Motor Branch of Masseter for Innervation of Free Muscle Flap

Michael J. A. Klebuc

DEFINITION

The descending branch of the motor nerve to the masseter muscle (CN V) can be selectively divided and employed to innervate free muscle flaps, utilized for smile restoration.

ANATOMY

The masseter nerve branches from the mandibular nerve and passes above the lateral pterygoid muscle where it runs through the mandibular notch to enter the substance of the masseter muscle.

Along its intramuscular path, the main trunk liberates a series of small proximal branches and terminates in a long descending branch that courses obliquely in posteroanterior, proximal-distal trajectory.

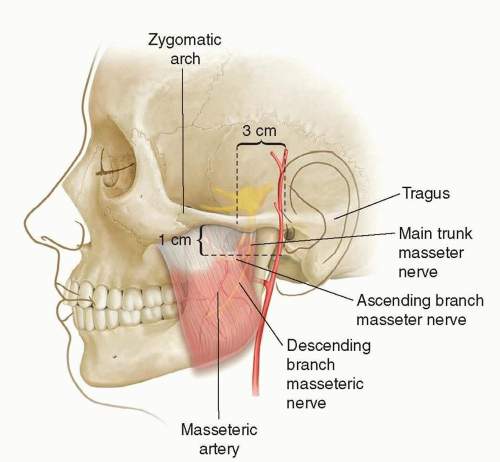

The main trunk of the masseter nerve can be identified at a point 3 cm in front of the tragus, 1 cm below the zygomatic arch, and 1.5 cm deep to the SMAS (FIG 1).1

The masseter muscle has three lobes (superficial, middle, and deep).

The motor nerve to the masseter (CN V) lies on the superficial surface of the deep lobe.2

The main trunk and descending branches contain approximately 2700 and 1550 myelinated motor fibers, respectively.1,3

The descending branch of the masseter nerve is usually selectively transected and employed to innervate free muscle flaps utilized for facial reanimation.

PATHOGENESIS

The masseter nerve is frequently selected as a source of innervation in cases of bilateral facial paralysis and when the facial nerve is unavailable as a donor (ie, Moebius syndrome, Lyme disease, bilateral temporal bone fractures, brainstem cavernous malformation, Guillain-Barré).4

Often selected over cross face nerve grafts in older patients where the potential for nerve regeneration is diminished.5

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Etiology of the facial paralysis:

Developmental

Traumatic

Post-tumor extirpation

Bell palsy

Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Patient age:

Peripheral nerve regeneration declines with advanced age.

There is no definitive age cutoff for cross face nerve grafting; however, after the age of 50 to 55 years, the ipsilateral motor nerve branch to masseter or other adjacent cranial nerves often provide a more reliable source of innervation to free muscle flaps with more powerful muscle flap contraction.

Comorbidities impairing nerve regeneration:

Smoking—higher risk of skin flap necrosis

Diabetes

Vascular disease

Previous radiation

Neurologic disorders

History of hypercoagulable state:

Patient or family history of pulmonary emboli or deep venous thrombosis signals the need for a hematologic workup prior to free, functional muscle flap reconstruction.

The patient’s level of motivation and willingness to comply with postoperative physical therapy is also important to ascertain.

History of temporomandibular joint dysfunction—consider alternative technique.

Physical Examination

Active, forceful, contraction of the masseter and temporalis muscles is confirmed by palpation.

The face is examined for previous access incisions and signs of trauma or injury to the muscles of facial expression.

Dental occlusion and mouth opening are evaluated to rule out temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

A cranial nerve examination is performed to identify additional neurologic deficits.

Palpate and Doppler the superficial temporal and facial artery and veins on the paralyzed hemiface to verify patency.

IMAGING

Imaging studies are seldom required in the presence of a normal physical examination.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Smoking cessation and avoidance of nicotine

Discontinuation of oral anticoagulants

EMG

Concomitant activation of the masseter muscle with attempted smiling (may predict development of an effortless smile)6

Mark the nasolabial folds and smile vectors prior to entering the operating room.

Positioning

Supine on the operating table with arms tucked

Narrow head extension with foam- or gel-filled headrest.

Nasotracheal intubation with nasal ray endotracheal tube sutured to the columella and supported on the hair-bearing scalp with foam, silk tape, and staples (FIG 2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree