Hair Restoration

Samuel M. Lam

Edwin F. Williams III

Cosmetic surgery for men has dramatically increased in popularity over the past decade, spurred in part by mass media images that portray the idealized male form. Aesthetic surgery is a natural extension of the fitness fixation that has captivated the male ego and propelled it on a quixotic quest in pursuit of the Adonis physique. Although many men seek global rejuvenation of the face, societal norms dictate two principal facial regions that receive disproportionate attention: the eyes and the hair. Blepharoplasty offers the male patient who thrives in the competitive workplace a targeted approach toward rejuvenation: Aging eyes often betray fatigue, anger, and sadness that may belie the patient’s true emotional state or youthful vigor. Similarly, hair restoration has become a principal concern for the mature, or not quite so mature, man who faces the tragic loss of hair. The ubiquitous media engine often portrays the balding man as a Samson, who stripped of his virile lock, has lost his sexual vitality. Unfortunately, the counterfeit claims of miracle cures that abound on the Internet, on television, and in print do little to provide any meaningful remedy to the bewildered man. Undoubtedly, men fall prey to hormonally incited hair loss to a greater frequency and extent than the opposite sex. Nevertheless, women are susceptible to hair loss, whether androgen-driven or otherwise, and they have sought medical and surgical therapy for their condition as well.

The history of follicular transfer dates back two centuries to Dieffenbach’s early experiments.1 It was not until Orentreich introduced his elegant punch-grafting technique in the 1950s that follicular grafting was more precisely understood and widely implemented.2 Nevertheless, the original punch graft left an indelible image in the public mind that has been likened to the cornrow appearance of a doll’s head. These unsightly “plugs” hindered widespread acceptance of this technique. In the early 1980s, Nordstrom and Marritt pioneered the use of micrografting, or single follicular transfer, that offered a more natural appearance to the grafted scalp.3,4 Alternatively, scalp reduction with extender placement (see the following) has been useful to correct crown, or vertex,* baldness, because grafting in this area may appear unnatural. Scalp rotation flaps (e.g., the twice-delayed Juri flap) are beneficial for patients who desire rapid, dense coverage to the fronto-temporal region.5,6 Tissue expansion has also been successfully implemented for hair restoration but has not been exploited in the authors’ practices (and accordingly is not discussed herein.) Beyond these varied surgical options, advances in medical treatment have provided sufferers of alopecia a less invasive alternative. The physician who treats alopecia should be acquainted with the diverse treatment methodologies to combat follicular loss and exercise erudition in the selection of the appropriate course of action. This chapter reviews the many surgical and medical treatment strategies that currently exist for hair loss and emphasize a systematic appraisal to guide therapy.

The surgeon whose primary talent is brandishing the scalpel may find the multifaceted approach to hair restoration a daunting ordeal. Accordingly, many disciplines may need to converge, including a medical therapist or physician, an operative technician, and a hairpiece specialist, to provide the balding patient the optimal care that he deserves. Often, a patient may not be ready to undertake surgical hair restoration because of financial constraints, fear, lack of motivation, or insufficient hair loss to justify transplantation. These patients may be better candidates for medical therapy (e.g., minoxidil or finasteride) until surgery becomes a more suitable option. Herbal remedies, albeit often clinically unsubstantiated, may offer an unconventional, yet perhaps beneficial, regimen for alopecia. A physician or a therapist may play a valuable role in dispensing medical or herbal treatments, respectively. Alternatively, the same or another provider can tender services that rely on hairpiece camouflage. Clearly, the field of hair restoration is broad and complex and may require a team working independently or together to achieve the aesthetic objectives of the patient.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: PATIENT SELECTION AND RELEVANT ANATOMY

The first step toward successful surgical hair restoration is proper physician-patient dialog to establish the desire, motivation, and expectation that the patient harbors. Despite what may be glaringly obvious to the transplant surgeon as the most deficient area of alopecia, the patient may hold an altogether different opinion of what troubles him or her. The consultation should aim at unifying patient concerns with the surgeon’s objectives in a realistic, achievable fashion. Despite the most talented and extensive grafting efforts, some patients who desire significant density may be left unsatisfied with conventional graft transplantation. Conversely, a patient who expresses trepidation about extensive surgery may not be a suitable candidate for scalp rotation and reduction procedures. Besides the psychological aspects of hair transplantation, the anatomic constraints of a patient’s particular hair, scalp, and donor areas should be entered into the equation when selecting the appropriate surgical approach. The following section highlights the salient points regarding proper patient selection given the previously enumerated limitations.7

First, a thoughtful and thorough history always should be obtained about a patient’s onset, rapidity, and evolution of hair loss. As will be discerned, a mature, stable hairline affords the surgeon a wider range of surgical options than a rapidly progressive hairline of a younger patient. Nevertheless, an apparently very stable hairline may become less so because of both intrinsic or extrinsic factors at any time; and the surgeon should never hold an unwavering conviction that the past is an absolute predictor of the future. Prior medical history that may contribute to the development of alopecia also should be elucidated, including radiation exposure, medication abuse, hormonal imbalances, dietary deficiencies, or other inciting factors. A history of prior medical therapy using approved (finasteride and minoxidil), herbal (saw palmetto and vitamins), experimental (dutasteride), and other medicinal or quasimedicinal compounds should be elicited. The duration of medical therapy may hint at the length of time that the patient has been troubled by his or her hair loss, and to what extremes he or she has pursued various avenues to ameliorate the condition. Prior surgical efforts also should be properly assessed, as well as the patient’s satisfaction or displeasure with those interventions.

A focused physical examination should follow of the scalp and hair. Hair color, texture, density, curliness, and distribution should be evaluated along with scalp color, elasticity, and integrity. These attributes determine the overall success of the transplantation, as succeeding portions of this chapter more readily reveal. For instance, dark, thick, straight hair contrasted against a milky white scalp may be the least forgiving combination and may yield a less natural look despite best efforts at follicular unit or micrografting, especially in the region of the vertex. Donor density also must be evaluated: A thick occipital fringe provides ample donor source for grafting transplantation, whereas a robust parietal fringe may contribute more to the success of a scalp flap rotation or reduction. The fronto-temporal recession should be attentively studied, as surgical blunting or effacement of these “character lines” often leads to an unnatural look and may make further camouflage in a rapidly receding hairline difficult. Obviously, the surgeon must plan his or her procedure to provide both immediate benefit but also aim at overall longevity: These twin goals always should be kept in mind.

As alluded to, the psychological dynamics that motivate the patient are central to success of any hair transplantation. The patient’s expectations of the transplantation session must be met to ensure surgical triumph. First, the patients’ desire for density versus coverage should be determined. Some patients, especially those who have been accustomed to synthetic hairpieces, may not perceive simple coverage in the areas of alopecia to be sufficient and may insist on greater density than can be afforded by grafting sessions. If the photographic results of patients who have undergone “megasession” grafting sessions are nevertheless uninspiring, then scalp rotation and reduction may be entertained to resolve this perceived inadequacy. However, most men are quite satisfied with any coverage they may achieve; therefore, they are usually excellent candidates for transplantation.

In contradistinction, the authors have noted that women, who naturally tend to exhibit less widespread hair loss, often remain discontented with their surgical result despite very extensive transplantation. Unlike discrete areas of androgenic alopecia that preside in the fronto-temporal and crown regions, female-pattern baldness is more evenly distributed across the scalp and less extensive in nature. Accordingly, women tend to be less satisfied with follicular grafting because the amount of hair loss is less perceptible to begin with and surgical enhancement of more dispersed alopecia may be similarly less noticeable. The generalized thinning that occurs in the female sufferer of alopecia has been classified according to the Ludwig scale8 (Fig. 6-1) as opposed to the Norwood scale for men (Fig. 6-2). As part of an informed preoperative consultation, the surgeon must ensure that the limitations of surgical hair restoration for the female patient are well understood before surgery is contemplated.

Similarly, patients who desire significant density also may express impatience with the 6 months to 1 year required to see the incipient regrowth of the newly transplanted hair. In addition, several transplantation sessions that are necessary to achieve considerable density may further delay noticeable growth and add overall expense if the cumulative number of grafting sessions is tallied. For the minority of patients who are unwilling to wait and who desire rapid, dense growth of hair, a scalp rotation or reduction

may be the optimal surgical approach for them. All these concerns again must be tempered with the added morbidity of staged flap or reduction procedures that may contribute to an undesirable convalescence.

may be the optimal surgical approach for them. All these concerns again must be tempered with the added morbidity of staged flap or reduction procedures that may contribute to an undesirable convalescence.

Patients who may be good candidates for scalp reduction techniques are those who suffer from exclusive crown, or vertex, alopecia and who are of a mature age (more than 40 years old), with stable hair recession. Patients who continue to lose significant hair may expose their suture line and require further sessions of scalp reduction in an already tight and incompletely distensible scalp. In addition, patients should be counseled preoperatively on the likely further loss of some hair near the incision line. As mentioned, preoperative scalp elasticity should be assessed before consideration of scalp reduction. Curiously, scalp distensibility is less of a concern if an extender is used as part of the procedure, because the implanted device tends to overcome some of the unfavorable tensile forces of the inelastic scalp.

Scalp reduction is really only possible as a serious alternative to follicular grafting as a result of Patrick Frechet’s brilliant invention, the scalp extender, in 1993.9 The technique of scalp reduction was first introduced in 1977 by the Blanchards,10 but has undergone a variable course of success because of two complications: stretchback11 and slot deformity. Prior to the implementation of an extender, the reduced bald scalp stretches back partially: the surgical equivalent of taking two steps forward and one step back (Fig. 6-3). The Frechet extender consists of a central extensible silastic sheet with titanium hooks attached on both ends: The device is implanted below the reduced scalp so that no stretchback occurs in the reduced bald area (unfavorable stretchback) but only takes place in the hair-bearing periphery (favorable stretchback). Slot deformity refers to the remaining slot-shaped bald area that persists along the incision line after all the scalp-reduction sessions have been completed. The authors have relied on a multiple z-plasty closure to camouflage this potential deformity and occasionally follicular grafting to disguise the defect further if necessary during the last session.

Scalp reduction has proved a reliable method in the authors’ hands for select patients with crown baldness. On the other hand, successful follicular grafting of the exposed crown may yield at times a less favorable result. Generally speaking, the crown area may be the most difficult to address because of the so-called “bleacher-stand effect” (i.e., grafts seen from behind and above the patient may appear “pluggy” in appearance). However, if the patient demonstrates a favorable combination of dark-complexioned skin and light-colored hair then follicular grafting to the vertex may be much more forgiving and yield a natural appearance. Intense follicular grafting along follicular unit divisions is the preferred method to graft the exposed crown in order to maximize the likelihood for a natural result. Interestingly, the most labor intensive grafting sessions in the vertex may still be unrewarding, as patients often fail to appreciate an area that is not directly in their daily view unlike the comparatively more ecstatic reviews received for the transplanted fronto-temporal region.

As briefly mentioned, the younger patient (less than 40 years old) or the patient with unstable and rapidly progressive hair loss may not be a suitable candidate for scalp reduction. After closure of the exposed crown, this type of patient may continue to lose significant hair and make incision-line camouflage challenging. Flap design principally involves recruitment of parietal hair into the central defect. Accordingly, donor hair in the parietal fringe should be sufficiently thick to provide density to the exposed crown and to tolerate some degree of stretchback in the donor area. The occipital-fringe donor site is also recruited for closure but tends to be less distensible in tissue advancement owing to the adherence of the occipitalis musculature to the posterior nuchal line.

The patient who desires rapid, dense coverage of the fronto-temporal region and who possesses adequate parietal donor hair may be eligible for scalp rotation with the Juridesigned, twice-delayed, temporo-parietal-occipital flap. In the authors’ experience, even patients who have undergone multiple, extensive transplantation sessions are exulted by the unparalleled density that they receive from a single flap rotation procedure. If needed, the contralateral parietal bed may be recruited as a second Juri flap to add density behind the first flap. Unlike scalp reduction, which mandates a more stable pattern of hair recession, fronto-temporal coverage with a flap rotation does not demand this prerequisite. Nevertheless, rapid, ongoing hair loss of the fronto-temporal region may make a scalp rotation less than desirable, because

future follicular grafting sessions are required to camouflage the exposed posterior aspect of the flap. However, a detailed history should also delve into tobacco usage that may unnecessarily jeopardize flap viability. The authors elect to abstain from undertaking any flap procedure in an individual who is actively smoking. Complete cessation of this habit must be ensured 2 weeks before the initial flap elevation and maintained for the duration of all three phases of the procedure; and record of patient compliance must be documented in the medical chart. Once more, it should be emphasized that most patients are more psychologically disposed to hair grafting transplantation, and this technique serves as the primary means by which to address androgenic alopecia and has provided very satisfying results for surgeon and recipient alike.

future follicular grafting sessions are required to camouflage the exposed posterior aspect of the flap. However, a detailed history should also delve into tobacco usage that may unnecessarily jeopardize flap viability. The authors elect to abstain from undertaking any flap procedure in an individual who is actively smoking. Complete cessation of this habit must be ensured 2 weeks before the initial flap elevation and maintained for the duration of all three phases of the procedure; and record of patient compliance must be documented in the medical chart. Once more, it should be emphasized that most patients are more psychologically disposed to hair grafting transplantation, and this technique serves as the primary means by which to address androgenic alopecia and has provided very satisfying results for surgeon and recipient alike.

Evaluation of the Surgical Candidate

Psychology

What area troubles the patient? (fronto-temporal versus crown)

What are the patient’s expectations? (natural hairline, dense coverage)

How long has the patient been concerned about the hair loss and what steps has he or she taken to ameliorate the condition? (hairpieces, sprays, medications, surgery)

History

What are the onset, rapidity, and pattern of hair loss?

What is the patient’s general overall health? (diabetes, immunosuppression)

What medications has the patient tried to correct hair loss (including prescribed, herbal, experimental medications)?

Has the patient undergone any surgery or trauma to the scalp or hair?

Has the patient been exposed to any radiation insult to the hair-bearing region?

Any related autoimmune diseases?

Does the patient smoke or use any form of tobacco?

Any illicit drug history?

Physical

Hair color, texture, curliness (lighter, thinner, curlier hair is preferred for a natural, less “pluggy” hair transplantation)

Scalp color and elasticity (darker color is preferred for a natural, less “pluggy” hair transplantation)

Donor site: the density, extent, nature, and location of the hair

Recipient site: determine the extent of the area that the patient desires for transplantation

Selection of Surgical Technique

Follicular Grafting

Fronto-temporal region is area of primary concern

Good occipital or temporal donor sites

Scalp Reduction

Crown, or vertex, is area of primary concern

Dark hair and light skin make follicular transfer in crown region more noticeable (the bleacher-stand effect).

Therefore, scalp reduction may be preferred.

The area of exposed crown does not exceed 12 cm.

Good scalp distensibility

No significantly progressive hair loss in the crown area

Scalp Rotation

The fronto-temporal region is area of primary concern.

The patient is accustomed to the density provided by a synthetic hairpiece.

The patient desires rapid, dense coverage of the fronto-temporal region.

Good temporo-parietal-occipital donor site(s)

Nonsmoker

Instrumentation and Equipment

Instrumentation/Equipment for Follicular Grafting

Prep/Surgical Stand:**

Nonsterile gloves

Surgical marking pen

Electric razor

Wide paper tape to hold hair away from donor site

Hair comb

10-cc syringe (4), 18-gauge needle with 0.9% normal saline

10-cc syringe (4), 27-gauge needle with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Needle holder

Tori triple-blade handle outfitted with three No. 10 blades

18-gauge NoKor needle (Becton Dickinson & Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) or SP90 (Micro spear point) blade for graft insertion

Jeweler’s forceps (2)

Babcock (or tenaculum)

Adson-Brown forceps

Hand drill with 1.75-mm hollow drill bit (Robbins Instruments, Inc., Chatham, NJ)

2-0 polypropylene C-3 (N/A, CE-2) [C17]† for donor site closure

Graft Dissection/Preparation Table:

Powder-free gloves (sterile)

Petri dishes (4)

Single-edged razor blades

Magnification visors (loupes or dissecting microscopes)

Small bowls with normal saline (2), to wash the grafts

Disposable Plexiglas platforms, for graft dissection

Illumination view boxes, on which to dissect the grafts

Adson-Brown forceps (2), to separate the strip grafts

Jeweler’s forceps (4), for individual graft dissection

Spray bottle with sterile water or normal saline

Instrumentation/Equipment for Scalp Reduction

Prep Stand:

Nonsterile gloves

Surgical marking pen

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge needle with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Surgical Table:

Bard-Parker No. 10 blade

Two heavy clamps

Wide-double hooks

Large needle holder

Adson-Brown forceps

LaRoe undermining forceps (9¾″ and 12¾″, Robbins Instruments, Inc.)

Frechet-style Scalp Extender‡

2-0 polypropylene C-3 (N/A, CE-2) [C17] for wound closure

Instrumentation/Equipment for Scalp Rotation

First Stage:

Nonsterile gloves

Surgical marking pen

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge needle with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Doppler probe and instrumentation

Surgical lubricant for Doppler probe

Basic soft-tissue instrument set (Chapter 4)

Bipolar cautery

Skin stapler

Second Stage:

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge needle with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Basic soft-tissue instrument set (Chapter 4)

Bipolar cautery

Skin stapler

Third Stage:

Nonsterile gloves

Surgical marking pen

10-cc syringe (2), 27-gauge needle with lidocaine 1% and 1:100,000 epinephrine

Doppler probe and Instrumentation (optional to confirm patency of vascular pedicle)

Surgical lubricant for Doppler probe

Basic soft-tissue instrument set (Chapter 4)

Bipolar cautery

Monopolar cautery

Skin stapler

6-0 polypropylene suture, P-3 (P-13, PRE-2) <RE-3> needle

3-0 polypropylene suture, PS-2 (P-12, PRE-4) <RE-2> needle (Instead of 3-0 polypropylene, 4-0 polypropylene suture, with a FS-2 (C-13, CE-4) <KTE-6> needle can be used.)

Jackson-Pratt closed suction drain

INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS: TECHNIQUE AND SALIENT TECHNICAL POINTS

Although scalp reduction and rotation methods have been used with success in the treatment of alopecia, follicular grafting remains the mainstay of therapy for surgical hair restoration. In the authors’ practices, follicular grafting accounts for over 95% of surgical hair restoration; and this technique is the only acceptable method for female-pattern baldness. Over the past decade, the senior author has evolved his technique from minigrafting and micrografting now to incorporate follicular unit grafting as well. These terms are clarified before embarking on the surgical narrative. Other modifications have been made in grafting techniques that stress maximal density, a preeminent concern for the patient with alopecia. The technique outlined herein represents state-of-the-art follicular transfer as the senior author practices today, and the clinical case studies at the end of this chapter reveal some of the important changes that have been implemented over this past decade.

In order to obtain a firm grasp on the particular technique that is advocated in this section, the reader should understand some fundamental terminology only briefly alluded to in the foregoing text. The two principal schools of follicular grafting fall under the rubrics: “follicular unit grafting” and “minigrafting and micrografting.” Follicular unit grafting has been a popular method of hair restoration over the past decade.12 Hair follicles are not evenly distributed across the scalp but grow in discrete clusters of one to four hairs, so-called “follicular units” (Fig. 6-4). Many hair restoration surgeons promote dissection of all follicular grafts along these follicular units in order to achieve the most natural appearance (Fig. 6-5). However, transfer of an entire bald scalp with this technique can be a tedious affair. The terms micrografting (one- to two-hair grafts) and minigrafting (three- to six-hair grafts) represent an alternative method to partition grafts. These terms only describe the number of hairs per single graft, irrespective of how these hairs grow in follicular units. However, during graft dissection, the easiest method to cleave individual grafts is typically along follicular unit divisions. Larger minigrafts that carry five- to six-hair grafts represent more hairs than grow in a follicular unit but may consist instead of two neighboring follicular units. Some surgeons advocate placement of micrografts along the anterior hairline to achieve a natural appearance and then insertion of minigrafts more posteriorly to achieve rapid density in this region. The senior author

relied principally on this technique for many years. Currently, a combination of follicular unit transfer and minigrafting and micrografting is used to achieve a more natural result and optimal density, as explained in the following.

relied principally on this technique for many years. Currently, a combination of follicular unit transfer and minigrafting and micrografting is used to achieve a more natural result and optimal density, as explained in the following.

