Viral Infections of the Skin

Jennifer K. Tan-Billet

Andrew A. Nelson

Viruses cause a myriad of skin conditions, ranging from benign nonspecific morbilliform eruptions to potentially life-threatening disseminated disease. With several hundred viruses in existence, it is not possible to comprehensively discuss all viral-mediated cutaneous eruptions in this chapter. Rather, this section will focus on the most common and important cutaneous manifestations of viral disease, with emphasis on presentation to primary care providers and initial management. The development of vaccines for diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella has greatly diminished the frequency of these previously common diseases; as a result, not all of these entities will be discussed. We hope that this chapter will serve as an overview and introduction to the cutaneous manifestations of viral infections.

|

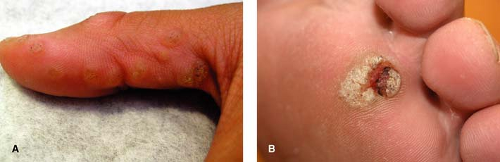

A 12-year-old boy is brought into the clinic by his mother. She complains of “warts” on his hands, which are embarrassing to him (Fig. 10-1A). They have tried numerous over-the-counter wart therapies, but none have worked. Several of his classmates have similar lesions. What is the most likely diagnosis? What is the best treatment option?

Verruca Vulgaris (Common Warts)

Background

Verruca vulgaris (VV) lesions represent infection by the human papilloma virus (HPV), a type of DNA virus. While the term verruca vulgaris is used to describe common warts, verruca plantaris refers to plantar warts and verruca plana refers specifically to flat warts. To date, more than 100 different HPV types have been identified; common warts are most associated with infections of HPV types 1, 2, and 4. While the majority of verruca vulgaris lesions are benign and self-resolve, they can be cosmetically unappealing and occasionally painful to patients. Treatment of these lesions is quite challenging for they are often refractory to repeated exposures to many therapeutic modalities.

Key Features

Verruca vulgaris is an extremely common condition, affecting nearly 20% of schoolchildren.

They are associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) infections, specifically HPV types 1, 2, and 4.

The majority of lesions self-resolve in 1 to 2 years.

Therapeutic options consist of either destructive or immunomodulatory therapies; treatment can be challenging, typically multiple treatments over several months are necessary.

Pathogenesis

Human papilloma viruses are a type of DNA virus. HPV can only complete its full life cycle when infecting squamous epithelial cells, particularly proliferating basal epithelial cells. Once the virus infects these proliferating basal epithelial cells, cell proliferation is upregulated. The epidermis then becomes thickened and hyperkeratotic through increased cellular division.

Figure 10-1 A Multiple verruca vulgaris on the thumb. B Verruca plantaris. Note the black dots (capillary thromboses). |

Clinical Presentation

Verruca vulgaris typically present as hyperkeratotic, rough, exophytic, round papules (Fig. 10-1A). These papules often have pinpoint black dots, which result from thrombosed capillary loops (Fig. 10-1B). The most common locations include the fingers, dorsum of the hands, and other sites exposed to trauma. Verruca vulgaris can be spread by autoinoculation; there may therefore be a linear arrangement of lesions as a result of this phenomenon. The majority of lesions are asymptomatic, although the lesions can be quite painful, particularly when located on the soles of the feet. HPV infects fully differentiated squamous epithelium, resulting in the massively thickened epidermis and stratum corneum that characterizes the cutaneous lesions. In some cases, VV can form a cutaneous horn which may be indistinguishable from an actinic keratosis, such as that shown in Figure 10-2.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes plantar clavi (corns), seborrheic keratoses, actinic keratoses, and squamous cell carcinoma. Rarely, a type of skin cancer called a verrucous carcinoma may be mistaken for a common wart; verrucous carcinoma tends to develop on the feet and is resistant to treatment (see Treatment section). When the lesion is adjacent to a nail, particular concern should be paid to possible amelanotic melanoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (see Chapter 25).

Diagnostic Methods

Most often the lesions can be diagnosed clinically. If the lesions do not respond to therapy, or there is any question regarding the diagnosis, a shave biopsy can be performed for confirmation.

Therapy

There is no current medication to “cure” HPV. Rather, current therapies focus on destroying the verrucous lesions or inducing an immune response against those cells infected with HPV. Because about 40% to 65% of warts resolve spontaneously in 2 years, providing no initial treatment is both reasonable and cost-effective. If warts are symptomatic, enlarging, spreading, or persistent, there are several treatment modalities to consider.

Destructive therapies (local anesthesia should be used for several of these therapies):

Salicylic acid peels: Available over-the-counter in products such as Mediplast, Compound W, Wart Off, Duofilm, or Dr. Scholls Clearaway. Of the current topical treatment modalities, there is sufficient evidence based on controlled trials available to support the use of this therapy. Patients should be instructed to apply 1 to 2 times daily and warned that effects are slow to achieve. This treatment is often used in combination with a pumice stone to pare down the lesion.

Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen): Often applied using an open-spray or cotton-tipped applicator for approximately 10 to 30 seconds to generate a 2 to 3 mm iceball around the wart (with cooling duration of approximately 20 to 60 seconds). Thin, filiform warts (Fig. 10-2) require freezing only of the lesion itself with little to no involvement of surrounding normal skin. For warts on the hand, a double freeze-thaw cycle likely confers little benefit over a single cycle and may result in increased discomfort and blister formation. For plantar warts, two freeze-thaw cycles appear to be more effective. Cryotherapy may be used in combination with paring of warts or salicylic acid application, though there is currently inconclusive evidence available to support the use of cryotherapy over salicylic acid as initial therapy for warts.

Cantharidin: This therapy, derived from the blister beetle, is painted on warts in a physician’s office. Application is painless but may cause subsequent blister formation in the next several hours. Cantharidin 0.7% is painted on to the wart and 1 mm of surrounding skin; the patient should not touch or remove the cantharidin initially. The cantharidin is then washed off 2 to 4 hours later.

Electrocautery: Care should be taken, as HPV has been reported to be aerosolized following electrocautery.

Laser therapy: Treatment with pulsed dye laser or ablative therapy with CO2 laser is typically employed. HPV can be aerosolized with this treatment.

Surgical excision: Though useful for stubborn lesions, surgical excision often results in increased scarring and the wart may recur following excision.

Immunomodulators:

Imiquimod: Stimulates toll-like receptors 7 and 8, increasing the production of inflammatory cytokines to kill the HPV-infected cells. Patients may apply 5% cream 3 to 5 times weekly for up to 16 weeks.

Cimetidine: An oral H2 blocker that has been reported to treat verruca through an unclear immunomodulatory effect. This may be a useful option for young patients that cannot tolerate destructive therapies. Doses of 25 to 40 mg/kg/day divided QID are typically prescribed, though results are generally varied and a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial demonstrated no benefit.

Interferon and bleomycin: Intralesional forms of these agents are sometimes used as second-line agents for recalcitrant warts. However, these injections can be painful for patients.

Alternative therapies:

Duct tape application: Apply to warts daily. Alternatively, patients may apply the duct tape and leave in place for up to 6 days. Duct tape requires up to 1 month or longer of treatment to be effective.

Hypnosis: Reported success in up to 25% to 50% of patients.

Hot water immersion: The affected area is soaked in hot water 2 to 3 times weekly for 30 to 45 minutes.

“At a Glance” Treatment

There are many suggested second-line therapies for warts that are summarized in the text.

First-line therapy includes:

Destructive therapies:

Salicylic acid peels: Available over-the-counter in products such as Mediplast, Compound W, Wart Off, Duofilm, or Dr. Scholls Clearaway. Patients should apply 1 to 2 times daily. If using with imiquimod, apply one in the morning and one at night. This treatment is often used in combination with a pumice stone to pare down the lesion. This may take months to achieve success.

Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen): Cryotherapy may be used in combination with paring of warts or salicylic acid application

Imiquimod: Apply 5% cream 3 to 5 times weekly for up to 16 weeks QD. Use in conjunction with monthly liquid nitrogen and salicylic acid.

Verrucous lesions that do not respond to the above therapeutic options should be evaluated by a dermatologist.

If the lesion does not respond to therapy, consider other conditions on the differential such as digital melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or benign clavus.

Course and Complications

Verruca vulgaris lesions can be quite refractory to therapy. The HPV infects keratinocytes at the base of the lesions. Thus, interventions are often unsuccessful, as they treat the lesions from the outside-in. Patients should be counseled that it will take many treatments spread over several months (usually one visit per 3 to 4 weeks) to treat these lesions and that there is no “cure” for warts. Additionally, patients should be instructed that warts can be passed from one person to another by direct physical contact and sometimes by sharing an object that has been touched by someone infected with HPV (such as gym mats and floors of showering facilities). Trauma, excess hand moisture, nail biting, and swimming pools can all increase the transmission of warts.

ICD9 Codes

| 078.10 | Viral warts, unspecified |

Condyloma Acuminata (Genital Warts)

Condyloma acuminata (Figs. 10-3A,B) are associated with infections by the human papilloma virus (HPV). In contrast to common warts, condyloma lesions are caused by infections with HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, and others. In the

1970s, the association between HPV infections and cervical cancer was first recognized. However, more recently, it has become apparent that certain specific “high-risk” HPV types are more closely associated with the development of cervical cancer. Condyloma acuminata are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

1970s, the association between HPV infections and cervical cancer was first recognized. However, more recently, it has become apparent that certain specific “high-risk” HPV types are more closely associated with the development of cervical cancer. Condyloma acuminata are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

Key Features

Condyloma acuminata is a common, highly prevalent sexually transmitted infection in young adults spread via intimate contact. It can be a manifestation of sexual abuse in young children.

Typically presents as soft exophytic growths in the groin and anogenital region.

Condyloma acuminata are caused by HPV infections. HPV types 16, 18, 31, and 33 are “high-risk,” and are associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. HPV types 6 and 11 are “low-risk” and are not associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer.

Treatment consists of topical destructive therapy or immunomodulatory therapies. Lesions can be quite refractory to therapy.

A vaccine has been developed that helps to protect against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in HPV naïve patients.

Human Herpes Viruses

|

A 18-year-old male with a longstanding history of severe atopic dermatitis presents to your clinic with a recurrence of a cold sore that he has had on and off for several years as well as a new rash. He says that he had a similar rash with the flare of his last cold sore, but this time it is much worse. He reports that he has ulcerations on his tongue and buccal mucosa as well as lesions on his arms, legs, and body, which “look kind of like targets.” He is feeling a bit more tired than normal and feels like he is “getting a cold” but he declines fevers or chills. The flare seemed to have started with a few painful “sores” around the mouth. He has cutaneous lesions as described above (Figs. 10-4A,B). What is the best diagnosis? What treatment is necessary at this time?

Background

Herpes simplex virus is a common, ubiquitous infection. In fact, nearly 90% of the world’s population between the ages of 20 and 40 are thought to have been exposed to HSV-1, as measured by positive antibodies. HSV-1 infections are most common on the lips and mouth; however, HSV-1 can also be the cause of genital herpes in approximately 10% to 20% of cases. HSV-1 infections can be primary, latent, and/or recurrent. The majority of affected patients are in the latent phase. Thus, while the majority of the population may have been previously exposed to HSV-1, a much smaller proportion has a clinical outbreak of HSV-1 at any given time.

Key Features

Common, ubiquitous infection with nearly 90% of patients between ages of 20 and 40; infection is with herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 (positive antibodies).

Most commonly appears as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on lips/mouth; however, can be a cause of genital herpes as well.

Clinically manifests as primary infections, latent infections, or recurrent infections.

Diagnosed via Tzanck prep, direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing, viral culture.

Treated with topical or oral antiviral agents such as acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir.

Pathogenesis

Transmission of HSV-1 can occur during symptomatic outbreaks or during asymptomatic latent periods. HSV-1 is most commonly spread through contaminated saliva or other secretions. The HSV-1 virus infects localized keratinocytes, and replicates locally. It can then spread up the nerve to the dorsal root ganglion, where it becomes latent. The virus can then be reactivated by multiple stimuli and result in recurrent infections.

Clinical Presentation

Primary HSV-1 infections typically develop a few days after exposure to the virus. These initial outbreaks are usually symptomatic, with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy developing 2 to 3 days before any cutaneous lesions. Primary HSV-1 infections commonly manifest as gingivostomatitis or pharyngitis with mononucleosis-like symptoms. The outbreak consists of multiple grouped “herpetiform” vesicles on an erythematous base (Fig. 10-4A). The lesions then crust and resolve over several weeks. In contrast to recurrent aphthous stomatitis (“canker sores”), HSV infections typically affect keratinized surfaces of the mouth such as the gingivae and hard palate; aphthous stomatitis tends to occur on the buccal mucosa and underside of the tongue.

Following the primary infection, HSV-1 infections can become latent. During this latent phase, the virus is localized to the dorsal root ganglion, where it is dormant. No clinical lesions or symptoms are present during this phase. The virus is then reactivated and spreads down the nerve to cause a clinical eruption. Reactivation can be caused by stress, sunlight, fever, sickness, or may occur spontaneously.

Recurrent outbreaks are often preceded by symptoms of burning and tingling in the lips, which may begin 1 to 2 days before the cutaneous outbreak. These symptoms are presumably related to the virus spreading down the nerve. Cutaneous lesions associated with recurrent HSV-1 are typically localized to the vermillion border of the lips and are characterized by small grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. The majority of these recurrent outbreaks are not associated with systemic symptoms, although lymphadenopathy and fatigue may occur. Recurrent outbreaks are typically milder and resolve quicker than primary infections, with the outbreak lasting approximately 1 week.

Recurrent flares of erythema multiforme (EM) are nearly always associated with flares of herpes simplex. As described in the case, patients’ EM will flare in conjunction with reactivation of HSV (Figs. 10-4A,B). Appropriate oral therapy for HSV will also suppress the EM flare.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Aphthous ulcers or “canker sores,” which are typically located on the buccal mucosa or undersurface of the tongue; erythema multiforme, a mucocutaneous condition which may be triggered by HSV; Stevens-Johnson syndrome, which usually has cutaneous target lesions in addition to oral lesions; pharyngitis associated with mononucleosis (EBV infections)

Diagnostic Methods

Historically, HSV infections were diagnosed by a Tzanck smear. This procedure involves unroofing a vesicle, scraping the base of the lesion, and applying cells to a microscope slide. Giemsa stain is then used to fix the specimen, followed by a brief rinse with water. A positive Tzanck is characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells, which represent infected keratinocytes. Although this technique allows for the rapid diagnosis of a human herpes virus (HHV) infection, it does not distinguish between HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV infections.

Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing utilizes antibodies specific to the different HHV types. This test is performed similarly to a Tzanck to obtain

basal keratinocytes and apply them to a microscope slide to be sent for DFA testing. Fluorescent antibodies to HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV are then applied to the slide; a rinse is then performed. If HSV or VZV infection is present, the specific antibody will bind to infected keratinocytes and will not be washed away with the rinse. The slides are then examined under a fluorescent microscope. If an HSV infection is present, the fluorescent antibodies will be seen. The DFA is a rapid test, but the true benefit is in the differentiation of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV.

Viral culture is performed by sampling the fluid beneath a vesicle. HSV-1 and -2 grow rapidly in culture, but a diagnosis still requires a few days. Viral culture can help differentiate HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV. However, it is important to note that VZV grows poorly in culture, and a negative culture does not necessarily exclude the diagnosis.

Antibody testing for HSV can also be performed. IgM antibodies can establish the diagnosis of a primary HSV infection. IgG antibodies only establish whether a patient has been previously exposed; they do not necessarily establish a diagnosis of recurrent HSV infection.

Treatment

Primary HSV infections are often severe and symptomatic and most patients are treated with antiviral therapy. A systematic review of acyclovir for treating primary herpetic gingivostomatitis found only weak evidence that acyclovir effectively reduces the number of oral lesions and prevents the development of new extraoral lesions. Patients with recurrent HSV may be treated with topical agents, such as 1% penciclovir or 5% acyclovir ointment, with limited expectations of useful effects. Oral therapy with acyclovir (dosed 5 times per day) or valacyclovir (dosed twice daily) is also an option for severe cases. Currently, no oral agents are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of primary oral HSV, though several dosing regimens have been reported in the literature. Mild, asymptomatic HSV-1 outbreaks require no therapy. However, topical agents and oral therapy can potentially abort or shorten an outbreak if given at the first sign of an infection, such as tingling in the lips. Therapy regimens are summarized in Table 10-1.

Finally, for patients with significant, frequent, recurrent outbreaks (including recurrent EM), suppressive therapy with either oral acyclovir or valacyclovir given on a low-dose daily basis is a therapeutic option. The dosing schedules for suppressive and episodic outbreaks are FDA-approved.

“At a Glance” Treatment

HSV type I therapy is summarized in Table 10-1.

Table 10-1 HSV Therapy | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Course and Complications

Primary HSV-1 infections can be quite painful and severe. They are self-limited infections, with symptoms resolving over 4 to 6 weeks. Unfortunately, the virus travels retrograde up the nerves and becomes latent, with the potential to reactivate.

Cases refractory to treatment should be referred.

For patients with recurrent erythema multiforme, consider suppressive antiviral therapy if they have more than several episodes per year.

Recurrent HSV-1 infections tend to be less severe and shorter than primary infections. However, they can be painful and occasionally associated with systemic symptoms such as lymphadenopathy. These outbreaks typically last 1 week, but can be potentially shortened or aborted with early antiviral therapy.

ICD9 Codes

| 054.9 | Herpes simplex without mention of complication |

| 695.10 | Erythema multiforme, unspecified |

| 695.11 | Erythema multiforme minor |

| 695.12 | Erythema multiforme major |

| 695.13 | Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| 695.14 | Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap syndrome |

| 695.15 | Toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| 695.19 | Other erythema multiforme |

Herpes Simplex Virus Type II

|

A 21-year-old college student presents to the student health service with an 8-day history of painful suprapubic, penile, and scrotal ulcerations (Fig. 10-5A). He noticed a few lesions on his lower pubis and decided to shave his pubic hair to get a better view. He is feeling poorly, reporting a fever, and has noticed some tender lymph nodes in his groin area. He recently had unprotected sexual intercourse and oral sex with his girlfriend, who came to his college for a short visit from her school in another state. He has done some Internet research and is confused because he thinks the skin lesions and his symptoms are consistent with “herpes” but does believe he could have gotten the infection as his girlfriend “only sleeps with me.” What is his diagnosis? What tests could be done to prove to him that this is a primary HSV infection?

Background

Genital herpes is most commonly caused by infection with the herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). While HSV-2 infections preferentially affect the genitalia, approximately 10% to 20% of genital herpes outbreaks are caused by HSV-1. In some cases HSV-2 may be the cause of oral herpes as HSV-2 infection is spread via sexual contact. As a result, HSV-2 infections before adolescence are rare.

Pathogenesis

HSV-2 infections are spread through close intimate contact. The virus then integrates into keratinocytes and spreads in a retrograde fashion to a dorsal root ganglion where it becomes eventually becomes latent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree