Newborn Skin Conditions

Khanh P. Thieu

The newborn skin is target to a host of cutaneous conditions that, thankfully, are often benign and self-limiting. However, common neonatal skin conditions can be a source of significant consternation for first-time families due to lack of recognition and awareness. Understanding the clinical presentation and course of common skin diseases will help clinicians reassure parents, institute appropriate therapy as needed, and avoid unwarranted workup and treatment of presumed serious diseases. This chapter is designed to provide a succinct discussion of the most common skin conditions affecting neonates. While the conditions discussed below are generally benign and usually merit only nominal interventions, clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referrals when the diagnosis is uncertain or when lesions do not resolve as expected with appropriate therapy. A summary of these conditions is presented in Table 19-1.

Diaper Dermatitis

|

A 10-month-old female infant presents to the pediatric clinic for evaluation of a rash in her inguinal region. Her mother relates that she recently hired a new nanny and feels that the baby’s diaper has not been changed as regularly as before. On physical exam, erythematous, confluent areas of shiny erythema over labia majora and buttocks is noted (Fig. 19-1). The inguinal folds are relatively spared. The mother is concerned that this may represent a fungal infection.

Background

Diaper dermatitis entails all cutaneous eruptions in areas covered by the diaper. Prototypically, diaper dermatitis refers to conditions that are caused or exacerbated by the wearing of diapers, but it can also include skin diseases that have a predilection for the diaper area whether or not diapers are worn. The term will be used in this chapter to refer to the two most commonly encountered form of diaper dermatitis: irritant diaper dermatitis and candidiasis.

Diaper dermatitis is seen commonly in infants, with peak incidence occurring between 6 and 12 months. Boys and girls are affected equally. The condition is prevalent and can be seen in up to 50% of infants in mild forms. Diaper dermatitis is not limited to infants and can affect anyone who wears a diaper, especially elderly patients.

Key Features

Diaper dermatitis is a cutaneous eruption in the diaper area arising usually in setting of prolonged contact with urine and feces ± Candida albicans infection.

Skin findings.

Irritant diaper dermatitis: erythema and scaling on the convex surfaces of diaper area with sparing of inguinal folds.

Candidal diaper dermatitis: diffuse erythema in the perineal area, or coalescing small pink papules topped with scale.

Treatment: frequent diaper change, bland emollients, topical steroids (irritant diaper dermatitis), topical antifungals (candidal diaper dermatitis).

Clinical course: most cases generally resolve within 1 to 2 weeks.

Pathogenesis

The etiology of diaper dermatitis is multifactorial. Wetness from urine and occlusion with diapers causes the skin to be overhydrated, making it more susceptible to friction and maceration. Prolonged contact with urine and feces

further damages the epidermis due to activity of fecal proteases and lipases and contamination from bacteria. Frequent diarrhea and antibiotic use have been shown to be independent risk factors. Last, Candida albicans is believed to play a major role in diaper dermatitis and has been isolated from the perineum in up to 90% of children with diaper dermatitis. The warmth and moistness provided by diapers make the perineum particularly hospitable for Candida, and some infants lack the developed immune systems needed to ward off candidal infections. About 3% of infants develop candidiasis in the diaper area from the 2nd to 4th month of life.

further damages the epidermis due to activity of fecal proteases and lipases and contamination from bacteria. Frequent diarrhea and antibiotic use have been shown to be independent risk factors. Last, Candida albicans is believed to play a major role in diaper dermatitis and has been isolated from the perineum in up to 90% of children with diaper dermatitis. The warmth and moistness provided by diapers make the perineum particularly hospitable for Candida, and some infants lack the developed immune systems needed to ward off candidal infections. About 3% of infants develop candidiasis in the diaper area from the 2nd to 4th month of life.

Table 19-1 Summary of Common Newborn Skin Conditions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 19-1 Primary irritant diaper dermatitis. Confluent areas of shiny erythema over labia majora and buttocks (Courtesy of Jan E. Drutz, MD). |

Clinical Presentation

Irritant Diaper Dermatitis

The initial eruption consists of erythema and scaling on the convex surface of the lower abdomen, inner thigh, and buttock area (Fig. 19-1). The genitocrural creases are typically spared. Fissures, erosions, bullae, and vesicles can sometimes be seen in the involved areas. Symptoms can range from relatively asymptomatic presentation to striking discomfort from soreness and inflammation, especially following bowel movements or urination.

Candida Diaper Dermatitis

Candidiasis in the diaper area can present with either diffuse erythema in the perineal area (including creases) with peripheral scaling and satellite pustules, or coalescing small pink papules, topped with scales, in the perineal area (Fig. 19-2). Unlike in irritant diaper dermatitis, the inguinal folds are usually involved.

Diagnosis

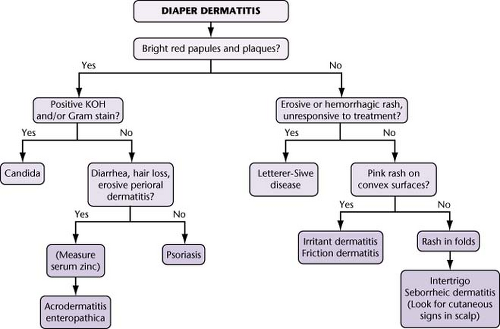

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history, appearance, and location. Candidal diaper dermatitis can be confirmed with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, although this is usually not necessary. An algorithm for diagnosis of diaper area dermatitis is presented in Figure 19-3.

Differential Diagnosis

Diaper dermatitis can be confused with atopic dermatitis, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and psoriasis. Atopic dermatitis tends to be pruritic and is associated with other rashes in the typical atopic distribution: face and extensor limb surfaces. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder characterized by marked perioral dermatitis, diarrhea, hair loss, and failure to thrive, in addition to the diaper-area rash. Psoriasis typically also demonstrates involvement outside of the diaper area, including scalp and nails.

Treatment

Irritant Diaper Dermatitis

Prevention of exacerbating factors is the key to successful treatment. The goal is to restore the skin’s barrier function and keep the area dry. Key factors are outlined below:

Rash does not improve with above treatment.

If the patient has history of rashes outside the diaper area, which may indicate an alternative diagnosis.

Diaper change: Frequent diaper changes and gentle cleansing of the diaper area with each change will minimize the skin’s contact with feces and urine. Cleaning is best achieved with lukewarm water, followed by a gentle but complete drying of the area. Harsh brushing should be avoided.

Emollients: Bland emollients are the first-line topical therapy. Topical zinc oxide or petrolatum helps provide a barrier against urine and feces. Apply emollients frequently and especially after bathing.

Corticosteroids: Moderate or severe cases may benefit from a low-potency topical steroid (e.g., hydrocortisone 1%). The steroid may be applied three times a day, covered by emollients to improve absorption. Strong corticosteroids or extended duration of steroid use beyond several days should be avoided to prevent skin atrophy and striae.

For dermatitis lasting more than a week, consider candidal infection.

While unlikely other than in cases of abuse, secondary infection such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) should be considered with appropriate morphology.

If there is diarrhea, hair loss, and periorificial dermatitis, consider checking a zinc level to rule out acrodermatitis enteropathica.

Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

Treatment consists of minimizing moisture to the diaper area by frequent diaper changes and use of emollients as outlined above. In addition, topical antifungal agents such as nystatin or ketoconazole two to three times daily are effective and typically lead to resolution by 2 weeks. If inflammation is significant, consider adding a short course of topical hydrocortisone 1% to reduce skin inflammation.

“At a Glance” Treatment

Irritant diaper dermatitis:

Frequent diaper changes and gentle cleansing

Bland emollients are the first-line topical therapy. Topical zinc oxide or petrolatum helps provide a barrier against urine and feces. Apply emollients frequently and especially after bathing.

Moderate or severe cases may benefit from a low-potency topical steroid (e.g., hydrocortisone 1% TID PRN). Strong corticosteroids or extended duration of steroid use beyond several days should be avoided to prevent skin atrophy and striae.

Candidal diaper dermatitis:

Minimize moisture by frequent diaper changes.

Emollients

Nystatin cream or ketoconazole cream BID–TID for 2 weeks

If inflammation is significant, consider adding a short course of topical hydrocortisone 1% to reduce skin inflammation.

Clinical Course and Complications

Irritant diaper dermatitis generally resolves within several days after initiating treatment. Candidal diaper dermatitis follows a more protracted course but usually resolves within 1 to 2 weeks. Complications most frequently arise from secondary bacterial superinfections, in which case an appropriate topical antibiotic may be added to the skin care regimen.

ICD9 Codes

| 692.9 | Contact dermatitis and other eczema, unspecified cause |

| 112.3 | Candidiasis of skin and nails |

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum (ETN)

|

A first-time mother brings in her 10-day old baby boy to the pediatric clinic for evaluation of a rash on the baby’s back. The rash started on the back 6 days after the baby was born, and crops of lesions have appeared and disappeared over the past several days. On physical examination, scattered discrete pustules and papules, with surrounding erythema are seen on the baby’s back (Fig. 19-4). The mother is concerned that this may represent some kind of infection, although her baby has not exhibited any concerning symptoms.

Background

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) is a common, benign, self-limited cutaneous eruption affecting healthy newborns. The condition’s prevalence is positively correlated with birth weight and gestational age, and thus, is rarely seen in significantly premature infants. ETN is present in approximately 30% to 70% of full-term newborns and affects different sexes and races equally.

Pathogenesis

The underlying pathogenesis of ETN remains unknown. Although the lesions

characteristically contain an eosinophilic infiltrate, an allergic or hypersensitivity-related etiology has not been confirmed.

characteristically contain an eosinophilic infiltrate, an allergic or hypersensitivity-related etiology has not been confirmed.

Key Features

Pathology: common, benign, self-limited cutaneous eruption of unknown etiology.

Skin findings: scattered, discrete papules and/or pustules surrounded by erythematous wheals.

Treatment: reassurance.

Clinical course: complete resolution typically occurs by first week of life.

Clinical Presentation

Classically, the eruption consists of scattered, small, discrete papules and pustules surrounded by irregular erythematous macules or erythematous wheals measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter (Figs. 19-4 and 19-5). The individual papules and pustules are discrete, although the background areas of erythema may become confluent. The lesions are asymptomatic and can be found anywhere but have a predilection for the face, trunk, and proximal extremities.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on clinical appearance. Microscopic examination of the pustular contents can provide diagnostic confirmation. A Gram stain or Wright stain of the contents will show a predominance of eosinophils. Peripheral eosinophilia is observed in approximately 15% of newborns with ETN.

Differential Diagnosis

Erythema toxicum can be confused with herpes simplex infection, impetigo, or miliaria rubra (heat rash). Herpes simplex lesions tend to have a more vesicular appearance rather than pustular and require a history of herpes from the mother. Impetigo usually has more developed pustular lesions and can be differentiated based on Gram stain of intralesional contents. Presence of neutrophils on Wright stain or presence of organisms on Gram stain is suggestive of bacterial impetigo. Diagnosis of miliaria rubra typically follows from a history of excessive warming, either from occlusive clothing or from an incubator. Lesions are usually more confluent than those seen in ETN and demonstrate a lymphocytic infiltrate on Wright stain.

Figure 19-4 Erythema toxicum neonatorum on the shoulder of a 10-day-old infant.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|