Fungal Infections

Fátima Akrouh

Sam Rodriguez

Peter C. Schalock

This chapter reviews the common cutaneous fungal infections likely to be encountered in a primary care setting. Superficial fungal infections primarily invade keratinized tissues, hair, and nails. These are some of the most common skin diseases worldwide and are particularly significant in immunocompromised hosts. Dermatophytes are fungi that digest and live on keratin. Common species include Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, and Microsporum species. Dermatophyte infection is common, with a 10% to 20% lifetime risk of developing a cutaneous fungal infection. Therefore, rapid and accurate diagnosis of such infections reduces morbidity and likelihood of spread. Dermatophytes possess enzymes that enable them to digest keratin, resulting in scaling, erythema, and injury of the involved structures. Tinea infection typically presents as “ringworm,” a lesion with central clearing and an elevated erythematous round border. Individuals with allergies and other immune deficiencies typically present with more pronounced and more numerous lesions. Bacterial superinfection and topical steroid use may also affect the presenting lesion and associated findings.

In diagnosing a fungal infection, it is important to note that many fungi are dimorphic and exist as both spores and hyphae. Spores are the reproducing form of yeast and are seldom observed on skin scrapings. The gold standard for diagnosis of fungal infection of the skin is the potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which often demonstrates hyphae, which are branching filamentous forms of fungi (Fig. 9-1).

Cutaneous fungal infections (Tinea) are generally classified by the area of the body they affect. Below, the different locations will be discussed. Tinea can present in multiple locations. When atypical or disseminated infection is observed, this should suggest the possibility of an underlying systemic deficiency or immune problem such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or diabetes mellitus.

General Treatment Principles

When selecting a treatment regimen for superficial fungal infections important factors to consider are efficacy, method of delivery, and cost. Topical treatment is first line for most superficial fungal infections but success rates vary highly on infection type, location, and patient compliance. Delivery methods include sprays, lotions, creams, powders, and gels (Table 9-1). Patients who do not respond to topical treatments or present with severe infections may be treated with oral antifungal agents.

While most skin dermatophyte infections are treated topically, tinea unguium (onychomycosis) and tinea capitis are primarily treated with oral agents. Oral antifungals have the ability to target areas where topical treatment is not practical or adequate such as the hair and nails, but carry the risk of greater systemic side effects such as hepatitis and gastrointestinal issues, potential drug interactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and cytochrome P450 inhibition. The most commonly used oral agents are terbinafine and itraconazole. Treatment regimens are summarized in their specific sections.

Consider obtaining a fungal culture for identification or confirming the presence of a dermatophyte from a nail clipping before starting any systemic medication. There are various methods for obtaining cultures or clippings, which are summarized in Table 9-2. Treating nails that are dystrophic from psoriasis or lichen planus with antifungal is ineffective, and exposes the patient to unnecessary risks from side effects.

Table 9-1 Topical Antifungals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 9-2 How to Collect a Fungal Specimen | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

A 2-year-old boy is brought to his primary care doctor by his mother for a flaky plaque with raised borders on his scalp (Fig. 9-2). She first noticed the round, 3-cm area on his left occiput 1 week ago while combing his hair. The hair over the plaque is slightly shorter than the rest of his hair. His mother wants to know if this is “just dandruff.” She also noted enlarged lymph nodes on the back of his neck.

Tinea Capitis

Background/Epidemiology

Tinea capitis (TC) is a common fungal infection, especially in young, school-aged children. The actual incidence is unknown, but the most commonly infected patient are African American boys under age 10 years. TC is by far the most common dermatophyte infection for children under 10 years of age (92.5%).

Pathogenesis

Tinea capitis is most commonly caused by dermatophytes from the Trichophyton and Microsporum genus. The infections are broken down into ectothrix and endothrix, defined by the location of the arthroconidia of the dermatophyte. Ectothrix infections have external arthroconidia and will fluoresce under Wood’s lamp exam with a green-yellow color. Endothrix infections have internal arthroconidia and do not fluoresce. The most common causes of each type of infection are listed in Table 9-3. In the United States, the most prevalent type is commonly referred to as the “black dot” form and is caused by Trichophyton tonsurans.

Key Features

Tinea capitis is the most frequent dermatophyte infection in children under 10 years of age.

Most commonly caused by dermatophytes from the Trichophyton and Microsporum genus.

Scaling and alopecia in a circumferential pattern on the scalp with a raised border.

Lymphadenopathy of the neck is common.

Oral antifungal therapy is treatment of choice.

Clinical Presentation

This infection typically causes scaling and alopecia in a circumferential pattern on the scalp with a raised border. The alopecia is often incomplete and

commonly affects the scalp, although it may also be found on eyelashes, eyebrows, facial hair, and pubic hair. Many patients are asymptomatic although some will complain of pruritus. In some cases the infection can cause marked alopecia, lichenification, or a severe inflammatory reaction known as a kerion (Fig. 9-2). Kerions are inflamed, granulomatous nodules that are often extremely painful and may be associated with sinus drainage, scarring, and alopecia. Complications of tinea capitis include secondary infection, often by Staphylococcus aureus, or kerion formation. Transmission may occur from person to person or via animals, soil, or fomites.

commonly affects the scalp, although it may also be found on eyelashes, eyebrows, facial hair, and pubic hair. Many patients are asymptomatic although some will complain of pruritus. In some cases the infection can cause marked alopecia, lichenification, or a severe inflammatory reaction known as a kerion (Fig. 9-2). Kerions are inflamed, granulomatous nodules that are often extremely painful and may be associated with sinus drainage, scarring, and alopecia. Complications of tinea capitis include secondary infection, often by Staphylococcus aureus, or kerion formation. Transmission may occur from person to person or via animals, soil, or fomites.

Table 9-3 Causes of Tinea Capitis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

Assessment should include careful examination of the scalp, face, and skin. Particular attention should be paid to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and facial hair. Wood’s lamp examination has been used to identify some tinea capitis types, though it has limited utility in North America as T. tonsuran does not fluoresce. Patients may also present with lymphadenopathy, particularly in the occipital nodes. Other diagnoses to consider when presented with a scaling plaque on the scalp are presented in Table 9-4.

Scrapings of the rash can be prepared using 10% KOH and examined on a glass slide. See Chapter 3 for a detailed description of this technique. When collecting specimens from children for culture or KOH, a toothbrush or moist gauze may be used to minimize irritation. Fungal cultures may also be obtained with either a blade or sterile swab and inoculated onto Sabouraud agar or Mycosel. Fungal colony growth requires approximately 6 weeks (Table 9-1).

Treatment

The first-line therapy for tinea capitis is systemic antifungal treatment. Topical therapies are not effective for the treatment of tinea capitis, as they do not penetrate the hair shaft, which may harbor organisms. The most common medication is griseofulvin dosing at 15 to 25 mg/kg daily micronized form and

10 mg/kg in the ultramicronized form for 6 to 8 weeks although treatment may take upward of 3 months. If treatment lasts less than 3 months in a healthy individual, blood counts and liver function tests (LFTs) are usually not indicated. The newer oral antifungal agents are equally effective in treating TC in most studies, but are significantly more expensive.

10 mg/kg in the ultramicronized form for 6 to 8 weeks although treatment may take upward of 3 months. If treatment lasts less than 3 months in a healthy individual, blood counts and liver function tests (LFTs) are usually not indicated. The newer oral antifungal agents are equally effective in treating TC in most studies, but are significantly more expensive.

Table 9-4 Differential Diagnosis for Tinea Capitis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients should be referred if tinea capitis persists despite 6 to 8 weeks of oral treatment, or if there is significant spread, suspected kerion formation, or secondary bacterial infection despite adequate oral treatment.

Some practitioners will concurrently start topical shampoos to reduce contagion, but they should not be used as monotherapy. Special attention should be paid to potential asymptomatic carriers. The infection may spread within those in close contact by fomite spread. Scalp cultures may be obtained to identify possible carriers who are often treated with selenium sulfide shampoo.

“At a Glance” Treatment

Systemic antifungal therapy is necessary for tinea capitis

Griseofulvin dosing at 15 to 25 mg/kg daily micronized form or 10 mg/kg in the ultramicronized form for 6 to 8 weeks

Also consider antifungal shampoo (ketoconazole 2% or selenium sulfide OTC)

Treat all cases of tinea capitis with oral therapy; topicals are not enough.

Consider treatment of all family members with an antifungal shampoo.

Course and Complications

Systemic treatment usually results in complete resolution, although treatment duration is often variable. The clinical course is highly individual as some patients may simply be asymptomatic carriers while others can have significant spread, inflammation, and permanent scarring alopecia.

ICD9 Codes

| 110.0 | Dermatophytosis of scalp and beard |

Tinea Corporis

|

A 16-year-old male athlete comes in with a 10-day history of a scaly, itchy rash on his trunk (Fig. 9-3). He thought it was dry skin, but it did not resolve with topical moisturizers. It has been enlarging in size. He is worried that it might be ringworm, as some other members of his wrestling team are also currently being treated.

Background/Epidemiology

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte fungal infection of the skin of the body, primarily the trunk. It begins as a round erythematous scaly patch or plaque, which spreads centrifugally with central clearing. Tinea corporis affects all age groups, though those most commonly affected are adolescents and women of child-bearing age. Children are more likely to have infections acquired from animals (zoonotic infection).

Pathogenesis

The infection can be caused by any dermatophyte but most pathogens are T. rubrum (47%), T. tonsurans, and Microsporum canis (13%). Transmission can occur from contact with human or animal carriers and from the soil. Autoinoculation may occur secondary to a prior or concurrent infection with tinea capitis or pedis. Risk factors include immunosuppression and exposure to skin-to-skin contact during athletics (e.g., wrestling, locker rooms).

Key Features

Tinea corporis presents as a scaling plaque on the trunk or extremities.

It spreads centrifugally with central clearing within 2 to 3 weeks of infection.

The most common pathogens are T. rubrum and T. tonsurans.

Treatment is primarily with topical antifungals, for extensive cases systemic therapy is necessary.

Usually has quick and complete resolution following appropriate treatment.

Clinical Presentation

Initial clinical presentation typically occurs between 1 and 3 weeks after exposure. The lesion is typically annular with raised borders although shape and

size may be highly variable. The lesion is usually scaly but vesicular, granulomatous, and verrucous variants have also been reported (Figs. 9-3, 9-4). The degree of inflammation will vary depending on causative organism and can be excessive in the clinical variant, tinea profunda, which results from an intense inflammatory response to the organism.

size may be highly variable. The lesion is usually scaly but vesicular, granulomatous, and verrucous variants have also been reported (Figs. 9-3, 9-4). The degree of inflammation will vary depending on causative organism and can be excessive in the clinical variant, tinea profunda, which results from an intense inflammatory response to the organism.

Prior treatment with corticosteroids can result in atypical presentations that may lack scaling and exacerbation of the infection when steroids are discontinued. This “tinea incognito” is important to consider in skin lesions that were presumed to be dermatitis but are not responding to therapy and often worsening. In many cases, the lesion(s) may have subtle scale and are copiously KOH positive on exam.

Diagnosis

Clinical exam of the affected site(s) with KOH exam of all scaling plaques as described in Chapter 3 is necessary for any lesions thought to be tinea corporis. Fungal culture may be useful in cases recalcitrant to topical therapy. Rarely is a skin biopsy indicated.

It is important to distinguish tinea corporis from psoriasis. As shown in Figure 9-4, the distribution may be similar to psoriatic plaques. A KOH exam in this situation would easily differentiate between psoriasis and a dermatophyte infection.

Treatment

Treatment with a topical antifungal is usually sufficient. A typical starting regimen for an adult would include topical ketoconazole, econazole, or terbinafine applied once daily to the affected area. Treatment duration varies based on severity of infection and typically requires 2 to 3 weeks of therapy. Patients who fail to respond to topical treatment may be candidates for oral therapy agents such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, and ketoconazole.

Corticosteroids should, in most cases, be avoided as they may suppress physical signs and worsen the infection. Rarely, cases of inflammatory tinea will respond to both antifungal and corticosteroid therapy. A moderate-potency steroid such as triamcinolone acetonide and a separate antifungal such as

econazole nitrate cream is recommended. For inflammatory, pruritic cases, if an anti-inflammatory is necessary, treat with triamcinolone twice daily for 1 week and continue the antifungal for a total of 3 weeks.

econazole nitrate cream is recommended. For inflammatory, pruritic cases, if an anti-inflammatory is necessary, treat with triamcinolone twice daily for 1 week and continue the antifungal for a total of 3 weeks.

Patients with recurrent or recalcitrant infections despite multiple topical and/or oral treatments as well as preventative measures should be referred for further workup. Special consideration should be given to patients who are immunocompromised, as they may have atypical presentations and may be subject to more complications.

Differentiate between psoriasis and tinea corporis in extensive cases.

Avoid usage of topical corticosteroids if possible.

“At a Glance” Treatment

First-line therapy: topicals such as clotrimazole, miconazole, ketoconazole, econazole, or terbinafine applied once daily to the affected area

Patients who fail to respond to topical treatment may be candidates for oral therapy. Terbinafine 250 mg PO QD × 2 weeks often is successful

Alternate oral therapy: itraconazole, fluconazole, ketoconazole, or griseofulvin

Avoid topical corticosteroids other than in cases of inflammatory tinea

Tinea Cruris

|

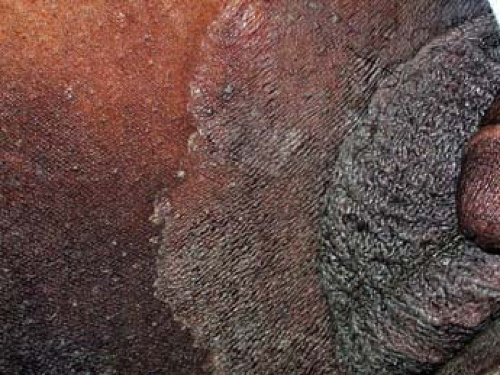

A 67–year-old man with a history of well-controlled type II diabetes comes to your office complaining of 2 weeks of itching “down there” (Fig. 9-5). He says that he noticed a raised, reddish patch on his upper inner thigh extending into the inguinal fold. He has been using baby powder and a “medicated powder” for the itching, but they have not provided relief. The itching is driving him crazy and he wants to know what treatment options are available.

Background/Epidemiology

Tinea cruris is a common dermatophyte infection of the inguinal folds, but may extend to the inner thighs, buttocks, and abdomen. It is rarely seen in children and is three times more likely to be seen in males.

Pathogenesis

Tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection most often caused by E. floccosum, T. rubrum, and T. mentagrophytes. Risk factors include obesity, abrasive garments, and excessive perspiration.

Key Features

Tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection of the inguinal folds and inner thighs/buttocks/abdomen.

The scrotum/vulva are nearly always spared.

Treatment is with topical antifungals. Recalcitrant cases may require oral therapy.

Clinical Presentation

Tinea cruris typically presents as an erythematous, pruritic plaque in the inguinal folds, inner thigh, or between the scrotum/labia majora and inner thigh. Like other dermatophyte infections, the lesion often has a raised border that can have vesicles or pustules in active edges. The scrotum is often spared and scrotal involvement should prompt suspicion of a candidal infection. Several examples of tinea cruris are shown in Figures 9-5 and 9-6. Secondary lesions may result from bacterial superinfections. Chronic cases may progress to include lichen simplex chronicus or prurigo nodules.

Diagnosis

A KOH exam is important for confirming the diagnosis of a dermatophyte infection. The areas of highest yield to scrape organisms from are active border

regions. Equivocal specimens should be sent for culture. Assessment should include careful examination of the scalp, face, skin, fingernails, and groin. Diagnoses also to be considered include: candidiasis, cellulitis, intertrigo, psoriasis, or contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant) (Table 9-5).

regions. Equivocal specimens should be sent for culture. Assessment should include careful examination of the scalp, face, skin, fingernails, and groin. Diagnoses also to be considered include: candidiasis, cellulitis, intertrigo, psoriasis, or contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant) (Table 9-5).

Treatment

Similar to tinea corporis, first-line treatment for tinea cruris infections consists of topical antifungals. Patients who are refractory to topical treatment may be candidates for systemic antifungal therapy. As this condition may recur in many patients, prevention is an important part of treatment. Patients should be instructed to wear loose-fitting clothing, wash contaminated clothing, dry completely after bathing, and lose weight. Use of topical drying powders is often helpful. Additionally, patients should be advised to avoid touching the groin area after contact with the feet because tinea cruris is often caused by hyphae carried from fungal-infected feet and/or nails.

“At a Glance” Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree