Introduction: Organization of Clinical Examination

The first step is to investigate the patient’s presenting complaint and history in the context of their general medical and vascular history. The physical examination (including Doppler auscultation or rapid duplex ultrasound scan) is performed initially with the patient standing and then in the supine position. The initial assessment allows recognition of primary visible varicose veins and their regions of involvement. Further evaluation is required to quantify functional and esthetic impairment, to assess the risks of possible complications, and to establish a plan for management that will be medically appropriate and acceptable to the patient. The adjunctive utilization of duplex ultrasound (DUS) to formulate this plan is now an essential part of the standard of care.

History

Evaluation of the patient with varicosities begins with a complete clinical history. This should include general medical and surgical information as well as information about vascular disease. Besides the presenting complaint, it is important to document the onset of the venous difficulty and the clinical track of the disease with rapidness of progression noted. Contributory factors as well as ameliorating factors are also recorded. The patient should be questioned about each of the symptoms known to be associated with venous insufficiency; leg heaviness, exercise intolerance, pain or tenderness along the course of a vein, pruritus, ‘restless’ legs, night cramps, edema and paresthesias.

Presenting Complaint

Patients may consult the dermatologic surgeon because of symptoms or esthetic concerns, advice on the medical implications of varicose veins or merely be in search of nonsurgical methods of treatment. Some visits are prompted by complications such as the rupture of a varicose vein with bleeding or the recent development of dermatitis, thrombophlebitis, cellulitis or ulceration. Treatment that does not properly address the patient’s primary concerns will not result in a satisfactory overall outcome. Patients also need to have a thorough understanding that long hours of standing without external compression support will hasten the formation of new veins.

General History

The following categories of information regarding general medical history should be obtained for each patient:

- •

Sex, age, weight, and height

- •

Medical history, including hypertension, diabetes, allergy history, tobacco consumption, rheumatological history and general disease

- •

Surgical history, including any fractures or surgical operations

- •

Gynecological and obstetric history, including the number of pregnancies and miscarriages, plan for future pregnancies ( ), duration, dosage, and effect on venous complaints of hormone replacement therapy or oral contraception, and any variation of symptoms with the menstrual cycle.

History of Vascular Disease

A more detailed history of pre-existing vascular disease, including venous and arterial disease, and prior vascular events, should also be recorded, including:

- •

History of venous insufficiency, including the date of onset of visible abnormal vessels and the date of onset of any symptoms

- •

Presence or absence of predisposing factors such as heredity, trauma to the legs, occupational prolonged standing or sports participation

- •

History of edema, including the date of onset, predisposing factors, site, intensity, hardness and modification after a night’s rest

- •

History of any prior evaluation of or treatment for venous disease, including medications, injections, surgery or compression

- •

History of superficial or deep thrombophlebitis, including the date of onset, site, predisposing factors and sequelae

- •

History of any other vascular disease, including peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, lymphedema or lymphangitis

- •

Family history of vascular disease of any type.

Active Symptoms

Symptoms of venous disease are most often located on the medial aspect of the leg. Symptoms often are increased by heat, prolonged standing, or during the menstrual period in women in whom progesterone is predominant. Venous symptoms are typically relieved by cold, ambulation, rest with leg elevation, or wearing of gradient elastic stockings ( ).

Characteristics of venous pain include a dull ache, burning or pruritis. This pain may be localized to a protruding varicose or reticular vein. It is rarely described as a sharp stabbing pain or pain radiating down the back of the thigh. Surprisingly, nighttime muscle cramping is caused by venous insufficiency as many patients relate that the cramping is eliminated when varicose veins are treated by endovenous techniques. Restless legs may rarely be caused by venous insufficiency. The extent and origin of venous disease and pain are listed in Box 3.1 .

- •

50% of females

- •

20% of males

- •

Many women deprive themselves of outdoor activity

- •

More than cosmetic for many

- •

Leads to aching, fatigue, redness, itching, swelling and ulceration

- •

Overwhelmingly under-diagnosed cause of leg pain in women

Physical Examination

Findings of special importance on physical examination are listed in Box 3.2 . Some of these physical findings may help to guide the choice of treatment modality and its degree of difficulty. Ambulatory phlebectomy of such thick-walled veins is time consuming and tedious but effective as this type of vein is resistant to sclerotherapy. Endovenous techniques with the new small fiberoptic delivery systems can rarely be used as an option for this situation.

- •

Asymmetry of limbs

- •

Size, length and ankle diameter

- •

Scars

- •

Previous venous surgery

- •

Previous venous ulcers

- •

Cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency

- •

Superficial vascular malformations such as port wine stains

- •

Muscular tone and development

- •

Hypertrophy of veins and thickening of vein walls

Clinical evaluation of the patient with venous disease remains the foundation on which both the diagnostic and therapeutic steps are built. The presenting complaint and the patient’s goals for treatment must be defined and clearly understood. Knowledge of the patient’s medical, social, work and family environment is important. A general assessment of the patient’s venous disease, including its severity and consequences, is critical to judging the risks of complications, both vascular (superficial venous thrombosis, prehemorrhagic bulla, ulceration) and trophic (leg ulcer).

For example, swelling may result from acute venous obstruction (such as is seen in deep vein thrombosis [DVT]), or from deep or superficial venous reflux, or other nonvenous causes. Hepatic insufficiency, renal failure, cardiac decompensation, infection, trauma and environmental effects can all produce lower extremity pitting edema that may be indistinguishable from the edema of venous obstruction or venous insufficiency. Edema due to lymphatic system malfunction may be due to primary obstruction of lymphatic outflow.

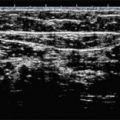

Rather than being considered a special diagnostic modality, the use of Doppler for auscultation was considered an integral part of the clinical examination of patients with venous disease ( ) but is now being replaced by portable solid state duplex ultrasound (DUS). While Doppler is equivalent to the stethoscope in a routine physical examination, DUS is equivalent to an echocardiogram but is so convenient that hand-held Doppler may be bypassed. Hand-held Doppler and DUS helps to confirm the clinical findings of the physical examination, and is particularly valuable because it can reveal relevant subsurface reflux in portions of the great saphenous vein which cannot be visualized. Doppler or DUS helps define the topography of varicose disease and the hemodynamic status of the deep venous system. Repeated examinations over time help to document the results of treatment or the natural course of the disease.

Equipment

The clinical examination requires a medical file, an examination platform, excellent lighting, a phlebological examination table, a continuous-wave Doppler apparatus or a portable DUS machine, and a small amount of miscellaneous equipment. The use of DUS is covered in Chapter 4 .

•

Examination platform

Having the patient stand on a platform consisting of two or three steps will greatly increase the physical comfort for the physician and allow a more complete examination. While on a platform, In this way the patient can be examined in a standing position without requiring the physician to contort their body or cause undue neck extension.

•

Lighting

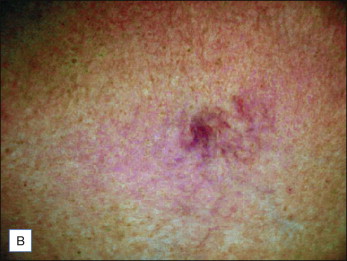

Lighting should be even and consistent. The simplest approach is to have a 75 W lamp on each side of the patient. Uniform overhead fluorescent lighting is satisfactory. Hot spots from strong halogen lamps will bleach out smaller blue reticular veins and is not recommended. Some useful devices to examine smaller telangiectasias without surface reflection of light are several cross-polarized visualization systems manufactured by Syris Scientific (LLC, Grey, MA). The visual enhancement of fine telangiectasia and hard-to-see reticular veins is seen in Figure 3.1 . Transillumination using LED or halogen light sources (see www.veinlite.com ) may be helpful to map out reticular veins within 1–2 mm of the skin surface ( Fig. 3.2 ).