FIGURE 6-5. Close up of four individual follicular unit grafts with (from left to right) one, two, three, and four hairs per graft. |

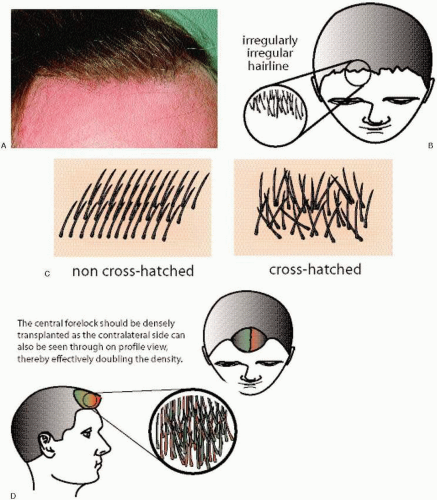

Some of the principles described here are repeated again in detail later in this section but are presented at this point simply as an overview. The anterior hairline may constitute the most important region to address, because the patient and onlookers scrutinize this area most often owing to its high visibility on direct gaze. The remaining scalp posterior to the anterior hairline is relatively camouflaged when viewing the patient directly. Accordingly, the principal concerns when approaching the anterior hairline are creation of a natural appearance and attainment of maximal density. In order to achieve these goals, the senior author relies heavily on densely packed follicular unit grafts along the anterior hairline. To obtain a natural appearance, the finer, vellus hairs located more inferiorly in the posterior occiput are used in the anterior-most rows, and the rows are graduated from one-hair grafts to one- to two-hair grafts to two- to three-hair grafts, with each successive row moving anterior to posterior. In addition, the anterior hairline is designed in an irregularly asymmetrical pattern rather than a straight-line configuration (Fig. 6-6A,B). To gain maximal density, the hairs are placed at different angles to one another, or “crosshatched,” to obscure the naked scalp below (Fig. 6-6C). The central forelock also is more heavily addressed because this area can be viewed from both the left and right sides of the patient; therefore, the grafts are effectively doubled visually in this area (Fig. 6-6D). These concepts are further elaborated later in this section. Creation of the anterior hairline represents the most labor-intensive aspect of follicular grafting but deserves this attention for the stated reasons. The more posteriorly situated scalp extending to the midscalp and crown demand primarily density, which can be more easily achieved with larger “minigrafts” that fall in the fiveto six-hairs-per-graft size. A 1.75-mm diameter, roundpunch device is used to create the recipient sites for these larger 2-mm grafts. Judicious combination of follicular unit and minigrafting and micrografting techniques permits the most rapid but natural restoration of hair than either technique alone.

Hairline Design

Prior to administration of anesthesia, the surgeon should review with the patient exactly which areas of alopecia concern him.§§ Accordingly, the surgeon should mark out the proposed hairline and other deficient areas that require surgical attention. The most crucial aspect to achieving a natural result with follicular grafting is recreating a natural-appearing hairline. Two anatomic regions should be kept in mind, the central frontal tuft and the respective fronto-temporal recesses. The new hairline should be recreated using the principle of an irregularly asymmetrical insertion of grafts to mimic a natural hairline. As mentioned, a patient’s fronto-temporal recession should be carefully examined and the angle of the fronto-temporal hairline retained to some extent. Advancing the hairline too far forward (usually less than 10 cm from the orbital rim in the central frontal forelock and less than 12 cm from the orbital rim laterally in the fronto-temporal recession) may yield a less natural result and make camouflaging difficult in a younger, rapidly progressive hairline. The textbook paradigm of facial aesthetics dictates that the face ideally should be divided equally into vertical thirds (trichion to glabella, glabella to subnasale, subnasale to menton), but this principle should not apply to hair-restoration surgery. Even if surgery is planned in a younger patient (in his early twenties), the surgeon should consider that this youthful hairline will remain unchanged for the duration of that person’s life and begin to appear unnatural as that individual matures. Furthermore, the geographic region of hair loss that occurs behind the transplanted hair will be more sizable (especially in a younger patient who already requires surgical hair restoration) and may demand a considerable effort to camouflage. The isolated island of transplanted hair in an ocean of naked scalp is a dreadful telltale sign of past success and present failure. One always should be cognizant of the long-term outcome that a transplant will exhibit.

When planning the frontal hairline, the surgeon can rely on the Norwood method as a reliable guide to avoid the creation of an unnatural hairline (Fig. 6-7A-D).13 The construction of the anterior hairline is undertaken by defining three key points: the central, most anterior point of the hairline and the two peaks of the fronto-temporal recession (Fig. 6-7C). The central, anterior point of the hairline should not descend past a level that is situated two finger breadths

above the highest forehead furrow created when the patient gazes upward (Fig. 6-7A). This line is the absolute lowest that is suitable for position of the hairline and only should be used as a starting, reference point. The surgeon then gauges how much higher the hairline should be positioned based on several factors: the patient’s age, fronto-temporal recession, existing hairline, rate of hair loss, and aesthetic opinion. As mentioned, an acceptable starting point for the central forelock is approximately 10 cm from the orbital rim. The lateral two points that define the new peak of the fronto-temporal recession should lie along a vertical axis drawn through the lateral canthus, or slightly medial to this line (Fig. 6-7B). All three points are then connected to form an open oval shape that should appear as a straight line or slightly upward (but never downward) sloping line on lateral view (Fig. 6-7D). Because these guidelines are only meant as a starting point, the hairline should be adjusted to fit the enumerated criteria based on aesthetic judgment.

above the highest forehead furrow created when the patient gazes upward (Fig. 6-7A). This line is the absolute lowest that is suitable for position of the hairline and only should be used as a starting, reference point. The surgeon then gauges how much higher the hairline should be positioned based on several factors: the patient’s age, fronto-temporal recession, existing hairline, rate of hair loss, and aesthetic opinion. As mentioned, an acceptable starting point for the central forelock is approximately 10 cm from the orbital rim. The lateral two points that define the new peak of the fronto-temporal recession should lie along a vertical axis drawn through the lateral canthus, or slightly medial to this line (Fig. 6-7B). All three points are then connected to form an open oval shape that should appear as a straight line or slightly upward (but never downward) sloping line on lateral view (Fig. 6-7D). Because these guidelines are only meant as a starting point, the hairline should be adjusted to fit the enumerated criteria based on aesthetic judgment.

Anesthesia

Intravenous sedation is the preferred method of anesthesia that should be maintained during the initial portion of the procedure; that is, while the local anesthesia is infiltrated and the donor site harvested (Fig. 6-8). The substantial quantity of local anesthesia required for hair transplantation warrants some sedation to minimize discomfort and achieve amnesia. Patients receive a regimen of intravenous midazolam (Versed) sedation, from 4 to 8 mg. Additional medication, usually at an incremental bolus of 2 mg of midazolam, is administered according to patient requirements. The amount of anesthesia needed for sedation is observed to be directly proportional to the patient’s daily or weekly alcohol consumption. Before delivery of intravenous anesthesia, the surgeon may discreetly inquire as to the amount of alcohol that the patient consumes in order to ascertain the necessary amount of anesthetic agent. Generally, this same anesthetic regimen is suitable for all scalp-reduction sessions as well for the first two stages of the Juri-flap procedure. (The reader is referred to the appropriate sections that describe scalp reduction and rotation techniques for detail regarding the proper protocol for anesthesia in those cases.) Further, similar procedures that do not require general anesthesia (e.g., acellular dermis or ePTFE soft-tissue augmentation or chemical peeling) also can employ the same anesthetic technique (Chapters 8 and 9).

Surgical Technique

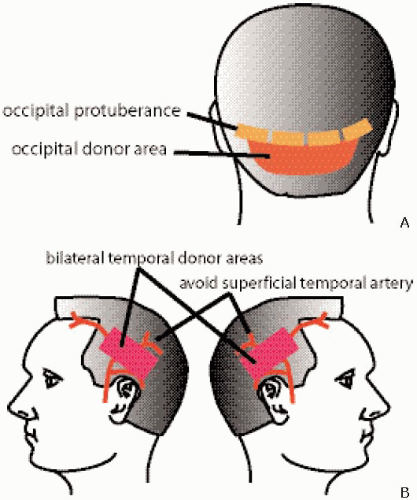

Preparation of the Donor Site

The initial step in follicular-grafting surgery is selection of appropriate donor hair. The surgeon should evaluate the donor site (typically the occipital region) carefully for density, color, and quality of the hair. Generally speaking, the area immediately below the occipital protuberance but still above the inferior border of the hairline is ideal for donor harvesting (Fig. 6-9A). Removing hair above the occipital protuberance predisposes toward harvesting hair genetically programmed for future hair loss; and doing so at the inferior border of the hairline leaves behind a conspicuous scar. The more inferior-based hair (near the occipital hairline) tends to be well suited for placement along the anterior-most hairline as single- or two-hair grafts, because these grafts are finer in nature than the coarser hair situated more superiorly in the occipital region. The surgeon should attentively evaluate the suitability of the hair for this purpose and direct the technicians accordingly to use this hair to dissect one- and two-follicle-sized grafts. If this area does not appear to be

well suited for anterior hairline grafting, the surgeon should entertain the option of harvesting select temporal hair for this purpose (see the following for technique). In addition, the temporal region can serve as an excellent reserve for donor hair when the occipital region has been nearly depleted. When deciding on temporal hair harvesting, the surgeon should be advised to take smaller swaths of hair from targeted areas (e.g., bilateral harvesting of discrete areas) rather than larger passes, which may lead to ultimate asymmetry and tension on closure (Fig. 6-9B).

well suited for anterior hairline grafting, the surgeon should entertain the option of harvesting select temporal hair for this purpose (see the following for technique). In addition, the temporal region can serve as an excellent reserve for donor hair when the occipital region has been nearly depleted. When deciding on temporal hair harvesting, the surgeon should be advised to take smaller swaths of hair from targeted areas (e.g., bilateral harvesting of discrete areas) rather than larger passes, which may lead to ultimate asymmetry and tension on closure (Fig. 6-9B).

FIGURE 6-8. Intravenous sedation with midazolam provides excellent anesthesia during the most sensitive part of the operation, that is, infiltration of local anesthesia and donor-site harvesting. |

After the surgeon has decided on which hair will be harvested, the technician or assistant, who is in charge of preparing the surgical instruments (Fig. 6-10A,B), local anesthesia, tumescent solution, and so on, should shave the occipital or temporal region to prepare the donor site. The amount that the occipital region needs to be shaved depends on the extent of the graft session (small, medium, or large). Although these terms are arbitrary in nature, they serve well to communicate to all surgical team members the number of grafts that will be required; therefore, the number of technicians, operative-time allocation, and extent of the donor site that should be shaved. In addition, the surgeon can establish unambiguous dialog with the patient in regard to the intended surgical effort and thereby set a commensurate surgical fee. For convenience, the authors have used the following guidelines: a small session equals approximately 500 to 700 follicular grafts; a medium-size session, 700 to 1,000; a large, 1,000 to 1,500; and a megasession, more than 1,500 grafts.

Based on the size of the grafting session, the technician should shave the occipital region with an electric razor without a guard (Fig. 6-11). An electric razor is preferred over a straight razor because shearing is less traumatic, faster, easier, and more precise. Also, a short amount of follicular height, or stubble, remains after use of an electric razor that facilitates graft orientation. Wide paper tape can be used above and below the shaved area to hold the untrimmed hair out of the surgeon’s way. The patient should then have an absorbent chuck underpad secured around the neck to avoid soilage of clothing during the operation. The preferred patient position for most of the procedure is sitting upright except during recipient-site creation, at which time a supine position is favored.

Infiltration of Anesthesia and Harvesting of Donor Site

After the appropriate sedation, 1% lidocaine mixed with 1:100,000 epinephrine is infiltrated into the donor (occipital hair) and the recipient sites (fronto-temporal, midscalp, or vertex). Sterile normal saline then is infiltrated into the

subcutaneous plane of the donor site using an 18-gauge needle on a 10-cc syringe for tumescent effect and ease of harvest (Fig. 6-12). The end point of saline infiltration should be when the scalp appears tense and blanched and resistance is met when the plunger of the syringe is depressed. Tumescence yields several distinct advantages: (a) the follicles assume a more perpendicular orientation permitting ease of harvest; (b) the increased tension provides a more stable platform for the incision; (c) the proper plane of dissection (i.e., the subcutaneous plane) is more easily maintained because of hydrodissection and increase in overall depth of the subcutaneous plane; and (d) superior hemostasis is achieved by the added pressure of the saline on the vascular bed.

subcutaneous plane of the donor site using an 18-gauge needle on a 10-cc syringe for tumescent effect and ease of harvest (Fig. 6-12). The end point of saline infiltration should be when the scalp appears tense and blanched and resistance is met when the plunger of the syringe is depressed. Tumescence yields several distinct advantages: (a) the follicles assume a more perpendicular orientation permitting ease of harvest; (b) the increased tension provides a more stable platform for the incision; (c) the proper plane of dissection (i.e., the subcutaneous plane) is more easily maintained because of hydrodissection and increase in overall depth of the subcutaneous plane; and (d) superior hemostasis is achieved by the added pressure of the saline on the vascular bed.

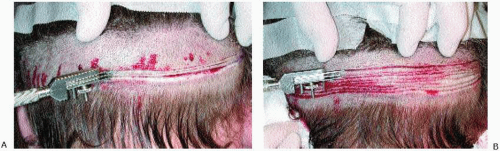

A Tori-style scalpel with 3 No. 10 blades, spaced 2 mm apart, and directed parallel with the hair follicles at 20 to 30 degrees upward is used to harvest two rows of donor hair (Fig. 6-13A,B). Although the tumescent solution tends to straighten the hair follicles somewhat, the overall follicular direction in the occipital region remains downward. During harvesting of the donor site, the surgical assistant should stand in front of the patient to observe for any signs of discomfort (e.g., wincing of the eyes), and should also hold the patient’s head steady, because the patient should be quite heavily sedated during this interval. Usually two rows, each 17 cm long, are sufficient to yield approximately 170 grafts that bear three to six hairs (“minigrafts”) and about twofold to threefold that number of grafts that bear one to two hairs (“micrografts”). (This estimated total of three- to six-hair minigrafts is simply calculated by multiplying 2-mm width minigrafts over a 1-cm distance, which yields five minigrafts. In turn, five grafts  two rows = 10 grafts/cm

two rows = 10 grafts/cm  17 cm = 170 minigrafts in two rows.) Generally, no more than three passes of the Tori scalpel should be undertaken to avoid excessive tension on wound closure.

17 cm = 170 minigrafts in two rows.) Generally, no more than three passes of the Tori scalpel should be undertaken to avoid excessive tension on wound closure.

two rows = 10 grafts/cm

two rows = 10 grafts/cm  17 cm = 170 minigrafts in two rows.) Generally, no more than three passes of the Tori scalpel should be undertaken to avoid excessive tension on wound closure.

17 cm = 170 minigrafts in two rows.) Generally, no more than three passes of the Tori scalpel should be undertaken to avoid excessive tension on wound closure.Of note, several key points should be kept in mind if the temporal region is to be harvested. To reiterate, only smaller patches of temporal hair should be removed from any given site to minimize the chance of asymmetry and wound tension on closure. When dissecting the temporal hair bed, the Tori scalpel also should be directed slightly upward at 20 to 30 degrees (just like in the occipital region) to parallel the direction of the hair follicles. The preferred location for temporal harvesting is several centimeters above the auricle running in an anterior-to-posterior direction. Unlike occipital-based harvesting, the depth of the incision cannot be as indiscriminate because the posterior branch of the superficial temporal artery resides immediately below the hair follicles and may be transected during harvesting (Fig. 6-9B). Therefore, care should be taken to harvest the graft as superficially as possible without violating the base of the hair shaft. Transection of the superficial temporal artery does not have any adverse effect on wound healing but only makes the task of hemostasis an avoidable nuisance.

After all the parallel rows have been dissected with the Tori scalpel, they can then be harvested from the scalp. First, a No. 10 blade is used to taper each collective end of the rows into a fusiform point: The back of the head should resemble the outline of a long football after dissection of all the rows. A tenaculum is affixed to one fusiform end to grasp all the collective rows in its tines, and a No. 10 blade is used to cleave all the rows in the midsubcutaneous plane (Fig. 6-14). The surgeon should carefully observe that the follicular shaft is not being transected during harvesting and that only a small cuff of adipose tissue (about 1 to 2 mm) remains below the hair follicle, because excessive fat below the hair bulb requires additional trimming at the time of graft preparation. The harvested strip grafts then are deposited into a bowl of saline for individual graft dissection and preparation. The donor site is closed with a running, locking 2-0 polypropylene suture that will be removed 2 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 6-15A,B). In the past, surgical staples were used; however, they irritated patients and provided less hemostasis than a locking suture. Of note, any bleeding that appears before wound closure should not be cauterized, because the locking suture will preclude any hematoma or seroma from arising.

Graft Preparation

After the donor site has been harvested, the team of technicians should begin to dissect the individual grafts (Fig. 6-16). Typically, three to four technicians are needed to expedite the dissection process, which can be the most arduous aspect of hair transplantation, followed only by graft insertion for level of technical labor. Graft preparation should be carried out on a large flat surface with good illumination and proper loupe or microscope magnification.

Magnification visors are recommended because they are inexpensive and induce less eyestrain than use of a dissecting microscope. Generally, 2½ times magnification is sufficient for proper inspection of the grafts and reduction of eye fatigue. Flat, tabletop view boxes provide transillumination of the tissue, which facilitates ease of graft dissection. Disposable, Plexiglas sheets should be placed on top of the view box as a cutting board on which the grafts may be dissected without injury to the underlying view box screen. In order to reduce the glare of excessive light from the view box, a surgical drape should cover most of the view box except for the immediate field of dissection.

Magnification visors are recommended because they are inexpensive and induce less eyestrain than use of a dissecting microscope. Generally, 2½ times magnification is sufficient for proper inspection of the grafts and reduction of eye fatigue. Flat, tabletop view boxes provide transillumination of the tissue, which facilitates ease of graft dissection. Disposable, Plexiglas sheets should be placed on top of the view box as a cutting board on which the grafts may be dissected without injury to the underlying view box screen. In order to reduce the glare of excessive light from the view box, a surgical drape should cover most of the view box except for the immediate field of dissection.

All the collected strip grafts should be bathed in a bowl of sterile saline until time for graft preparation. The saline removes any excess blood that may cling to the grafts and prevent desiccation. Gentle handling of graft material and constant moisture are critical for graft viability. A spray bottle with saline should be kept nearby that can be used to

moisten the grafts periodically during the period of preparation and insertion. After the strip grafts have been properly cleansed, they should be separated from one another at both ends with a No. 10 blade (Fig. 6-17). (The reader is reminded that all of the individual strip grafts are still joined together at both ends after strip graft harvesting.) Any excess adipose tissue (greater than 1 mm) that remains below the base of the hair shafts should be trimmed before further graft dissection.

moisten the grafts periodically during the period of preparation and insertion. After the strip grafts have been properly cleansed, they should be separated from one another at both ends with a No. 10 blade (Fig. 6-17). (The reader is reminded that all of the individual strip grafts are still joined together at both ends after strip graft harvesting.) Any excess adipose tissue (greater than 1 mm) that remains below the base of the hair shafts should be trimmed before further graft dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree