Rejuvenation of the Aging Nose

Samuel M. Lam

Edwin F. Williams III

At first glance, a chapter dedicated to rhinoplasty in a book devoted to rejuvenation of the aging face appears misguided. However, the nose undergoes unmistakable signs of aging that should not be ignored by the aesthetic surgeon. Whereas the eye and brow complex draws attention on direct gaze, the neck and chin complex is more acutely noted on lateral view. However, the central position and projection of the nose make it a feature that attracts scrutiny from both the frontal and profile perspectives. The elongated, crooked appearance that the aged nose assumes is particularly remarkable on lateral view and can undermine the surgically rejuvenated appearance of the remainder of the face. The protuberant, irregular proboscis that is the hallmark for rhinophyma may be disfiguring to the individual and, worse yet, may harbor occult carcinoma. With these general aesthetic considerations in mind, the facial plastic surgeon can determine judiciously when rhinoplasty may be warranted for the patient who displays the classic signs of the aging nose.

Besides aesthetic concerns, the aging nose may prove to cripple the patient functionally as well. The inelastic, descended, mature nose exhibits less structural integrity than its younger counterpart and can obstruct nasal airflow substantially. Both the internal and external valves may be compromised by the weakened architecture. Further, the heavy soft-tissue envelope of the rhinophymatous nose may add considerable weight to the nose to compress both nasal valves further. The male patient often suffers from the ravages of nasal aging more so than the female because of the heavier, less angulated attitude that characterizes even the younger masculine nose. Also, rhinophyma appears to be a disease that afflicts the male patient almost exclusively. Therefore, the mature male patient may present more frequently to the physician for corrective surgery than the female because of these preponderant functional concerns. Along with ameliorating the functional deficits of the ptotic, unsupported nose, the surgeon, per force, concurrently addresses some, or most, of the aesthetic attributes. Therefore, the aesthetic and functional dimensions are often inseparable entities; and this chapter elucidates the surgical role for both conditions.

Although this chapter dwells on the peculiar characteristics that define the aging nose, the authors outline a rhinoplasty treatment strategy that may be more broadly applied to all situations. A ptotic tip is not exclusive to the aging nose, and many aesthetic flaws that mar a mature nose detract from the beauty of a more youthful nose. This proviso applies to the functional deficits that characterize the aging nose as well. The diligent rhinoplasty surgeon should tailor his or her surgical strategy to fit a particular patient’s nose but should approach all noses with a systematic policy. This philosophy that embraces simplicity, flexibility, and planning is further detailed in the forthcoming section.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: PATIENT SELECTION AND RELEVANT ANATOMY

Relevant Anatomy of the Aging Nose

Although the nose plays a central role in facial aesthetics, it remains chiefly a respiratory organ that warms, humidifies, and cleanses the ambient air on inspiration. The primacy of nasal function should not escape the surgeon’s consideration when operating on this vital appendage: The responsibility to maintain nasal patency should inform even strictly aesthetic endeavors. Hence, the anatomy is reviewed in terms of both the external aesthetic attributes and the internal functional underpinnings.1

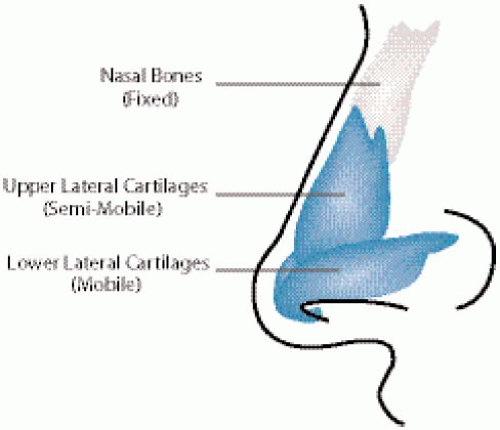

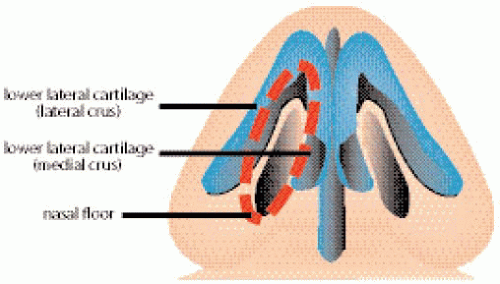

The nose is divided into three constituent elements: the lower flexible third (alar cartilages), middle semiflexible third (upper lateral cartilages), and rigid upper third (the nasal bones) (Fig. 7-1). The flared lower lateral, or alar, cartilages are winged, tapered structures that define the external nares and thereby the external nasal valve. More precisely, the external valve consists of the curved alar cartilage and the nasal floor to complete the circular, valvular ring (Fig. 7-2). The integrity of the external nasal valve is commonly compromised by aggressive rhinoplasty but may be affected by numerous other factors, including congenital weakness, trauma, thermal injury, tumor, and aging. After rhinoplasty, the external valve may collapse either owing to cartilaginous weakening (cephalic resection, domal division,

and various incisions that weaken tip support) or soft-tissue retraction and scarring. Similarly, cartilaginous or soft-tissue weakness predispose toward valvular collapse in the aging nose. During the aging process, the soft tissue loses elasticity and the tissues become attenuated, both of which contribute to the inability to overcome gravitational force and eventual tip ptosis. In addition, the cartilaginous structures of the nose lose some of their tensile strength and the ligamentous structures that bind the cartilages together (scroll, interdomal ligament, etc.) and fasten the cartilage to the surrounding soft tissue (the minor tip-supporting mechanisms) experience some erosion to their strength. The increased sebaceous quality of the nasal tip, known in extreme as rhinophyma, adds weight to the nasal tip and actually may occlude the external naris. All of these factors lead to compromise of the external valve in the aging nose that may require surgical intervention to correct.

and various incisions that weaken tip support) or soft-tissue retraction and scarring. Similarly, cartilaginous or soft-tissue weakness predispose toward valvular collapse in the aging nose. During the aging process, the soft tissue loses elasticity and the tissues become attenuated, both of which contribute to the inability to overcome gravitational force and eventual tip ptosis. In addition, the cartilaginous structures of the nose lose some of their tensile strength and the ligamentous structures that bind the cartilages together (scroll, interdomal ligament, etc.) and fasten the cartilage to the surrounding soft tissue (the minor tip-supporting mechanisms) experience some erosion to their strength. The increased sebaceous quality of the nasal tip, known in extreme as rhinophyma, adds weight to the nasal tip and actually may occlude the external naris. All of these factors lead to compromise of the external valve in the aging nose that may require surgical intervention to correct.

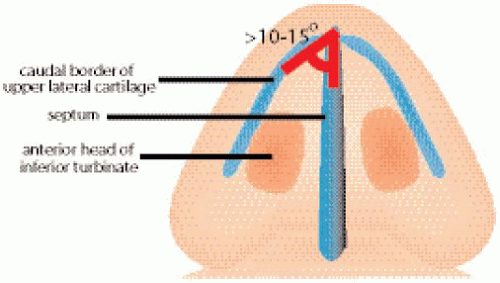

The internal nasal valve, also known as the limen vestibuli, is the major regulator of nasal airflow in the White nose. Mesorrhine and platyrrhine noses that typify the Asian and African noses, respectively, have a much broader crosssection in the region of the internal valve; therefore, they rarely suffer from internal nasal valve collapse. The nasal structures that comprise the internal valve include the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilage, the nasal septum, and the anterior head of the inferior turbinate. The angle formed by the union of the nasal septum and upper lateral cartilages should be a minimum of 10 to 15 degrees in order to ensure patency (Fig. 7-3). A high septal deflection can impinge the upper lateral cartilage and thereby narrow the described angle. The weakening of the cartilaginous support that marks the aging nose can contribute to internal valve collapse. Prior rhinoplasty can detrimentally affect the internal valve (e.g., dorsal reduction severs the upper lateral cartilage-septal union and may predispose toward valvular compromise). A bulbous anterior head of the inferior turbinate, which may arise from allergy, infection, or tumor, or may be a congenital structural anomaly, also can lead to diminished airflow and increased turbulence. All of these structures should be carefully examined during the preoperative consultation (vide infra).

Rhinophyma represents a distinct clinical entity that can cause significant cosmetic and functional disturbance in the aging nose (Case A1). Older men, in particular, are the primary victims of this deforming disease. The comic actor, W.C. Fields, sported perhaps the most notorious example of this elephantine nose. The increased sebaceous activity in the lower third of the nose occurs because of an idiopathic rise in sebaceous gland hypertrophy. Part of the mechanism by which this process may be triggered is attributed to

proliferation of the bacterium, Demodex follicularis. Rhinophyma has been viewed as the end stage of acne rosacea, a dermatologic condition that afflicts the central oilier regions of the face. Topical tetracycline applied regularly during the incipient phase of this disease may control the spread and possibly reverse it. However, once the malady is in full bloom, medical management does little to efface this nowimpregnable entity. Of note, the often-cited belief that rhinophyma originates from alcoholic intemperance is a fallacy that should not be propagated. As mentioned, correction of rhinophyma should address both the aesthetic and functional problems, which include the potential insidious presence of basal cell carcinoma. The most suspicious areas should be sent for pathologic review in the preoperative phase (or intraoperatively at least) if highly suspicious to obtain insurance coverage.

proliferation of the bacterium, Demodex follicularis. Rhinophyma has been viewed as the end stage of acne rosacea, a dermatologic condition that afflicts the central oilier regions of the face. Topical tetracycline applied regularly during the incipient phase of this disease may control the spread and possibly reverse it. However, once the malady is in full bloom, medical management does little to efface this nowimpregnable entity. Of note, the often-cited belief that rhinophyma originates from alcoholic intemperance is a fallacy that should not be propagated. As mentioned, correction of rhinophyma should address both the aesthetic and functional problems, which include the potential insidious presence of basal cell carcinoma. The most suspicious areas should be sent for pathologic review in the preoperative phase (or intraoperatively at least) if highly suspicious to obtain insurance coverage.

A Systematic Approach to Rhinoplasty

Although this chapter is devoted to the surgical management of the aging nose, the reader is encouraged to approach every rhinoplasty in a systematic fashion. This section elucidates the authors’ philosophical approach to all rhinoplasty, which the reader can adapt to fit the circumstance at hand. The three cornerstones that define successful rhinoplasty surgery are simplicity, planning, and flexibility.2 Although these principles appear to be broadly conceived and ill defined, the reader is urged to review this section carefully and contemplate the guiding tenets outlined. After diligent study, the reader will hopefully come to realize the importance that these dictates exemplify.

Simplicity

The guiding principle of simplicity always should be recalled during the preparatory and execution phases of rhinoplasty. Simplicity entails undertaking rhinoplasty with the fewest steps necessary to achieve the aesthetic or functional goals. For instance, a patient who exhibits cephalic fullness to the lower lateral cartilages without notable bifidus should be an eligible candidate for a closed, nondelivery, transcartilaginous technique. The nondelivery technique affords the most expedient and targeted approach to the aesthetic deficit without undue, protracted operative dissection. In contrast, rhinoplasty surgery that entails major architectural destruction followed by extensive structural reconstitution should be condemned if conducted in an indiscriminate fashion. Not every nose justifies aggressive resection: Prolonged surgical manipulation increases variability because of scar contracture over time that may transform a beautiful immediate result into a disaster down the road. The effect of skin “shrink wrapping” over time may reveal any minor flaws in surgical technique or even expose the outline of structural grafts that have been perfectly executed.

Categorically, plastic surgeons are perfectionists by inclination; for that reason, the targeted goal is consistently 100% in every rhinoplasty endeavor. However, if achievement of 100% entails 5 hours of surgery, then the ultimate result may fall far short of the intended mark because of the aforesaid variability that arises from radical surgery. The law of diminishing returns takes hold, because edema distorts anatomy and the hemostatic effects of the local anesthetic dissipate after an hour and a half of operative time.

Instead, the surgeon should think systematically how he or she could arrive at the maximal aesthetic achievement with the minimal of surgical maneuvers. Accordingly, a realistic goal for surgery may be 90% rather than 100%. This is not to concede that 100% is not achievable but rather that it may not be preferable because by doing so the result may approach 80%. These percentages are only presented to help instruct the rhinoplasty surgeon understand the principle of simplicity more precisely and clearly do not represent actual conceived numerical values.

Planning

Planning goes hand in hand with simplicity. In order to achieve the most straightforward, simplest strategy to every rhinoplasty endeavor, proper planning should begin from the first patient encounter. At the conclusion of the initial consultation, the surgeon should outline a plan for surgery that may involve as basic as a few marginal notes jotted down to a more elaborate and complete dictation. Either method of documentation is acceptable so long as the surgeon can readily refer to the proposed plan at the time of surgery and recall what should be done at that later date. With a hectic schedule, it is a wasteful and troubling exercise to begin afresh with surgical planning moments before the actual procedure. Using simplicity as a guide, the surgeon should deliberate seriously whether an external, transcolumellar incision is justifiable. The authors believe that open structure rhinoplasty is a worthwhile venture in select cases but should not be undertaken in every circumstance. The external approach adds increased surgical dissection and operative time that may not be required. Conversely, difficult revision cases may not be suitable to an endonasal approach because of the needs for better visualization and greater structural reconstitution. Letting the punishment fit the crime should dictate how much surgical dissection is necessary. The forthcoming section on operative considerations presents treatment strategies that are based on these guiding tenets of planning and simplicity.

Flexibility

Flexibility constitutes the final consideration that should inform every rhinoplasty effort. Although this principle really refers to intraoperative decision making, it is mentioned in the preoperative section so that the reader can understand

the three guiding tenets of simplicity, planning, and flexibility together. Despite the best efforts at planning an effective strategy, the vicissitudes that may arise during surgery occasionally justify a change in the course of action. This decision to undertake a different surgical tactic defines flexibility. The surgeon should not rigidly adhere to a preconceived plan if that plan begins to appear ill suited to the current situation. For instance, placement of a columellar strut and a transdomal suture may be all that are required to correct a ptotic tip during intraoperative analysis, and the plan for a lateral crural overlay may be justifiably abandoned given the perceived situation. With all three cornerstones in mind, the surgeon should be able to formulate a reliable, systematic strategy for every rhinoplasty and adapt that strategy according to individual constraints. Diligent study of long-term postoperative results confirm or alter future surgical endeavors; and the successful rhinoplasty surgeon should remain a pupil for life.

the three guiding tenets of simplicity, planning, and flexibility together. Despite the best efforts at planning an effective strategy, the vicissitudes that may arise during surgery occasionally justify a change in the course of action. This decision to undertake a different surgical tactic defines flexibility. The surgeon should not rigidly adhere to a preconceived plan if that plan begins to appear ill suited to the current situation. For instance, placement of a columellar strut and a transdomal suture may be all that are required to correct a ptotic tip during intraoperative analysis, and the plan for a lateral crural overlay may be justifiably abandoned given the perceived situation. With all three cornerstones in mind, the surgeon should be able to formulate a reliable, systematic strategy for every rhinoplasty and adapt that strategy according to individual constraints. Diligent study of long-term postoperative results confirm or alter future surgical endeavors; and the successful rhinoplasty surgeon should remain a pupil for life.

Preoperative Evaluation

The three elements of a proper preoperative evaluation include assessment of the psychological motivations and expectations, the history of the patient’s problem, and physical assessment of the aesthetic and functional features of the patient’s nose.

Psychological Evaluation

The psychological inquiry that is mandatory for every cosmetic consultation has been well outlined in Chapter 3. Nevertheless, rhinoplasty often carries with it more psychological overtones than routine, aging-face surgery and deserves special mention herein. Although rhinoplasty of the aging nose is primarily restorative, aesthetic enhancement beyond one’s former, youthful nasal shape may be requested. For example, a mild dorsal hump that is present at youth may become accentuated over time because of nasal tip ptosis. The patient may desire not only correction of nasal ptosis but also removal of the hump altogether. Alternatively, the patient may request aesthetic tip refinement along with improvement of nasal function. As the nose is prominently situated in the center of the face, changing the aesthetic features of the nose may have significant psychological repercussions. Accordingly, the surgeon should decipher the exact aesthetic and functional goals that the patient desires and work to match those objectives after careful investigation of the underlying motivations and expectations.

As mentioned, the male patient often suffers the effects of nasal aging (ptosis or rhinophyma) more acutely than his female counterpart. Unfortunately, men may exhibit a more profound psychological dilemma when electing aesthetic or functional rhinoplasty. Studies have revealed that men are less tolerant of change to their physical facial features. This fact is particularly true for the more mature male patient who already has developed a rather static self-image, as opposed to the more mutable self-perception of the adolescent male.3,4 Although women can adapt easily to their newly shaped visage, men gaze into their reflected image and see an altogether foreign expression. Furthermore, the altered nose proves to be most troublesome aspect of the face for men to accept. Freudian connotations have been made of the nasal appendage mimicking a phallus and surgical correction of which is commensurate with castration. This analogy may strike the reader as grossly absurd; however, significant nasal reduction may be viewed as a form of emasculation, because the strong nasal profile is a hallmark of masculinity. Besides the aesthetic patient, the functional male rhinoplasty patient may prove equally frustrating. The classic, “engineer”-minded individual approaches the physician, often clutching in tow elaborate, self-executed diagrams that attempt to instruct the physician how best to alleviate the nasal impairment. Typically, these illustrations serve to impart little substantive information but only to underscore the fixated frame of mind that the patient is exhibiting. Most often, this type of patient has already journeyed tirelessly to find the elusive surgeon who will address his or her every complaint. The plastic surgeon always should be attentive during the preoperative phase to determine not only which patient should be operated on but more important, which one should not.

Historical Evaluation

A thorough and complete history should be taken to ascertain the patient’s aesthetic and functional concerns. The details of good history taking already should be well understood by the physician. Nevertheless, a few salient points that are particular to rhinoplasty are mentioned here. The psychological motivation for aesthetic improvement has been addressed in the previous section. Apart from psychological issues, the surgeon must endeavor to determine exactly what aesthetic flaws concern the patient. The consultation process should reflect the progressive union of the patient’s desires with the educated opinion of the surgeon. Aesthetic goals that may compromise nasal function should be tempered appropriately. For instance, overly narrowing the nose may not be achievable given poor elasticity or already impaired nasal airflow. A crooked nose is a very difficult entity to correct fully, and the surgeon should declare the limitations of surgical intervention to establish realistic expectations. History that should be elucidated includes prior trauma, nasal and sinus surgery (both aesthetic and functional), allergy and sinus disease, and other related systemic illnesses. The precise nature and extent of prior surgery should be delineated so that planning for the current endeavor can be maximized. Previous operative dictation can be helpful but often is misleading or vague. Therefore, an in-depth history and attentive physical examination may serve as a next best proxy for this lack of knowledge.

For functional complaints, the surgeon should probe the exact circumstances when the nasal impairment occurs or is exacerbated. If the nasal obstruction arises only temporarily, then surgical intervention may not be justified and medical therapy may be warranted instead. If allergy or other medical conditions can be ruled out, then precise localization of the nasal impairment often is uncovered during the physical examination.

Physical Examination

Nasal aesthetic and functional flaws may be most clearly ascertained with a thorough physical examination. Most of the physical examination may be completed during the initial portion of the consultation in which the patient reports the aesthetic problems that trouble him or her. Therefore, the physical examination may be integrated into the dialog with the patient and any remaining aspects of the examination that were not formally covered early on are evaluated at this point. First, the nose is inspected for symmetry and compliance with aesthetic guidelines.

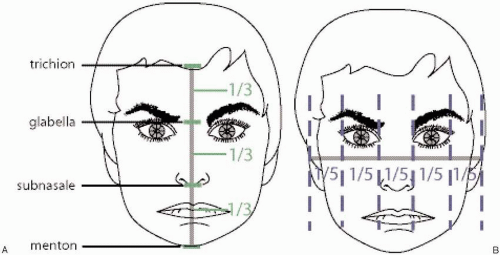

Ideal nasal and facial aesthetic proportions have been reported widely. However, a brief review is included herein. The nasal length (from glabella to nasal tip) should occupy approximately one third of the total vertical height of the face. The upper one third of the face should extend from the hairline to the glabella, and the lower one third should cover the distance from the bottom of the nose to the lower aspect of the chin, or menton (Fig. 7-4A). As the patient matures, the nose elongates because of gravity and loss of elasticity so the nose comes to occupy more than one third of the vertical facial height. Similarly, the lower third of the face shortens because of the encroachment of the longer nose over the upper lip. As the male patient matures, the loss of frontal hair translates into a longer upper one third of the face. However, as the chapter on hair restoration details, the upper third of the face should not be shortened to the golden one-third distance to avoid a prepubescent appearance of the hairline. Horizontally, the nasal width should equal that of an eye, forming one fifth of the total distance across the face. The distance from the lateral canthus to the lateral aspect of the flared ear should occupy the remaining one fifth of the face (Fig. 7-4B). Aging does little to impact on the proportion of the horizontally divided face.

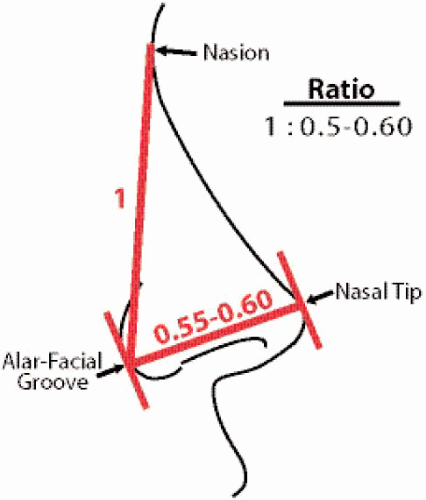

On profile view, nasal projection has been defined by many formulae. A simple method that has proved clinically reliable is the one described by Goode: The distance from the alar-facial groove to the nasal tip should equal to 0.55 to 0.60 of the distance from the nasion to the alar-facial groove (Fig. 7-5). Generally speaking, the male nose can tolerate a

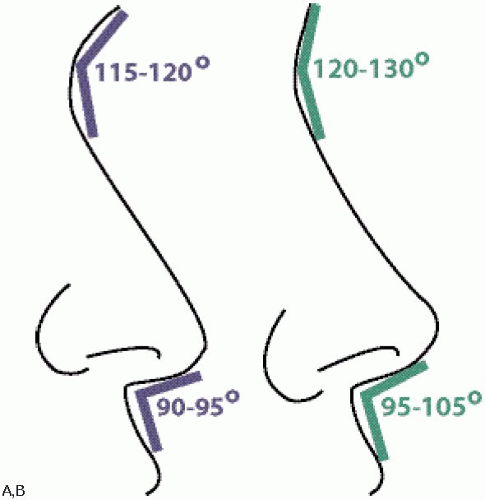

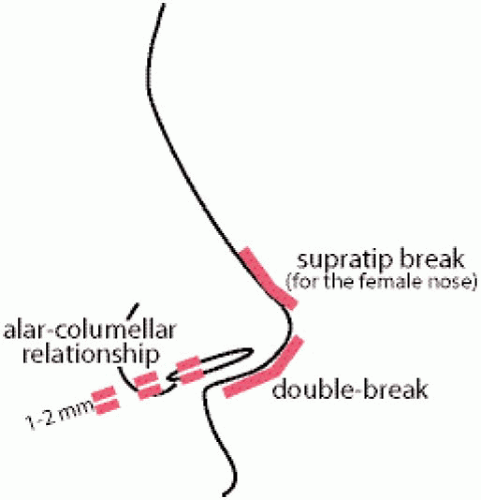

greater degree of projection than that of the female nose. The rotation of the nose defined by the columellar-labial angle should be more perpendicular for the male, approximately at 90 to 95 degrees, whereas the ideal female rotation rests between 95 to 105 degrees (Fig. 7-6A,B). As the patient matures, this angle becomes more acute, and restorative surgery should aim to return the nose to the ideal attitude. The nasofrontal angle is narrower for the male, ranging ideally between 115 to 120 degrees owing to the heavier male brow and is more open for the female, situated between 120 to 130 degrees (Fig. 7-6A,B). On profile, the male nose can tolerate a slight dorsal convexity, or hump, whereas the female nose should be relatively straight in contour. A slight supratip break, or depression, is a favorable aesthetic attribute for the female but is not so for the male. A double-break contour of the columella-lobule region is a natural and pleasing configuration that should be maintained or improved with surgery. Finally, the alar-columellar relationship should be such that a perfect oval shape of the nostril is viewed laterally with the distance from the ala to the columella approximating 1 to 2 mm (Fig. 7-7). An entire book can be dedicated to the description of ideal aesthetic values, but this brief review should serve as a basic framework with which the rhinoplasty surgeon can assess the patient’s nasal features.

greater degree of projection than that of the female nose. The rotation of the nose defined by the columellar-labial angle should be more perpendicular for the male, approximately at 90 to 95 degrees, whereas the ideal female rotation rests between 95 to 105 degrees (Fig. 7-6A,B). As the patient matures, this angle becomes more acute, and restorative surgery should aim to return the nose to the ideal attitude. The nasofrontal angle is narrower for the male, ranging ideally between 115 to 120 degrees owing to the heavier male brow and is more open for the female, situated between 120 to 130 degrees (Fig. 7-6A,B). On profile, the male nose can tolerate a slight dorsal convexity, or hump, whereas the female nose should be relatively straight in contour. A slight supratip break, or depression, is a favorable aesthetic attribute for the female but is not so for the male. A double-break contour of the columella-lobule region is a natural and pleasing configuration that should be maintained or improved with surgery. Finally, the alar-columellar relationship should be such that a perfect oval shape of the nostril is viewed laterally with the distance from the ala to the columella approximating 1 to 2 mm (Fig. 7-7). An entire book can be dedicated to the description of ideal aesthetic values, but this brief review should serve as a basic framework with which the rhinoplasty surgeon can assess the patient’s nasal features.

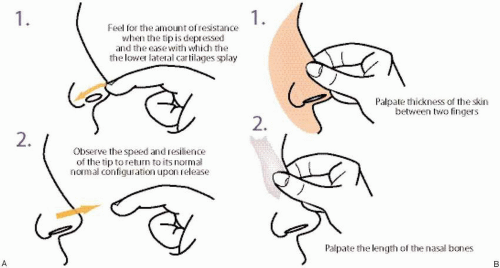

After the nasal anatomy has been studied visually, the surgeon should evaluate the nasal soft tissues by palpation. The nasal tip should be depressed with a finger and released to determine tip recoil (Fig. 7-8A). If the lower lateral cartilages splay easily under pressure and do not spring back to their normal configuration after release, then surgery should be tailored to reflect the weaker condition of the cartilages. For instance, significant trimming of the lower lateral cartilages should be avoided in these circumstances. The skin thickness also should be appreciated, because thin skin may expose any surgical imperfections over time and thick skin may camouflage the surgical result (Fig. 7-8B). Therefore, medium-thick skin is ideal for rhinoplasty. The length of the nasal bones should be palpated because short bones predispose toward an inverted-V deformity. This complication appears as a cutaneous, inverted-V depression between the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages, because the middle vault collapses owing to lack of bony support after surgical manipulation. In these cases, osteotomies may need to be avoided or spreader grafts placed to buttress the upper lateral cartilages (the middle vault) against inward collapse. Any bony irregularities also should be studiously palpated and recorded.

After all of these external landmarks and structures have been adequately assessed, the surgeon should then turn his or her attention to the internal aspect of the nose. If the patient reports nasal obstruction, the surgeon should begin the nasal examination by observing the patency of the external nasal valve. Without touching the patient’s nose or inserting a nasal speculum, the surgeon observes the nares in repose and in dynamic contraction during quiet respiration. At rest, the external valve already may appear to be compromised by virtue of a narrowed nostril aperture. Alternatively, the external valve may appear to collapse only with inspiration owing to weak lateral alar support. If either condition is noted, then a cotton-tipped applicator can be used to stent the nostril open to determine if this action alleviates the nasal obstruction. A finger that is positioned just lateral to the ala on the cheek skin can be used to distract the cheek laterally and thereby open the nostril. If these techniques improve symptomatic nasal airflow, then external nasal valve collapse is present. For the aging nose, the external valve may be reduced by nasal tip ptosis. Therefore, lifting the nasal tip back to a more upright position may eliminate nasal congestion that corroborates external valvular compromise. The following section describes methods to address external valvular problems.

Next, the internal nasal cavity should be inspected for signs of septal, turbinate, or internal valvular compromise. A nasal speculum can be placed to widen the nasal aperture for better visualization of the internal anatomy, and a headlight provides proper illumination. The septum should be checked for deviation, and a comparative view of both nasal cavities may render a more accurate assessment as to the presence of a septal deflection. A high septal deflection located

at the junction of the upper lateral cartilage and septum should be carefully studied, because this narrowed passage may be related to internal valve restriction. As mentioned, the anterior head of the inferior turbinate is also a constituent element of the internal nasal valve, and enlargement of this tissue may restrict nasal airflow. Erythematous, purulent turbinates suggest a bacterial etiology for the inflammation, whereas pale to violaceous and edematous mucosa may indicate an allergic source. After anterior rhinoscopy has been concluded, the nasal speculum should be removed. Then, if internal valve collapse is entertained, a cotton-tipped applicator should be gently inserted into the nose to stent the upper lateral cartilage away from the septum. The applicator tip should be applied against the upper lateral cartilage near the septal-upper lateral cartilage junction (Fig. 7-9A). If the patient is equivocal about the improvement, then the contralateral side should be tested in a similar fashion to offer the patient a comparative perspective. Finally, the cheek should be distracted immediately lateral to the upper lateral cartilage very gently to determine if there is any improvement with this technique (Cottle maneuver) (Fig. 7-9B). This method carries value only if the finger distracts the upper lateral cartilage (at the internal nasal valve) and not the nostril (i.e., the external nasal valve.) Similarly, the external valve can be stented open with a cotton-tipped applicator, nasal speculum, or finger distraction against the cheek. The following section on surgical technique elaborates on correction of internal valvular collapse.

at the junction of the upper lateral cartilage and septum should be carefully studied, because this narrowed passage may be related to internal valve restriction. As mentioned, the anterior head of the inferior turbinate is also a constituent element of the internal nasal valve, and enlargement of this tissue may restrict nasal airflow. Erythematous, purulent turbinates suggest a bacterial etiology for the inflammation, whereas pale to violaceous and edematous mucosa may indicate an allergic source. After anterior rhinoscopy has been concluded, the nasal speculum should be removed. Then, if internal valve collapse is entertained, a cotton-tipped applicator should be gently inserted into the nose to stent the upper lateral cartilage away from the septum. The applicator tip should be applied against the upper lateral cartilage near the septal-upper lateral cartilage junction (Fig. 7-9A). If the patient is equivocal about the improvement, then the contralateral side should be tested in a similar fashion to offer the patient a comparative perspective. Finally, the cheek should be distracted immediately lateral to the upper lateral cartilage very gently to determine if there is any improvement with this technique (Cottle maneuver) (Fig. 7-9B). This method carries value only if the finger distracts the upper lateral cartilage (at the internal nasal valve) and not the nostril (i.e., the external nasal valve.) Similarly, the external valve can be stented open with a cotton-tipped applicator, nasal speculum, or finger distraction against the cheek. The following section on surgical technique elaborates on correction of internal valvular collapse.

INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: TECHNIQUE AND SALIENT TECHNICAL POINTS

Aesthetic and Functional Rhinoplasty of the Aging Nose

General Remarks

Rhinoplasty is a vast and complicated subject that would require several volumes of writing to do it justice. Although the previous section outlined a general approach to rhinoplasty, this section on intraoperative management only details the surgical maneuvers relevant to correction of the aging nose (both functional and aesthetic). The preoperative section presented broader themes in order provide the reader with a framework with which to approach rhinoplasty according to the authors’ philosophy. This section remains true to the objective of this book (i.e., surgery for facial rejuvenation). If the reader requires more in-depth knowledge about rhinoplasty, he or she is referred to Eugene Tardy’s masterpiece, Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science,5 or Jack Sheen’s illustrious text, Aesthetic Rhinoplasty,6 for

greater detail. Interestingly, even texts that are dedicated to rhinoplasty often fail to include a chapter that specifically outlines a treatment strategy for the aging nose. Certainly, rhinophyma resection is considered too outré for inclusion within the subject of most rhinoplasty textbooks. This chapter hopefully adds a rational treatment strategy for the aging nose to the existing body of literature.

greater detail. Interestingly, even texts that are dedicated to rhinoplasty often fail to include a chapter that specifically outlines a treatment strategy for the aging nose. Certainly, rhinophyma resection is considered too outré for inclusion within the subject of most rhinoplasty textbooks. This chapter hopefully adds a rational treatment strategy for the aging nose to the existing body of literature.

Instrumentation and Equipment

Instrumentation/Equipment for Rhinoplasty

Prep Stand:

Nonsterile gloves

10-cc syringe, 27-gauge (1¼ inch long) needle with 1% lidocaine and 1:50,000 epinephrine

Bowl with four long nasal pledgets soaked in equal parts of oxymetazoline and Pontocaine

Nasal speculum

Bayonet forceps

Surgical marking pen

Instruments:

Nasal tray that includes:

Takahashi forceps

Large Rubin elevators

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree