. 16.2b).

16.3.3 Skin Incision

As described previously with the inframammary approach to subpectoral augmentation, I place the incision approximately 1 cm below the inframammary crease in order to allow it to rise up into the crease as skin is recruited onto the breast mound by the implant. It is important not to dissect down to the chest wall before heading toward the pectoral muscle, as this would create overdissection of the inferior aspect of the implant pocket below the true inframammary crease. If this is performed, it may predispose the patient to development of a double bubble appearance. Once the skin incision is made, the dissection is carried out in the subcutaneous plane above Scarpa’s fascia until the original breast crease is reached, at which point cautery dissection is carried down through Scarpa’s fascia to the inferolateral border of the pectoralis major muscle (▶Fig. 16.3).

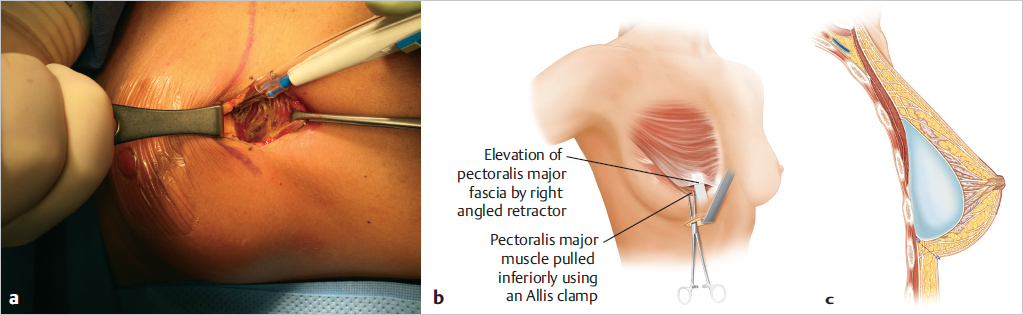

16.3.4 Identification and Elevation of the Fascia

The prepectoral fascia is easily identified on the surface of the pectoralis major muscle as it arises from the lower chest wall (▶Fig. 16.4).

The fascia is grasped with an Allis tissue clamp, and using cautery, it is elevated off the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle using direct illumination with fiberoptic retraction. Good-quality lighting greatly facilitates this procedure. The pocket is dissected over the surface of the muscle and is carried medially as far as necessary to create appropriate cleavage. Care should be taken not to breach the midline between the breasts, which runs the risk of creating synmastia.

Technical Pearl

Care should also be taken to preserve the intercostal perforators, particularly those arising in the second and third interspaces, as every effort should be made to preserve as much blood flow to the breast gland and overlying skin as possible. Laterally, it is important to attempt preservation of any lateral intercostal nerve branches supplying the nipple–areola complex with sensation.

16.3.5 Pocket Dissection

Once the subfascial plane has been clearly identified, dissection can be carried out with cautery using lighted fiberoptic retraction. The subfascial plane is not as easy to follow as is the submuscular plane and excellent retraction and lighting greatly enhance the surgeon’s ability to dissect the pocket accurately. Once the cautery dissection has been performed, gentle blunt dissection can be performed with an Emory or Agris-Dingman type dissector to delineate the boundaries of the pocket. This is an important step in that the shape of the pocket has to be very carefully sculpted by the surgeon in order to create the rounded contours necessary to achieve a pleasing aesthetic outcome. By comparison, a submuscular pocket is more forgiving and molds to the contour of the implant inserted due to the loose areolar tissue connections being stripped off the chest wall by the pressure of the implant in the submuscular space. By contrast, the borders and shape of the subfascial pocket will tend to constrain the implant and create more angular contours if not adequately dissected to the required shape (▶Fig. 16.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree