Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

Nicholas J. Ahn

William H. Peranteau

DEFINITION

Usually benign extragonadal germ cell tumor that develops prenatally, involving the coccyx with various degrees of pelvic and intra-abdominal involvement.

It is the most common congenital neoplasm found in fetuses and neonates.

Between 11% and 35% of the tumors may contain malignant elements such as yolk sac tumor or embryonal carcinoma.1

Large or solid tumors may lead to poor clinical outcomes due to high-output cardiac failure, hydrops fetalis, tumor rupture, or internal hemorrhage.2

Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment but has associated morbidities such as problems with micturition, defecation, or cosmetic dissatisfaction up to 40% to 50%.3 Large tumors with significant pelvic/intra-abdominal involvement have the most significant risk for urologic and anorectal complications.4

ANATOMY

All sacrococcygeal teratomas (SCTs) involve the coccyx but are classified into four categories according to the location and extent of the tumor—the Altman Classification Scheme.5

Type I: primarily external with a small presacral component

Type II: external with intrapelvic extension

Type III: primarily pelvic and intra-abdominal with external component

Type IV: completely intrapelvic with no external component

PATHOGENESIS

SCTs are thought to originate from the primitive knot (also known as Hensen node), where the three germ cell layers start to form.

SCTs may be cystic, solid, or a mix of both. Solid tumors tend to be more vascular and are associated with an increased risk of high-output cardiac failure, hydrops fetalis, tumor rupture, hemorrhage, and fetal demise.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The majority of the lesions are now diagnosed by the time of birth as early as 18 to 19 weeks of gestation due to advancement in antenatal imaging.

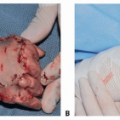

Type I to III lesions that are not diagnosed prenatally are identified at birth by an obvious protruding mass originating from the sacral region.

A rectal exam must be performed to assess the degree of intrapelvic extension of the tumor, especially for tumors that were diagnosed postnatally.

Rarely, some type IV lesions can go undiagnosed until the child is up to 4 years of age and present with compressive symptoms of the bladder or rectum, such as urinary retention, obstruction, or constipation.

IMAGING

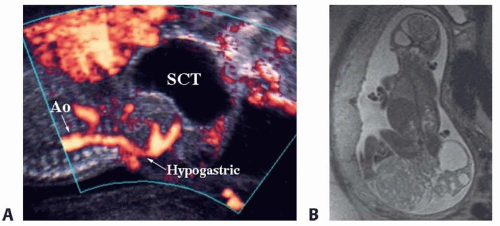

Most SCTs are diagnosed prenatally at the time of approximately 20-week gestation fetal anatomy ultrasound. If diagnosed, the mother and fetuses should be referred to a high-volume multidisciplinary fetal diagnosis and treatment center where a high-resolution fetal ultrasound will be performed to assess the anatomical extension of the tumor and the characteristics of the mass (solid, cystic, vascularity) (FIG 1A).

Ultrafast fetal MRI is used as an adjunct to ultrasonography to better assess the SCT, including the pelvic or abdominal extension of the tumor and its involvement with surrounding structures such as the colon, urinary tract, vagina, hip, and especially the spine (FIG 1B).

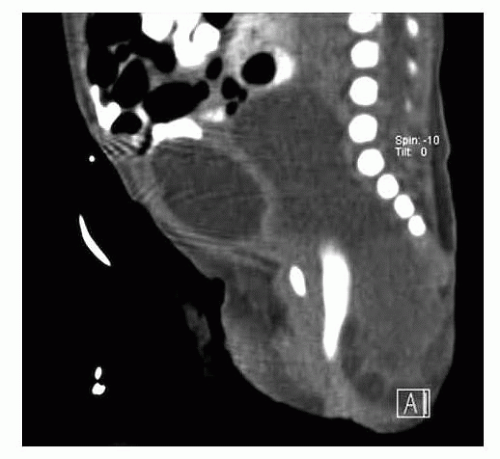

After birth, hemodynamically stable infants may undergo a CT scan or MRI to assess the extent of the tumor for preoperative planning (FIG 2).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Meningocele

Lymphangioma

Enteric duplication cyst

Dermoid cyst

Retrorectal hamartoma

Meconium pseudocyst

Tail remnant

Lipoma

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Fetuses with external tumors that are larger than 5 cm, predominantly solid, or have a significant vascular supply should be delivered by cesarean delivery to decrease the risk of catastrophic bleeding or tumor rupture.

If the patient is stable, the tumor can be resected within the first week of life.

CBC, type and screen, and cross-match must be performed in anticipation of surgery.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and β-HCG levels should be obtained prior to surgery.

CT scan or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast should be performed as discussed above in stable patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree