Abstract

Rhinoplasty is commonly acknowledged as the most demanding and difficult of plastic surgical procedures. The demands of rhinoplasty in the aging patient are no different. Regardless of patient age, the principles of structure rhinoplasty remain constant: surgical manipulation of the nasal construct causes weaknesses susceptible to scar contracture. Augmentation is required to withstand the distorting forces of tissue healing. However, certain functional and aesthetic goals of the aging patient must also be taken into account in a procedure that involves tissue reorientation and augmentation, with careful attention to long-term surgical outcome consideration while adhering to this philosophy.

Keywords:

Rhinoplasty, Structure rhinoplasty, Aging nose, Aging patient, Ptotic tip, Nasal valve collapse, Acute nasolabial angle

Personal Philosophy

Rhinoplasty at any age is a complex operation that requires precise preoperative diagnosis to select the appropriate surgical technique. Owing to variations in nasal anatomy and aesthetic expectations, no single technique is appropriate for all patients. Each rhinoplasty patient presents the surgeon with a diversity of nasal anatomy, contours, and proportions that requires a series of organized maneuvers tailored to the patient’s functional and aesthetic needs. In addition, the surgeon must also be skilled at manipulating and controlling the dynamics of postoperative healing to attain an optimal long-term result.

Nasal Analysis

Over time the nasal structure and external contour are influenced by a multitude of genetic and environmental factors. Children typically have a convex nasal dorsum that progresses to a straight dorsal line. In the aging patient, the nasal dorsum may become increasingly convex. In combination with general lengthening of the nose, there may be relative lengthening from ptosis of the nasal tip or exaggeration of an existing dorsal hump . In addition, nasal function in the aging patient may also decline, with compromise of the nasal airway at both internal and external nasal valves.

The nasal bones may become brittle and more readily fractured with aging . Dorsal hump reduction must be executed with precision to minimize irregularities that may be visible through the thinner skin of the aging patient . Judicious and precise osteotomies are required to avoid excessive narrowing of the bony vault or comminuted fractures of the nasal bones. Wide periosteal elevation is not recommended in the aging patient. To avoid loss of periosteal support, periosteal elevation should not extend to the site of intended lateral osteotomies .

As the most significant changes over time occur in the upper and lower lateral cartilages, careful preoperative evaluation of the size, shape, angulation, and orientation of each cartilaginous component of the nose is essential in surgical planning for aesthetic and functional rhinoplasty. The scroll region is a fibrous union at the cephalic margin of the lower lateral crura, which connects these lateral cartilages . With aging, the upper and lower lateral cartilages begin to separate and fragment . This may result in the collapse of the internal nasal valve and lateral wall. As one ages, the middle nasal vault will tend to collapse as the upper lateral cartilages move inferomedially. Loss of support of the medial crura and stretching of the fibrous attachments from the posterior septal angle and nasal spine to the medial crural footplates result in their posterior movement and retraction of the columella . This retraction may be further compounded by resorption of the fat pad of the medial crura and premaxilla in the aging patient .

The lower lateral cartilages provide the main support for the nasal tip. The caudal margin of the lateral crura should be oriented slightly superior to the cephalic margin. Loss of this relationship may lead to a poorly defined nasal tip and pinched ala. In addition, the external nasal valve may be compromised due to loss of lateral wall support . Diminished support of the lateral and medial crura as well as disunion of the upper lateral cartilages may ultimately create a ptotic nasal tip and increasingly acute nasolabial angle . Preoperative assessment of the base view of the medial crural footplates is essential in evaluating the stability of the nasal base. Long and strong medial crural footplates that extend to the nasal spine will provide significant support and minimize loss of projection in the long-term result .

The aging patient is also subject to changes in the properties of the skin. Loss of elasticity and dehydration of the skin diminishes the skin’s pliability. Furthermore, resorption of subcutaneous fat deposits and soft-tissue atrophy contribute to skeletonization of nasal bone step-offs or sharp angulations of the lower lateral cartilages . In the aging patient, the skin’s ability to contract and redrape over a reduced bony and cartilaginous structure is diminished. On rare occasions direct excision of skin from the nasal dorsum or supratip can be performed to aid redraping. In this patient population external incisions can be performed with less likelihood of unfavorable scar .

Preoperative Assessment

As with any facial aesthetic surgery patient, preoperative assessment must address anatomic, functional, and psychological factors . The surgeon must discuss motivation and aesthetic goals with the patient. Not infrequently, older patients do not wish to look dramatically different and elect for more conservative changes. The aging patient has developed a self-image over many years and must be counseled on the proposed changes.

Reviewing standard preoperative photographs with the patient is critical during surgical consultation. This may aid in eliciting the patient’s preferences, which may stem from an established self-image or from a cultural background. Computer imaging has become an increasingly common tool to facilitate discussion between the surgeon and patient about aesthetic goals and surgically feasible results. It is important to remind the patient that the computer-enhanced images are not a guarantee of the exact postoperative result, but provide the surgeon with a better understanding of the patient’s aesthetic goals.

A thorough medical history and physical examination are necessary in the aging patient, as they are more likely to have co-morbid medical conditions. Collaboration with the primary care physician is a prerequisite prior to surgical scheduling. Medications that interfere with hemostasis should be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to surgery.

Surgical Technique

Preoperative Considerations

Selection of the surgical approach must take into consideration both the operative objectives and the surgeon’s experience. If the patient requires only conservative volume reduction of the lateral crura or dorsal hump reduction, a nondelivery approach with cartilage splitting or a retrograde approach will suffice. However, when more complex nasal tip work or middle-vault reconstruction is required, an external approach or delivery of bilateral chondrocutaneous flaps is preferred. The surgeon should select the least invasive approach possible to avoid disruption of the nasal support mechanisms and maximize the functional and aesthetic result for each individual nose.

The technical approach for the aging nose is in a top-down fashion: setting the dorsal height first, aligning the nasal bones, addressing the middle vault, securing the nasal base, and contouring the tip last. These structural changes should be both conservative and in harmony with the aging patient’s other facial features.

The External Approach

The patient is first injected with 1% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine in the nasal tip, between the domes, down to the columella, at the planned marginal incision sites, and along the lateral walls of the nose. Additional injections to the nasal septum facilitate identification of the amount of cartilaginous septum available for grafting material. An inverted V columellar incision is then marked midway between the base of the nose and the top of the nostrils. A transcolumellar incision is executed with a No. 11 blade. Care must be taken to avoid damaging the caudal margin of the medial crura. Marginal incisions are then made along the caudal border of the lateral crura. Columellar incision extensions are created bilaterally with a No. 15 blade.

Once the incisions are complete, angled Converse scissors are used to sharply elevate the skin off the medial crura. Sharp dissection preserves the subdermal plexus, which improves hemostasis and minimizes postoperative edema. It is important to keep particular attention to preserve the soft tissue triangles and maintain a cuff of tissue separating the marginal incision from the alar rim. Using three-point retraction, the surgeon continues to raise the skin envelope sharply, advancing the dissection laterally to expose the lateral crura. In the aging patient, subcutaneous fat and muscle should be preserved in order to avoid noticeable irregularities of the underlying bone and cartilage through the thinner skin of the aging nose. The anterior septal angle is identified, with exposure of the middle nasal vault in the midline. Sharp dissection is continued to the rhinion, which may be followed by blunt subperiosteal dissection of the skin off the nasal dorsum up to the nasion if profile alignment is necessary. If a radix graft is planned, then a narrow pocket should be dissected in the midline over the radix. This narrow pocket will prevent shifting of a radix graft.

After completing the dissection of the nasal framework, the surgeon surveys the nose and plans the anticipated grafts necessary to structurally support the nose for the anticipated result.

Profile Alignment and Narrowing the Nose

Successful management of the bony nasal vault of the aging patient involves conservative dorsal hump reduction, avoidance of dorsal irregularities, and alignment of the nasal bones without excessive narrowing. Because the nasal bones in the aging patient can be thin and brittle, careful manipulation of the bony vault must be exercised in order to avoid comminuted fractures or excessive narrowing of the bony vault. Green-stick fractures of the nasal bones are acceptable in the aging patient, as this type of fracture is less likely to comminute or become excessively displaced medially.

For dorsal hump reductions, a Rubin osteotome can be used to address 80% of the hump. The residual hump can be managed with a fine rasp. With larger dorsal humps, wide undermining of the overlying skin soft-tissue envelope is necessary to accommodate for reduced skin elasticity and less rapid shrinkage and redraping. In patients with a deep nasofrontal angle, small crushed cartilage and soft-tissue radix grafts can be placed above a dorsal hump to create a straight profile. The nasal starting point should be located at the level of the superior palpebral fold in female patients, with a slightly higher location in male patients. In some cases, dorsal hump reduction can be avoided if the profile can be improved with a combination of radix grafting and appropriate increase in nasal tip projection.

Following profile alignment in the aging patient, lateral osteotomies can be performed to address excess width or deviation of the nasal bones. Using the smallest osteotome (2 or 3 mm) minimizes trauma and bleeding when fracturing the thin bone. In most aging patients, medial osteotomies can be avoided as the bones are readily fractured. Because the thinner skin of older patients show the smallest dorsal irregularity, special care must be taken to ensure a smooth dorsum. Additional rasping or soft tissue onlay may be required to prevent visible irregularities.

Septal Surgery

The goals of septal surgery in the aging patient is similar to other patients: correction of deviation obstructing the nasal airway and harvest of grafting material. The septum may be accessed via multiple approaches. When taking a less invasive approach, a Killian incision is preferred because of its excellent exposure without compromise of the support attachments between the medial crural footplates and the caudal septum. A hemitransfixion incision can be used if exposure of both sides of the caudal septum is required. The hemitransfixion or full transfixion incision can sometimes lead to a loss of support due to disruption of some of the attachments between the medial crura and caudal septum. In some patients, it may be necessary to dissect between the medial crura to access the caudal septum. Patients with a deviated caudal septum may benefit from this approach to allow correction of the deformity. Other patients with poor tip support could benefit from stabilization of the nasal base through this approach.

When performing septal surgery in the aging patient, dissection of the mucosal flaps should be limited because the mucoperichondrium is thinner and susceptible to dryness. The correct plane of dissection, deep to the perichondrium, is critical to flap integrity. It may be preferable to raise a mucoperichondrial flap on only one side of the septum to preserve the vascular supply of the contralateral side. A substantial L-shaped septal strut should be preserved to support the lower two-thirds of the nose. We prefer to leave at least a 1.5-cm caudal and dorsal strut for support. Extra cartilage should be left at the osseocartilaginous junction to avoid loss of dorsal septal support and disruption of the dorsal septum from the ethmoid bone at the “keystone” area. The surgeon should be aware that the septal cartilage may be partially calcified in the aging patient, which leaves the surgeon with less cartilage for grafting. After completion of the septal surgery, a running 4-0 plain gut mattress suture is used to approximate the mucoperichondrial flaps and prevent fluid collection and hematoma formation.

Narrowed Middle Vault

In some older patients, an excessively narrow middle nasal vault can result when weak upper lateral cartilages collapse inferomedially. Significant cartilage migration may also result in collapse of the internal nasal valve. These patients experience improvement in their nasal airway obstruction while performing the Cottle maneuver or with lateralization of the lateral nasal wall with an instrument. To correct this deformity, the surgeon can apply bilateral spreader grafts between the dorsal margin of the nasal septum and the upper lateral cartilages . These grafts are rectangular in shape and measure approximately 5 to 15 mm in length, 3 to 5 mm in width, and 1 to 2 mm in thickness.

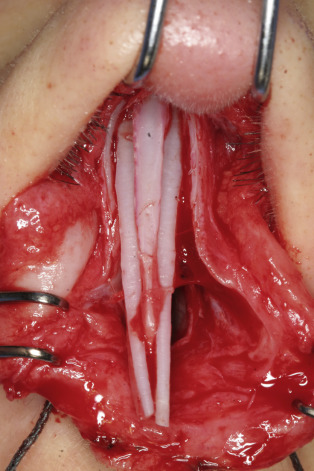

Spreader grafts can be applied via an endonasal approach into precise submucosal tunnels or may be applied directly between the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal septum via the external rhinoplasty approach . In the external rhinoplasty approach, the upper lateral cartilages are freed from the nasal septum after the middle nasal vault is exposed. The rectangular spreader grafts are then applied between the upper lateral cartilages and septum, and sutured into place with 5-0 polydioxanone (PDS) mattress suture ( Fig. 26.1 ). With incorporation of the upper lateral cartilages into the suture, the middle nasal vault width is set and inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages is avoided. Care must be taken to not create excess width to the middle vault. Patients with short nasal bones are at higher risk of collapse and will need thicker and longer spreader grafts. If possible, the surgeon should try to avoid dividing the upper lateral cartilages from the septum in order to preserve native middle-vault support in the older patient. Thus, if dorsal hump reduction is not needed in the aging patient, the spreader grafts may be placed into submucosal tunnels with preservation of the attachment of the upper lateral cartilages to the septum regardless of approach. In many older patients with a functional deficit at the internal nasal valve and lateral wall, spreader grafts will be insufficient and additional valve-supporting grafts should be used.