Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Pranav Pancholi

Mahendra Pancholi

Ellen K. Roh

With over 19 million annual cases of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in the United States, it is important for the primary care provider to have a good understanding of the field of STDs. STDs have for a long time been a component of dermatology but with the advent of the era of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are often managed by infectious disease specialists. The subsequent sections will emphasize mainly dermatologic STDs but references will be made to other STDs as well for a comprehensive review.

The following diseases are classified as STDs:

Chancroid

Chlamydia

Donovanosis (granuloma inguinale)

Genital herpes

Genital human papilloma virus (HPV) infection (condyloma acuminatum)

Gonorrhea

Hepatitis B/C

HIV

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Molluscum contagiosum (in some cases)

Mycoplasma and ureaplasma urethral infections (not pneumonia)

Pubic lice and scabies

Syphilis

Trichomoniasis

The above list tries to cover most of the important causes of STDs. In many instances patients may present with signs and symptoms of just one STD, but a careful history and examination should be done to search for other STDs. Up to 23% of patients presenting for the evaluation of an STD have been found to have multiple infection types.

A general template for the workup in males and females is discussed below. The workup for an STD may vary depending on the history and physical examination—for example, in males practicing sex with males (MSM), tests for Hepatitis A and B antibodies should be included, so that the vaccines can be offered to patients with negative serologies. As with any STD the importance of patient education and subsequent testing of sexual partners cannot be overstated. Every effort must be made to reach out to these individuals to discuss abstinence, monogamy, and protective techniques. Baseline studies are summarized in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1 Baseline Evaluation for Suspected Sexually Transmitted Diseases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nonvenereal Skin Disease

|

Thomas is a 16-year-old boy who comes to see you with a complaint of an “STD.” He says that he noticed some warts on his penis. On further probing he denies any sexual intercourse but confesses that he saw them after he masturbated for the first time. He reports that they don’t seem to change in size or disappear. On examination, you notice circumferentially arranged, skin-colored papules on the corona and sulcus of the penis (Fig. 13-1).

Normal Anatomic Variants

Pranav Pancholi, Mahendra Pancholi, and Ellen K. Roh

Background

Genital lesions can be a cause of great alarm and anxiety in patients, especially when noticed after sexual intercourse for the first time or after sexual intercourse with a new partner. A good number of young men are obsessed with their genitals during puberty and will inspect their genitalia frequently. This can be a source of anxiety for the young adolescent who may be under the impression that he has been plagued by an STD.

Table 13-2 Normal Variants on Genital Skin | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Figure 13-1 Pearly penile papules. From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide to Common Skin Disorders, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009. |

Figure 13-5 Angiokeratoma of the vulva. From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide to Common Skin Disorders, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009. |

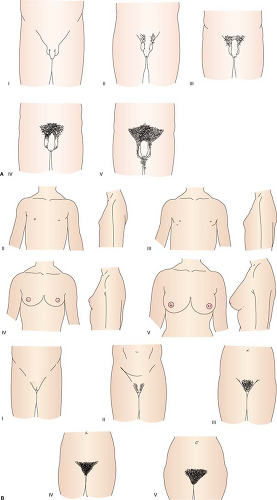

Familiarity with normal genital anatomy and physiology is essential to be able to recognize normal anatomic variants and processes. Patients often present with worries about their own genitals, such as size, shape, retractibility of the prepuce and the distribution of pubic hair, as well as questions about vaginal/penile discharge. The normal variants of genital morphology are listed in Table 13-2 (Figs. 13-1 to 13-5).

Nonvenereal Genital Lesions

Pranav Pancholi, Mahendra Pancholi, and Ellen K. Roh

Some individuals may harbor a myth that every genital lesion is a sexually transmitted disease. Most skin conditions may present themselves in the anogenital region, and it is important to be aware of their presentations so that a false diagnosis of an STD is not made. Many of the conditions that are found on the genitals are common dermatoses also found on other body sites. Three conditions should be highlighted in this section: lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and psoriasis. All of these conditions are inflammatory in nature, commonly present on the genitalia, and are not sexually transmitted.

Lichen planus and psoriasis are discussed in detail in Chapter 12. Psoriasis on the genitalia presents in similar fashion to other body sites, with erythematous scaling plaques (Fig. 13-6). It may involve the penis/scrotum or vulva, perianal skin, and gluteal cleft. In many cases, it is challenging to treat and is a significant cause of discomfort for the patient. Lichen planus presents with purple papules and plaques as well as whitish surface changes (Fig. 13-7) called Wickham’s

striae. In women, the vaginal mucosa may be involved, leading to a thin vaginal discharge. All women with suspected or confirmed lichen planus should have regular vaginal exams and intravaginal treatment for their lichen planus.

striae. In women, the vaginal mucosa may be involved, leading to a thin vaginal discharge. All women with suspected or confirmed lichen planus should have regular vaginal exams and intravaginal treatment for their lichen planus.

Figure 13-6 Penile psoriasis. From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide to Common Skin Disorders, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009. |

Figure 13-9 Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Image from Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999. |

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory condition of the penis or vulva of unknown etiology. It presents in middle age or older individuals, characteristically with atrophic hypopigmented patches/plaques on the genitalia most commonly. Other body sites may also be involved (Fig. 13-8). Symptoms generally are burning and itching, but the long-term scarring causes significant morbidity in some. In males, balanitis xerotica obliterans may cause both phimosis and paraphimosis in the male. In females, gradual scarring may lead to obliteration of the external anatomy (clitoris, labia minora) (Fig. 13-9), stenosis of the introitus, and involves the perineal body/perianal skin (Fig. 13-10). Chronic treatment with a potent corticosteroid is necessary.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

Jennifer K. Tan-Billet, Andrew A. Nelson, Pranav Pancholi, Mahendra Pancholi, and Ellen K. Roh

|

Jose is a 24-year-old who presents with a “swelling” on his penis that he noticed 2 weeks ago. He says that it does not bother him but his partner told him to get it checked. On further questioning he admits to having had multiple partners with whom he occasionally uses protection. On examination, you find a few unevenly distributed papular lesions that have a “cauliflower-like” appearance (Fig. 13-11). On application of 5% acetic acid, the lesions become whitish.

Background/Epidemiology

Condyloma acuminatum (CA) derives its origin from the Greek word “kondylos” meaning knob or knuckle. It is the most common STD with a 1% incidence in sexually active adults. The CDC reports that at least 50% of sexually active

adults are affected at some point in their lives. The risk of disease increases with the number of lifetime sexual partners. CA is associated with infections by the human papilloma virus (HPV). In the 1970s, the association between HPV infections and cervical cancer was first recognized. However, more recently, it has become apparent that certain specific “high-risk” HPV types are more closely associated with the development of cervical cancer.

adults are affected at some point in their lives. The risk of disease increases with the number of lifetime sexual partners. CA is associated with infections by the human papilloma virus (HPV). In the 1970s, the association between HPV infections and cervical cancer was first recognized. However, more recently, it has become apparent that certain specific “high-risk” HPV types are more closely associated with the development of cervical cancer.

Key Features

Condyloma acuminatum (genital warts) (CA) are wart-like lesions in the genital region caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.

Typically CA presents as soft exophytic growths in the groin and anogenital region.

CAs are caused by HPV infections. HPV types 16, 18, 31, and 33 are “high-risk,” and are associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. HPV types 6 and 11 are “low-risk” and are not associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer.

Common, highly prevalent sexually transmitted infection in young adults spread via intimate contact. It can be a manifestation of sexual abuse in young children.

Treatment consists of topical destructive therapy or immunomodulatory therapies. Lesions can be quite refractory to therapy.

A vaccine has been developed which helps to protect against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in HPV-naïve patients.

Pathogenesis

Similar to verruca vulgaris, CA is caused by infection with HPV. HPV infects the proliferating basal keratinocytes, causing upregulation of the cell cycle and dysregulated cellular proliferation. This results in the characteristic hyperkeratotic, exophytic lesions.

As mentioned, HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 are “high-risk” HPV types, associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. Of these types, HPV 16 and 18 are the most common cause of cervical cancer. It is not clear why these particular HPV types are oncogenic, although it is thought that when this HPV type DNA integrates into host DNA, it inhibits specific cellular proteins (E6 and E7 proteins). The E6 and E7 proteins normally regulate p53 and pRb genes; their inhibition results in dysregulated cell division and oncogenic potential.

Clinical Presentation

CA are typically soft, papillated exophytic growths located in the anogenital region (perineum and perianally); the external genitalia (labia, shaft of the penis, scrotum) (Fig. 13-11); or the adjacent areas (inguinal fold, mons pubis). They are usually skin-colored or pink and lack the thick hyperkeratotic surface of common warts. Early small lesions may be easily missed during a routine examination; larger lesions can be easily recognized. Many patients have subclinical infection and may be unaware that they can spread HPV. Patients with a pre-existing sexually transmitted infection are at increased risk for disease. Although nonsexual transmission is possible (such as during the passage through an infected vaginal canal during birth), when found in children it is imperative to look for signs of sexual abuse.

Soft, moist, pink- or flesh-colored papular eruptions with normal surrounding skin are typically present. However larger nodular growths or plaques may also be seen. In males, the shaft of the penis and the prepuce are the most commonly affected sites. The labia and the posterior fornix are the most commonly affected sites in women. Individuals participating in anal intercourse may have warts around the anal region.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings. However, if in doubt, 3% to 5% acetic acid can be applied with a cotton swab to look for whitening of the lesion. Aceto-whitening can also help to identify affected areas not easily apparent to the naked eye. If still uncertain, a biopsy can be performed for a more definitive diagnosis. A biopsy may also be indicated if there is any suspicion of malignant change. In women, a Papanicolaou smear should be performed. Anoscopy is recommended for patients with anal lesions. A workup for other STDs may be warranted depending on the clinical history and physical findings.

Differential Diagnosis

Condyloma lata, associated with secondary syphilis can be a diagnostic consideration. Serologic testing for syphilis is recommended in high-risk patients. When only a single lesion is present, a squamous cell carcinoma should be considered.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) in the genital area is also in the differential diagnosis with CA. While these lesions are spread by close contact they are not considered a STD in all cases. Lesions in the genital area of children are not necessarily transmitted sexually as MCs are easily spread by the patient’s own genital contact. If appropriate, abuse should be considered. In adults, lesions confined to the genitals are often spread by close physical contact. See Chapter 10 for a complete discussion of MC.

Diagnostic Methods

Many lesions can be recognized clinically. However, early lesions can be difficult to detect, particularly when they are located in the vagina

5% acetic acid can be applied to possible condylomatous lesions; if these lesions whiten with acetic acid, this supports the diagnosis of CA

Colposcopy can help visualize and identify the lesions in the vagina

A skin biopsy may be necessary to definitively identify the lesions. This is particularly true in young children, where the diagnosis of condyloma may be an indicator of sexual abuse

HPV testing via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be performed to differentiate high-risk versus low-risk HPV, which can be of critical importance for female patients and their possible risk of cervical cancer.

Therapy/Treatment

Many cases of CA are subclinical, with significant multifocal infection with HPV. As a result, high rates of recurrence are noted regardless of which therapeutic modality is utilized. Therapeutic options are broadly divided into locally destructive and immunomodulators.

Destructive therapies (local anesthesia should be used for several of these therapies)

Podophyllin/Podophyllotoxin: Podophyllin is a root extract that acts as a local cytotoxic agent. It is physician-applied weekly to bi-weekly and requires rinsing 4 hours following application to prevent systemic toxicity. Podophyllotoxin (podofilox) is a preferred, less toxic agent that is applied by patients. It is used BID for 3 days, which is then followed by a 4-day medication-free period prior to repeating the cycle 2 to 3 times. No rinse is required between each application of podophyllotoxin.

Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen): Often applied using an open-spray or cotton-tipped applicator for approximately 10 to 30 seconds to generate a 2- to 3-mm iceball around the lesion (with cooling duration of approximately 20 to 60 seconds). No clinical trials have compared cryotherapy with placebo for the treatment of genital HPV infection.

Trichloroacetic acid: 80% to 90% solution is used, resulting in keratinocyte necrosis. Repeated weekly application is performed. Severe burning and pain may result from therapy.

Electrocautery: Care should be taken, as HPV has been reported to be aerosolized following electrocautery.

Surgical excision: Particularly useful for large, disfiguring lesions or those lesions that impair bowel function. This is often a debulking procedure and may require adjuvant treatment with another destructive/immunomodulatory agent.

Immunomodulators

Imiquimod: Stimulates toll-like receptors 7 and 8, stimulating production of inflammatory cytokines to kill HPV-infected cells. Patients may apply 5%

cream three times weekly until there is clearance or for a maximum of 16 weeks. Patients with HIV/AIDS may require up to 20 weeks of treatment,

Interferon and bleomycin: Intralesional forms of these agents are sometimes used as second-line agents for recalcitrant lesions. However, these injections can be painful for patients.

Prevention

Safe sexual practice is key in preventing CA, as skin-to-skin transmission is the main route of transmission. Male latex condoms confer some protection, but skin-to-skin transmission may still be possible. In 2006, a vaccine (Gardasil®) was approved for use in female patients between the ages of 9 and 26. The vaccine protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 and is most effective if administered prior to initial engagement in sexual activity. HPV 6 and 11 have been shown to cause approximately 90% of all cases of benign CA. HPV 16 and 18 are associated with approximately 70% of all cervical cancers. Thus, this vaccine not only protects against the high-risk HPV types, but also the most common low-risk HPV types. The vaccine requires three injections over a 6-month period. Common side effects include injection site pain, bruising, fever, vomiting, and syncope. While the vaccine can help prevent primary infection in HPV naïve patients, it does not have a role in the treatment of patients previously infected with HPV.

“At a Glance” Treatment

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen: the wart is frozen for 5 to 10 seconds with a 2- to 3-mm margin, left to thaw and then the procedure is repeated a second time.

5% imiquimod (Aldara) cream used three times weekly for up to 16 weeks.

Podofilox 0.5% gel is a treatment option that can be applied by the patient at home. It is to be used twice daily for 3 days, with a break for 4 days and the repeated. Four such cycles may be carried out.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree