Key points

- •

Vertical mammaplasty causes fewer scars, narrows the wide breast, reduces the bottoming out phenomenon, improves projection, and offers better long-term shape when compared with the inverted T techniques.

- •

It can be performed in patients with several degrees of breast hypertrophy and ptosis, but the best results have been achieved in mild and moderate cases. Parenchyma resection follows the vertical principle, which narrows the base, increasing breast projection and avoiding the flat and broad shape. Periareolar skin compensation reduces the length of the vertical scar, avoiding its elongation across the inframammary crease.

- •

In order to obtain a better long-term outcome, it is mandatory to redefine breast shape with internal tissue, not with skin sutures, therefore avoiding exaggerated scar tension.

- •

Better and long-term breast shape can be achieved using the chest wall based flap under a sling of major pectoralis muscle, together with liposuction to the lateral breast area.

Introduction

Breast reduction and mastopexy remains one of the most challenging operations in plastic surgery. Since the surgeon is usually faced with hypertrophic and/or ptotic breast tissue that requires a well-planned and careful approach, many believe that perfection is hard to achieve. The fact that many different options exist does not necessarily make this problem any easier. The goal of mammaplasty /mastopexy is to provide long-lasting results, reducing the breast size, improving upper pole fullness, repositioning the nipple–areola complex and tightening the skin brassiere.

Currently, aesthetic breast surgery not only reduces breast size, but also restores a firm and youthful look to the breast. This is not possible without placing incisions on the breast. However, in some cases, hypertrophic scarring may also jeopardize the final appearance. Thus, minimizing the extent of scarring remains a key point when modifying existing techniques and introducing innovative procedures. The so-called ‘short scar or limited scar mammaplasty’ has evolved out of the necessity to reduce the length of the incisions, as patients are highly concerned with the aesthetic outcome and often request the shortest scar possible. Trading a ptotic breast for a visibly scarred breast with a chance of recurrent ptosis is a poor choice. The term ‘short scar mammaplasty’ is not limited to one specific technique but is used to describe techniques that minimize the extent of scarring. There are basically four different scarring patterns, with some variations to each one (periareolar, vertical, L-shape and inverted T short scars). Usually, a number of different techniques exist for each pattern ( ).

Vertical mammaplasty is an appealing technique because it promises fewer scars, narrowing of the wide breast, reducing the bottoming out phenomenon, improved projection, and stable long-term shape when compared with the inverted-T techniques ( ). Several authors have reported vertical techniques that are conceptually similar but vary in some details. Issues that differ among previous descriptions include the role of liposuction (integral or incidental), pedicle design (superior or medial), and whether or not to undermine the lower pole skin, imbricate the lower pole, or elevate the parenchyma by suture to the pectoralis major muscle ( , , , ). Vertical mammaplasty is quite different from inverted T techniques in both design, execution, immediate and long-term results ( , , , , , , , , , , , ). It is inherently more intuitive and requires a certain amount of experience before a surgeon becomes proficient. Parenchyma resection follows the vertical principle, which narrows the base, increasing breast projection and avoiding the flat and broad shape. Immediate postoperative result quite frequently is not optimal due to pleating of the skin in order to avoid extending the scar, which is presumed to ‘settle out’ favorably over time. The vertical component of the scar is longer than in inverted T techniques, because less pronounced parenchyma descent is expected, causing minimal elongation of the vertical scar.

Dartigues was the first author to describe a vertical scar technique used for mastopexy ( ). In 1957, Arie described a technique for reduction mammaplasty finishing with a vertical scar which did not gain popularity because the vertical scar often crossed the inframammary crease and extended onto the chest wall, leaving an unsightly scar ( ). It was only in 1969 that Lassus renewed interest in vertical scar breast reduction by developing a technique using a superior dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple–areola complex; a central excision en bloc of skin, fat, and gland; no undermining and finishing with a vertical scar ( ). In 1994, Lejour described a modification of Lassus’s technique, beginning the breast reduction with liposuction to eliminate fat contributing to breast volume ( ). The skin surrounding the excised area was undermined and the superior dermoglandular pedicle was sutured to the pectoralis fascia, joint pillars to improve breast shape, and suturing the skin of the vertical wound above the inframammary crease.

Lassus’s and Lejour’s techniques demonstrated positive outcomes when applied not only in mild and moderate cases of breast hypertrophy, but in severe cases as well. Hammond adds the vertical component intraoperatively in his short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction mammaplasty/mastopexy, initially using a periareolar incision and then working redundant skin to the lower portion of the areola where it can be excised in a vertical fashion ( ). Graf & Biggs (2002) described an interesting concept to increase longevity and especially enhance upper-pole fullness of the breast. They use a chest wall based flap passed under and held by a pectoralis muscle sling ( ).

Recently, working with the philosophy of the periareolar technique associated with the vertical scar technique, it has been possible to reduce scar length, thus avoiding its elongation across the inframammary crease by compensating for skin excess around the areola. It was observed that in every single technique performed, the breast shape after descent resulted in loss of upper pole fullness. Some authors used the inferior portion of breast tissue to fill in the upper pole or the areola to achieve a better breast shape. In addition to scar evolution, since 1994 we have been using a sling of major pectoralis muscle to allow long-term maintenance of upper pole volume ( , ). In order to obtain a better long-term outcome, it is mandatory to redefine breast shape with internal tissue, not with skin sutures, therefore avoiding exaggerated scar tension. It has been observed that passing the chest wall based flap under a sling of pectoralis major muscle permits a longer definition of the breast shape and upper pole fullness. Liposuction on the lateral breast area helps to better define the lateral fold.

Therefore, Ribeiro’s technique was then utilized, which is an inferior pedicle flap ( ), modified by Daniel, who associated a bipedicled flap of major pectoralis muscle to keep Ribeiro’s flap in a higher position ( ). The approach was switched from inferior pedicle flaps to flaps based only on the thoracic wall vasculature, completely detached from the surrounding structures, keeping the overlying dermis to give better support and shape to the flap, fixating it to pectoralis fascia. The association of vertical mammaplasty principles with chest wall based flap held by a bipedicle pectoralis muscle flap has improved long-term results.

The upper pole of the breast remains with a good volume and the vertical scar is placed above or at the level of the new inframammary crease with a minimal breast descent. This technique is indicated either in patients who need only a mastopexy and reduction, no breast tissue or for breast reductions where excessive breast tissue is resected from the columns or base of the breast, after the thoracic wall flap is built and fixed. With this technique we realized that less breast tissue is resected compared with the other techniques without the thoracic flap. In large hypertrophies or severe ptosis, the ‘D’ point should be marked higher to the ‘M’ point, by up to 4 cm. This maneuver is done to leave skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lower breast pole as part of the thoracic wall, with a higher new inframammary crease, decreasing skin compensation in the vertical scar.

The redundant skin in the vertical can be compensated with a subcuticular suture that shortens this scar. During the first 2 months of the post-operative period there is flattening of the wrinkles with no need to remove skin horizontally in the inferior portion of this scar, as suggested by Marchac ( ). A periareolar round block suture is done with the purpose of reducing even more the length of vertical scar by compensating skin excess around the areola. Taking larger suture bites in the outer skin circle in order to compensate the skin around the areolar.

The goals of a vertical scar technique associated with chest wall based flap and bipedicled major pectoralis muscle flap are: maintain the breast upper pole fullness with the patient in a standing position, providing a better aesthetic outcome in the long-term follow-up; avoid vertical scar crossing the new inframammary crease; project the nipple–areolar complex even using the periareolar round block suture.

Personal technique

Preoperative preparation

Usually every patient is being followed annually by a mastologist. If not, the patient is referred for a specialized breast evaluation prior to the operation. Pre-operative mammograms and, when necessary, a breast ultrasound is routinely ordered. Smokers are requested to stop smoking at least 1 month before and for 2 weeks after surgery. On the day before the operation, skin is marked and an antiseptic soap is prescribed.

Markings

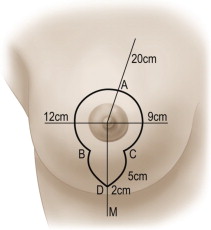

The same skin markings can be used to perform either breast reduction or mastopexy, with the only difference being during surgery where tissue removal is performed where indicated. A line from the sternal notch to the xiphoid process is drawn (midline). The meridian line is drawn from the midclavicle to the NAC, crossing the inframammary crease (‘M’ point), which is 12 cm or more from the midline. The ‘A’ point is marked 18–20 cm from the clavicle or 20–22 cm from the sternal notch. With a horizontal maneuver, the breast is moved medially and laterally and two points (‘B’ and ‘C’) are marked, using the vertical line inferior to the areola as a reference, which demonstrates the skin in excess. Using these three points as a reference, a curved line is drawn around the areola in an oval shape, similar to the periareolar technique. The medial portion of this line is, on average, 9 cm from the midline, and the lateral portion is, on average, 12 cm from the anterior axillary line. Point ‘D’ is marked, 2–4 cm above point ‘M’. Points ‘BD’ and ‘CD’ are joined together in a curved line of approximately 5–7 cm ( Figures 15.1,15.2 ).

Surgical technique

Surgery begins with de-epithelialization of the area previously described keeping the subdermal plexus intact. Dermis is incised along the marked lines, up to 1.5–2 cm superior to points ‘B’ and ‘C’ sparing the upper portion of the areola, which is the pedicle for the NAC ( Figure 15.3 ). Dermis is also incised horizontally 1 cm inferior to the areola and subcutaneous tissue is incised perpendicular to the plane of the thoracic wall, reaching the pectoral fascia at the level of the fourth intercostal space.