Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc, scleroderma) is an uncommon autoimmune connective tissue disease of unknown etiology. The clinical hallmark of the disease is cutaneous sclerosis. Ninety-five percent of SSc patients present with cutaneous sclerosis early in their course and therefore it is important for dermatologists to be able to recognize these skin changes. The cutaneous sclerosis of SSc is unique in that it is symmetric, affects the hands at a minimum, and may generalize. It is also accompanied by Raynaud phenomenon. The pathogenesis is not well understood, but involves interactions with the vasculature, the immune system (with characteristic autoantibodies), and the extracellular matrix. Internal organ involvement is commonly observed. Pulmonary involvement is the most common cause of death, and screening for lung disease is important. Treatment is focused primarily on managing associated internal organ involvement. Therapeutic options for the cutaneous sclerosis remain limited. The differential diagnosis of cutaneous sclerosis is reviewed in this chapter.

Keywords

autoimmune connective tissue disease, autoimmune disorder, systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, sclerosing disorders, diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon, calcinosis cutis, eosinophilic fasciitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, stiff skin syndrome

Systemic Sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis: ▪ Scleroderma ▪ Progressive systemic sclerosis

Subtypes of cutaneous involvement: ▪ Diffuse ▪ Limited (includes CREST syndrome)

- ▪

An uncommon autoimmune connective tissue disease of unknown etiology

- ▪

Characterized by symmetric hardening of the skin of the fingers, hands and face that may generalize

- ▪

Raynaud phenomenon is common and digital ulcers may develop

- ▪

Internal organ involvement is frequent and affects the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart and kidneys

- ▪

Important to monitor for lung involvement because pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death

- ▪

Treatment focuses on internal organ manifestations; effective therapy for cutaneous sclerosis remains inadequate

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc, scleroderma) is an autoimmune connective tissue disease (AI-CTD) of unknown etiology that affects the skin, blood vessels and internal organs . The name systemic sclerosis is meant to convey the systemic nature of the disease, which has two major clinical subtypes: cutaneous limited and cutaneous diffuse . Limited SSc is characterized by fibrotic skin changes that are limited to the fingers, hands and face. In diffuse SSc, generalized cutaneous sclerosis is seen that usually begins in the fingers and hands but eventually extends to the forearms, arms, face, trunk, and lower extremities. Other entities that can lead to symmetric and widespread cutaneous induration include generalized morphea, eosinophilic fasciitis, scleromyxedema, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, scleredema, and chronic GVHD ( Table 43.1 ).

| MAJOR CLINICAL AND LABORATORY MANIFESTATIONS OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS AND OTHER SELECTED CONDITIONS CHARACTERIZED BY CUTANEOUS INDURATION | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic sclerosis | Morphea | Eosinophilic fasciitis | Scleredema | Scleromyxedema | NSF | Chronic GVHD | |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Raynaud phenomenon | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Symmetric induration | ++ * | − plaque-type and linear ± generalized | ++ * | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Sclerodactyly | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Facial involvement | + | − plaque-type and generalized + linear (en coup de sabre) | − | ± types I and II − type III | + | − | ± |

| Systemic involvement | ++ | − for plaque-type but ± for linear involving head (ocular, CNS) | + | − | ++ | + | + |

| Antinuclear antibodies | ++ | ± generalized and linear − plaque-type | − | − | − | − | ± |

| Anti-centromere antibodies | + limited | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibodies | + diffuse | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III | + diffuse | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | − | − | ± | + type II | ++ | − | − |

| Spontaneous remission | − | ++ plaque-type + generalized ± linear | ++ | ++ type I ± types II and III | − | ± † | − |

* May be preceded by edematous phase.

History

The first reported case of SSc in 1754 was a young Italian woman who developed progressive induration of her skin . From the clinical description, it is impossible to determine whether she had true SSc or another sclerodermoid disorder such as scleredema.

Epidemiology

SSc has a worldwide distribution and affects all races. The annual incidence and prevalence rates in the US are approximately 20 and 275 cases per million, respectively . Women are affected three to four times as often as men. Although SSc can occur in children and the elderly, onset is typically between the ages of 35 and 50 years. African-Americans have an earlier mean age of onset and a higher likelihood of diffuse disease . Approximately 1.5% of SSc patients have one or more affected first-degree relatives, representing a 10- to 15-fold higher risk of SSc in family members than in the general population . SSc is associated with significant mortality, with an overall 10-year survival of ~70% . Clinical features that predict a worse prognosis include male sex, African-American race, older age at diagnosis, internal organ involvement (especially pulmonary) at time of diagnosis, skin fibrosis affecting the trunk, and elevated ESR .

Pathogenesis

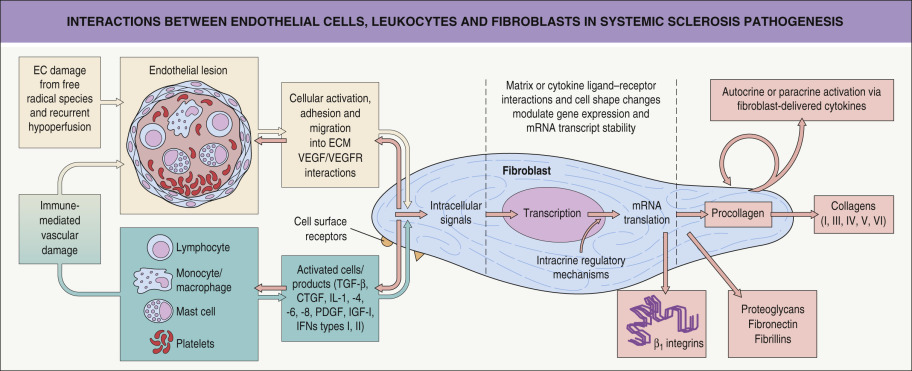

The pathogenesis of SSc is unknown. Key pathogenic abnormalities in the skin and internal organs are vascular dysfunction, immune activation with autoantibody production, and tissue sclerosis characterized by deposition of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins ( Fig. 43.1 ) .

Vascular dysregulation

Impaired angiogenesis is an early event in the pathogenesis of SSc . The blood vessels affected range from the smallest capillaries within the proximal nail fold to the large pulmonary arteries. Endothelial cell injury occurs early (before fibrosis is evident), based on changes seen by electron microscopy, such as perivascular leak and edema . Endothelial cell activation leads to increased expression of adhesion molecules and binding of circulating inflammatory cells. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (VEGFR) are elevated in the dermis in SSc .

Surrounding smooth muscle cells are also affected and have altered production of and responsiveness to vasoconstrictive (e.g. cold, endothelin) and vasodilatory (e.g. nitric oxide) factors. Structural abnormalities such as intimal proliferation lead to luminal occlusion hypoxia which induces synthesis of profibrotic cytokines, fibroblast activation, and collagen production . Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers are caused by reversible vasospasm as well as irreversible arterial damage with intimal proliferation and luminal obstruction. Scleroderma renal crisis and pulmonary artery hypertension are manifestations of large vessel dysregulation.

Immune dysregulation

Autoantibodies unique to SSc, in particular anti-centromere, anti-topoisomerase I, and anti-RNA polymerase III, are useful for diagnostic and prognostic purposes (see Ch. 40 ) . These three autoantibodies bind tissues of interest in SSc, as do anti-U3RNP (antifibrillarin), anti-Th/To, anti-U1RNP, anti-PM-Scl, and anti-Ku autoantibodies . The latter are rather rare and play a role in overlap syndromes.

Evidence of a direct pathogenic role for these autoantibodies includes complexes containing topoisomerase I autoantibody which, when bound to the surface of fibroblasts, have been found to stimulate monocyte adhesion and activation. In addition, anti-endothelial cell antibodies from SSc patient sera can trigger endothelial cell apoptosis. One group described stimulatory autoantibodies against the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor in SSc sera, which induced reactive oxygen species and expression of type I collagen by normal human fibroblasts . However, two subsequent studies were unable to confirm these findings .

Lymphocytic infiltrates, composed of both T and B cells, have been observed in the skin and lungs of SSc patients before the development of fibrosis. Oligoclonal T-cell expansion has been identified in lesional skin, indicating an antigen-driven response, and T cells demonstrate a Th2-predominant profile with increased production of profibrotic cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13. SSc patients also have expansion of naive B cells and chronic activation, but a decreased number, of memory B cells.

More recently, Th17 cells and IL-17 have been implicated in SSc, as have the innate immune system and types I (α,β) and II (γ) interferons. For example, elevated numbers of plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been observed in the blood and skin of SSc patients . In a proteome-wide analysis of five large cohorts, circulating levels of the chemokine CXCL4 were found to be significantly elevated (compared to controls), and the CXCL4 levels correlated with the presence and progression of pulmonary disease . The authors proposed CXCL4 as a biomarker to monitor for the development of lung disease in SSc patients. This recommendation awaits validation in prospective studies.

Extracellular matrix dysregulation

Sclerosis represents the final common pathway for tissue damage in SSc. There is excessive deposition of collagens, proteoglycans, fibronectin, fibrillins and adhesion molecules (e.g. β 1 -integrins), which sequester cytokines and growth factors (see Fig. 43.1 ). Attention has focused on transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). The latter is induced by TGF-β and may be responsible for maintenance of collagen synthesis.

Given the complex extracellular matrix changes seen in SSc , both the fibroblast and the myofibroblast have been a focus of investigation. There is evidence suggesting an inherent defect, an autocrine loop, or a hypersensitivity to growth factors in SSc fibroblasts. Alternatively, SSc fibroblasts may have a normal phenotype, but instead find themselves in an abnormal microenvironment with enhanced growth factors or ischemic mediators. The accumulation of collagen in SSc seems to be primarily the result of increased synthesis, rather than decreased degradation.

Clinical Features

Classification and diagnostic criteria

In 1980 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published preliminary criteria for the classification of SSc, which were updated in 2013 ( Table 43.2 ) . These classification criteria ensure the patient population being studied is well-defined and homogeneous, which is particularly important in rheumatic diseases where nonspecific and overlapping symptoms may lead to misclassification. As a result, classification criteria are stricter than the diagnostic criteria used for an individual patient. Nonetheless, for our purposes, they will be used interchangeably.

| ACR/EULAR CRITERIA FOR THE CLASSIFICATION OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Sub-item | Weight/score |

| Skin thickening of the fingers of both hands extending proximal to the MCP joints ( sufficient criterion) | – | 9 |

| Skin thickening of the fingers | Puffy fingers – or – Sclerodactyly | 2 4 |

| Fingertip lesion | Digital tip ulcers – or – Pitting scars | 2 3 |

| Telangiectasias | – | 2 |

| Abnormal nail-fold capillaries | – | 2 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension – or – Interstitial lung disease | 2 2 | |

| Raynaud phenomenon | – | 3 |

| SSc-related autoantibodies | Anti-centromere Anti-topoisomerase I Anti-RNA polymerase III | 3 |

In the 2013 classification scheme for SSc, the sole major criterion – skin thickening of the fingers on both hands extending proximal to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints – leads to a diagnosis of definite SSc (9 points) . If the patient does not meet this criterion, seven other minor criteria may be used to reach a diagnosis of SSc (see Table 43.2 ). These 2013 criteria have greater sensitivity (91%) and specificity (92%) compared to older criteria .

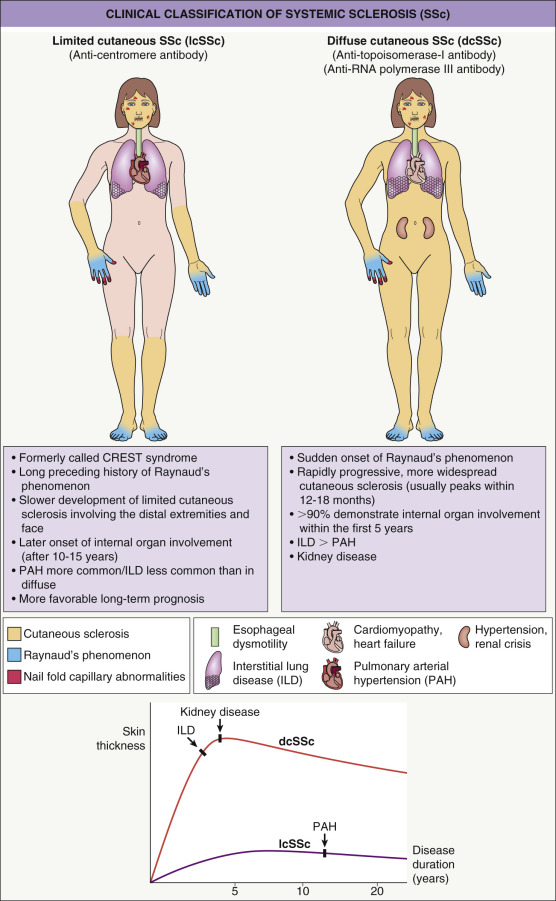

Based upon the degree of skin involvement, there are two major clinical subtypes ( Fig. 43.2 ): limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) and diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) . When the skin disease involves the distal and proximal portions of the extremities, the trunk and the face, it is considered diffuse cutaneous disease, but when the induration is limited to the distal extremities and face, it is considered limited cutaneous disease . Although both subtypes can have systemic manifestations, there are variable patterns and severity of internal organ involvement ( Table 43.3 ). Typically, diffuse SSc is associated with early internal organ involvement (within 5 years of disease onset) and a worse prognosis , whereas patients with limited SSc tend to develop internal involvement later in the disease and have a better prognosis.

| COMPARISON OF CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FEATURES OF DIFFUSE AND LIMITED SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diffuse SSc (%) | Limited SSc (%) | |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 90 | 99 |

| Finger swelling | 95 | 90 |

| Tendon friction rubs | 70 | 5 |

| Arthralgia | 98 | 80 |

| Proximal weakness | 80 | 60 |

| Calcinosis | 20 | 40 |

| Mat telangiectasias * | 60 | 90 |

| Esophageal dysmotility | 80 | 90 |

| Small bowel involvement | 40 | 60 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 70 | 35 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 10 | 30 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 15 | 10 |

| Renal crisis | 20 † | 1 |

| Sicca syndrome | 15 | 35 |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 90 | 90 |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 5 | 40 |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody | 20 | 5 |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III | 10 | 1 |

| Cumulative survival (5 years) | 80 | 90 |

| (10 years) | 70 | 80 |

* In addition, nail-fold capillary abnormalities are observed in >90% of SSc patients.

† Has decreased with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

The acronym CREST syndrome describes the clinical features in a subset of patients with lcSSc: c alcinosis, R aynaud phenomenon, e sophageal involvement, s clerodactyly and t elangiectasia. However, because not every patient has all five features, the term lcSSc is favored. Rarely, patients present with characteristic internal organ involvement, Raynaud phenomenon, abnormal nail-fold capillaries and positive serologies, but no cutaneous sclerosis. This clinical presentation is referred to as systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) and it behaves similarly to lcSSc.

Cutaneous features

Many patients with SSc experience an early edematous phase, which often features pitting edema of the digits ( Fig. 43.3 ). Digital pits are also a characteristic finding ( Fig. 43.4 ). The skin subsequently hardens and develops a taut, shiny appearance (indurated phase). Eventually, there may be gradual thinning of the skin (late atrophic phase). The fingers can develop flexion contractures and ulcers ( Fig. 43.5 ) while involvement of the face can lead to a beaked nose, microstomia and a more youthful appearance.

There are a number of cutaneous changes other than fibrosis in patients with SSc. Dyspigmentation in areas of sclerosis is commonly observed. Some patients develop diffuse hyperpigmentation, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas and sites of pressure. The “leukoderma of scleroderma” is characterized by localized areas of depigmentation with sparing of the perifollicular skin; this helpful diagnostic finding is sometimes referred to as the “salt and pepper” sign ( Fig. 43.6 ). Pigment may also be retained in the skin overlying superficial veins. This leukoderma favors the upper trunk and central face and may overlie uninvolved or sclerotic skin.

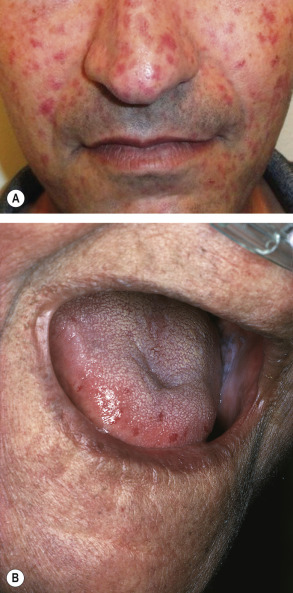

Telangiectasias are more common in patients with lcSSc but also occur in patients with dcSSc (see Table 43.3 ). The telangiectasias most often involve the face, lips and palms. These telangiectatic macules are matted or squared-off ( Fig. 43.7 ). Capillary abnormalities in the proximal nail fold are present in more than 90% of SSc patients and can be useful in supporting the diagnosis . Use of an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope may enhance appreciation of the abnormal nail-fold capillaries. A distinct pattern consisting of capillary loss (“drop out”) alternating with dilated loops is characteristic of SSc.

Calcinosis cutis most commonly develops on the extremities, usually near joints and in distal locations ( Fig. 43.8 ). In addition, the skin is often dry due to decreased sweating, and pruritus can be quite marked. Sclerotic skin may show diminished hair growth, but this is variable; hypertrichosis can also occur, particularly during the recovery phase. Overall, the cutaneous changes are extremely troublesome to patients with SSc. In a questionnaire-based study involving 300 patients with SSc, facial involvement and microstomia were the patients’ greatest concerns .

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by episodic vasospasm of the digital arteries resulting in white, blue and red discoloration of the fingers secondary to cold exposure . Raynaud phenomenon occurs in two settings ( Table 43.4 ). Primary Raynaud phenomenon (Raynaud disease) typically develops in adolescent girls and young women and is not associated with any underlying medical problems . Primary Raynaud phenomenon is common and estimated to affect 3% to 5% of the population. In contrast, secondary Raynaud phenomenon is uncommon and is associated with an underlying medical problem, including SSc ( Fig. 43.9 ; Table 43.5 ). An approach to differentiating primary from secondary Raynaud phenomenon is presented in Fig. 43.10 .

| CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FEATURES OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY RAYNAUD PHENOMENON | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Primary Raynaud | Secondary Raynaud |

| Sex | F : M 20 : 1 | F : M 4 : 1 |

| Age at onset | Puberty | >25 years |

| Frequency of attacks | Usually <5 per day | 5–10+ per day |

| Precipitants | Cold, emotional stress | Cold |

| Ischemic injury | Absent | Present |

| Abnormal capillaroscopy | Absent | >95% |

| Other vasomotor phenomena | Yes | Yes |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Absent/low titer | 90–95% |

| Anti-centromere antibody | Absent | 30–40% |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody | Absent | 20–30% |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | Absent | 10–20% |

| In vivo platelet activation | Absent | >75% |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree