Chapter 7 Tendon Tissue Engineering and Bioactive Suture Repair

Outline

When graft material is required, repairs are currently limited to autografts such as the palmaris longus, plantaris, and toe extensor tendons. Limitations of autograft harvesting include donor site morbidity and additional anesthesia and operative time. In cases of mutilating injuries to the hand (Figure 7-1), the demand for graft material may outstrip the autograft supply in a patient, leaving these patients without a good solution for restoring hand function.

Tissue Engineering

One of the earliest articles broadly defining tissue engineering was a 1993 Science article by Langer and Vacanti.1 In this article, they defined the nascent field of tissue engineering as “an interdisciplinary field that applies the principles of engineering and the life sciences toward the development of biological substitutes that restore, maintain, or improve tissue function.” They described three general strategies of tissue engineering: (1) cells or cell substitutes, (2) tissue-inducing substances such as growth factors and delivery vehicles, and (3) cell-seeded scaffolds. These principles have been applied to clinical needs in hand surgery, resulting in commercially available products including engineered skin substitutes2 and allogeneic nerve grafts.3 However, a tissue-engineered tendon is not yet available.

Tendon Biology

Structure and Anatomy

Collagen is the basic structural unit of tendons.4,5 It is organized into a hierarchical structure of progressively larger and more organized subunits to form the crimped or sinusoidal pattern visible by light microscopy.

While collagen is the major constituent of tendons, proteoglycans are critical to the biological and mechanical functioning of tendons.6 Proteoglycans promote hydration through hydrophilic subunits and mediate interactions between structural units of the tendon, which are important determinants of the viscoelastic properties of tendons. Another important function of proteoglycans is their role in promoting cell signaling to mediate growth, proliferation, and migration.

Brockis and others made early observations about the vascular supply to flexor tendons.7 They observed that tendons receive their blood supply through the musculotendinous junction, the paratenon surrounding the tendon in the extrasynovial region, the vincula within the intrasynovial region, and the osteotendinous insertion. In addition to vascular nutrition, the intrasynovial portion of the tendon receives nutrition by diffusion through the synovial fluid.8,9

Tendon Healing

Tendons heal slowly because of their hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and low metabolic rates.10 This prolonged healing process requires immobilization to reduce the risk of tendon rupture or gap formation. The duration of this immobilization must be balanced against the risk of adhesion formation. Modulating this healing process to create a strong tendon repair with minimal adhesion formation requires an understanding of the three stages of tendon healing: inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling.4,10

Extrinsic Versus Intrinsic Healing

It was originally thought that tendons must heal by an extrinsic process in which ingrowth of new cells occurred through vascularized adhesions to surrounding tissue.11 It was later demonstrated that intrasynovial tendons could heal by a process mediated by cells intrinsic to the tendon.12,13 This suggested that adhesion formation might not be necessary for tendon healing if cells within the damaged tendon are available to mediate repair.

Tendon Tissue Engineering

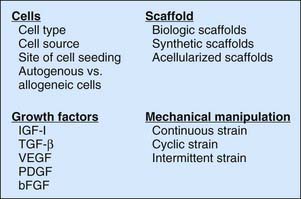

Tissue engineering a tendon requires an understanding of the basic science of tendon healing and tendon function. This knowledge can then be applied to designing and choosing the components of a tissue-engineered tendon, which can include cells, a scaffold, growth factors, and mechanical manipulation (Figure 7-2), some or all of which can be used to create the final tissue-engineered product.

Cells

Cell Type and Cell Source

Tenocytes are the predominant cell type of native tendon. Thus, they should be capable of restoring function of a tissue-engineered tendon construct. In a study using unwoven polyglycolic acid scaffolds seeded with hen tenocytes, Cao and colleagues demonstrated that tenocyte-seeded scaffolds resembled native tendons in histologic structure, collagen arrangement, and breaking strength.14 However, tenocytes may not be a practical source of cells because autologous tendon harvest required for their isolation results in donor site morbidity. They also expand very slowly in culture, which may make them further impractical due to a lengthy in vitro expansion time following cell isolation and before seeding of the tendon construct.

Human dermal fibroblasts are another terminally differentiated cell type that closely resembles tenocytes and have been widely considered as a candidate cell line for tendon tissue engineering. Like tenocytes, dermal fibroblasts are derived from the mesoderm, have similar morphology, and have similar extracellular matrix production capacity. Harvest of autologous dermal fibroblasts through a simple skin biopsy would cause minimal morbidity or expense, which is a notable advantage over tenocytes, and they are easily and rapidly expanded in culture. In a study comparing human tenocytes and human dermal fibroblasts, each cell type was isolated and grown separately on a polyglycolic acid scaffold.15 The authors found no difference in a number of outcome measurements comparing tenocyte-seeded and dermal fibroblast–seeded tendon constructs, including gross structure, histology, collagen deposition, collagen fibril diameter, and construct strength. These results suggest that dermal fibroblasts may be a suitable substitute for tenocytes, which will also avoid the problems with using autologous tenocytes.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a multipotent cell line present in adult bone marrow and adipose tissue that may be cultured as undifferentiated cells or driven to differentiate into mesenchymal lineages including tenocytes, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes.16 Although harvest of MSCs from bone marrow is invasive, provides low yields, and requires time consuming and expensive in vitro expansion in culture, it does not carry the donor site morbidity of tenocyte harvest. Several groups have demonstrated improved tendon strength, remodeling, and tissue formation when seeded with bone marrow–derived MSCs.17–19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree