Rheumatoid Arthritis, Rheumatic Fever, and Gout: Introduction

|

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory autoimmune disease that is characterized by a debilitating chronic, symmetric polyarthritis with significant extra-articular manifestations, which include rheumatoid nodules, pyoderma gangrenosum, granulomatous dermatitis, vasculitis, and internal organ involvement. The disease process is often progressive, resulting in limitation of joint function. Ultimately, there may be a resultant decline in functional status, possibly leading to premature death. Permanent remission is unusual.

Rheumatoid arthritis has an annual incidence of approximately 0.4 per 1,000 in females and 0.2 per 1,000 in males, with a prevalence of approximately 0.4% to 1% of the adult population in diverse populations worldwide.1–3 Approximately 70% of patients follow a chronic disease course with exacerbations and remissions; 25% have intermittent disease with brief attacks of inflammation followed by remissions; approximately, 5% have an aggressive, malignant form with multiple extra-articular manifestations.4 RA has a peak onset at 50 years of age.1,2

The exact etiology of RA remains unknown. Genetics plays at least some role in the development, severity, and outcome of the disease in certain patients.5 Furthermore, an association between extra-articular disease and HLA-DR1 and -DR4 genes has been noted in some populations.6

Mechanical stress on joints may initiate an inflammatory response creating an imbalance between the rapid response to trauma and the need to protect self from damage. Patients with seropositive RA (positive rheumatoid factor) have circulating and tissue-bound immune complexes. B cells produce autoantibodies in some RA patients. After binding to antigen, these autoantibodies result in complement fixation and recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, which result in joint destruction. Possible antigens in RA include heat shock proteins, collagen, and cyclic citrullinated peptides.7 Indeed, antibodies to several citrullinated peptides are enriched in the joints of patients with RA.8

Patients with negative rheumatoid factor (seronegative RA) may not create autoantibodies, but other immune mechanisms are involved. This theory led to the recognition that T cells are important players in the etiology of this disease. In the SKG mouse model, autoreactive T cells are preferentially selected, leading to inflammatory arthritis similar to RA. T cells also activate other cells via cytokines, including osteoclasts, which play a major role in the bone resorption seen in RA. Effector cytokines of the T cell include interferon-γ, interleukin 1, interleukin 17, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), many of which have been, or are being, used as therapeutic targets to treat RA.4,7

Lastly, joints have unique anatomic and physiologic qualities that render them targets for immune and inflammatory assault. Cartilage is subject to repetitive mechanical stress, retains antigens and proinflammatory cytokines, and has a limited capacity for regeneration. Only two groups of enzymes found in the joint are capable of degrading native type I and II collagen fibrils: (1) cysteine cathepsins and (2) matrix metalloproteinases.9

RA often begins with general constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, anorexia, vague musculoskeletal complaints, and generalized weakness. It may be weeks or months before the characteristic synovitis presents. It is in these early stages that definite diagnosis is most difficult, despite a thorough patient evaluation. However, early diagnosis and treatment are essential because most of joint damage is thought to occur early in the disease process. The American College of Rheumatology has guidelines for the diagnosis of RA (Table 160-1).10 For a patient to be diagnosed with RA, four of the seven criteria must be present, and the first four criteria listed must be present for at least 6 weeks. Extra-articular manifestations may help to delineate the disease process early and may signify a more serious disease process requiring the initiation of aggressive therapy.11,12 Several conditions can mimic RA, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of early disease: viral syndromes (especially parvovirus B19, rubella, hepatitis B and C), polymyalgia rheumatica, remitting seronegative symmetric synovitis with pitting edema (RSSSPE), palindromic rheumatism, adult Still’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis.13

Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around the joints, lasting at least 1 hour before maximal improvement |

Arthritis of three or more joint areas | At least three joint areas simultaneously afflicted with soft-tissue swelling or joint fluid observed by a physician. The possible areas are (right or left): PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints |

Arthritis of hand joints | At least one area swollen in a wrist, MCP, or PIP joint |

Symmetric arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas on both sides of the body (bilateral involvement of PIP, MCP, or MTP acceptable without perfect symmetry) |

Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules over bony prominences or extensor surfaces or in juxta-articular regions (observed by a physician) |

Serum rheumatoid factor | Abnormal amount of serum rheumatoid factor by any method while the result has been positive in 5% of control subjects |

Radiographic changes | Erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to the involved joints |

The articular manifestations of RA relate to an inflammatory synovitis that can affect the synovial lining of joints, tendons, and bursae. Synovial inflammation usually results in warmth but not erythema of the affected area. There is significant pain in association with stretching of the joint capsule. Hand and foot involvement forms the basis of the disease in most patients. Although the initial manifestations in the hand may be asymmetric, the clinical course subsequently takes on a symmetric and diffuse pattern. There is a characteristic involvement of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and metacarpophalangeal joints with sparing of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. The pattern of joint involvement is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Chronic inflammation may result in irreversible structural damage of the joint, including cartilage destruction and bony erosion. Late structural deformities may result from soft-tissue contractures or from bony ankylosis. Characteristic deformities include radial deviation of the hand with ulnar deviation of the digits, the “swan neck” deformity from hyperextension of the PIP joint and compensatory flexion of the DIP joint, and the boutonnière deformity from flexion contracture of the PIP joint and extension of the DIP joint. Similar structural deformities can occur in the feet, and all can be debilitating. Involvement of the thoracic and lumbar spine in RA is exceptional. Although the shoulder joint is often affected, it is soft-tissue structures, which include the rotator cuff tendons and muscles and the subacromial bursa that are usually involved in the patient’s symptomatology.

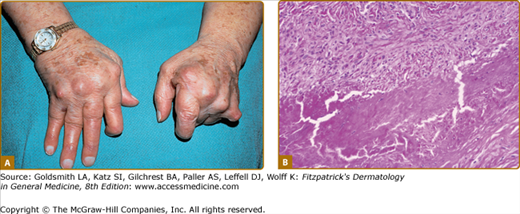

Extra-articular manifestations occur in more aggressive or extensive forms of RA.11,12 The most common dermatologic finding in RA is the rheumatoid nodule. The classic rheumatoid nodule is a subcutaneous nodule that occurs in approximately one-fourth of patients with RA (Fig. 160-1A). More than 90% of patients with rheumatoid nodules have seropositive RA. The usual location is over pressure points such as the olecranon, the extensor surface of the forearms, and the Achilles tendon; but they have been described in almost every location, including viscera.12 The main histologic findings (see Fig. 160-1B) are palisaded granulomas in the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissues with fibrinoid degeneration of collagen, a multitude of neutrophils, and neutrophilic dust, with surrounding fibrosis and proliferation of vessels. The main differential diagnoses histopathologically include subcutaneous granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, foreign body or infectious granulomatous reaction, and epithelioid sarcoid.14

Though rheumatoid nodules are benign, they can lead to complications, including ulceration, infection, joint effusion (rheumatoid chyliform bursitis), and fistulas (fistulous rheumatism). All conditions may lead to the need for surgical excision.12

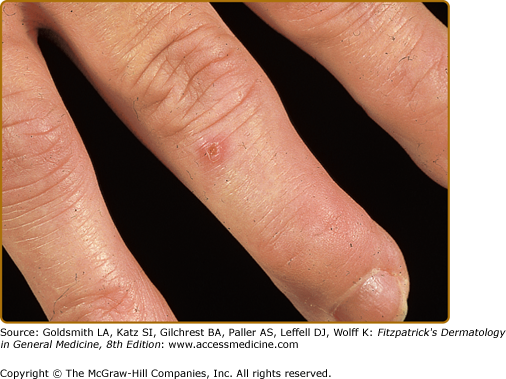

Rheumatoid vasculitis has an estimated annual incidence of less than 1%, most often affects patients with seropositive disease, and is believed to affect 1 in 8 males with RA, versus 1 in 38 females.15 A study of 30-year cumulative incidence of extra-articular manifestations, major cutaneous vasculitis occurred in 5.1% of the study population.16 Small- to medium-sized vessels are primarily affected, often with associated peripheral neuropathy (including motor), digital gangrene, nail fold infarcts, and palpable purpura (see Chapter 163 and 164).12,17 Some patients may have nail fold telangiectasias, with minute digital ulcerations or petechiae and digital pulp papules (Bywaters lesions) (Fig. 160-2). These papules are a manifestation of mild vasculitis and typically occur without systemic signs of vasculitis. Histopathology of skin biopsy specimens usually shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis with neutrophilic infiltration of the vessel wall, fibrinoid necrosis, and hemorrhage without palisaded granulomatous reaction.14 Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis mostly involves postcapillary venules and may affect arterioles and larger vessels of the viscera, heart, and central nervous system. The spectrum of clinical lesions reported in rheumatoid vasculitis is wide and varies with the size and location of the vessels involved and with the extent of the disease (see Chapters 163 and 164). Unfortunately, the presence of vasculitis, especially at the onset of the disease, portends a poor outcome.18 Vasculitis, along with certain other extra-articular manifestations of RA (pericarditis, pleuritis, amyloidosis, and Felty syndrome), are associated with a diminished lifespan.16 Rheumatoid vasculitis can present as lower-extremity ulcers; however, pyoderma gangrenosum (see Chapter 33) should be suspected if deep liquefying ulcers with a characteristic purple, undermined border occur in patients with RA. The ulcers may occur at any site but are most common on the lower extremities and abdomen. Pyoderma gangrenosum occurs more frequently and more severely in females and may take years to heal. Leg ulcers may also appear in patients with Felty syndrome, a combination of chronic RA, hypersplenism, and leukopenia (Fig. 160-3).12 In some instances, the ulcers of Felty syndrome exhibit the same morphologic characteristics and behavior of pyoderma gangrensoum ulcers, suggesting that these ulcers are not necessarily a manifestation of rheumatoid vasculitis.

Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis is a very rare cutaneous manifestation in patients with severe RA. First described by Ackerman in 1978, these lesions are usually chronic, erythematous, and urticaria-like plaques and papules that are sharply marginated (Fig. 160-4A). Histopathologically, these lesions have a dense infiltrate of neutrophils without leukocytoclasia, in the setting of a mixed infiltrate and papillary edema (see Fig. 160-4B).14 It may be difficult to differentiate rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis from acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome) (see Chapter 32). Some authors accept palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis as a histologic finding consistent with rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis.19 However, in the absence of granuloma formation, it seems reasonable to separate rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis from multiple named entities, which would seem to be now included under the term interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.

Figure 160-4

Rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis. A. Lesions are erythematous urticarial papules often coalescing into plaques in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. B. Histopathologically, there is an interstitial mixed dermal infiltrate predominated by neutrophils without leukocytoclasis. This is often accompanied by papillary edema.

Other vasculitis syndromes, such as erythema elevatum diutinum (see Chapter 165) and livedo vasculitis (segmental hyalinizing vasculitis), have also been described in patients with RA. Skin manifestations such as palmar erythema, erythromelalgia, autoimmune bullous diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (see Chapter 60), yellow nail syndrome (see Chapter 89), erythema multiforme (see Chapter 39), erythema nodosum (see Chapter 70), and urticaria (see Chapter 38) also have been reported in patients with RA.20

Low-dose methotrexate, often used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, may precipitate erythema and enlargement of preexisting rheumatoid nodules, known as accelerated nodulosis.21 Regression of these changes is expected when the methotrexate dose is decreased or discontinued. A second reaction to methotrexate has also been reported as a syndrome of clustered, erythematous, indurated papules arising most commonly on the proximal extremities and buttocks. This has been reported not only in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but also in association with other diseases as well, especially collagen vascular diseases.22,23 In rare instances, some lesions may develop erosions or surrounding livedo. The histologic pattern seen in the popular eruption is that of a mostly histiocytic infiltrate arranged interstitially between collagen bundles in the dermis, intermixed with a few neutrophils. Small rosettes of histiocytes may surround thick collagen bundles in the reticular dermis. Yet another possible cutaneous complication of methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis is the development of Epstein–Barr virus-associated multifocal cutaneous lymphoproliferative disease, which may regress on discontinuation of therapy.24

A histologically related eruption of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been described in association with a number of disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis.23 Cutaneous lesions consist of linear slightly red or skin-colored cords, most often extending from the upper back to the axillae.23,25 Histopathologic findings include a dense, diffuse infiltrate of histiocytes arranged in a band-like configuration in middle or deep reticular dermis. There may be foci of basophilic collagen surrounded by palisaded histiocytes. These cells may also exhibit large and pleomorphic nuclei, and scattered mitotic figures are readily seen. Neutrohils and eosinophils are present, most notably in areas of degenerated collagen.

Indurated erythema, livedo-like erythema, and papules over the elbows have been reported as clinical findings of intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis in rheumatoid arthritis.25

In addition to systemic vasculitis, which can affect numerous organ systems, there are multiple nondermatologic extra-articular manifestations of RA. Table 160-2 lists the more common ones.

Type | Manifestations |

|---|---|

Ocular | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, scleritis, episcleritis, scleromalacia |

Renal | Amyloidosis and vasculitis |

Hematologic | Anemia, thrombocytosis, lymphadenopathy, Felty syndrome |

Neurologic | Entrapment neuropathy, cervical myelopathy, mononeuritis multiplex (vasculitis), peripheral neuropathy |

Lung | Pleural effusions, pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiolitis obliterans, rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis |

Cardiac | Pericarditis, premature atherosclerosis, vasculitis, nodules, aortic root dilatation |

Consider

Rule Out

|

There is no one specific histologic, radiographic, or laboratory test that conclusively permits the diagnosis of RA. Rheumatoid factor, an autoantibody that reacts with the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG), is found in sera of 85% of patients with RA. Rheumatoid factor should not be used as a definitive screening tool because it can be found in other disease processes (sarcoidosis, liver diseases, pulmonary fibrotic processes, and cryoglobulinemia). It is also found in approximately 5% of the unaffected population.17 A false-positive rheumatoid factor can be caused by many factors, including chronic bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis, tuberculosis, and Lyme disease, as well as by viral diseases such as rubella and infectious mononucleosis.26 Anticitrullinated protein antibodies have been shown to be a more specific marker than rheumatoid factor, particularly in early disease where specificity ranges from 94% to 100%, compared to 23% to 94% for rheumatoid factor, with roughly equivalent sensitivities.3

Because the exact cause of RA is unknown, treatment has been directed against various components of the inflammatory process. No single therapy is the treatment of choice. In the past, most patients with early disease were started on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs until joint erosions were evident.

These medications are useful to alleviate symptoms. They do not alter disease progression.

Furthermore, new understanding of disease mechanism and the chronic disabling nature of RA have resulted in a shift to earlier use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). New guidelines released by the American College of Rheumatology in 200218 advocate this switch.27 DMARDs decrease inflammation (confirmed by a reduction in acute-phase reactants), reduce or prevent joint damage, and modify the disease process. The use of DMARDs is now recommended early in the disease course, when joint damage has already occurred or is imminent. Multiple medications fall into this category (Table 160-3). They may be used alone or in combination, but their use may be limited by loss of efficacy or systemic toxicity. Medications are often used in combination, but the decision about which drug to use is often individualized and determined by the clinical severity and loss of function and resultant disability, along with concerns about the safety profile of each given patient.

Systemic glucocorticoids are potent anti-inflammatory agents but have a serious side-effect profile when used in large doses over long periods of time. They are not a good option alone for RA, but are sometimes used in a low dose with other DMARDs. Methotrexate has been used as a very effective DMARD for many years, and is often the standard of care for initial DMARD therapy of RA.28,29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree